It's time for a U23 women's category at the UCI Road World Championships

Glaring omission leads to drop-outs and lost opportunities, highlights the need for a stepping stone to the elite ranks

National federations will descend onto the historical cycling region of Flanders in Belgium for the 2021 UCI Road World Championships, held between September 19-26. Every team will bring the best athletes from their country to compete for the 11 world titles available across the time trials and road races, with junior and elite categories for the women and men, a mixed relay, plus an under-23 men's category.

There will, however, be a glaring omission from the event schedule; once again there is no under-23 women's category.

Mountain biking and cyclo-cross are paving the way for their young female athletes with an under-23 women's category. However, road racing remains the only discipline that has not created a stepping stone for riders exiting the junior ranks at age 18. The majority of these young riders are left to either sink or swim after jumping into the deep end of the elite women's peloton.

Cyclingnews has reached out to the sport's governing body every year for the past three years ahead of its flagship World Championships to ask why there are no specified road race and time trial categories, world titles, or gold medals available for under-23 women. Why hasn't an under-23 racing calendar been created for this group, as it has for their male peers?

The UCI has not responded.

In a wide-ranging feature, Cyclingnews examines the importance of adding an under-23 women's category at the Road World Championships and the need to create a bridge for younger riders to develop during their formative years between racing ages 19-22 so that they are prepared to join the elite peloton.

We also consider how excluding this category for women from the World Championships and Nations Cup can result in a loss of visibility, reducing the potential for funding, contracts, development and opportunity, and how it can lead to athletes quitting the sport. It’s also an example of the sort of blatant inequalities that women, for generations, have pushed to overcome in the sport of cycling.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"There should be an under-23 women’s category at the World Championships, and an under-23 Nations Cup calendar," double World Champion Anna van der Breggen told Cyclingnews.

"It might be a big change and it might be hard to organise, but if it’s too difficult for most of the girls to go straight into elite women’s cycling, they quit. That is the big problem at the moment in women’s cycling; the level is too high for the riders coming out of the juniors, and when they get to be 21, 22 or 23 years old, they might have left the sport already. It’s not that they were not talented enough to be good riders but the step to get there has become too big."

The young rider cohort

Limited field sizes in women racing, and possible heightened financial requirements, have often been suggested as the reasons for not adding an under-23 women's category to the UCI Road World Championships.

"The quick answer is that I don't know why there isn't an under-23 women's category at the Worlds, but the only people that would know would be the UCI," said Bob Varney, co-team director of Drops-LeCol, a long-running and successful British Continental team.

"To second guess them, I would say that it's due to financial resources because it would mean additional people at the race and accommodations. Perhaps, they might also say that there are not enough riders to go around to make a fair peloton.

"I think it's all humbug, and they need to do it and address it immediately. I think it's unfair. If you ask any of the under-23 riders, they would all love to have a World Championship."

A closer look at the current UCI Women's Road World Ranking [as of September 2021 - ed.] reveals that of the 1,128 athletes who score points on the international calendar, 384 female athletes are between the racing ages of 19-22.

This under-23 cohort is the largest age group in the rankings, and that is compared to 250 female riders between the ages of 23-26, and 184 female riders between the ages of 27-30, and 146 riders aged 31-34, and 74 riders aged 35-38.

| Cohort | Ranked riders | Total points | >100 points | % >100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Junior | 8 | 255.00 | 0 | 0% |

| U23 | 384 | 17,991.73 | 35 | 9.11% |

| 23-26 | 250 | 24,730.90 | 49 | 19.60% |

| 27-30 | 184 | 26,891.00 | 48 | 26.09% |

| 31-34 | 146 | 24,510.33 | 36 | 24.66% |

| 35-38 | 74 | 6,802.00 | 12 | 16.22% |

| 39-42 | 36 | 6,420.00 | 7 | 19.44% |

| 43-46 | 25 | 1,230.00 | 4 | 16.00% |

| 47-50 | 14 | 252.00 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 50+ | 4 | 50.00 | 0 | 0.00% |

However, the under-23 age cohort (19-22) also has the lowest proportion of riders scoring greater than 100 points – 35 of these riders have scored over 100 points – which is only 9.11 per cent of the group. Riders like Emma Norsgaard and Lorena Wiebes are the highest point scorers of this under-23 group, scoring 1,679 and 1,246 points respectively.

The majority of this youngest and largest group of competing riders are also the least developed and, with no under-23 category, have the least opportunity to progress to the next level.

The 2021 Women UCI Points Scorers graph below, created by Cyclingnews' Laura Weislo and based of off the UCI World Rankings, shows that the average points scored for under-23s is 46, compared with 99 points for athletes aged 23-26, 146 points for those aged 27-30, and with the highest average point scorers at 168 for the 31-34 group and 178 for the 39-42, largely thanks to riders like World Ranking leader Annemiek van Vleuten, who has a whopping total of 4,800 points as of September 3.

The 384 riders aged 19-22, however, would be enough to make up a healthy field size for a separate under-23 women's category at the World Championships, which would allow this group to race against their peers at the same level of development.

"At that age, it is especially challenging to get into the sport. Men have an under-23 category, and teams have separate development programmes to help those riders make the step up to a professional career," Van der Breggen said.

"It's so much harder for junior women to step into the elite ranks and race with us. They often don't get to race as much, and they jump into our field straight away. That is something that isn't good in women's cycling."

The UEC Road European Championships, as an example, is an event that hosts an under-23 women's category with healthy field sizes for the road race that has averaged roughly 80 athletes in the last five editions.

"It's nice to have an event for the under-23 women at the European Championships because it's a nice way for them to get a result and to be the best of their own age group," said Loes Gunnewijk, the women's road coach at the Dutch National Team.

Many athletes are available to create an under-23 women's category at road Worlds and for a corresponding calendar of events. It also takes time for junior riders to develop enough to move into the next age group cohort of top-performing athletes (points scorers). However, when forced to make the jump too soon, a significant number of riders, for a variety of reasons, drop out of the sport before reaching their maximum potential.

Time to top-5

The protégées in women's cycling excel directly out of the junior ranks into elite-level competition. We think of athletes like Marianne Vos, who won her first elite road race world title at age 19. There are stand-out performers currently competing at the highest level, such as Lorena Wiebes (22), Emma Norsgaard (22), Niamh Fisher-Black (21), Evita Muzic (22), Kata Blanka Vas (20) and Sarah Gigante (20), to name a few.

The reality for most young riders, however, is that they need five years to develop toward being competitive among elite competition from the time of exiting the junior ranks, or for late-comers, from the time of entrance into the sport.

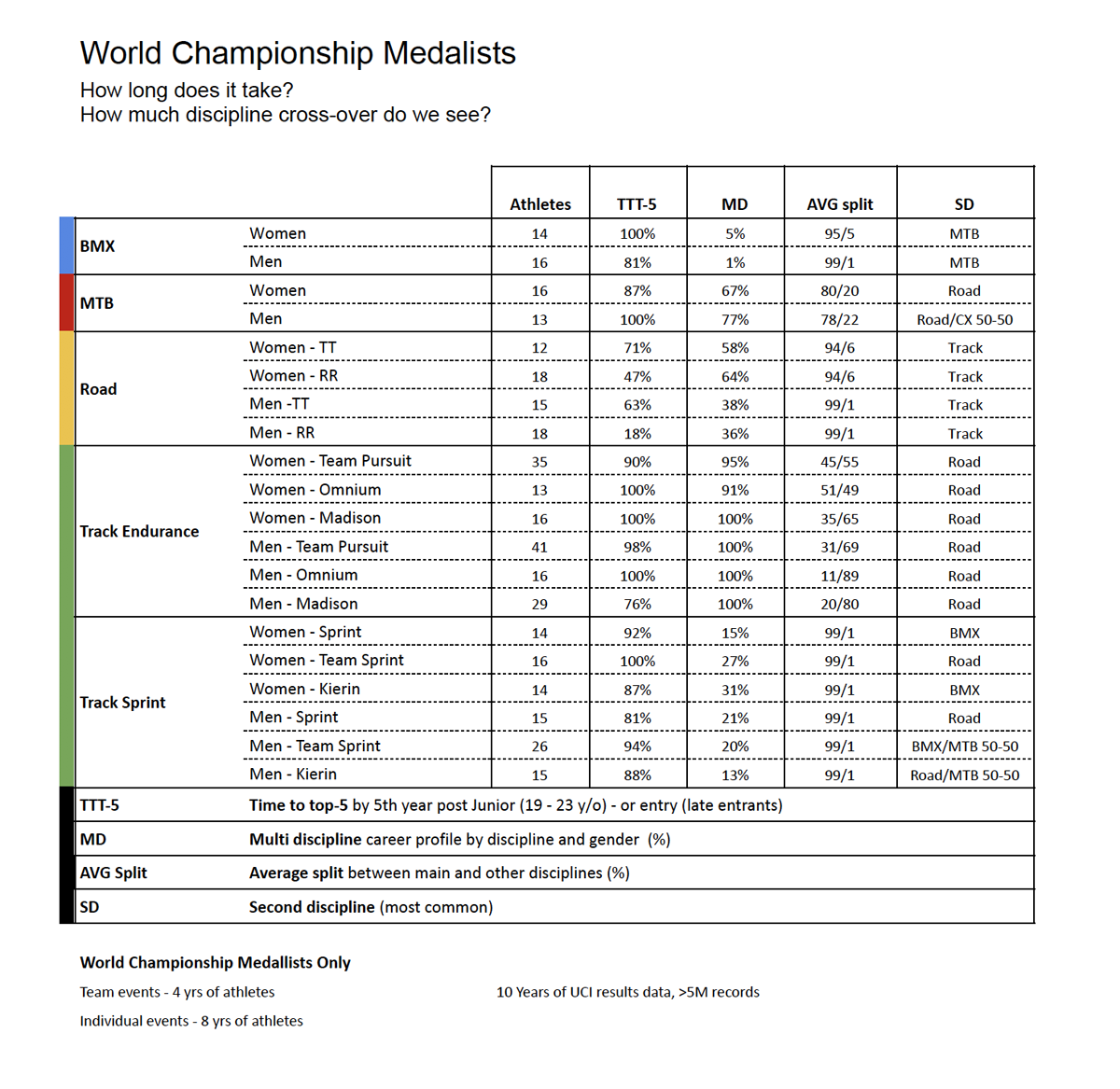

Cycling Canada has worked with Canadian Tire Data Science to develop an internal metric – a cohort analysis using the Glicko rating system. Initially intended for the primary use as a chess rating system, it looks at, for the best cyclists in the world, how many get within one standard deviation of global top-five within five years from exiting the juniors or from entry into the international competition – a rating they called 'Time to top 5' (TTT-5).

"We look at all the medallists of the UCI World Championships, and significant competitions, over the last eight years for individual events and four years for team events. We look back to when these athletes were juniors to see their performances through to elites over those years," said Kevin Field, former head of performance at Cycling Canada and sports director of North American teams Symmetrics, Livestrong, Optum, and SpiderTech.

"In women's road racing, we looked at the 18 medallists, and in women's time trials, there were 12 medallists over the last eight editions of the UCI Road World Championships. We were able to look back at their performance history through the last ten years across five million records of results and data to see what was their progression curve, in terms of results and performance, and when they got to within one standard deviation of the top 5."

The metric analysis revealed that, in the women's time trial, of the 12 medallists, 71 per cent of them get to the top 5 within five years of being a junior or five years from entering into international races. In women's road racing, of the 18 medallists, only 47 per cent of them get to the top 5 within five years of being a junior or entering international competition.

"That tells us that to become a World Championship medallist in women's road; you need more than five years to develop from the time you enter the elite international competition. For the rest, it takes longer," Field told Cyclingnews.

"In addition, in men's road racing, of the 18 medallists, only 18 per cent of them get to the top 5 cohort within five years of exiting junior or entry into the sport, and for the rest, it takes longer."

It might take a long time for male riders to reach the top five after exiting the junior ranks, but the sport offers them opportunities to develop through their under-23 years with a robust three-tier team system, a separate category of Nations Cups and other international races such as the Tour de l'Avenir, Baby Giro, and Il Piccolo Lombardia.

Young male riders are given an extra four years to develop among their peer group while also having opportunities to mix in with the elite peloton. The development plan for male cyclists allows them to experience a four-year bridge that is not available to under-23 women.

In most cases, the under-23 women are grouped together with the elite women and they all race together in the two-tier teams system, WorldTeam and Continental, although some teams are dedicated to developing young riders such as Parkhotel Valkenburg, NXTG Racing, and Canyon-SRAM is set to for a development team next year. Twenty24 Pro Cycling is no longer a Continental team but has been a development programme for young riders in the US for over a decade.

There is often a separate young riders classification within races. For example, there is a youth category for the Women’s WorldTour currently led by Niamh Fisher-Black of SD Worx.

There are currently separate under-23 Nations Cup calendars in place for junior men and women, and under-23 men. This year, there was an under-23 women’s stage race Watersley Womens Challenge classed as a UCI 2.2-level event, held from September 3-5 in the Netherlands. It had a field of 76 riders and was won by Marit Raaijmakers from Parkhotel Valkenburg.

"Road athletes, whether they are men or women, take longer to develop into top international competitors than in any other discipline," Field said. "If you look at all the other disciplines, particularly mountain biking, the time to top 5 is 100 per cent, and that discipline has a robust under-23 development pathway.

"Having the opportunity to succeed is so important and keeping young riders engaged and motivated to move forward and the under-23 category is critical to that development, and we’ve seen that in the under-23 men’s category and we see it in other disciplines like mountain biking.

"It’s four years that we have to work with athletes to develop them and catch them up to their elite international peers, and if we do it well, we can get them there. They come out of juniors under trained and under exposed to racing relative to their elite peers and relative to other countries, and if we can be smart and deliberate with the under-23 years, we can get these athletes up to that highest level.

"Currently, this is not in place for the women and so it can be tough because motivation goes down, it’s hard to keep athletes engaged, there are less opportunities with teams and races, and it can be very difficult."

Drop-outs

Many female athletes often excel through the junior ranks but leave the sport during their first years in the elite levels while at the age of 19-22. The UCI World Ranking reveals that the number of young riders currently competing is more than the older age groups, indicating an elevated drop-out rate as female riders progress through the sport.

"You have to ask why? We would expect that the biggest age group would be the middle tier of 24-31, but it's not. That is where we could speculate that we are getting too many young riders dropping out," Field said.

"If we use common sense to theorize; it's harder to keep women involved in sport, and here we have a sport [cycling] that is really hard to begin with, and we make it even harder on this particular group [under-23 women] by not giving them a dedicated age category where they can blend and mix with elite peers while still racing within their age group, which would keep them motivated, developing, moving forward and progressing."

Dutch rider Rozemarjin Ammerlaan, 21, won the junior women's time trial world title at the Road World Championships in 2018, but she hasn't made the selection to compete with her nation in the elite category for the last three years.

Similarly, Megan Jastrab, 19, the junior world champion in 2019, did not make USA Cycling's selection for the elite women's races at Worlds this year. 2017 junior world champion Elena Pirrone (Italy) hasn't made her team for Worlds since her 2018 appearance.

Ammerlaan is currently enrolled in a mechanical engineering undergraduate programme and races for the development team NXTG Racing. She said that upon leaving the junior ranks, there was no place for her, or other under-23 riders like her, among the elite team that competes at the World Championships.

The Dutch team will field eight riders at the World Championships in Flanders this month to include Van der Breggen, Van Vleuten, Chantal van den Broek-Blaak, Lucinda Brand, Ellen van Dijk, Amy Pieters, Demi Vollering and Vos.

"We have a lot of competition in the Netherlands; for example, there are some 60 riders who would start at our National Championships, and that doesn't happen in many other countries. Many of the riders who compete in the elite races from our country at the World Championships are a lot older than I am and a lot stronger," Ammerlaan told Cyclingnews.

Ammerlaan said that if there were an under-23 women's category at the World Championships, she likely would have had an opportunity to race for another world title across three additional World Championships.

"Yes, I would have had a great chance to be there if I were in good shape and if there was an under-23 event. We have a strong group of under-23 riders, but we can't show it because there's no category for us. Some of the young riders are on top [trade] teams, but they are learning and helping their more experienced teammates. If there was an under-23 category, these riders could show their potential," Ammerlaan said.

"It would also bring us exposure, for sure. It would give us a chance to show that we can race, not just hang on like racing in the elite field. When you are a junior, you race against one another, but as an under-23 rider, you have to hang on and be happy with 60th place with the elites. If there were an under-23 category at the Worlds, we could show what we are capable of in our age category. It might help to get a contract or to show what you can do in a race."

A vision

The World Championships is only one race, but it's the biggest race globally, and the sport governing body could be leading the way when it comes to providing a pathway for under-23 women, in the same way it does for the under-23 men in the sport.

Now more than ever, particularly given the sharp progress and professionalism of women's cycling since it implemented the Women's WorldTour in 2016 and a two-tier – WorldTeams and Continental Teams – system last January. The new reforms have led to the introduction of the minimum salary for riders contracted with top-tier teams. No longer do these women need to work a second job while trying to progress in cycling. They can train and race full-time, teams are becoming more professional, and more and bigger races are on the way, such as the women's Tour de France in 2022.

There's been a noticeable increase in the overall strength of the women's peloton over the last two seasons, but for junior women, it means an even bigger gap to jump across to get to the elites.

"We are at a point now where having an under-23 category at Worlds is a good step. It's taken a little while to get to that point where there's the depth in the peloton to support it. There is enough depth and enough women to fill both categories now," former world champion Lizzie Deignan told Cyclingnews.

"There's been a lot of growth in women's cycling, so much so that the jump from juniors to elites is quite dramatic. It's different than it used to be when I was racing when I was younger. There needs to be a close look at redesigning the calendar. We get so many more new races, which is brilliant, but there needs to be a stepping stone in the middle for the younger riders."

Iris Slappendel, co-founder of The Cyclists' Alliance, believes that, while an under-23 women's category at the World Championships is essential, it's equally as crucial that the sport's governing body and stakeholders create a sustainable vision for the development pathway for female riders exiting the junior ranks so that they can successfully bridge the four-year gap to elite competition.

"It should be part of a bigger plan. Adding only an under-23 category at the Worlds isn't as valuable as adding a calendar as well. We see some first and second-year riders doing well. Still, for the development of women's cycling for the majority, it would be valuable to create a category held alongside the men's under-23 Nations Cup and some stage races. There could be a series of racing where riders can show themselves at an equal level," Slappendel told Cyclingnews.

"It's a decisive time in a young rider's life because they are developing in their personal lives, studies, and making a lot of choices for a career. It's a crucial time for women between the ages of 16 and 22 that requires motivation, gaining international experience, and a lot of young riders find it hard to show themselves among the elite fields."

Field argued that with the professionalism and progress happening in women's cycling, creating a calendar for under-23 women and a World Championship would, in turn, help the recruitment process for riders entering the higher tiers of the sport.

"There is great progress happening on the Women's WorldTour with more stability and longer-term contracts, and gaining the security and provisions that the men have had in place for years, which is great. For the younger riders that get into the top teams, it's great for them, but it creates pressure for the bigger wave of young riders who are just below that tier, which is the majority," Field said.

"Road has the highest depth of field [internationally ranked athletes] compared to the other disciplines. It is the most professionalised discipline. It has the most elite tiers. When you have these conditions for a sport, an additional development category like under-23 makes sense to allow athletes to have the time to develop. It also enhances recruiting for the higher levels of teams."

There are under-23 riders securing contracts on the Women's WorldTeams. Still, most young riders are contracted with Continental teams. The second-tier teams are becoming essential for young riders to gain experience because they can offer a mixed calendar of lower-level .Pro, .1 and .2 events, while some also receive invitations to compete at select races on the Women's WorldTour.

"With the development of the Women's WorldTour, the smaller events are very important for the Continental teams and young riders. There needs to be a bigger vision, though. All races now want to be WorldTour to get those top teams and top riders, but those lower-level races are needed because it's hard to get into the bigger races, and for the younger women, there's no under-23 category for them to grow," Slappendel said.

"That is where [exiting junior] riders will develop, and for now, they need to start at the Continental level and race at lower-level elite events. The development structure is lacking at the moment for women's cycling. It needs a better plan. It needs a vision."

Kirsten Frattini is the Deputy Editor of Cyclingnews, overseeing the global racing content plan.

Kirsten has a background in Kinesiology and Health Science. She has been involved in cycling from the community and grassroots level to professional cycling's biggest races, reporting on the WorldTour, Spring Classics, Tours de France, World Championships and Olympic Games.

She began her sports journalism career with Cyclingnews as a North American Correspondent in 2006. In 2018, Kirsten became Women's Editor – overseeing the content strategy, race coverage and growth of women's professional cycling – before becoming Deputy Editor in 2023.