'It's real, mate' - When Hayman conquered Boonen at Paris-Roubaix

We look back on the biggest upset in recent history at the Hell of the North

After starting out as the brainchild of two Roubaix textile manufacturers who hoped to promote their newly built velodrome, Paris-Roubaix has grown into possibly the most popular one-day race on the current cycling calendar.

Cyclingnews' first encounter with the Hell of the North came in the early months of the site's existence in 1995. As it was in those days, the information was short and to the point, with little more than three paragraphs recounting Franco Ballerini's solo victory.

In subsequent years, Cyclingnews' coverage of races has expanded beyond recognition to those nascent days. Live text coverage of the biggest races has become an integral part of reporting on a race.

Paris-Roubaix is the perfect event for an age where content is consumed endlessly, and fans can watch entire races live on television. Rarely a moment passes when something isn't happening and there are few races as hard to predict. Writing the live text coverage for a race like this is both enjoyable and stressful because as soon as you look down to write an update something else has happened.

It is little surprise that Paris-Roubaix has been consistently at the top of polls for the best one-day race of the year. The Hell of the North has delivered us some of the most iconic racing days and picking a favourite is a next to impossible task but Cyclingnews readers did just that in a vote when they named the 2016 edition the best of the last 25 years.

In my time at Cyclingnews, 2016 was the only Paris-Roubaix I wasn't on the ground for. Instead, I was in the UK taking care of the website's live coverage. For my colleagues in Compiègne, it would be an early rise to make it to the start area somewhere between an hour and two before the race began. The clock was always ticking because you had to be on the road at least 10-15 minutes before the start. If you leave too late, then you can get stuck behind the peloton for some time as they roll through the neutral zone. I cut it fine one year and had to jump a fence to get to the car and barely made it out before the gendarmes closed the road.

The drive from Compiègne to the press room in the Stab Velodrome in Roubaix – adjacent to the open-air one where the race finishes – is close to two hours, but if you time your departure right then you can get a good parking spot and arrive before the riders hit the first cobbles. Marginal gains aren't just for cyclists, you know.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Back at home, I had no driving to do, but it would be all out as soon as the riders departed. On a big day like this, we would start our coverage about an hour beforehand and keep going for an hour, maybe more, after the riders finish. In all, it would be about seven hours of constantly tapping away at my computer trying to convey the madness that was unfolding in front of me.

End of an era

The 2016 Paris-Roubaix marked the end of an era after Fabian Cancellara announced he would retire at the end of the season. A win here would put him next to Roger De Vlaeminck and, his long-time rival, Tom Boonen as a four-time winner.

Boonen was in search of a fifth victory and the uncontested title of Monsieur Paris-Roubaix. Despite all the pre-race talk, the Belgian was adamant another place in the history books was not important to him.

"Records aren't anything special," he told journalists a few days before the race. "When you win a race a few times, there is always a chance of a record."

Cancellara was much less ambivalent as he spoke about waving goodbye to the Classics. Speaking at Trek-Segafredo's hotel on the outskirts of Bruges on the Friday before Paris-Roubaix, Cancellara described how he had become distant in the build-up to Tour of Flanders and, the night before De Ronde, he got just over five hours sleep. Preparing himself for his final Roubaix had been an equally emotional task.

"I know it's going to be damn hard, but I have to blind this out. That's probably harder than the race, to blind out everything that I achieved here," he said.

Of the two long-standing rivals, an in-form Cancellara looked most likely to take home the cobble trophy. Boonen had endured a disappointing Classics campaign and picked up a wrist injury in a crash en-route to 15th at the Tour of Flanders the week before.

If either Boonen or Cancellara were going to take the title, they would have to get through double world champion Peter Sagan. The Slovakian had finally taken his first monument title at Flanders after attacking on the Paterberg and soloing to victory. He was the red-hot favourite to win in Roubaix and anyone hoping to win would have to shake him off their wheel before the velodrome. If he won, he would join a very short list of riders that had completed the Flanders-Roubaix double, an achievement that Boonen and Cancellara had done twice each.

Defending champion John Degenkolb would not line-up in Compiègne as he was still recovering after he and several of his teammates were hit by a car during training in January. Also missing from start list was a future winner in Greg Van Avermaet, who crashed heavily during the Tour of Flanders. Despite this, there was a long list of Classics contenders searching for the win, including 2014 champion Niki Terpstra, Sep Vanmarcke, Alexander Kristoff and Zdenek Stybar.

No pressure

Not once was Mat Hayman, who was riding his 15th Paris-Roubaix, mentioned as a potential contender. In fact, as the Australian broadcast of the race got underway, former rider Henk Vogels questioned whether a local rider would even broach the top five and, if they did, it was likely to be Luke Durbridge or Heinrich Haussler in the hot seat. In any case, Orica-GreenEdge were looking to Jens Keukeleire, who had finished sixth the year before, as their team leader.

It is hardly surprising that Hayman evaded many people's radars completely. The then-37-year-old had won few races in his career and he had fractured his radius bone during the Opening Weekend in late February. He had spent the weeks in between riding on Zwift on his home trainer in his garage and had taken part in just two one-day races in Spain in the build-up to Paris-Roubaix.

With no pressure or expectation on his shoulders, Hayman was one of 16 riders that formed the early breakaway. They had almost four minutes' advantage when multiple time trial world champion Tony Martin, then riding for Etixx-QuickStep, started drilling it on the front on the Monchaux-sur-Ecaillon pavé sector following a crash in the bunch with a little over 100 kilometres remaining.

Martin's charge blew the peloton apart, distancing Sagan, Cancellara and his own teammate Terpstra. In a fraction of a second, the German, riding his first ever Paris-Roubaix, had efficiently eliminated the two biggest favourites. Martin continued to put riders to the sword over the next 10 kilometres and cut the already small group of favourites to a more manageable five.

Never too far from his super domestique was Boonen, expertly surviving each split as they came. There were still 18 sectors of cobbles and an awful lot of racing to come but Martin's efforts had curated two of the defining moments of the race.

As Boonen looked increasingly likely to take a record-breaking fifth title, Hayman was still sitting comfortably in the original breakaway. Being up front, Hayman could relax somewhat – as much as you can when you're riding Paris-Roubaix – and save some energy as he didn't have to battle for position in the peloton or fight to survive the splits.

"This is the one monument where you can do good things from the breakaway," he would say after the race.

Through the Arenberg, Sagan and an isolated Cancellara were still seeking to salvage their chances but there was little cohesion in the group. They had already lost a minute to Boonen and co with Martin still providing his freight train services.

At this point, the developments in the race were coming thick and fast and it felt like my fingers couldn't type fast enough. When you're working at the race itself, it's possible to sit in the press room and watch the race unfold on one of the many televisions. You make notes of what you can because they become vital when you're writing copy at the end of the day.

Cancellara's dreams end in mud

Having stayed up front for almost 200km, the breakaway was finally absorbed by the chasing Boonen group following sector 13. Onto Orchies and any hope that Cancellara had of a romantic ending to his Classics career ended with a heavy crash into the mud. Sagan avoided the fall but, with the power of the Swiss time triallist gone from the chase, his chances were all but dead in the water.

With 30 kilometres remaining, a leading group of 10, containing Boonen, Hayman, Haussler, Vanmarck, Edvald Boasson Hagen, Luke Rowe and Ian Stannard, still had a minute over Sagan. Even at this point, as the pundits on Australia's SBS broadcast discussed the ones to watch for victory, Hayman still missed the list of favourites. For what it's worth, I didn't think he would win either at the time, and I said so in my live commentary. I'd have bet my house on either Boonen or Boasson Hagen taking home the goods. It's a good job I didn't.

Camphin-en-Pévèle provided the final selection, trimming the group of 10 down to just five ahead of Carrefour de l'Arbre. Hayman almost came unstuck when the riders entered the five-star sector as Stannard misjudged a corner and nearly pushed the Australian off the road. Simultaneously, Vanmarcke launched a stinging attack and it looked like Hayman's day was finally done.

It wasn't.

"Hayman!" Exclaimed Robbie McEwan as the Orica-GreenEdge rider appeared at the back of the group on Gruson, while television cameras watched Boonen try to chase down Vanmarcke. He had made it back and his chances were increasing as his rivals burned matches trying to bring back the Belgian up front.

A race to the finish

The final major sector of cobbles arrives in Hem, just under 13 kilometres from the finish line in Roubaix. This is the point when most journalists dash away from their computers and head into the middle of the Roubaix Velodrome. Your pass is checked before you're funnelled into a narrow space beside the entrance to the velodrome and then spat out onto the track itself.

By the time you've taken up your position on the grass in the centre of the velodrome, there's probably less than 10 kilometres remaining. It's hard not to get a little bit excited by the experience as the atmosphere builds as the riders get ever closer. Once the race finishes, all hell breaks loose as you try to spot riders amid the mass of team members, media and whoever else has bagged a spot in the centre.

More and more restrictions have been put in place for the benefit of television over the years, but you can often get to where you need to be if you move quickly enough. Once you’re finished in the track centre there is the utter carnage of the team bus parking to navigate for a few more interviews before the press conferences.

No way

Attack after attack came as they closed in on the famed Roubaix velodrome. Boonen and Hayman entered through the gates first, soon joined by Vanmarcke and then Stannard and Boasson Hagen as the bell tolled for the final lap.

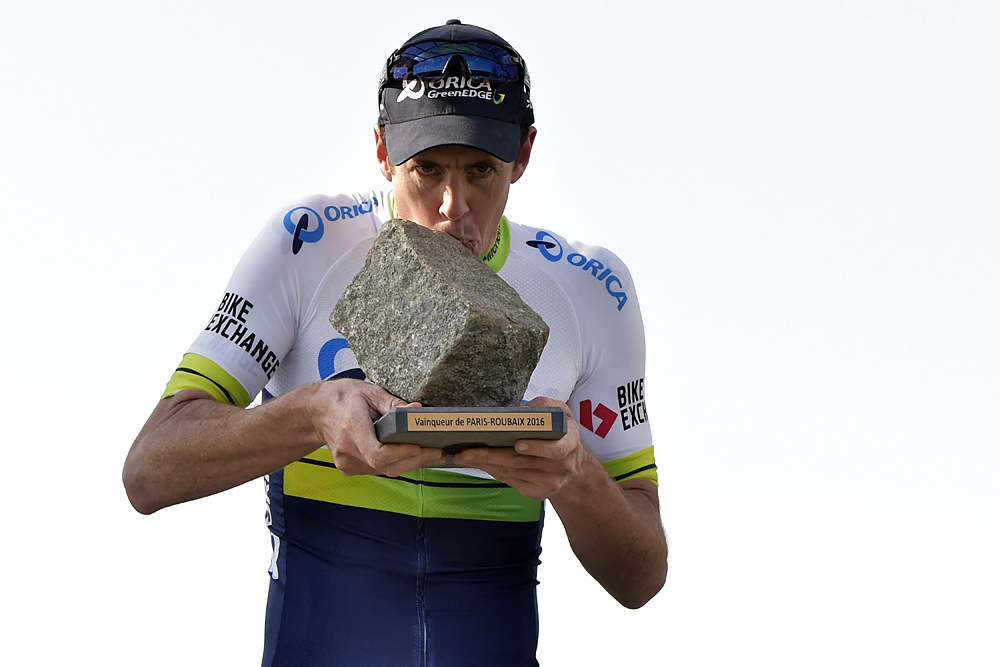

With half of the concrete track remaining, Hayman threw his chips down. He took to the front and never looked back, holding off Boonen on the line.

"No way", Hayman said with an expression of disbelief etched on his face, only to be told "It's real, mate!" by team videographer Dan Jones.

In a race where anything and everything is possible, being the underdog paid off for Hayman. "It's the one big race that throws up a surprise winner every once and again," Hayman said in his post-race press conference.

"It can be Stuart O'Grady or Johan Vansummeren. That keeps you holding onto that little bit of hope that one day it can be your turn. Today is my day and the sun is shining on me in the Roubaix velodrome.

"In the finale, those guys had to win. Boonen couldn't get second, Sep Vanmarcke wanted to win. Sure, I wanted to win too, but I could gamble and it paid off."

We didn't know it then, but it would be Boonen's last visit to the Roubaix podium. He would retire immediately after the classics the following year, finishing 13th at Paris-Roubaix.

"Mat was the rider nobody was really looking at," Boonen said. "A guy like him really deserves a victory like this after a career of helping people out and being in finales of classics a lot but not really getting the big wins."

Born in Ireland to a cycling family and later moved to the Isle of Man, so there was no surprise when I got into the sport. Studied sports journalism at university before going on to do a Masters in sports broadcast. After university I spent three months interning at Eurosport, where I covered the Tour de France. In 2012 I started at Procycling Magazine, before becoming the deputy editor of Procycling Week. I then joined Cyclingnews, in December 2013.