It's no fairytale - Book extract from 'Domestique' by Charly Wegelius

Helper finds himself off the front in sight of a first professional victory

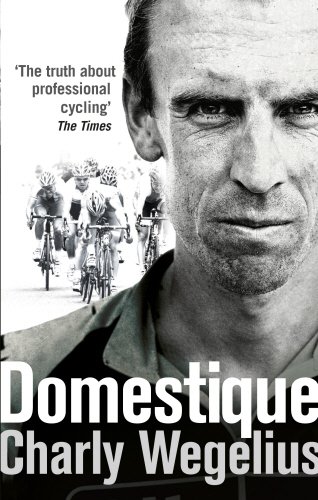

The following is an extract from ‘Domestique – The True Life Ups and Downs of a Tour Cyclist’ by Charly Wegelius and Tom Southam.

The book, published in 2013, focuses on Wegelius’ career, which was spent riding in the service of others. He started out as a professional with Mapei-QuickStep in 2000 and went on to ride for De Nardi, Liquigas, and Silence-Lotto, before ending a his career with lone campaign at United Healthcare in 2011.

This extract, the closing passage of the book, recounts stage 5 of that year’s Vuelta a Asturias, and the climb of the Alto del Naranco. With a dangerous group having stolen a march ahead of the final ascent, Wegelius drags his team leader Christian Meier back into contention, eventually making the junction under the flamme rouge. What happens next is entirely unexpected.

With his job done and "no failure left to fear that day", instinct takes over and he stamps on the pedals once more. Suddenly, he has a gap and, after a moment of doubt, he realises he’s alone at the head of the race, heading towards a first professional victory.

***

There were 600 metres between that uncrossed finish line and my front wheel. I could see the barriers that lined the final twists and turns towards that line. I was so close. I realised then that I wanted to win a professional bike race more than anything in the world.

My heart had been bursting out of my chest. Now it seemed to bury itself deep down into my stomach. I could see the metre boards as I passed them: 500 metres to go. I was inside the final barriers on the run-in to the line.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

I could no longer think of anyone else. I liked Christian Meier and I enjoyed working with him, but this was mine. This was for me. I didn’t need to impress my manager at UHC, I didn’t need to impress Damiani, or Amadio or Stanga or another manager who I hoped might want me in his team the next year.

I had been at the sharp end of a race before and I had missed out every time. At the Vuelta Pays Basque, at the Tour de Suisse and at the Giro I had been in winning situations where someone, somehow had got the better of me, had outraced me. I knew that it was a weak rider who would say he is cheated out of anything, but I had swallowed those failures in the only way that allowed me to deal with the constant defeat; I had pushed them far away.

I had ingrained it into my racing psyche that winning didn’t matter to me, that it wasn’t my role. I made myself so sensible and clinical that I persuaded myself that I didn’t give a fuck. I had found other things that I considered to be successes and I had gone after them instead, telling myself I was happy with closing a gap, or hurting people’s legs, and that it was enough that I was a professional cyclist without having to win races too. I had been like a jilted lover who couldn’t face committing to anyone again.

With 200 metres to the line I realised that what my head had been coldly telling me for so long was bullshit. I wanted to win. I had to win, and I was prepared to give my all for it.

By now, as I pushed on towards the line, my body was contorted with pain. I weighed each pedal stroke; there was no part of me that wasn’t committed to getting my bike across that line first and just once, after eleven years, raising my arms in the air.

I was so close now that a feeling rushed up from inside me that I hadn’t known for over ten years. It was like someone had dusted down my youth and handed it back to me. I was going to win. I knew it now, as I threw every part of my body into pedalling, all my composure gone. My physique, which I kept so perfect and still when I raced normally, was now bent over the bike – shoulders slumping from side to side and mouth gaping. I didn’t care what I looked like, or how I did it. I was going to win.

With 100 agonising uphill metres to go I suddenly felt that horrible chill of shock you feel just before the phone rings with bad news. I felt the fear pulse through me: the other riders. They were suddenly almost inexplicably there.

I heard them first, and then I saw them – Constantino Zaballa and Javier Moreno, the two riders who’d been in the break and whom I’d caught a kilometre earlier. They rode straight past without even looking at me. I couldn’t believe it. As soon as they passed me I stopped pedalling. It was over. Now, for all I cared, I could finish 80th or climb off my bike without even crossing the line. It had been all or nothing.

Those two riders fought out the win and I crossed the line in third feeling like I had just had my heart wrenched out of my chest. I didn’t know where to look or what to do. I slumped over my handlebars and began to weep. It was too much.

I had admitted to myself that there was no pride for me any more in being the rider who’d had a long, distinguished career but who’d never won a race. That was gone for ever now. I had exposed myself to thoughts that I’d hidden from myself for so long. I did want to win, and it did matter, and now I had to face it all.

As my emotions overwhelmed me it felt like the stitches on a wound had been torn open and everything poured out of me. I thought if I could have just won then it would all make sense: my whole career rounded off with a nice win at the top of a famous climb. It would make sense of the shit that I’d eaten through the winter, being kicked around by teams; it would make sense of eleven years of races I’d started with no intention of working for myself; the countless races where I’d turned inside out to be there in the finale, only for my leader not to even need me; the days away from my wife, the time away from my family, and the life I’d had to live to be a professional cyclist. It would have made sense of a long career of servitude, because it would have been mine, my personal triumph. It would have been one photograph I could put in a frame: me crossing the line a winner; cycling’s gift back to me. But it didn’t happen.

At that moment, as I sobbed into my hands and the tears mixed into the sweat and filth of the dirty roads that covered my face, I knew the truth about professional cycling: it’s no fucking fairytale.

‘Domestique – The True Life Ups and Downs of a Tour Cyclist’ by Charly Wegelius and Tom Southam is available to buy on Amazon.