In the tunnel with Magnus and Julian

Recent Team Slipstream/Chipotle additions David Zabriskie and David Millar are without a doubt the...

Tech Feature: Magnus Backstedt and Julian Dean wind tunnel testing, January 10, 2008

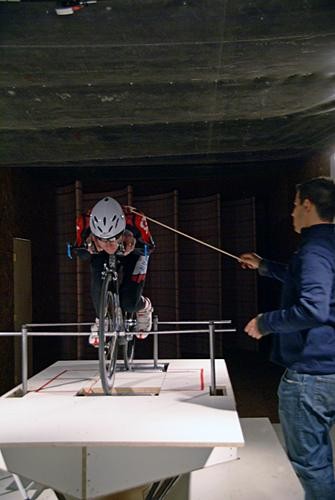

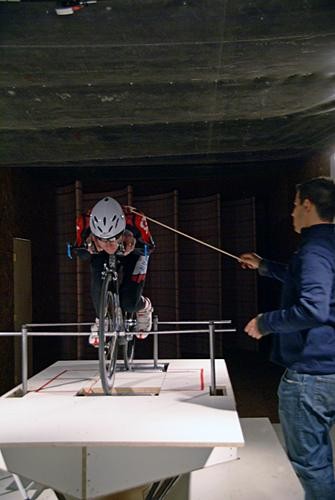

Team Slipstream/Chipotle presented by H3O riders David Zabriskie and David Millar may be the team's most obvious time trial talents, but they're not the only ones that stand to benefit from wind tunnel testing. Cyclingnews Tech Editor James Huang heads up to the Colorado Premier Training wind tunnel with new signings Magnus Backstedt and Julian Dean.

Recent Team Slipstream/Chipotle additions David Zabriskie and David Millar are without a doubt the team's time trial stars. Zabriskie is the US National Time Trial Champion, and has won time trial stages in the Tour de France, Giro d'Italia, Vuelta a España, and Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré. In the 2005 TdF, he recorded the fastest non-prologue time trial in Stage 1 with a blazing 54.676km/h average, besting Greg LeMond's sixteen year-old record by 0.222km/h, and even finished second overall at the 2006 Tour of California.

Teammate Millar is the current British Time Trial National Champion and his palmares includes TT wins in the Tour de France, Vuelta a España, Tour de l'Avenir, and Paris-Nice. Proving that he's no one-trick pony, though, he's also the current British National Champion on the road and is a former national title holder on the track in the individual pursuit as well.

Both Zabriskie and Millar fit the classic aesthetic mold with fluid pedaling styles and long, lean, and flexible physiques that display table-flat backs that mere mortals (and many pros) can only dream of. During the team's official presentation in November, it was a no-brainer for both to pay a visit to the recently established Colorado Premier Training wind tunnel facility in Fort Collins, Colorado. But does wind tunnel testing offer benefits for the team's non-specialists as well?

Everyone can always go faster

Magnus Backstedt, another new addition to the team, is commonly referred to as a one-day and Classics specialist: he won Stage 19 in the 1998 TdF, he was Swedish National Champion on the road in 2002, and landed a glorious win at Paris-Roubaix in 2004 plus a second place finish at Gent-Wevelgem that same year. Backstedt is no slouch when it comes to rides against the clock, though: in 2003 he was the Swedish National Time Trial Champion.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Still, at 1.93m tall and weighing 93kg (6'4", 205lb), Backstedt is 8cm taller and 13kg heavier than professional cycling's other time trialist archetype, Fabian Cancellara (Team CSC). When you're punching that big of a hole in the air, how much good can wind tunnel testing really do?

Plenty, if you ask Slipstream Team Physiologist Allen Lim, who reminds us that an effective time trial is also about power, not just aerodynamics. "The size of Magnus doesn't necessarily present so much of a problem than it does a possibility," he said. "Aerodynamic drag and power scale differently so in concept, a bigger guy that is as elite as Magnus actually has an advantage over smaller climbers that don't produce nearly as much power relative to their frontal area."

Backstedt certainly has the power issue nailed: according to him, he can maintain a 575-580W output during a pursuit event on the track, and has seen a spike as high as 2000W in a sprint. Although the team's test period in November was primarily held to collect baseline data for further improvement, even just a 2cm change in Backstedt's bar height yielded an 8W savings at typical TT speeds.

Similarly, sprint and leadout specialist Julian Dean doesn't normally think of the air as being his primary rival. At the 50-60km/h finishing speeds common in today's most hotly contested finishes, though, it's more likely that the majority of Dean's energy is working against wind resistance, not the guy next to him. As such, just as refining positions in the wind tunnel can also improve time trial standings, subtle changes to Dean's sprint position can produce marked improvements in his top-end speed as the finish line draws near. Lim even goes one step further: "[Aerodynamics] is almost more important for sprinters."

Dean will continue to refine his position in the coming months, but at about 50km/h, wedging himself deep into the drops saved an enormous 140W versus being on the hoods, or roughly what typical amateur riders put out on average during a normal ride. What's the point of taking a measurement in the hoods if none of the sprinters actually use them at the finish, you wonder? If you recall, Cancellara jumped clear and took a surprise victory in Stage 3 of this year's TdF by just a few meters… with his hands firmly placed on the hoods. Now think this to yourself: what would his margin of victory have been if he were in the drops?

What will Backstedt ride in this year's Paris-Roubaix?

The New Year is still fresh on most people's minds, but the start of the racing season is just around the corner: Australia's Tour Down Under begins in less than two weeks, the Tour de Langkawi kicks off in one month, and the Tour of California rolls out shortly thereafter.

The spring Classics aren't much further behind and 2004 Paris-Roubaix winner Magnus Backstedt is already well along in his planning for this year's event. "We've already started testing the standard bikes that [Felt] have in-house; we don't really want to start to try and design something new [if we can] work with what they have and then go forward with that," he said. "So far I've tried the Z1 frame and I think it's actually going to be the one that I'm riding due to the angles and things. After that, it's just getting it stiff enough where I need it; the front end is a little too soft on me so far. Most of the time the biggest problem we see is [tire] clearance."

Some may be surprised that Backstedt would 'lower' himself to using a (mostly) stock frame for his top goal of the season, but it turns out that that is by choice, not obligation. "There are guys that play around with the geometry of the frame, with a longer wheelbase and that… I'm not that kind of a guy. I get used to riding on a bike and generally try to stick with that bike. Otherwise it changes the character of the bike. You don't know how it handles when you get on cobbles, especially if it's wet. I've found if you make a longer wheelbase bike, the bike is slower in the handling. It's steadier to ride, but at the same time, when the bike starts sliding around, you need to pick it up quickly. If you've been used to riding that bike the whole year, you know how it handles. Chances are you're going to have a few two-wheel slides through the corners a few times early on the season. At least when you get [to Paris-Roubaix], you know what's going to happen to the bike in that situation."

Backstedt is, again, surprisingly easy to satisfy when it comes to the matching equipment in that stock offerings more than suffice for getting the job done. As one would expect, though, wheels are still the critical factor in the componentry selection. "The biggest problem I have is to find the wheels that work. They need to be as aerodynamic as possible, obviously, but also you need them to be strong but fairly flexible. I had generally been riding a climbing wheel like the Campagnolo Neutron. That's [been] my Paris-Roubaix wheel: twenty-four spokes in the front, twenty-eight rear, no weldings, or tying-and-soldering of the spokes or anything like that. After that, the only thing I actually change in my bike is the padding on the handlebar which generally works out to be some sort of pipe insulation that I cut up into bits and pieces and fit where I need them to be. That's it. The more you try and go and overdue it, the more pieces you have that can break. [It's best to have] as standard a bike as possible, with no extras on it. The most important things are the wheels and fork."

Paris-Roubaix is still a few months away, but it may as well be just around the corner as far as Backstedt is concerned. "I do quite of testing on the stones in Belgium and I'll probably go over there three or four times before we actually get to the race up there. I'll go over the course so I know it, I know the equipment I'm going to ride… everything is ready at least a month in advance, sitting in the truck, ready to take out."