In search of Abdou, part 2: The Tashkent Terror

The first man to refer to Abdoujaparov as "The Tashkent Terror" was apparently Procycling co-founder...

Tales from the peloton, June 28, 2008

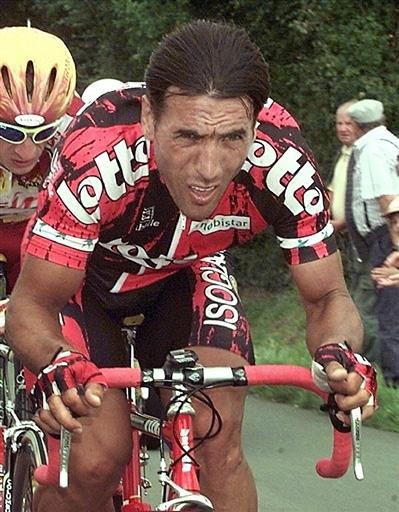

Djamolidine Abdoujaparov was one of the most feared sprinters in the peloton during the early to mid-90s, not least for his erratic style in sight of the line. Procycling's Daniel Friebe tries to find out what "The Tashkent Terror" is doing now, but discovers it's not that easy. Continued from part one.

The first man to refer to Abdoujaparov as "The Tashkent Terror" was apparently Procycling co-founder William Fotheringham, now an award-winning author and Guardian sports writer.

When he learns of our quest, William sends in a few of his old Guardian cuttings from the Tour during the early 90s. He scrawls a note on one of them: "Those were the days. No doping scandals and lots of big characters!"

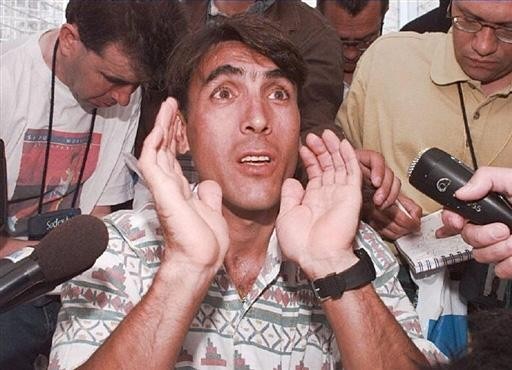

Before he came up with "The Tashkent Terror", Fotheringham used to call Abdou "The Baby Eater". The sort of material that would have graced any Marvel comic strip, Abdou's feud with Mario Cipollini is lip-lickingly chronicled in Fotheringham's reports.

Thus, a preview of the 1992 Tour recalls how the rivalry was never more toxic than at that year's Gent-Wevelgem, where, after his disqualification for erratic sprinting handed the Italian his first victory in the Belgian semi-Classic, Abdou accused Cipollini of "buying the jury". Cipollini issued his retort live on Italian TV: "If I find him in the showers, I'll tear him to pieces."

It's little surprise that a ceasefire brokered by the Italian riders' union in spring 2002 lasted no more than a few weeks.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"There was 'Tashkent Terror', but also 'Tashkent Terminator' – because he kept crashing and getting back on his bike like nothing had happened," Fotheringham reminisces. "I can remember them showing the clip of his crash on the Champs Élysées at the 1992 Tour presentation, and poor old Abdou just sitting there looking sheepish while everyone else fell about laughing. Then there was the feud with Cipollini – 'The Tashkent Terror' versus 'Super Mario'. It was all great theatre. And Abdou, well, he was like Robert Millar with a language barrier... Those were the days, eh?"

Filling in the gaps

I now know where Abdoujaparov lives, I have his phone number and I could call it whenever I want, but, for some reason, I'd rather wait. Just a few more calls to make, a few more gaps to fill in.

Konyshev has confirmed what I've heard about him coaching, or at least mentoring, juniors in Russia, so I decide to pursue that avenue. I call the Russian federation, ask them what they know about Abdou, and again sense suspicion rippling down the phone.

"I'm not sure I can tell you [what he's doing with the federation]. Call back tomorrow and speak to the president, Alexander Gusyatnikov," I'm told by the only French speaker in the office, who interrupts the conversation several times to consult with colleagues. The next day, Gusyatnikov informs me through a makeshift translator that, having collaborated with them for two years in Samara, Abdou recently stopped working with the federation. The conversation is stilted to say the least, but I gather that Abdou was more of an occasional consultant than a coach, and that the partnership broke down more due to the logistical problems of commuting between Russia and Lake Garda than because of any dispute.

Does Gusyatnikov know what Abdoujaparov's doing now? What do you think?

The search gets desperate

The search for background info – something, anything – on Abdou is getting desperate. How desperate? Well, what would you call spending an hour looking up pigeon breeders in the north of Italy, scouring competition results for his name, then finally calling up what would surely be Abdou's local pigeon club, the Leonessa of Brescia, and quizzing its president Sergio Bresciannini?

Sure, Bresciannini knows the name, but only from old TV broadcasts of the Tour.

The internet doesn't help much, either. A polyglot acquaintance searches in Russian, but regretfully informs me a few days later that she's found nothing. There are one or two references on forums to him coaching in Russia or Uzbekistan, and even speculation on a French site that he spent years in France "living with an old woman" – Madeleine Baillart, we presume – but little of any real authority.

Baillart, incidentally, told L'Equipe in 2001 that she'd advised Abdou to "start a business selling typical French products", but that "he's always dreamed of having his own brand of bikes". According to the old lady, within a year or two of his retirement, he'd hit financial trouble and was forced to sell a car to raise some petty cash. One of the Uzbek's former directeurs sportifs scoffs at the idea: "He used to ask for 12,500 tax-free at the post- race criteriums! He'll never have to work again. If he was working for a tyre-dealer, it was only to make sure the immigration authorities let him stay in Italy!"

Contact! Sort of...

April 16, 2008. It's nearly five o'clock – Abdou time.

In truth, we've already tried several times and gone straight through to an automated message service. This is the first time we've heard ringing.

Four rings, five, six and, then, just when hope is fading...

"Si?"

"Abdoujaparov?"

"Sì. Who is it?"

It's not the voice of a man who sounds like he expects or particularly wants to be contacted.

"I'm a journalist from Procycling in London. I was wondering whether I could ask you a few questions about what you've been doing since you retired..."

"Who gave you my number?" he barks.

"Dimitri Konyshev"

"Hmmm... Call me Sunday"

We hesitate. "Sunday" sounds a little vague for us, especially coming from a man who makes the Loch Ness Monster seem like a paragon of ubiquity. We try to tie him down...

"What time shall we call? Midday?"

He now sounds impatient and angry...

"I don't know! Sunday, whenever on Sunday! Midday then. Call me at midday!"

The phone goes dead. There's no time for an arrivederci.

Perhaps like a lot of people, to my mind the most memorable of all Abdou's nine Tour de France stage victories didn't come in a mass sprint, but rather in an unlikely solo break in the Massif Central.

On that day in 1996, it just so happened that I was on holiday with my family a few kilometres from where The Tashkent Terror was stomping grimly away from his four fellow escapees to win in Tulle, and I spent the afternoon glued to the TV. Even for a 15 year-old following his first ever Tour de France, the notion of a muscle-bound sprinter dictating things in the hills somehow seemed bizarre.

Almost 12 years on, it's tempting to imagine that Abdou set out on a much longer breakaway that day – one which still hasn't ended today. Within a year, he had been sent home from the Tour after the latest of a mind-boggling sequence of six positive dope tests, this time for the steroid Clenbuterol and the stimulant Bromantan. At 33, his career was over.

"I heard a rumour – but I mean maybe a fifth-hand rumour – that he was so sick of cycling in his last year that he just stuffed himself full of drugs in a deliberate attempt to get caught and finish his career," says Marcel Wüst, who frequently locked horns with Abdou in sprints in the early 90s. "I think he was just fed up of riding his bike. His positive test was the last I heard of him. I can imagine he's chopping wood in some forest in Uzbekistan now. That's just what he always looked like he should be doing...

"I was scared of him, on the bike and off it," Wüst continues. "Without really talking to him very much, I guess I just assumed that he was as nasty a person as he was a sprinter. People like Robbie McEwen and Jeroen Blijlevens were friendly, happy guys who would turn nasty at the end of a race. To look at Abdou, you just got the impression he was nasty all the time.

"No one wanted to be close to him in a sprint. The problem with his sprinting style was that, even when he was going in a straight line, the bike would be moving around so much underneath him that he'd take up a metre and a half of road. He was the most dangerous bike rider I've ever seen."

Wüst interviews McEwen in a Procycling feature, and reports back that the Australian knows no more than he does about Abdou's recent past. Others draw blanks too: Maurizio Piovani, his directeur sportif at Lampre in 1993, concedes he has no idea what Abdou's doing now; the agent Alex Carera lives a short drive from Raffa and knows every cyclist within a 200km radius of Lake Garda but can't find anyone who can help us solve this brainteaser; journalists from all over Europe, who smile wistfully at their own favourite Abdou memory, tell you you're onto a great feature, but then curl their bottom lip or puff their cheeks when you ask if they can help.

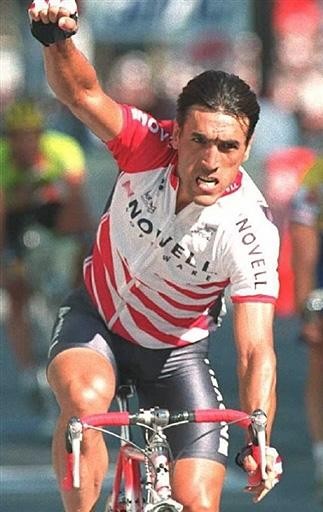

Then there are just those who throw us completely, like Abdou's old team-mate at Novell in 1995, Viatcheslav Ekimov. He tells Procycling contributor Jason Sumner that he last saw Abdou two years ago in Italy, that he was running a bar and supporting a junior team. "I have no clue what he's doing now, but I hear he takes good care of himself and is riding the bike," the Astana directeur sportif adds.

It's now dawning on us that the more we dig, the more dirt flies up into our eyes. We decide that the next port of call had better be our last.

As he emerges from his Collstrop team motorhome in Charleroi on the morning of Flèche Wallonne, we approach Serhiy Lagutin, the 2003 under-23 world champion and now one of only a handful of Uzbek riders in the pro peloton.

We cross our fingers.

"I had a bit of contact with him until three years ago; he used to help bring junior riders and amateurs from Uzbekistan to Italy, find them teams and a place to live, but I haven't seen him for two or three years," Lagutin tells us, somewhat crushingly.

"He has a bit of a funny character.Everyone has to do what he says, even if he's wrong. He's had a lot of fights with people. I didn't fight with him, but I haven't seen him for three years. He was always a bit old school. He's got a strong, strange character..."

We tell Lagutin about our brief telephone exchange, and how Abdou was clearly less than delighted that we'd found his number.

Lagutin grins. "He's always like that with everyone," he says. "It's always, 'Who gave you my number? Who gave you permission to call me?'

"To be honest, I've heard all sorts of things about him," he continues, fighting back a smirk laden with innuendo.

"Someone told me he has a hotel, someone else told me he had a petrol station, someone said he was going to sell Colnago bikes in Russia... He was a hero in Uzbekistan, but not so much now. He hasn't been back for 10 or 15 years. Everyone knows the name, but beyond that most people have forgotten about him."

"Whosoever is delighted in solitude, is either a wild beast or a god," Plato once wisely remarked.

We start calling on Sunday at midday. Abdou never does pick up again....

Delighted in solitude? Maybe, maybe not.

Return to part one of In search of Abdou...