I wanted to hold up a sign - 'Get me out of here!'

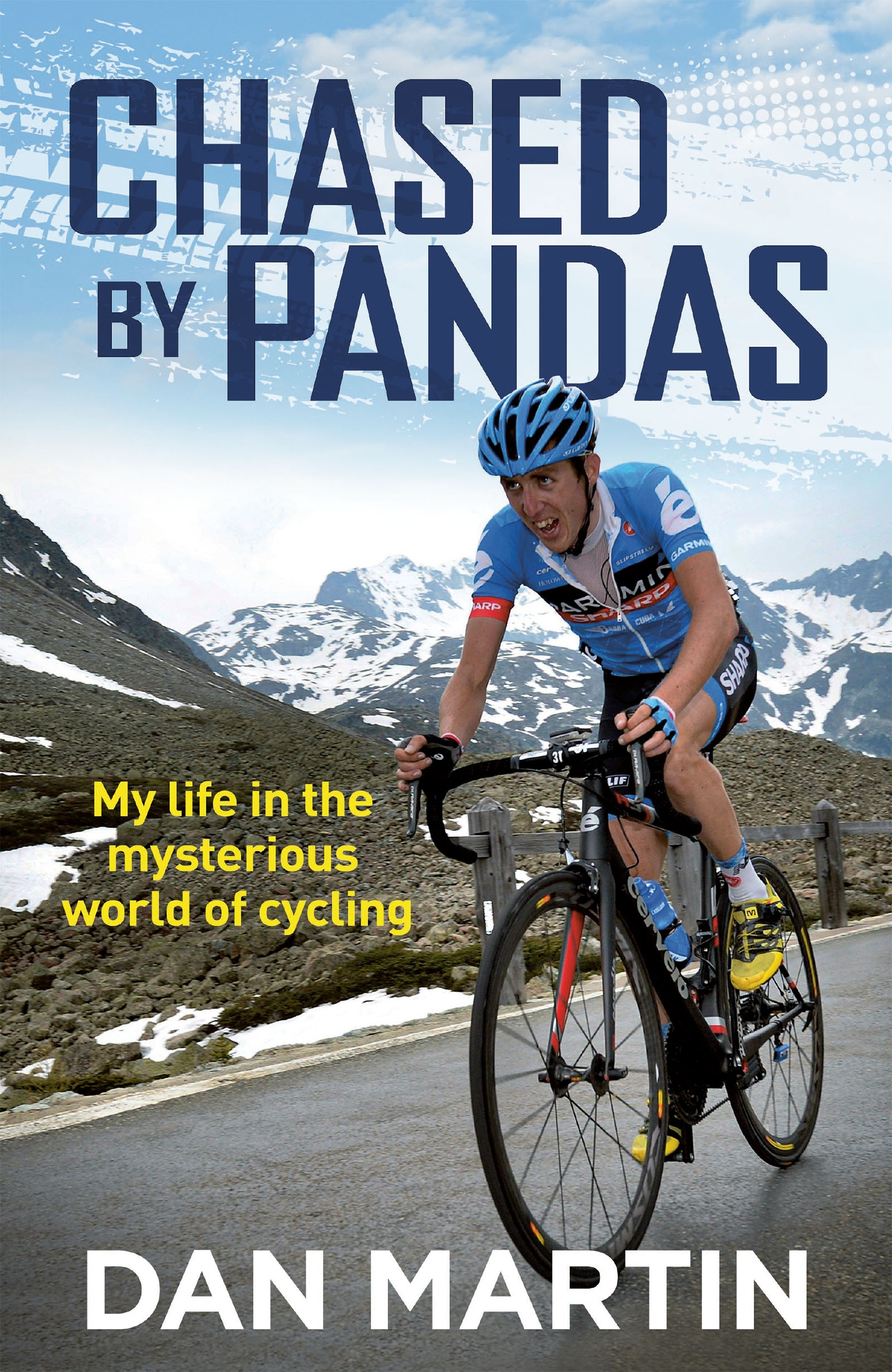

Dan Martin describes his split with Vaughters/Slipstream in an excerpt of his new book Chased by Pandas

In Dan Martin's new book Chased by Pandas: My Life in the Mysterious World of Cycling, he reveals the inner workings of the sport. In this excerpt, Chapter 15: The Race of Broken Bones (The Fear of Destroying Your Body), he describes how his relationship with the Garmin-Slipstream team fell apart. Reprinted with permission from Quercus.

It hurt every time I caught my breath, thousands of times a day, until the pain became a part of me and of my routine. I put a lid on it but, deep inside me, it pushed and tapped, wanting to come out of its box, and at those moments a silent scream of agony ran through my head. What hurt the most was that I hadn’t chosen to be in this situation. I shouldn't have been suffering. Instead of struggling every day, racing with broken ribs on Swiss roads at the Tour de Romandie, I should have been resting at home. But my team denied me that option. It prolonged the torment.

... (Clipped for brevity - ed.)

The Tour de Romandie starts two days after Liège–Bastogne–Liège, but you don't often go there after racing the Classics. The event marks the real start of the stage racing campaign for GC riders. When you're there you focus on not getting sick, by covering your chest with newspaper at the top of the passes, for instance, and drinking a cup of hot tea before going to bed – doing things the old-fashioned way.

The Tour de Romandie is often more of a winter race than a spring one; the snow is only just starting to melt and icy gusts blast down the valleys, which are thick with cold fog hanging over the lakes. It's not uncommon for the queen stage to be shortened or completely wiped from the race map. But not that year. I was in for the whole shebang.

I thought I might be eliminated in the team time trial, dropped after 600 metres, left adrift on my own and, ultimately, outside the time limit. But I was wrong. I managed to hold on to the wheels of my teammates for the whole 19-kilometre test, which we covered at an average speed of more than 50km/h. That evening I reflected on what my directeur sportif had said. 'The pain will ease as the days go by.' Would things actually turn out the way he'd suggested?

That night, it quickly became apparent that they wouldn't. The pain persisted. It felt like a needle was piercing my stomach every time I breathed. I thought I had at least one broken rib, probably two, maybe three. I was really worried about the fact that I was racing rather than resting. I'd heard that some rib fractures develop into pneumopathy and that to prevent this you need to cough regularly or take deep breaths. By spacing out those breaths, I could space out the pain. But as I lay in bed, I felt it getting worse. I almost longed for breathlessness.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

I turned to the teammates I was closest to, like my mate Nathan Haas, who was always there for me. They reassured me and promised to help me, even though there wasn't really much they could do for me. I also got some pretty blunt advice from the directeurs sportifs, Guidi and Andreas Klier – the latter I knew well; he had been a great roommate on the Vuelta four years earlier. The pair of them urged me to stick at it, accentuating what they believed to be the common interest of both team and rider, and insisting that I needed to hold on to the idea that you should never give up. They pushed me day after day, just as they used to when they were encouraging us on a climb: 'Hang on! Come on! Only three kilometres to go! Only two to go! Grit your teeth, last kilometre!'

The idea of using painkillers was of course an option, but it wouldn't resolve the problem. The pain was actually my body's way of protecting me, of preventing me from pushing myself beyond my limits. Every rider has stories of colleagues who have sacrificed their wellbeing by pushing themselves on a damaged bone, knee or tendon. Over the course of just a handful of days, even a single race sometimes, they ended up ruining their careers and prematurely ageing their bodies. I'd rather suffer than destroy myself.

The team didn't understand my refusal to use painkillers and perhaps, after looking back, neither do I but at that point it was a form of protest as for me I was in open dissent, half following orders, half disobeying them. Racing? Yes. Painkillers? No. However, I wanted to make my team managers aware of their responsibilities. Every day I would ask: 'Can I go home tomorrow?' And they would answer: 'One more stage and we'll see...' After the third stage, I sent an email to our logistics manager asking for an emergency plane ticket to Barcelona. This was refused. I suspected that they weren't solely responsible for this decision, but during this whole period I didn't hear anything from our big boss, Jonathan Vaughters – not before, during, nor even after the Tour de Romandie. But I can only assume that he must have been behind the decision for me to stay in the race.

On the fourth stage, my ordeal became clearly apparent. I was dropped after about 20 kilometres, on an easy climb. The occupants of other team cars stared at me. I wanted to hold up a sign: 'Get me out of here!' I finished in a gruppetto that came in twelve minutes behind the winner. On the fifth stage, I lost another twenty-two minutes.

To keep myself going, I thought of riders who'd been even less fortunate than me in their careers.

...(Clipped for brevity - ed.)

Compared to riders who'd had to cut short their careers prematurely or suffered serious injury, and even more so to children who were fighting to stay alive, I was lucky. Very lucky.

All I wanted at the Tour de Romandie was for the ordeal inflicted on me by my team to end. I asked for permission to sit out the final stage, a 17-kilometre time trial through the streets of Lausanne. The team insisted that I start. Very well, I'd do it. This was now a contest, their obstinacy fighting mine. I started the TT on a normal road bike because I found it too painful to get into an aerodynamic tuck on my time trial machine. I finished the time trial and with it the Tour de Romandie. I was 104th, one hour and sixteen minutes behind Russia's Ilnur Zakarin. The next day, I decided to take myself off for an X-ray. And what did they find? I did indeed have two broken ribs.

I never found out why my team had treated me so badly. Did they want to ensure that the Tour de Romandie organisers paid up the full costs for their participation in the race? Did they want me to go hunting for UCI points, which we were short of collectively and which we theoretically required to remain at World Tour level the following season? Were they punishing me for a lack of results? That year, I had finished 10th overall in the Tour of Catalunya and 15th in the Amstel Gold Race, before crashing twice in the Ardennes Classics. I'd also been expecting to do better, but that didn't mean that I had to be penalised.

Had the team's management suffered a crisis of confidence, believing that I didn't want to race when in actual fact I simply couldn't? The team had got to know me over more than seven years and were certainly well aware that I never shied away from racing, that I always did everything I possibly could. They also knew which buttons to push in order to make me react: pride, courage, and a hatred of complaining. They'd already provoked me in a very similar situation during the 2012 Critérium du Dauphiné, when they urged me to finish whatever the cost, even though I had a broken shoulder blade (unknown to me at the time) and couldn't hold the bars. Cycling is always about pushing yourself further, but I'd expected that a team would draw the line when it came to wanting an injured and groggy rider to race. I wasn't expecting them to insist on the rider racing if he'd asked to go home. As soon as a rider sustains an injury, they should be taken at their word, and protected.

Was this a case of wanting to put me under pressure because my contract was coming to an end and renegotiations were about to begin?

More than the broken bones, it was the attitude of my team's management that hurt me. How quickly things change! In 2013, the team had been very considerate when I had a concussion at the Vuelta. In 2014, they had paid for me to have surgery on my collarbone after I crashed on the opening day of the Giro.

I had first been taken to Belfast Hospital for examination, accompanied by our team doctor Kevin Sprouse directly from the race, but due to the incident occurring in the United Kingdom, the team's insurance company placed the responsibility for payment onto the National Health Service whose normal practice is to not operate on collarbone fractures, despite it being severely displaced. After some phone calls to the friends who I had worked with at the Cycle4Life events, Darragh and Cian Lynch, we managed to organize surgery in a private Dublin hospital not just for myself, but also Koldo Fernández. I was very grateful to Team Garmin for not hesitating in covering the entirety of the medical costs.

I was back with the team for the 2015 Tour de France. Two months after my crashes, with my ribs by then repaired, my morale had just about been replenished too. The start of the race in the Netherlands appeared to be beset with potential traps. The first road stage ended with a section alongside the sea on roads washed by the tides, and then crossed a very windy dike to reach the artificial island of Neeltje Jans. The second stage featured parts of the Flèche Wallonne route, the race where in the spring I'd hit the tarmac. The day before the start, we gathered at our hotel in Utrecht for our ritual pre-Tour meeting.

It was a chance for all of us, both the riders and the directeurs sportifs, to say some final words.

When it was my turn to speak, I said: 'I usually target stage wins rather than the general classification, but for once I'd like to go for a high overall finish. So, it would be ideal to avoid any stupid time losses in the opening days, in echelons perhaps or if the bunch splits going into a finish. It would be good for the team to help me out a little bit sometimes.' Charly Wegelius, our directeur sportif, didn't hold back. In his calm, monotone voice he pointed out that it was a pointless endeavour and that I was not a rider who had any chance of achieving a high finish in the general classification.

Under normal circumstances, a team manager would have mumbled something like, 'OK, that's fine, good idea, we know you've got great legs,' even if they didn't believe it. The internal psychology of a team is based on the idea of making athletes who can't achieve a particular goal believe that they can – not the other way around. I'd been humiliated in front of everyone, even though I'd finished seventh in the Vuelta towards the end of the previous season; the top ten could have been within my reach. Deep down, I felt like I was at the same point as five years earlier, when Matt White had expressed regrets over my performance at my first Giro.* Maybe this was an instructive moment; it appeared the team hadn't taken on board the experience I'd gained and still regarded me as the new pro they'd signed in 2008.

The incident that I'd been afraid might happen occurred on the fourth stage when we were racing across the cobbles in northern France. I fell on a wet road 5 kilometres before the first section of pavé. I wasn't hurt, but I ended up losing five minutes and thirty-seven seconds. Some of my teammates stayed with me and did all they could to help me, notably Jack Bauer, Nathan Haas and Sebastian Langeveld. I was pleased to see that the other riders hadn't lost confidence in me and still wanted to do what they could for me.

On the other hand, Charly Wegelius' attitude at the finish once again disappointed me. His evident sarcasm as he offered some words of support highlighted his contempt: 'We thought you'd lose five minutes, and you lost five minutes. That's not so bad, it could have been worse.' On paper, a climber is always going to struggle on the cobbles. But I couldn't take this defeatism any longer. Charly, the team's head honcho during the Tour, chipped in again a couple of days later.

He had seen me at the back of the peloton coming into the final 10km and questioned my positioning. At this point I was not in the fight for the overall, so for me it was worth the risk of a small time loss to stay out of trouble, as most crashes happened at the front. And I was also saving energy. Charly disagreed, and told me that if I was serious I would always be at the front. His attitude just didn't make sense to me anymore. I was actually following his instructions by turning my attention towards stage victories, but he still made a point to deride me.

Jonathan Vaughters, who had not been in contact for several weeks, came out of the woodwork during the Tour de France. Quite unexpectedly, he offered to extend my contract. The discussions around this were like those you might have at the tomato stall on Girona market at the end of the day, when you were trying to pick up five boxes for the price of one. JV began by putting an offer on the table that was worth a quarter of what I was currently earning. He'd spoken to my agent, Martijn Berkhout, who humorously replied: 'Thank you for your offer. It's a very good bonus. Can we talk about his salary now?'

Every couple of days my price changed, in informal discussions that were carried out by text message. Vaughters' offer would plummet when I finished in the middle of the pack, then, after my second place finishes at Mûr-de-Bretagne and Cauterets, he would raise it slightly. But still, in the best-case scenario, he wanted to halve my salary. However, it was no longer a question of money. I wouldn't have stayed, not even for 10 million euros. After eight years of great adventures and memorable moments with this team, I needed to regain a bit of dignity.