How to measure a bike frame

All the measurements that go to make up a bike’s geometry explained

For a simple machine, a bike is actually quite complex. How it rides and how easy it is to operate will be affected by considerations such as its groupset and gearing, wheels and tyres. That’s before you consider frame materials and construction and a bike’s aerodynamics.

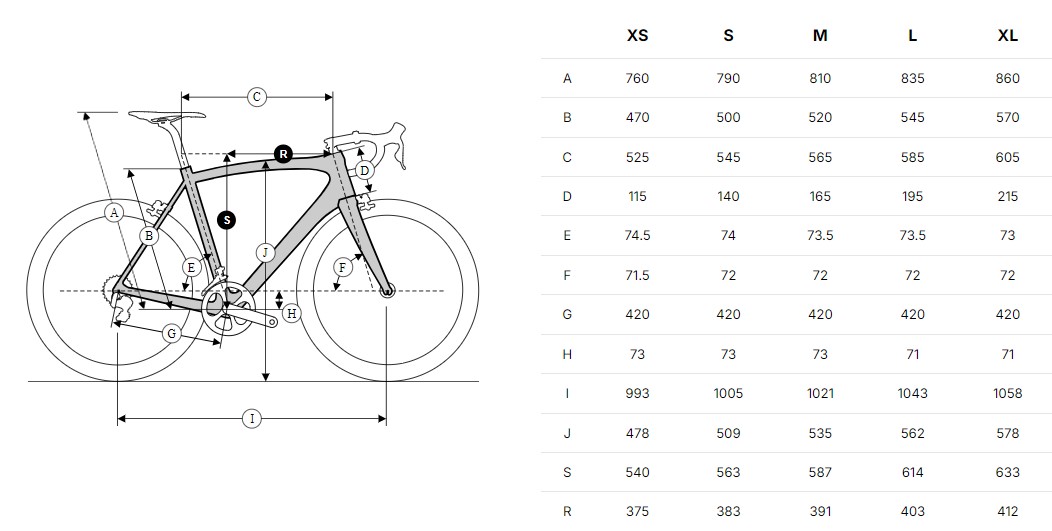

But the most significant impact on a bike’s handling and ride characteristics is its frame’s geometry. A geometry chart will feature in the specifications for almost every bike and can be found online on bike makers’ and retailers’ product pages.

Usually accompanied by an annotated diagram of the bike’s frame, the geometry chart is a series of linear and angular measurements which define a bike's geometry and will differ by frame size. But what do all the figures mean and how do they affect the bike's fit and ride?

We’ll run through how a bike frame is measured, with all the numbers that make up a bike geometry chart, and their significance. It’s worth noting that while linear measurements may be quoted in millimetres or centimetres, angles are always in degrees.

Seat tube length

Seat tube length is the distance from the centre of the bottom bracket shell to the top of the seat tube.

It’s an important measurement to determine bike fit and is one of the principal measurements used to denote frame size, alongside a more generic S, M, L sizing. Some brands have their own sizing system though – Colnago is the classic example, although other brands such as Moots go their own way too.

Seat tube angle

The seat tube angle is the angle that the seat tube makes with the horizontal. In general, more racy bikes tend to have steeper seat tube angles and time trial and triathlon bikes much steeper seat tube angles than road bikes.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Some seat tubes are kinked or curved, so you may see a virtual seat tube angle on a geo chart. Suspension may also change the seat tube angle, as most systems have sag in them, where the rear of the bike is compressed when a rider sits on it, changing the seat tube angle. In such cases, you may see an effective seat tube angle quoted as well as a sag-free angle.

Head tube length

The head tube length is the distance from the bottom to the top of the bike’s head tube. In general, a longer head tube will increase a bike’s stack (see below) and provide a more upright ride position, so you’re more likely to see a longer head tube in an endurance bike.

There are exceptions though, as the frame stack is a combination of the head tube and fork length. The trend to fit wider (and therefore taller) tyres means that fork length to the fork crown (the bit where it meets the frame) may be longer than on a bike designed for narrower tyres, providing additional clearance, and systems such as Specialized’s Future Shock also add height to the fork. In such cases, a shorter head tube length may not indicate a lower stack and racier riding position.

Head tube angle

As with the seat tube, the head tube will make an angle with the horizontal. This is usually greater than 70 degrees on performance road race bikes. Gravel bikes may have a slacker head tube angle and the trend is towards lower angles, in some cases considerably below 70 degrees.

Top tube length

Top tube length used to be a main measurement used to denote bike sizing. But the advent of the sloping top tube, which was first introduced on the Giant TCR in 1997, means that the actual top tube length is highly dependent on the frame’s design.

So now you’ll usually see a horizontal top tube/virtual top tube measurement quoted in bike geo charts, sometimes accompanied by an actual top tube measurement. Virtual top tube is the distance from the top centre of the head tube horizontally to where the measurement intersects the seat tube/seatpost and so is independent of the actual top tube slope.

Fork rake

The fork rake is the distance that the fork dropouts are in front of a straight line continuing at the same angle as the head tube. A greater rake will put the front wheel further in front of you.

It’s one of the reasons why classic steel bikes have curvy fork blades, although it’s now more usual for the fork blades to be straight, but angled at the fork crown.

Trail

Trail is the horizontal distance between a continuation of the fork rake to the ground and a vertical line from the axle dropout to the ground. The trail affects how edgy the steering feels, with a longer trail adding stability. Counterintuitively, a greater fork rake will result in a shorter trail.

Trail is also affected by wheel and tyre diameter, so in some cases bike brands will quote trail figures for different tyre sizes. It’s the reason why some brands, including Cervélo and Ruut incorporate a 'flip chip' in the front dropout of their gravel bikes to alter handling characteristics.

Bottom bracket drop

The centre of the bottom bracket is closer to the ground than the bike’s axles. How much closer is measured by the bottom bracket drop. A larger bottom bracket drop will tend to enhance a bike’s stability, while less drop will make for an edgier ride.

A lower bottom bracket will also put your pedals closer to the ground, and can result in pedal strike in extreme cases if you're pedalling while leaning over very hard in a corner. In order to deal with riding off-camber slopes cyclocross bikes often have quite high bottom brackets, or a very small bottom bracket drop figure.

Bottom bracket height

The counterparty to bottom bracket drop is bottom bracket height, the distance from the ground to the centre of the bottom bracket axle. At the extreme, this will impact ground clearance, particularly for a gravel bike which may be ridden over tree roots and uneven terrain. But more pertinently, it’s one of the factors that affects how far you can lean a bike into a turn without the risk of grounding a pedal.

Chainstay length

The chainstay length is the distance between the centre of the bottom bracket and the rear axle. It affects tyre clearance, but also the bike’s ride feel. In general, bike designers will aim to keep the chainstay length as short as possible, while still providing adequate clearance for tyres suitable for the bike’s intended use. You’ll often see bike brands highlighting a performance bike’s short chainstays and snappy handling.

Front centre

The front centre is the distance between the centre of the bike’s bottom bracket and the front wheel axle. It’s a product of a frame’s other dimensions, principally its top tube length, head tube angle, and fork rake.

The front centre affects toe overlap with the front wheel. On larger sized frames, this is generally not an issue, but for smaller frames, toe overlap can be an important constraint affecting bike safety. That’s why smaller frames often have a lower (slacker) head tube angle than larger sized frames for the same bike, as it places the front wheel further forward and helps reduce toe overlap.

This, in turn, affects the smaller bike’s handling, which is why some brands fit their smaller sized road bikes with smaller diameter 650b wheels, to provide more consistent geometry, and hence handling, to larger frames.

Wheelbase

The combination of the front centre and the chainstay length approximates to the bike’s wheelbase (it’s not quite the sum of the two, due to the bottom bracket being lower than the axles, so that the wheelbase is the longest side of a triangle made of the other two measurements).

In general, a longer wheelbase adds stability to a bike’s handling, while a shorter wheelbase makes for a more racy feel.

Standover

Standover is a measurement of the distance from the ground to the top of the top tube at its lowest point. A frame’s standover has to be low enough that you can put both feet on the ground when standing over the bike’s top tube.

It’s another gauge of whether a bike is the correct size for you, although with most bike frames having a sloping top tube, it’s less significant than it used to be.

Stack

The number of variables in a bike frame that can affect fit has led to the use of stack and reach as more reliable and consistent measurements of how a bike will fit.

Stack is the difference in vertical distance between the middle of the bottom bracket and the top of the head tube. It’s unaffected by other elements of a bike’s geometry and a standard measurement quoted in almost all bike geometry charts.

Reach

Reach is the complement of stack. It’s the horizontal distance between the bottom bracket and the centre of the top of the head tube and indicates how stretched out you’ll be as you ride. Generally speaking, a race bike frame will be designed with a longer reach and lower stack, while an endurance bike will have a shorter reach and higher stack.

Reach and stack aren’t measurements that will always allow direct comparisons between bikes though, as considerations such as the handlebar and stem design and sizing will also influence how it feels to ride a bike.

For this reason, you may see stack and reach to the handlebar tops quoted by some brands. Canyon, for example, quotes what it calls stack+ and reach+ for its bike, alongside stack and reach for the frame, to take this into account. Wilier calls the same combination of measurements Accu-Fit.

Now you know what all the measurements on a bike geometry chart mean, you're in great shape to use them to help choose the best road bike or best gravel bike – or indeed any type of bike – to meet your needs.

Paul has been on two wheels since he was in his teens and he's spent much of the time since writing about bikes and the associated tech. He's a road cyclist at heart but his adventurous curiosity means Paul has been riding gravel since well before it was cool, adapting his cyclo-cross bike to ride all-day off-road epics and putting road kit to the ultimate test along the way. Paul has contributed to Cyclingnews' tech coverage for a few years, helping to maintain the freshness of our buying guides and deals content, as well as writing a number of our voucher code pages.