How realistic are Zwift's climbs? We've compared virtual mountains to the real thing

From Box Hill, to Alpe du Zwift, to Mont Ventoux. Just how much like the real thing are Zwift's virtual versions?

With the seasons changing, a lot of us will be swapping the road for indoor training. For a lot of indoor cyclists, Zwift is one of the most popular indoor training platforms that people use with a multitude or virtual worlds and routes. A big part of the appeal of Zwift is the inclusion of virtual famous climbs that we can test ourselves on for personal bests, against our friends, or see how we compare to the fastest riders in the world. But just how realistic are these virtual climbs compared to the real thing? To discover what differences there are between them, we’ve looked in detail at Box Hill, Alpe d'Huez (du Zwift), and Mt Ventoux (Ventop) to see how they compare.

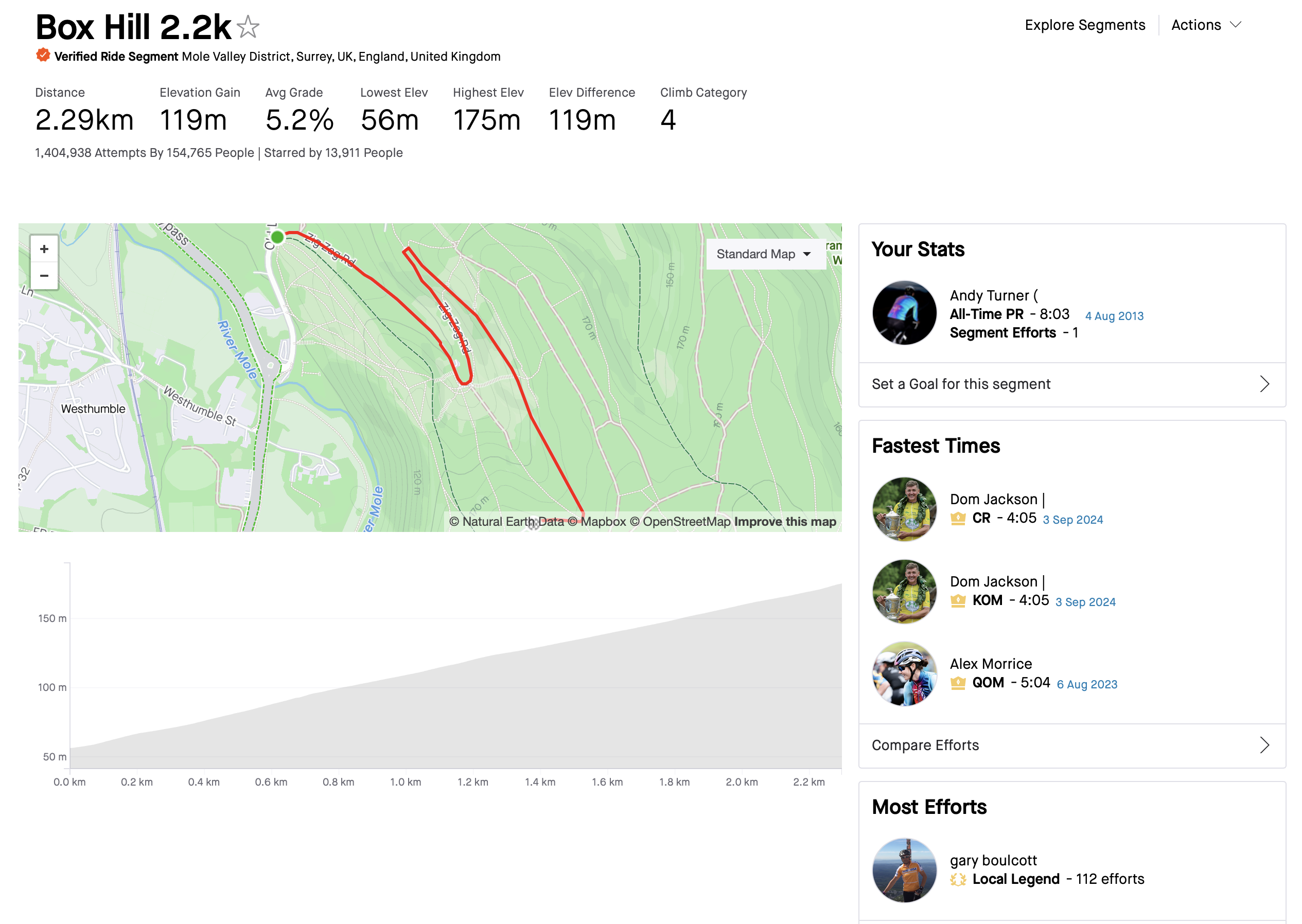

Box Hill

One of the most ridden Strava segments in the entire world (ridden 1,404,940 times by 128,680 people), Box Hill hit international fame with its inclusion in the 2012 London Olympic Games Road race route. Tackled nine times in the men’s race and twice in the women’s, while also being a staple of the Ride London sportive while it did the southern loop. The climb features two switchbacks and an average gradient of 5.2% on the official Strava segment over 2.29km with 119m elevation gain.

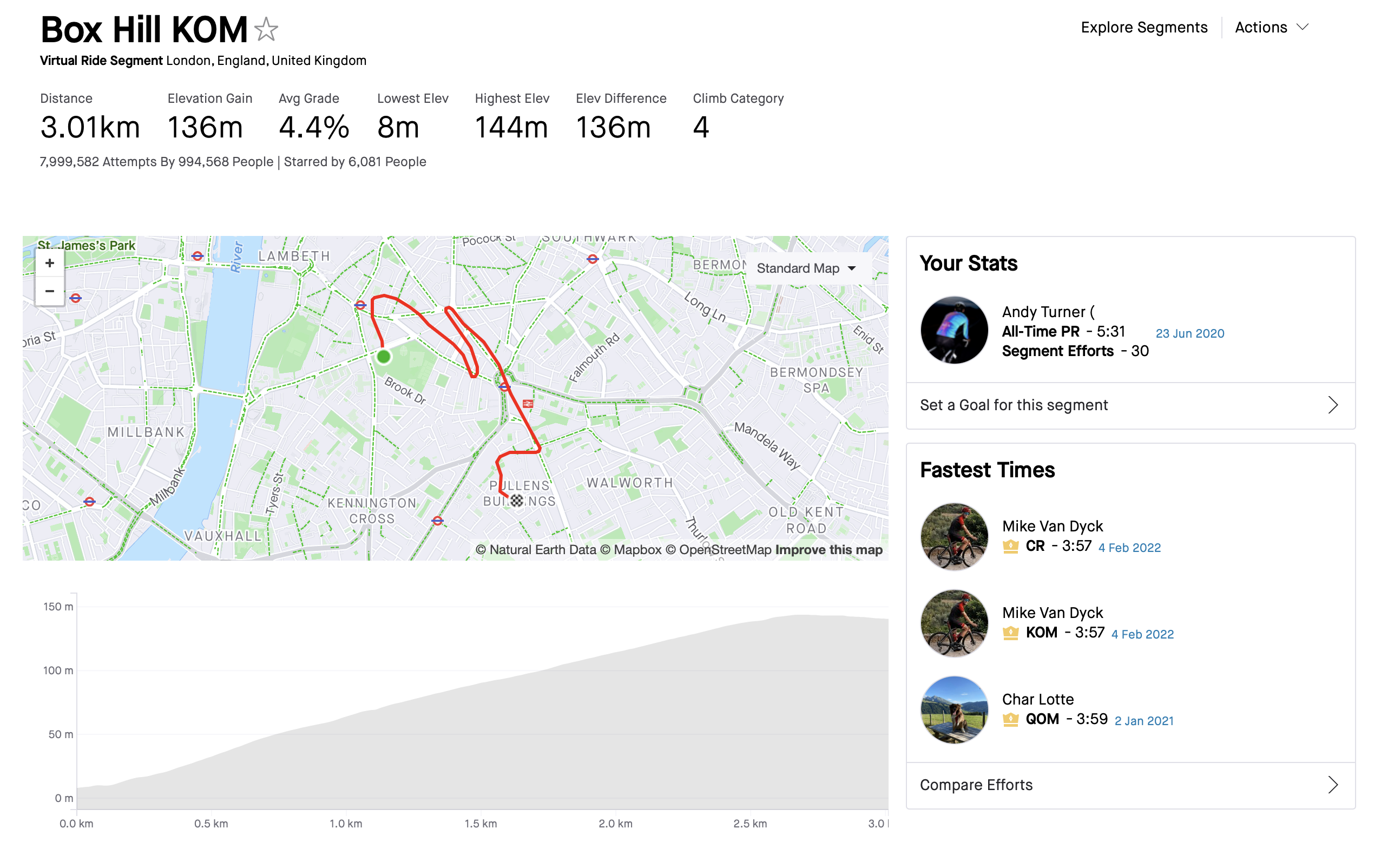

The Verified Zwift segment is ever so slightly different, with the KOM starting around 300m earlier and finishing 500m later giving a total length of 3.01km with 136m elevation gain and 4.4% average gradient. Unfortunately, it’s almost impossible to compare the KOMs between the two, since the Zwift segment appears to have some anomalous results at the top of the leaderboard.

But let’s take some known results - Back in 2020, while I was racing for a UCI team, my best time virtually was 5:31 with a vertical ascent in meters (VAM) of 1477 with a power of 464w and weight of 72kg, giving an average speed of 32.8kph. Funnily enough I did more power on another attempt but the fastest was mid-Erace showing the benefit of virtual drafting.

The current real KOM is held by Dom Jackson who did 4:05, 518w, 1750 VAM, and held 33.7kph average speed. This was done with a team leading out over specific parts of the course and planning every element of the attempt. Even faster genuine times up the Zwift version are not as fast as this, even when accounting for the shorter distance of the real KOM.

Some of this is may be down to weather, as the real climb can be positively impacted by a north-north westerly wind, whereas in the virtual world tailwinds are not a factor. In the virtual world there is no traffic impact though, be that for better or worse, and doesn’t require a fairly grim slog through the city to reach the segment.

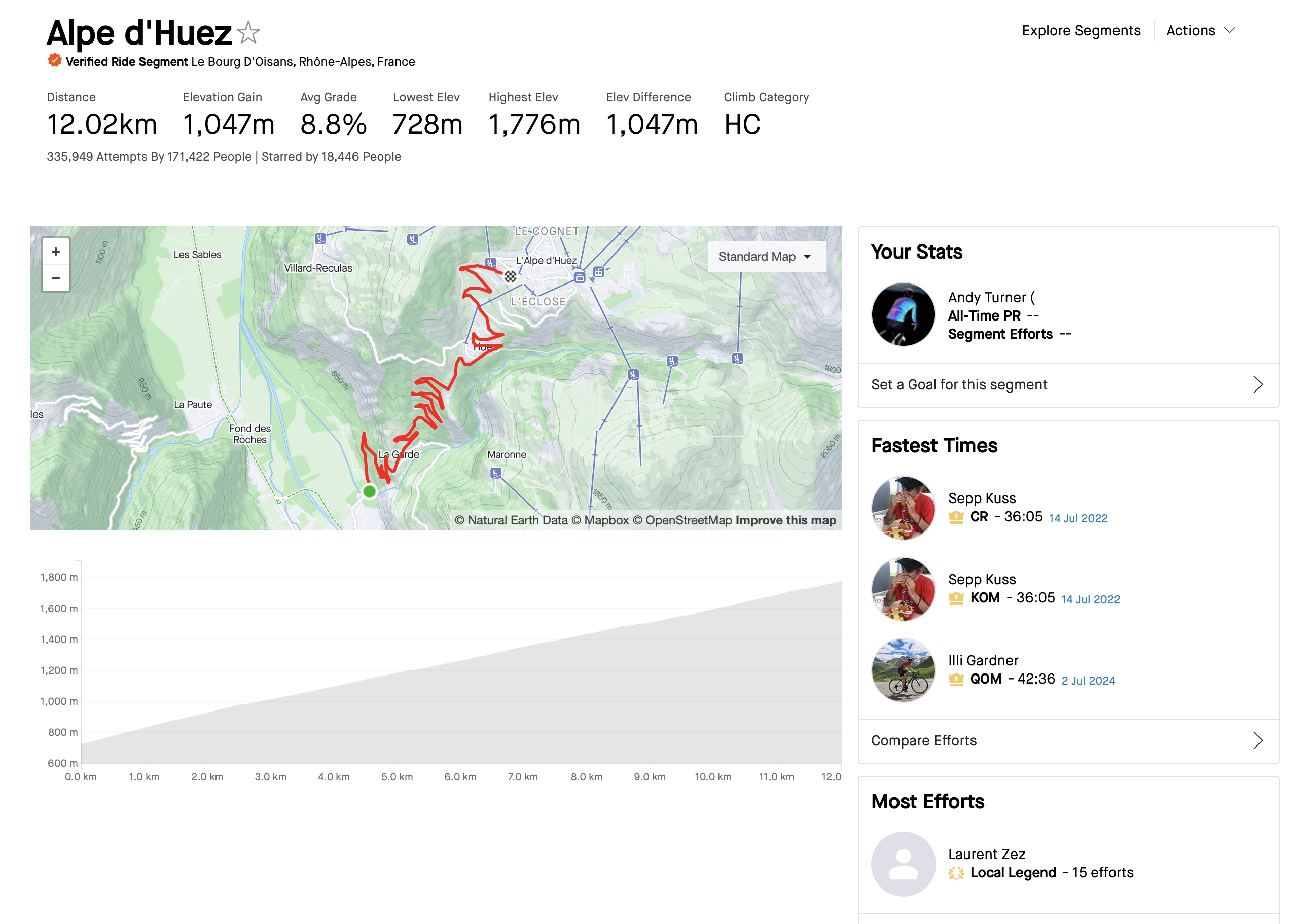

Alpe d’Huez

Another iconic climb, made famous by its inclusion in the 1952 Tour de France, and since then more than 30 reappearances as well as the finale of the 2024 Tour de France Femmes where Kasia Niewiadoma held on to her Yellow Jersey after Demi Vollerings relentless onslaught. The Strava segment has been tackled 335,949 times by 171,422 people and is 12.02km long, has 1047m elevation gain, and an average gradient of 8.8%. Alpe Du Zwift on the other hand is 12.22km, 8.5% gradient, and 1047m elevation gain.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Looking at the two segments, they track very similarly, however the virtual one is rotated about 90 degrees to the left from the starting point. The KOM time for the real climb is held by Sepp Kuss with a time of 36:05 putting out 374w with a VAM of 1741.5 and average speed of 20kph. Again, I set my best time back in 2020, and managed a shocking similar time of 35:33 with 418w at 72kg with an average speed of 20.6km, but sadly only in the virtual world. I know for a fact I am not as fast as Sepp Kuss up climbs and never have been!

Kuss did his effort on stage 12 of the Tour de France, 154.5km into the stage after 4 hours and 31 minutes of racing. It was also 33 degrees average and 38 degrees on the climb. The two efforts are not comparable in any way. I will also add the fastest Zwift segment time is 30:54, more than 5 minutes faster than the fastest world tour riders so it is perhaps safe to say that the digital version is an easier beast to tackle.

It’s also worth considering that the real climb starts at an elevation of 728m and finishes at 1776m, so altitude may have an impact on performance. Additionally it is traditionally a bit of a heat trap so hot temperatures along with the limited airflow of slower speeds can really affect power output and the onset of fatigue. Finally, I did my effort using level mode, where you use the same gear and just sit at a power. No variations, better chain line efficiency, bigger gears so greater inertia, and no variable speed with changes in gradient on switchbacks.

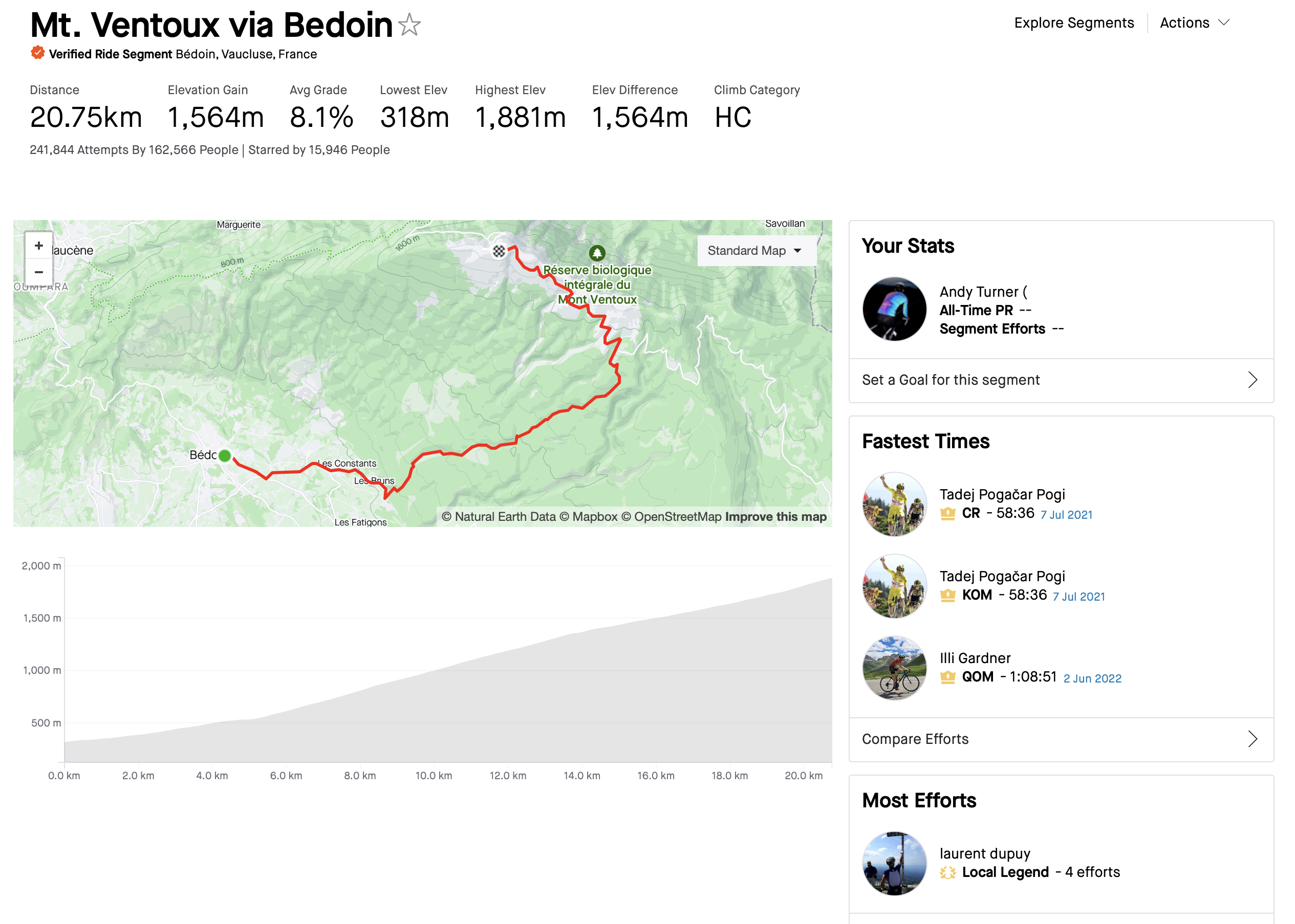

Mt Ventoux

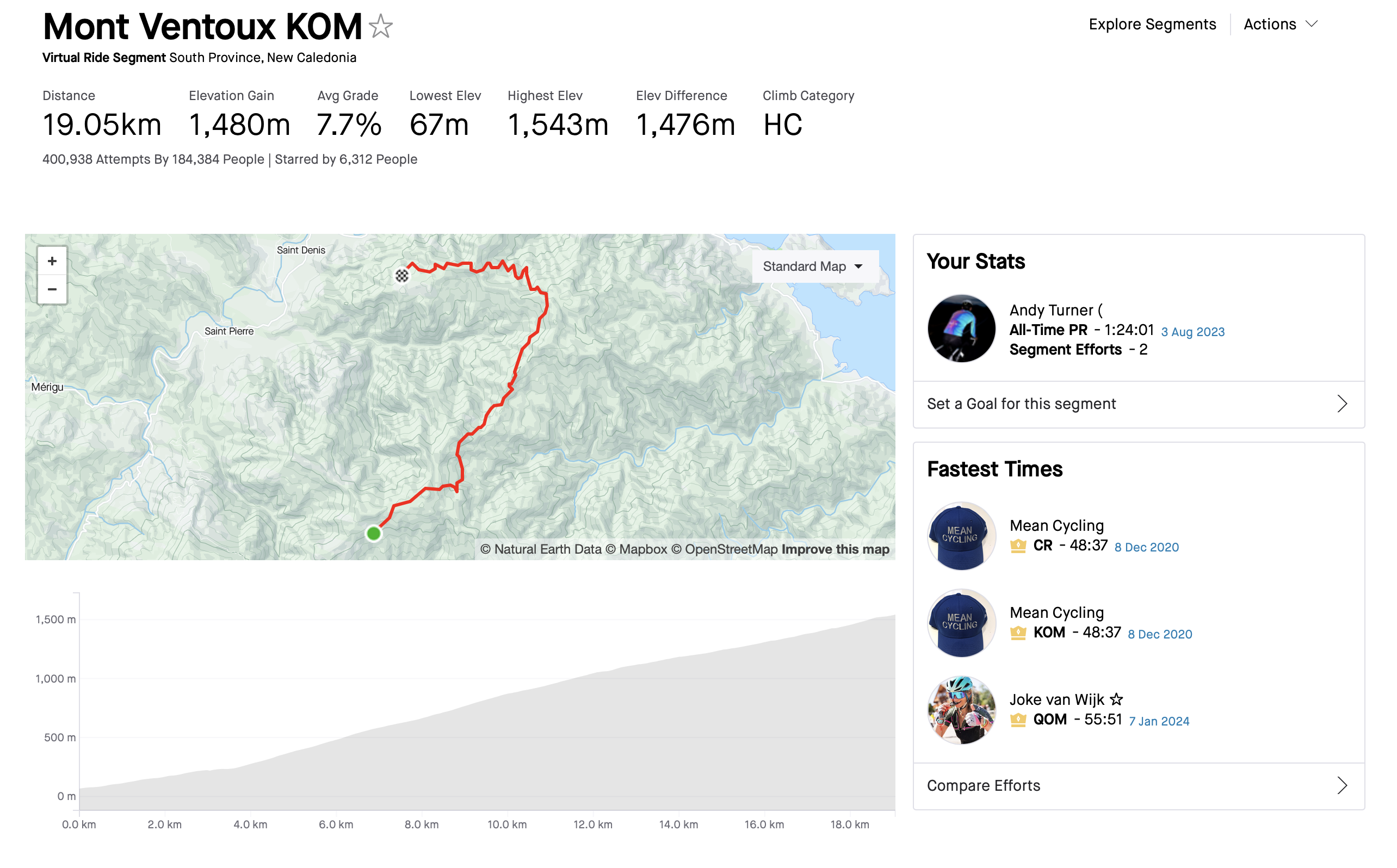

Finally we have a more recent addition to Zwift, and a climb famous for its use in the Tour de France since 1951 with 16 further inclusions, and infamous as the place where Tom Simpson lost his life during the 1967 event. The Zwift version is the climb from Bédion and via Chalet Reynard, as there are three official routes up to the summit of the climb. The real climb has been taken on 241,830 times by 162,565 people. It is 20.75km long, 8.1% average gradient, and climbs 1564m in total. By comparison, the virtual climb is 19.05km long, climbs 1480m at an average grade of 7.7%. The real climb seems to start a little earlier and also finish with the iconic steep right hander past the radio tower.

The real climb has a KOM time of 58:36 set in 2021 by Tadej Pogačar with a speed of 21.3kph and VAM of 1601. Richard Carapaz is second, 12 seconds further back but has power data showing an average power of 346 watts. This time is humbled by the Zwift time up the segment, with the KOM which features a realistic power, heart rate and cadence set by Olympic Rower and former eSports World Champ Jason Osbourne. His time was set in 2020 of 50:40 with an average power of 428 watts, 1748.4 VAM and 22.6kph average speed.

Similar principles apply here to Alpe d’Huez, with Pogačar’s KOM being set on stage 11 of the Tour de France after 4 hours of racing over 155.1km. Whereas the Zwift KOM was set after about 5 minutes of riding. Other factors include the real temperature being 28˚C average and 34˚C peak, as well as a peak altitude of 1881m having an altitude effect.

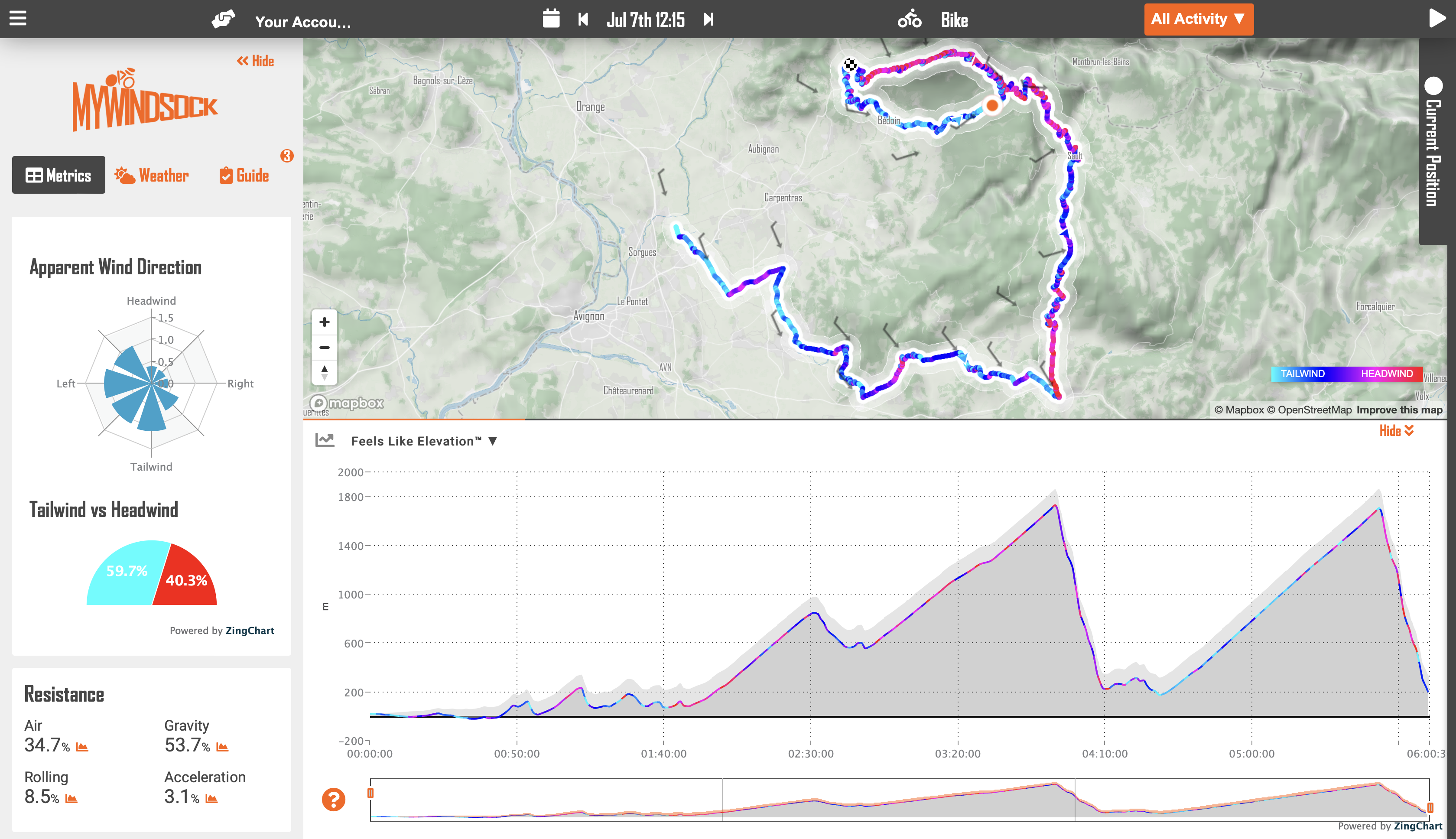

Mont Ventoux is also traditionally a very wind affected climb, with headwinds across the exposed top. Using MyWindSock to analyse the GPX file, we can see that there was actually a tailwind for most of the climb on the longer first section, before the traditional headwind across the top. Yet this time is still obliterated by the virtual assault on the Giant of Provence.

So how alike are they?

As far as the climbs themselves go, Zwift's virtual ones are pretty good imitations of the real deals. The changes in gradient are pretty consistent with the real versions, while the lengths and routes are very similar albeit with some extra run-in or another final twist or turn between the two.

The biggest differences come more from the physics of indoor vs outdoor climbs. The virtual climbs lack the same changes in gradient with result in us having to use our gearing more to maintain optimal power and cadence. Riding indoors also removes the necessity for muscles to work in stabilising us on the bike as we cycle at lower speeds so we don't have the additional fatigue element of this. The impact of smaller gear ratios used when climbing in reality rather than virtually also result in an efficiency loss as well as reduced inertia. Finally, real world heat and altitude affecting performance ceilings whereas indoors neither of those present as much of an issue for most of us with a fan. This also likely contributes to the longer real world climbs having significantly slower KOMS than the virtual ones and why the shorter climbs are more similar between the two.

Another element is when the KOMs were set. It’s no surprise that the only KOM that is more consistent between virtual and real world was set not two weeks into a stage race or after 4 hours of racing. Although the virtual times up the Alpe and Ventoux are impressive, they are not an accurate reflection of World Tour pros being bested by high level eRacers. I think most of us would put money on Pogačar putting minutes into any eRacer's time up Alpe du Zwift with his own fresh legged assault on Alpe d'Huez.

Freelance cycling journalist Andy Turner is a fully qualified sports scientist, cycling coach at ATP Performance, and aerodynamics consultant at Venturi Dynamics. He also spent 3 years racing as a UCI Continental professional and held a British Cycling Elite Race Licence for 7 years. He now enjoys writing fitness and tech related articles, and putting cycling products through their paces for reviews. Predominantly road focussed, he is slowly venturing into the world of gravel too, as many ‘retired’ UCI riders do.

When it comes to cycling equipment, he looks for functionality, a little bit of bling, and ideally aero gains. Style and tradition are secondary, performance is key.

He has raced the Tour of Britain and Volta a Portugal, but nowadays spends his time on the other side of races in the convoy as a DS, coaching riders to race wins themselves, and limiting his riding to Strava hunting, big adventures, and café rides.