How could it come to this? Miguel Indurain's fall from grace

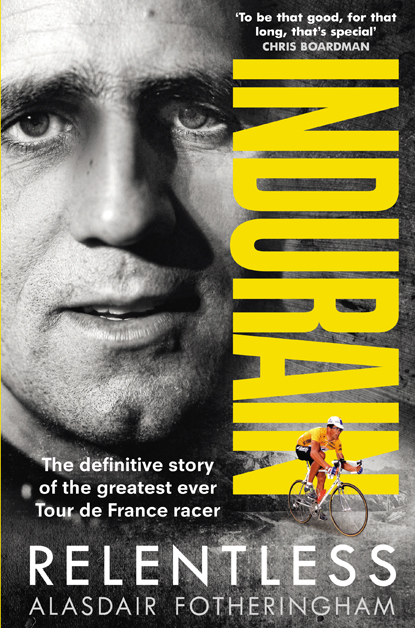

Extract from Alasdair Fotheringham's new book, 'Indurain'

The following is an extract from 'Indurain' by Alasdair Fotheringham (Ebury Press, £14.99)

Back in the day, there used to be an urban legend amongst cycling fans that whoever led the Vuelta a España at the summit of the Lagos de Covadonga climb, deep in the mountains of Asturias, would be declared the outright winner when the race ended in Madrid. But on 20 September 1996, even before stage thirteen of the Vuelta had begun to climb the nineteen-kilometre ascent to Covadonga, it felt as if cycling had lost one of its most crucial battles.

The event that cast an enormous pall over what was in theory the Queen stage of the 1996 Vuelta – and in fact was to cast a shadow over the entire race – unfolded on the difficult ascent of the Fito, the first major climb of the day. A single attack by Tony Rominger, one of the 1990s' most talented Grand Tour racers, began to split the peloton into pieces.

In what was essentially a skirmish before the big battle on the slopes of Covadonga itself, the flurry of controlling moves and accelerations that Rominger's attack produced had a single, devastating consequence: Miguel Indurain, five times winner of the Tour de France and arguably Spain's greatest ever athlete, was dropped.

He was not sweating unduly or swaying over the road as the single line of riders in the peloton drew away from him further up the climb. Indurain had simply run out of energy and rather than go so deep to try to keep up that he then cracked afterwards, he was taking the coldly logical path: eking out whatever scant strength he had left to minimise the damage and limit the gaps.

This, then, was no death-or-glory defeat. Utterly characteristic of his dislike of any kind of histrionic behaviour on or off the bike, Indurain was quietly laying down his arms. Racing in such an economical style was a simple recognition of a simple fact: despite not being ill or injured, his physical condition was such he had lost all chance of winning the Vuelta, and there was absolutely nothing he could do about it.

As the other top favourites put minutes into Indurain in a matter of a few kilometres, it was a curiously dignified last act of the drama and controversy surrounding Indurain's long-awaited participation, after so much Tour success, in the Vuelta a España.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Yet there was no getting away from the fact that Indurain, one of cycling's most brilliantly calculating racers, had become the victim of a gross misinterpretation of his strength. Someone, be it the rider or the team, had made a serious error. In sporting terms, in this race, there was no possible solution.

Indurain's getting dropped from the front group of roughly forty riders occurred exactly as the television coverage of the Vuelta briefly switched channels from the minority TVE2 over to a couple of minutes of live coverage and updates in Spain's prime time early afternoon news on TVE. It was as if fate had decided these crucial moments of Indurain's career should not be confined to viewing by Spain's diehard cycling fans: this was something everybody should witness.

Indurain, who received messages of encouragement from ONCE's directeur sportif Manolo Saiz as he drove past, then had a word with his own Banesto team car as it pulled alongside. The contents of the discussion quickly became clear when he gestured to Marino Alonso – the only Banesto rider to have supported him in all five of his Tour victories and now hovering just ahead of him, waiting for instructions – that he should make his own way to the finish, rather than support his team leader.

As Indurain rode over the top of the climb around five minutes down on Rominger and the rest of the main GC contenders, riders who had earlier been dropped began passing him again on the twisting, wooded descent. Spain's Herminio Díaz Zabala, an ONCE domestique and former Reynolds team-mate, was one of the last to do so, clapping a hand on Indurain's shoulder in sympathy before moving on. It was another recognition that the Indurain–ONCE battle in the Vuelta, it seemed, was over.

This was no rapid surrender, though. Indurain's lengthy solo ride, lasting nearly half an hour before he finally pulled up, became an extended opportunity for fans and the cycling community to contemplate the Tour de France's greatest star going through a sorry, drawn-out and public exit from his country's biggest bike race. If Indurain was physically in good enough shape to stay with the favourites for most of the first two weeks of the race, how on earth had he found himself in this predicament and where was he going from here? How, to put it bluntly, had it all come to this?

For a few moments, the TV cameras lost sight of Indurain when he was caught by the 'grupetto' – the sixty or so non-contenders and sprinters who, with no option of fighting for the win, had dropped off the pace completely by the foot of the Fito. Two months earlier he had been battling for a sixth Tour de France; two days earlier, he had been the strongest opponent of the all-conquering ONCE in the Vuelta. Now, though, he was just making up the numbers.

And suddenly, as Indurain stopped on the roadside, waited for a gap in the race traffic, then pedalled across a hotel forecourt and out of the race itself, he was not even doing that any more.

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.