Hour Kid: Chris Boardman against the clock

How the unbeatable Hour Record marked the beginning of the end

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The following feature forms part of our 'I love the 1990s series,' with Ed Pickering going back to 1996 to recall how Chris Boardman probed his limits as a stage racer, pursuiter and time triallist, culminating in one indelible night in the Manchester velodrome.

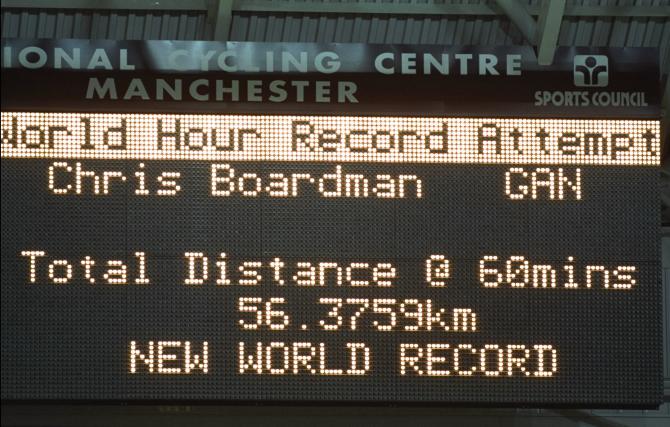

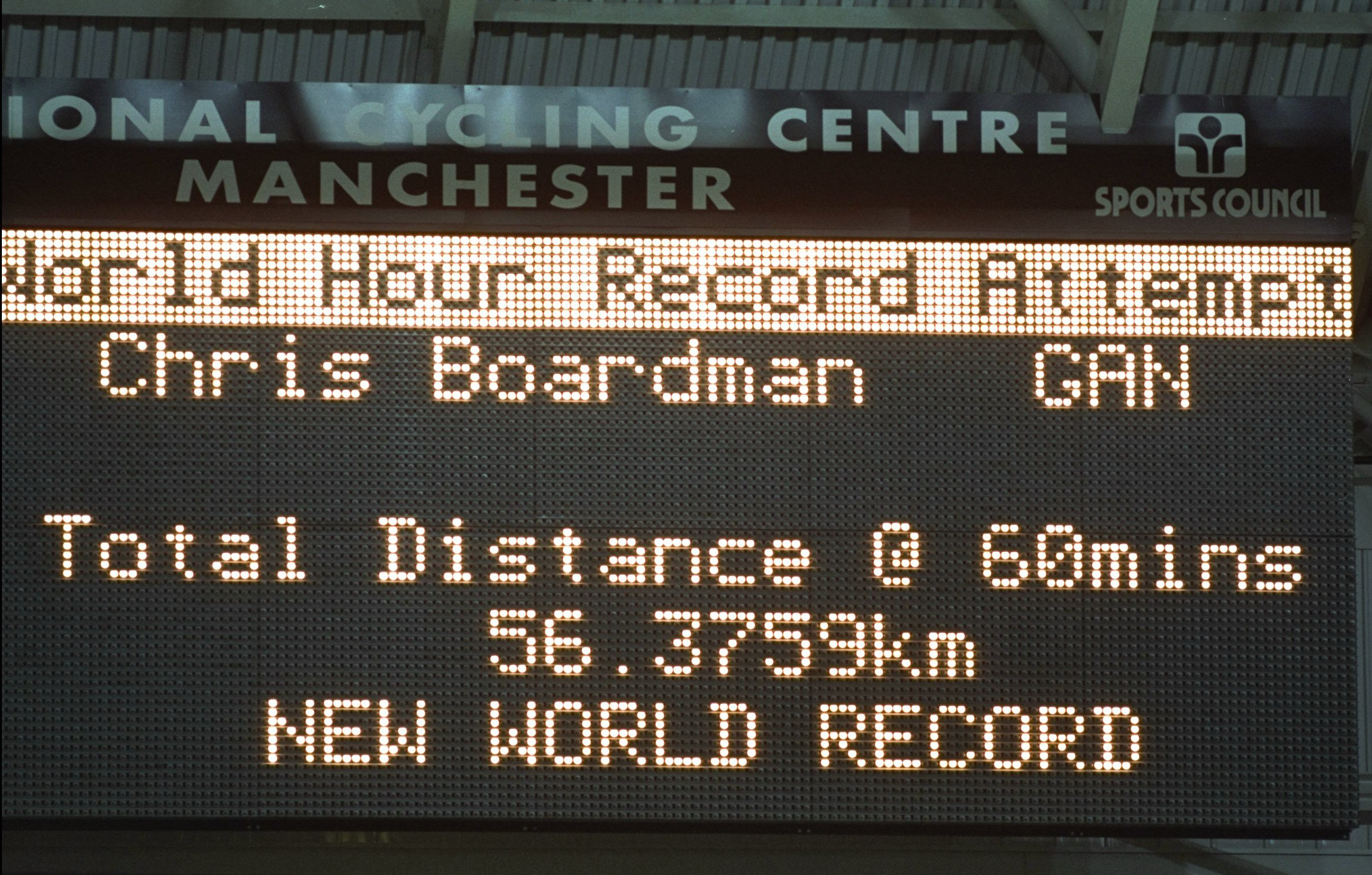

On September 6 1996, Chris Boardman killed the Hour Record. In front of a cheering home crowd at the Manchester velodrome, who were slowly getting accustomed to British cycling success, Boardman rode 56.375 kilometres in 60 minutes. It was more than a kilometre further than the previous record, which had, in turn, been a kilometre and a half further than the one before that.

Nobody has got near that distance since. Nobody even tried until the Union Cycliste International fudged the rules, once in 2000 and then again in 2014, basically resetting the Hour so that people would have a chance. Over 20 years after Boardman's record, which has now been reclassified in the tortured jargon of the UCI as the "best human effort", the Hour Record stands at 54.526 kilometres, courtesy of Bradley Wiggins.

The mid-1990s were a golden age for the Hour. Between 1984 and 1993, Francesco Moser's record, 51.151 kilometres, was seen as untouchable, which is quaint, knowing what we know now. But then, over three years, the record was improved on no fewer than seven times, culminating in Boardman's perfect hour. Graeme Obree broke Moser's record; Boardman broke Obree's record; Obree broke it back. Then the roadies got interested: Miguel Indurain, then Tony Rominger (twice) set new marks in 1994. Finally, Boardman set the definitive record.

The mid-1990s were also turbulent times in cycling's ambivalent relationship with technology and innovation. Obree's records were set using his 'tuck' position, in which he rode with his arms tucked in below his body on an upturned handlebar. The UCI banned that. Boardman's 56-kilometre hour was set using the 'superman' position, also developed by Obree, in which a tri-bar was extended so the arms were straight out in front of the body. The UCI banned that, too.

But there was a lot more to the 1996 Hour than a banned position. Everything Chris Boardman could and couldn't do as a racing cyclist was encapsulated in that one season, and to understand it we have to go back to the beginning of the year and beyond.

Boardman's career trajectory was unusual at the time, though with modifications it became the template for the British Cycling-supported riders who started coming through in the 2000s. He'd been a successful time triallist on the British domestic circuit, winning multiple national titles at a variety of disciplines. Then he started winning road races (generally by attacking and time trialling to the finish – the dark arts of road race tactics weren't Boardman's strength). He won a gold medal in the 1992 Olympic individual pursuit, then set his sights on the hour record, which he first broke in 1993.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The constant through all this was his working relationship with sports scientist Peter Keen. Keen was a champion schoolboy cyclist who'd burned out athletically and then embarked on an academic career with a sports studies degree in Chichester. Keen found his perfect guinea pig in Boardman, who was trainable, very good at feedback and willing to try new ideas.

The 1993 hour record was not just an athletic target and achievement. It was also a marketing exercise to try to help Boardman get a contract with a professional cycling team. In those days, the only realistic way for a British rider to get a professional contract was to go and live in France, Belgium or Italy and claw his way up in a gruelling few years of hard graft, penury and loneliness. Boardman already had two children by this point, and the penury and loneliness didn't appeal, so he and Keen, along with Boardman's agent Pete Woodworth, designed a different way in: set the Hour Record in Bordeaux the day the Tour de France had a stage finish in the city, and impress one or more of the team managers enough to gain the contract.

By setting the Hour Record, Boardman earned a spot on the Gan team. He wore the yellow jersey in the 1994 Tour de France after winning the prologue. So far, his career seemed to be progressing in a linear way, even if the route was unusual. He set targets, and generally, sooner or later, achieved them.

But the next ambition was bigger than time trials and hour records: Boardman targeted the general classification of the Tour de France. Some of the signs were auspicious – he was second overall in the 1995 Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré; quite a way behind Miguel Indurain, but ahead of other notable GC riders, like Richard Virenque. Unfortunately he crashed out of the 1995 Tour on the first day, but that was bad luck (along with pressure, poor judgement and an optimistic belief that he could still win the yellow jersey in spite of riding on a technical course in a torrential rainstorm). He still believed he could be a Tour contender; not necessarily winning it, but top 10.

Which brings us to 1996. The year started very well, with third place overall in Paris-Nice, a result which included a tailwind-assisted 56.199 kilometres per hour average in a 20-kilometre time trial from Antibes to Nice, then a record for a time trial in a professional bike race. Then he won Critérium International. However, the signs that the Tour might be too optimistic a target came at the Dauphiné. He was fifth overall, not bad but he'd shipped five minutes to winner Indurain.

The Tour was a disaster for Boardman. He lost almost thirty minutes on the first mountain stage of the race, a cold and rainy day which finished at Les Arcs. The headlines were all about Miguel Indurain cracking and losing four minutes, but in just one day Boardman's ambition to be a GC rider at the Tour died.

Further hammerings ensued. On the Pamplona stage, Boardman finished 45 minutes down. Keen noticed more encouraging signs towards the end of that Tour, however. Boardman was sixth in the final time trial of the race, a 63.5-kilometre test in St-Emilion, but his final deficit on the GC was an hour and a half. Too much to make up, no matter how hard or well he trained.

There were many reasons for Boardman not being able to string together a challenge over the three weeks of a Grand Tour. His recovery didn't stretch to three-week races, though he could just about hold it together for a week. Boardman has always strenuously denied ever having taken performance-enhancing drugs; anecdotally and as a matter of record, the peloton of 1996 was doping on an industrial level – if Boardman was competing clean against so many doped athletes, it's no wonder he couldn't compete. Thirdly, his Gan manager Roger Legeay identified Boardman as having a deficient 'bagage technique', which is the stock of technical skills a rider must have to handle themselves in a peloton. According to Legeay, Boardman wasn't efficient at riding in a peloton, a hangover from the fact he'd developed as a time triallist and track rider, and it cost significant energy.

Though Boardman was psychologically devastated by his experience in the 1996 Tour, Keen was convinced that the overload he would experience there would have benefits after the race finished. "He'd banked an insane amount of overload against a whole load of people who were doing something else. His form started coming up," Keen said later.

Boardman won a bronze medal in the time trial in the 1996 Olympic Games, then went on to take gold in the world championships individual pursuit at the end of August, using the 'superman' position, in a world record time. Then came the Hour.

"The story of the 56-kilometre ride is incredible form coming off the suffering of being battered in the Tour. Exploiting that position. Good conditions – it was 24 and a half degrees, perfect for him, low air pressure. It was a perfect day, a great crowd, the form of his life,” said Keen. “Is it possible for someone of his shape and weight and training experience to hold 430 watts when you can lie on the bike? It's doable. People occasionally do extraordinary things, and the tragedy of our age is that there is such scepticism now in cycling.”