Henri Desgrange, racism, and the need to re-examine cycling's history

'It's time we parked old myths and opened the door to celebrating Black riders' argues Feargal McKay

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Henri Desgrange was not a racist.

In some circles, that is a controversial statement to make, half a dozen or so well-respected authors of well-received cycling books having claimed over the last five decades that the Father of the Tour de France was a racist. But it is nonetheless true. Henri Desgrange was not a racist.

Desgrange lived in a time when cycling had a racism problem, and cycling's biggest racism problem was to be found in the USA.

In 1894 the League of American Wheelmen (LAW) – cycling's governing body in the US – introduced a 'colour bar', something it had been trying to do annually since 1891. That stopped Black cyclists from joining the LAW but – famously, in the case of Kittie Knox – was not retrospective and so did not disbar anyone who was already a member of the LAW.

The rule also didn't stop riders who were not LAW members from riding in LAW-sanctioned races - a loophole that opened the door to Marshall 'Major' Taylor who, in 1899, became cycling's first Black world champion.

In time, the LAW ceded control of professional racing in America to a breakaway body, the National Cycling Association, an organisation effectively controlled by race organisers and track owners. In 1903, the NCA decided to introduce its own colour bar - a move that prompted Desgrange to speak out against the racism that plagued American cycling.

Desgrange's editorial – published in L'Auto in April 1903 – was brief and to the point, running to a little over 300 words. In it he lamented "the ostracism to which coloured men are subjected in America".

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

It saddened him, he said, "to think that the simple chance of birth can eliminate a man from the struggles of the track, that Americans – whereas we in France have been convinced for a long time that sport has no country or race – still consider themselves dishonoured by the presence beside them in races of muscles as good as theirs and sporting intelligence as keen as well".

In Desgrange's opinion, cycling in France did not have a race problem, and was was more broad-minded than its American counterpart. It may have helped here that cycling in France didn't have many Black riders in the first place, with Hippolyte Figaro – who rode under the mononym Vendredi – one of the few Black riders whose name is still known today.

It is, admittedly, not well known. In 2019, Joseph Areruya was celebrated as the first Black African cyclist to take the start in Paris-Roubaix, an historically accurate claim that still effectively effaced from history one of Figaro's achievements, the Mauritian rider having started – and completed – the first edition of Paris-Roubaix in 1896.

Regardless of the lack of Black cyclists in France, Desgrange believed that French cycling was not racist, writing that "our hands are ready to applaud a good effort, wherever it comes from, we make no distinction between a Negro and a white rider, and the victory seems to us just as beautiful if won by a Jacquelin as by an Ellegaard or a Major Taylor".

All three men named there had won the sprint world championships: the American Major Taylor in 1899; the Frenchman Edmond Jacquelin in 1900; and the Dane Thorvald Ellegaard in 1901 and 1902. All three men were applauded whenever they raced in France, and wherever they raced throughout Europe. Of those three, Taylor is the one most well remembered today, his European racing tours in the first decade of the 20th century having gone down in cycling legend, particularly his first visit in 1901.

Desgrange reminded his readers of how well received Taylor had been: "I imagine that Major Taylor, when he thinks of the indescribable ovations which welcomed him here two years ago, must often be puzzled that, if his homeland is indeed in America, his chosen country and his sporting country are to be found beyond the seas, in Europe, and above all in France."

Taylor's 1901 European racing tour lasted from March through June, with the American star racing on 22 dates in 16 cities spread across Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland. Across 24 individual races Taylor notched up 18 victories. If wins in individual heats are counted – races where the winner was decided over the best of three heats – Taylor's victory tally rises to 42.

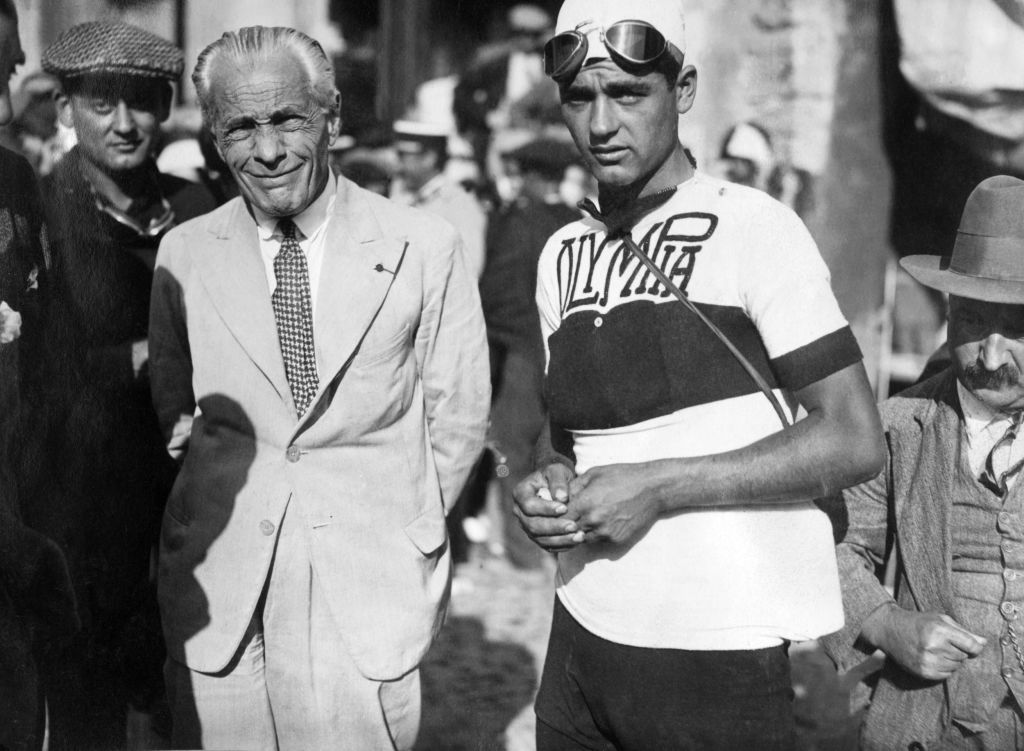

At the heart of that tour were two races between Taylor and Jacquelin.

Pitching the former and reigning world champions against one and other – bringing together two riders who had not previously faced off against each other – brought a record crowd to Desgrange's Parc des Princes on May 16, the little velodrome filled with 20,000 paying punters. Wherever Taylor raced in the spring and early summer of 1901, crowds flocked to see him. As well as being a mini world championships Taylor and Jacquelin's head-to-head was also pitched as Old Europe versus the New World. When Jacquelin won two heats to nil, French cycling fans rejoiced, rushing onto the track and carrying their man shoulder high.

The two met again on May 27 and this time it was Taylor who was victorious, beating Jacquelin two heats to nil. The crowd of 20,000 was simultaneously shocked and awed - shocked to see their hero, Jacquelin, defeated, awed by the fact that Taylor was as good as, better even, than people said he was. The victory celebrations this time were more subdued but still warm. French hands may have been ready to applaud a victory wherever it came from but – understandably – they were more ready to applaud a French victory.

Taylor's victory over Jacquelin in their second meeting is where the claims that Desgrange was a racist arise, with an improbable and evidence-free story circulating that Desgrange paid Taylor his winnings of nearly 40,000 francs – $7,500 – in 10-centime coins, carted away by Taylor in a borrowed wheelbarrow.

Among the many problems with this story is that it just doesn't fit with the way Desgrange and L'Auto wrote about Taylor. Desgrange was an unabashed patriot and he wanted to see French riders do well – he made no secret of the fact that he believed Jacquelin could beat Taylor ahead of their first race, and that he was disappointed to see Jacquelin defeated after their second – but Desgrange celebrated athletic prowess wherever it came from, even when it left French riders defeated.

Throughout the years of Belgian hegemony at the Tour – the years from 1912 through 1923, the years when the Tour was ruled by Philippe Thys, Firmin Lambot, and Léon Scieur – Desgrange took French defeat with grace and lauded the winners of his race. And when it came to track racing – which in those days left road racing in the shade in terms of popularity – Mayor Taylor was, for Desgrange, a benchmark of what a good rider should be. Everybody was measured against Taylor.

After the NCA introduced its colour bar, the number of Black riders in France rose, most notable among the American ex-pats being Woody Headspeth. He'd set an American hour record in 1903 and his arrival in France was warmly welcomed in the pages of L'Auto, with the hope being expressed that he would set a world record for the hour during his time in Paris.

Although he was originally brought to France by one of Desgrange's rivals in the velodrome business – Robert Coquelle, who had taken over the running of the Buffalo velodrome – Headspeth did in time come to race in the Parc des Princes, as well as Desgrange's Vélodrome d'Hiver. There he sometimes found himself paired with another Black rider, Germain Ibron from Martinique.

For the most part we don't really know much about the role played by Black riders in cycling's history in these years. We talk about Major Taylor, yes, and we have some, albeit limited, knowledge of Figaro, Headspeth, Ibron. But riders like AC Spain and F Ivy – more American ex-pats who tried to make it happen in France – have largely been erased from cycling history.

Some of the problem here is that these men raced on the track and cycling history has been reduced to the road and the history of the Tour de France. It's easy for us to imagine that Desgrange was a racist and thus there were no Black riders to talk about.

It's time we parked that myth and opened the door to celebrating the Black riders who helped make track cycling the exciting sport it was. It's time to stop simply retelling the stories previous generations have told and to start examining cycling's history with fresh eyes. It's time to rediscover cycling's past.