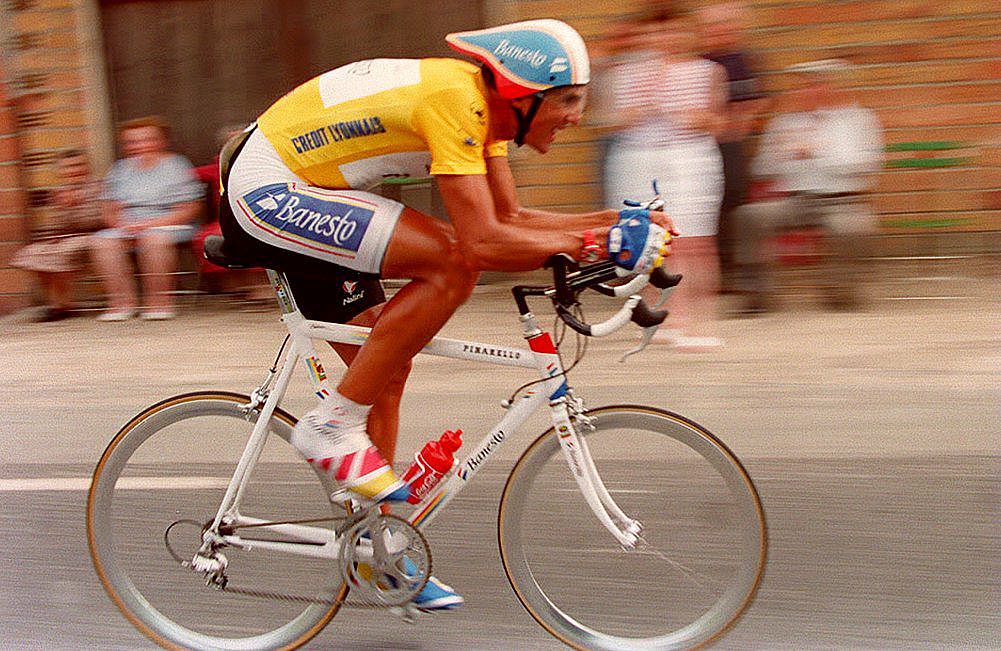

'Happy New Year. When you want, I'll begin' - The moment Miguel Indurain retired

As part of the celebrations of 25 years of Cyclingnews, Alasdair Fotheringham details the end of the Indurain years

"It was like somebody had died," is how former sports journalist Jacinto Vidarte recalls the bleak, funereal, atmosphere that he witnessed Miguel Indurain’s final press conference as a bike racer at a little past 1pm on January 2, 1997.

Rather than a celebration of Indurain’s achievements, crowned by five successive Tour de France victories - the first and to date the only rider to do so - the last page of the last chapter of Indurain’s professional career came down to this: a tall man in his early 30s in a sombre winter coat and dark shirt sitting alone at a table in a hotel conference room in Pamplona, facing a sea of microphones and TV cameras and reading a prepared speech from a single sheet of paper. It took Indurain less than two minutes to tell the world he was no longer part of the sport.

There were no maillot jaunes on the table, no banners or posters behind him, no members of his former Banesto team present, barring press officer Francis Lafargue, watching discretely from among the journalists but without organising interviews.

The recognition and tributes for the man often described as Spain’s greatest ever athlete began with a spontaneous round of applause from the 100 or so journalists in the hotel room after Indurain had finished reading his brief statement. They continued with the hotel fax machine jamming up with messages from well-wishers after a local radio station had broadcast its number earlier that morning. They would flood in for the days and weeks to come.

If newspaper MARCA’s giant tear-shaped headline across its entire front page the next day and its 24-page coverage of Indurain’s retirement summed up the nation’s feelings about Indurain quitting cycling, at the press conference itself there was seemingly no emotion whatsoever from the man himself, still less tears.

Indurain had, he read from his prepared statement, concluded that "being at the maximum level in this sport requires a great deal and every year that goes by that is harder to achieve. I think I have dedicated enough time to cycling and I want to enjoy this as a hobby. I think this is the best decision for me and my family. They are waiting for me, too."

Polite as ever to the last, before he announced he was quitting, Indurain started off his press conference by wishing everybody a "Happy New Year" and then added "When you want, I’ll begin."

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

He answered only one question before heading for the hotel door: was he sad? Indurain, his usual laconic self, replied, "No, I knew this was a day that was coming and it’s finally here."

But how that day happened and how it should have played out could surely not have been different: instead of a dramatic, triumphant look back at his glorious career, Indurain’s exit was painfully low-key.

"There should, at least, have been a homage," Eusebio Unzue, one of Indurain’s two professional directors once told me, "it’s the biggest outstanding debt I have with my team’s past."

But instead, the Banesto management was viewed as having played a key part in his early departure. And at 32, when Indurain still felt he could try for a sixth Tour - as he said in his press conference - it seemed almost unbelievable that the only option for Spain’s top sports star was back through the streets of his home town, Villava, just a stone’s throw away from Pamplona, and out of the sport.

How had it come to this?

Ever since Indurain quit the 1996 Vuelta a España in September at the foot of the Lagos de Covadonga climb - a race he had been forced to take part in by his team, and which constituted the biggest single reason for the rupture with Banesto - the speculation about Indurain’s future had raged across Spain.

"Cycling was far more popular back then that it is now, and together with Nadal, Indurain was the key reference point for Spanish sport," recalls Chema del Olmo, then as now a sports journalist with Spain’s Onda Cero radio station.

"So logically, the general public interest in what he was going to do was very high."

Interest abroad among cycling fans internationally was hardly lower, and in the fledgling years of Cyclingnews, together with Lance Armstrong’s on-going battle against cancer, Indurain was rarely out of the headlines as autumn deepened into winter in Europe.

From October 3rd, when Cyclingnews ran a story saying Banesto Jose Miguel Echavarri confirmed that Abraham Olano - seen by many as Indurain’s potential successor - would sign for them 'to help Indurain win a sixth Tour', through to their two part report on Indurain's retirement itself in early January, what little concrete information there was, along with the huge clouds of rumours that filled the vacuum, were regularly given space in the website

"The usual provisos about the reliability of press reports…" was how Cyclingnews wryly ended one of its umpteen updates.

But if abroad, the lack of a clear picture was painfully palpable, in Spain it was not different: one day it seemed as if Indurain was set on retirement, the next that he would fight back for a sixth Tour, the next that he would quit again. Banesto head director Jose Miguel Echavarri, famously, said he was so concerned about the whole question, he had once gone to Pamplona cathedral to light a candle and plead for some divine intervention, which given the team was nicknamed ‘the little priests squad’, is perhaps not as unusual as it sounds.

But the truth was nobody in this world nor yet the next had a clue what was going on.

Indurain, never the greatest of communicators, did not have anything like a personal press officer, and he gave away precious little in the few interviews he did, except that a decision was still pending - which we all knew, anyway.

At one point, an entire month, while he was on holiday in the Caribbean, went past with no updates whatsoever. The Banesto management knew almost as little as the media, and indeed Indurain reportedly had only two meetings with them, one in early October, another in early November. By December, Echavarri was telling the media, "every time I call his number, I get put straight through to the answer-phone."

"Even now, the relationship between Miguel and his former directors is bad," comments Del Olmo.

"I remember when Banesto had some kind of commemoration for the 25th anniversary of the team, Indurain’s brother and teammate Pruden turned up because at the time he some kind of political position in Pamplona. But Miguel didn’t."

With the benefit of hindsight, signs that all was not well between Indurain and his life-long team stretched back as far as the second half of 1995, just when he was the peak of his career.

Having become the first rider in history to win five Tours de France in a row, rider and team management began to fall out "after they got him to do an attempt on the Hour Record in Colombia," comments Vidarte.

"Miguel had done a long training camp in Colorado, then he’d done the Worlds, and come in for quite a bit of flak from the media for the role he’d played when Abraham Olano won the Worlds." (Indurain had, in fact, played the perfect teammate that day. As the strongest and most closely observed rider in the race, he sat on when Olano attacked late in the day, all but ensuring a Spanish victory. But for the mainstream media, it was viewed as a failure to win.)

"At that point, rather than do the Hour Record, he was exhausted and he just wanted to go home."

The next flashpoint came when Banesto, for reasons that remain unclear, refused to let Indurain’s personal doctor and trainer, Sabino Padilla accompany the team in the 1996 Tour de France, forcing Padilla to hire his own transport for the race. Losing the Tour for the first time in five years did not help. The real division occurred when Indurain raced the Vuelta a España against his wishes and on the team’s orders, and after he abandoned at the foot of the Lagos de Covadonga climb, the rift had widened still further.

Why Indurain took part in the Vuelta that year is the part of the last chapter of Indurain’s career that remains the least clear.

Indurain won’t discuss it, even now, but then again he is loath to discuss most of his career in any kind of detail. Former teammate Pedro Delgado argues that Indurain was a victim of his own lack of assertiveness and should have refused to take part point blank. Eusebio Unzue says his idea was that Indurain would ride the Vuelta as a kind of homage to his countrymen before a possible retirement but admits that with hindsight, it was a major mistake.

As Indurain told MARCA’s Josu Garai back in 1996: "This is the first time in my life somebody’s obliged me do something and I’m not handling it well."

Despite Unzue’s insistence that he backtracked at the last minute and told Indurain it wasn’t necessary to take part, by that point it didn’t matter. Perhaps Indurain considered the mere fact Banesto had tried to force him to race constituted a big enough breach of confidence in itself. Actually taking part in the Vuelta was neither here nor there.

Ironically enough, as Indurain later revealed in his press conference, abandoning his home Grand Tour in his first participation in five years did not lead him to conclude his time as a racer was over. In fact, it had just the opposite effect.

"I couldn’t leave the sport this way," he said in his press release where he admitted he had been thinking of quitting since January.

ONCE enter into the Indurain relationship

At this point, to be precise, on stage 3 of the 1996 Vuelta a España, ONCE, Banesto’s great rivals in Spain entered the relationship.

"The first big moment of communication between us came on the road to Albacete [stage 3] when I drove past Miguel when he and the ONCE riders were in an echelon," Manolo Saiz recounted when he was interviewed for my biography of Indurain.

"I say" ‘Miguel, it’s time’ and he says, ‘you’re right’, and he started working with my boys to keep that echelon clear. If there’s a moment of communication like that in a sporting arena, then there can be a moment of communication for signing."

ONCE’s interest in Miguel Indurain was far more longstanding than one windswept day in Albacete in the autumn of 1996.

Back in 1990, a key member of the ONCE management approached Indurain to see if he was interested in leaving Banesto. His idea was not to sign Indurain as a stage racer but rather as a specialist time triallist. ONCE got wind that Indurain’s contract was up was thanks to Indurain being friends with Basque racer Marino Lejaretta, who had just signed with ONCE that year.

Back in 1990, Indurain thanked the ONCE representative for his interest but politely and firmly said he was fine where he was, not for financial reasons but because, he said later, "my negotiations with Banesto were too far advanced."

That ONCE needed Indurain as much as he needed them in 1996, though, was clear, even if ONCE were widely considered the best, most technologically advanced, team of the decade.

"It wasn’t just that we wanted to be good as a team: in terms of image, that kind of collective strength was the only card we could play given Indurain’s stature,” argued one former team member.

After years with Alex Zülle and Laurent Jalabert as team leaders, signing Indurain would have enabled ONCE to reach out much more effectively to the broader Spanish public. They could not sign Abraham Olano, who was only allowed to break his contract with Mapei that year on condition he signed for 'anybody but ONCE'.

Although reports at the time spoke of five meetings between ONCE and Indurain, in fact there was only ever one, albeit in two segments.

The first was at a private house belonging to a member of the ONCE management near Vitoria, the Basque Country capital, a couple of hours drive away from Indurain’s home in Villava and the second a lengthy dinner in Vitoria itself. Four people were present: Indurain, his doctor and confidante Sabino Padilla, and the two ONCE bosses, Manolo Saiz and Pablo Anton.

Most of the first part of the day-long discussion was about what kind of team support Indurain could expect to have at his disposal in ONCE. Saiz had already vetted and cleared the arrival of Indurain in the team with Laurent Jalabert and Alex Zülle on the flight over to Italy for the last races of the season in Lombardy.

After years of rivalry, the learning process was a two-way street: ONCE’s directors were intrigued, and not a little shocked, to discover that Indurain, held up as an icon of cutting edge technology, had never used a heart rate monitor during training.

The crunch part of the conversation came during the closing part of the dinner: how much Indurain wanted as a salary. When he named his price - roughly the same as what he was earning in Banesto, and later reported, although never confirmed, to be roughly 10 million dollars - the ONCE directors told Indurain for such a large sum, twice their total team budget of the era, that they would have to get clearance from the NGO’s president.

At this point, fate intervened: ONCE were in the midst of boardroom elections and the President at the time told Anton and Saiz that they would have to wait before a decision could be made. The electoral process dragged on into the winter and rather than ringing up Indurain with a concrete offer, the ONCE management’s hands were tied.

So while the media fizzed - particularly after L'Equipe were tipped off by somebody in Banesto about Indurain's meeting with ONCE and ran a story saying Indurain would switch squads for €10 million, and with the ONCE electoral campaign dragging on interminably, Indurain’s career was effectively on hold and quite possibly over. But nobody had all the pieces of the jigsaw, except for Indurain, and he was waiting for an offer that never came.

The confusion was such that Olano says that when he signed for Banesto that autumn, he was under the impression that he would be racing as Indurain’s lieutenant in the Tour and leading the team in other races. Instead, suddenly he found himself having to fill Indurain’s shoes in Banesto: as he once told me, showing his considerable gift for understatement - something he has in common with Indurain - "that’s not the same thing."

"Another problem was that Indurain had no agent," observes Vidarte. "He had no one to advise him, apart from Padilla, and it made it very hard for rival teams to talk to him."

When the director of another team, Polti’s Gianluigi Stanga, made an offer to Indurain that autumn, his only way of getting it to the rider in question was by sending a fax to the Indurain household phone number and hoping somebody would notice. They did, but showed no interest. An offer from Kelme, almost certainly designed purely as a publicity stunt, never even got that far, nor did one from Lampre.

It was also very difficult to know how interested Indurain really was in continuing. Rather than run around looking for teams in the autumn of 1996, he had headed off on holiday for a month. He had already opted for a single year’s contract rather than the usual two in 1996 - something which Banesto’s management later tried to exploit as evidence he was already thinking of retirement.

However, after the Vuelta, Indurain had seemingly changed his mind. And at the same time, his meeting with ONCE after years of complete loyalty to Banesto would suggest he wanted to continue. That provided fresh fuel for another chapter of the seemingly eternal Banesto-ONCE war.

Jose Miguel Echavarri, never short of a choice phrase, sneered that ONCE had gone "looking to buy angulas" - an exceptionally prized and expensive type of fish in Spain – "without any money in their pockets."

Yet if ONCE were at least eying the product inside the fishmongers, Echavarri was outside with his nose stuck to the shop window, as was underlined at a prize giving ceremony for MARCA in December. Indurain and Echavarri were both invited and rider and director sat on different sides of the auditorium as far away as possible from each other.

Indeed, signing for ONCE continued to be the only way of Indurain continuing his career, and in the final days before Indurain retired, it would be raised in the media as a serious possible alternative. Yet ONCE were stymied by the lack of money, and no other team seemed able to access Indurain.

By the time the curtain fell on Indurain's career on January 2nd, the seemingly unthinkable had happened: the most successful rider of his generation, the man who became a symbol of Spain’s success at modernizing itself, the person who nobody had (or indeed has) a bad word to say about, was out of the sport.

At the end of the day, quitting was the only option - and Lance Armstrong’s subsequent suggestion to Indurain that he make a comeback in his team, never got off the ground either. But that, in any case, is another story.

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.