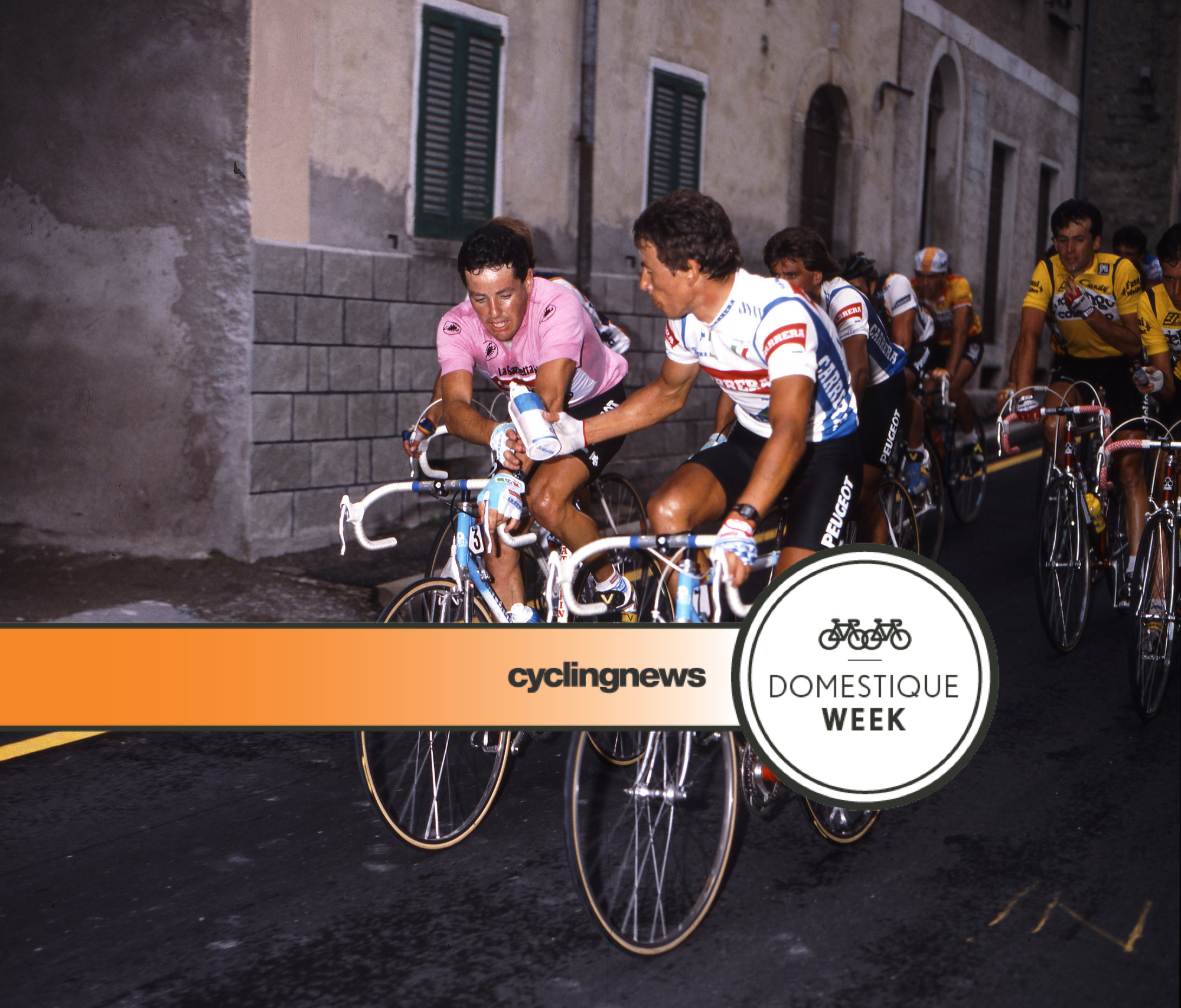

Gotta serve somebody: Eddy Schepers and the domestique's calling

Caught between Roche and Visentini at the 1987 Giro d'Italia

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Most domestiques were once future champions. Eddy Schepers certainly was. In his final year as an amateur in 1977, he started the summer with victory at the prestigious Giro delle Regioni and finished it by beating Johan van der Velde and Roberto Visentini to become the first Belgian winner of the Tour de l'Avenir.

In doing so, Schepers became the first man to achieve a Franco-Italian double, only ever replicated by Sergei Sukhoruchenkov – the Soviet rider heralded as the Eddy Merckx of the Eastern Bloc. The following season, Schepers had a brief chance to measure himself against 'The Cannibal' in person, turning professional at C&A, where Merckx spent the final, guttering weeks of his career before the flame was quenched.

Schepers was never great during his stints at C&A and DAF Trucks, but he was frequently very good, placing fifth at Liège-Bastogne-Liège, second at the Belgian championships and 15th in his debut Tour de France in 1979. A fine climber, he seemed to operate between the lines: too talented to be a mere water carrier but not quite at the level required to lead.

He moved on to ride for the Italian Gis-Gelati squad in 1982 – the interregnum season between Giuseppe Saronni's departure and Francesco Moser’s arrival – and placed 11th in his first Giro d'Italia. He would toggle between Italian and Belgian teams in the years that followed, and consistency was his byword: 12th at the 1983 Giro with Perlav–Eurosoap, 12th again a year later with Dromedario, and then 14th in the 1985 Tour de France with Lotto.

By then, Schepers was on the cusp of his 30th birthday and had long since realised that he had reached the limits of what he could himself achieve in the Grand Tours. If he wanted to prolong his career, he needed to devote himself to a leader. Indeed, had his spell at Gis coincided with Saronni or Moser, he might already have done so.

"When I rode for Lotto, I did quite a good Tour for my capacities, but I felt I'd reached my own limits as a rider in the Grand Tours," Schepers said in an interview for The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation. "Fourteenth place in the Tour de France isn't bad but a sponsor expects more, so that's why I was ready to take on the role of a domestique for a big rider. I saw that I could make a good career that way."

The opportunity presented itself at the end of that season. When Stephen Roche, third at the 1985 Tour, swapped La Redoute for Carrera, he came without the entourage normally expected of a Grand Tour contender. Only his mechanic and confidant Patrick Valcke followed him, and so Carrera manager Davide Boifava set about hiring domestiques to put around Roche.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Schepers was the right fit, in every sense. As well as his gifts as a climber and a tactician, the native of Belgium's sugar production capital of Tienen had experience of Italian teams and could serve as an ad hoc translator for Roche, with whom he conversed in French.

"He was ideal for bike exchanges, too, because he was my size," said Roche. Nobody said the domestique's job is glamorous.

"I remember I'd seen in the papers that Stephen Roche was going to Carrera. I didn't know him well at the time, but I took note of that," Schepers said. "A short time later, I got a phone call from Mr. Boifava and he asked me: 'Eddy, are you still free to come and ride for us next year?'"

It was the call he had been waiting for his entire career.

Roche

While Schepers was primed for duty, Roche was not yet ready to lead. He oscillated between good and bad seasons in the 1980s, and having made the podium of the Tour in 1985, he endured a wretched, winless campaign in 1986 as he struggled with the lingering effects of a knee injury sustained in a crash on the track at Bercy the previous winter.

Though Schepers had ostensibly been signed to ride in Roche's service, that task wasn't specified in the wording of his contract with Carrera. As a gregario, Schepers had to serve somebody, and there was no shortage of potential leaders. At the Giro, Schepers was one of the key men in Roberto Visentini's overall victory, while at the Tour, he helped Urs Zimmerman to third overall and Guido Bontempi to a brace of sprint stage wins.

Carrera's success that summer underscored Schepers' wisdom in committing to the life of the domestique. Placing on the fringes of the top 10 in a Grand Tour had offered some personal satisfaction, but working for the overall winner delivered the more tangible reward of cold, hard cash: six stage wins, overall victory and the points classification at the Giro added up to a hefty pool of prize money to be doled out among the team.

"It was a good season, in spite of Stephen's injury," Schepers said.

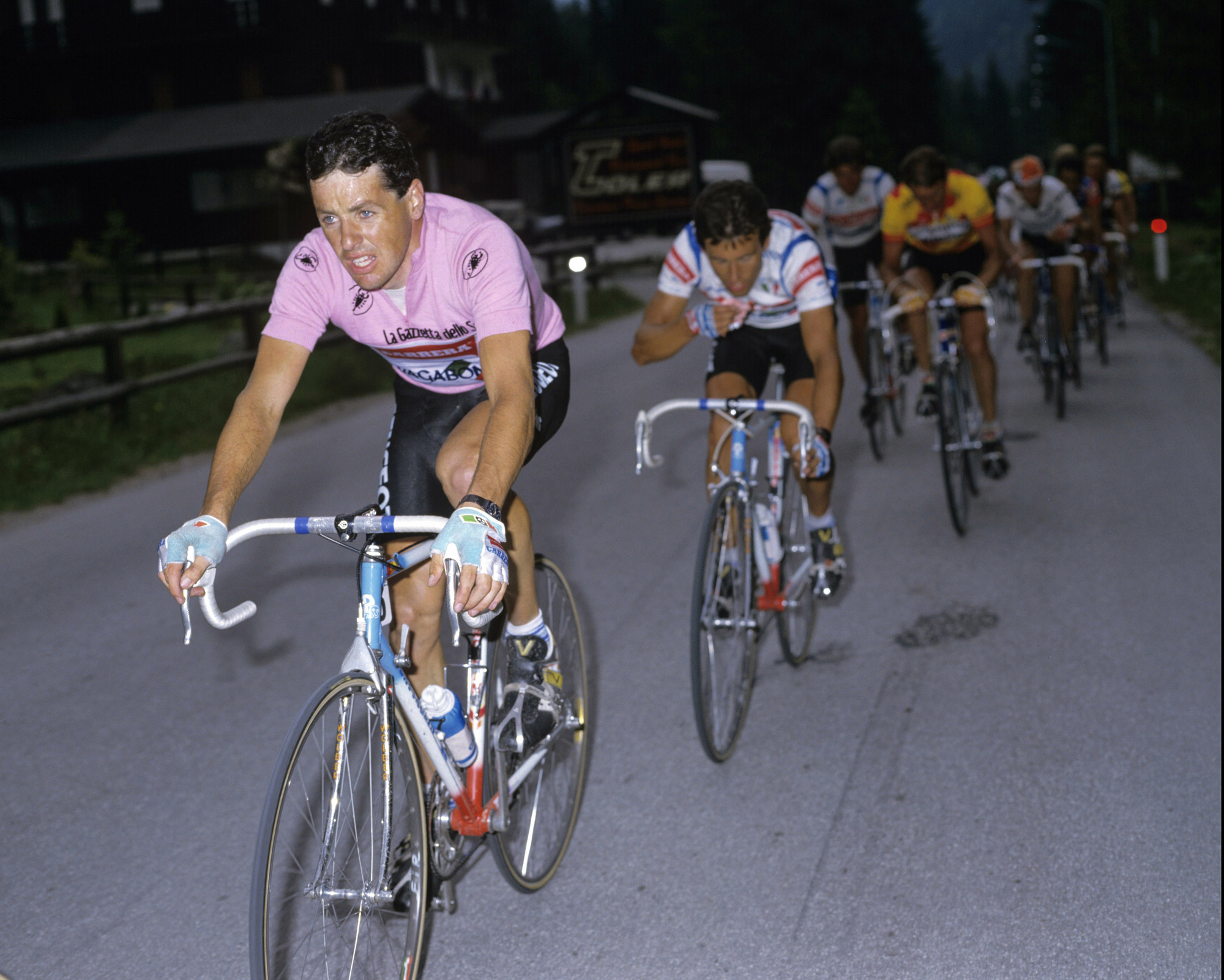

He would have a better one in 1987, even if the creative tensions inside Carrera would reach breaking point during a most tumultuous Giro. The opening phase of the campaign, by contrast, was as unruffled as Roche's famously elegant pedal stroke, which Schepers could see had been restored to its previously serene state when Carrera gathered for their January training camp.

"We were always roommates, always together at all the races and training camps," Schepers said. "I saw that he was heading off for extra work in the afternoon, and when I'd ride behind him, it was like riding behind a motorbike."

With his contract expiring at year's end, Roche was eager to win early and often in 1987 to secure his future. He began with victory at the Volta a la Comunitat Valenciana, and only an untimely puncture denied him the spoils at Paris-Nice. After frittering away Liège-Bastogne-Liège victory, Roche warmed up for the Giro with an emphatic win at the Tour de Romandie.

Although Visentini was the defending champion, Boifava decreed that Carrera would line up for the corsa rosa with two leaders, although, initially at least, there was no place for Schepers. Boifava had told Schepers he wanted to keep him fresh for July, but with Carrera expected to dominate the Giro, the domestique was reluctant to miss out on the season's most lucrative payday. After proving his loyalty to Roche in the early season, he asked his leader to return the favour.

"I needed to make money, and, in that period, the prize money was better at the Giro than at the Tour, especially if you were riding for a good team," Schepers explained. "So I said, 'Listen, I ride for you all year, Stephen, but now there's a situation where I can really earn some money and I'm not going to be able to participate. Can you do anything about that?'"

Roche already knew Schepers' qualities as a rider but must also have realised the value of a willing ally on a team where his injury-blighted debut season had seen him earn the disparaging moniker of 'the phantom rider'. Roche needed all the friends he could get, and he insisted on Schepers' selection.

The Carrera prize kitty had three sizeable deposits in the opening four days, as Visentini and Roche traded early blows by winning the short time trials in San Remo – the Irishman triumphed on the cronodiscesa off the Poggio – before leading their squad to victory in the team time trial at Camaiore.

On the first summit finish at Monte Terminillo, where Roche was already in pink, Schepers had a chance to add to that tally when he found himself in the winning break with Jean-Claude Bagot, but he elected to hand victory to the Frenchman in return for an assurance that his Fagor team would help Carrera – and Roche, specifically – later in the race. It may or may not have been a coincidence that Roche had been in talks with Bagot's team since the previous month's Tour of the Basque Country.

"Stephen was isolated that day; I was the only one with him," Schepers said. "I couldn't ride for him on the flat if he needed me in the mountains, too, so we chose a bit of a collaboration with the Fagor team there. They did some work for us after that."

The assumption, of course, was that Roche would still be in pink after the pivotal San Marino time trial on stage 13, but the Dubliner turned in a subdued showing in the uphill test. He conceded almost three minutes to a sparkling Visentini, who now led him in the overall standings by 2:42. The question of Carrera leadership, which had so fascinated since the race began, seemed to have been decisively resolved.

Sappada and all that

In Roche's telling, the ambush at Sappada has an almost Ocean’s Eleven quality, planned and supported by his team within a team of Schepers and Valcke. He has even credited Schepers with proposing the sinuous stage through the Carnic Prealps rather than the Dolomite tappone as the day to test Visentini's mettle. Three decades on, and perhaps still mindful that his contract was with Carrera and not with Roche, Schepers insisted that the acceleration on the descent of the Forcella di Monte Rest was entirely down to the Irishman's own invention.

"No, nobody knew he was going to do that – not even me. He hadn't talked about it the night before," Schepers said of the move that saw Roche bridge up to the leaders, Bagot and Ennio Salvador, with 80km still to race. "And it wasn't bad for the team, because it was now up to the other teams and leaders to ride at the front of the peloton."

Roche's defiant dismissal of directeurs sportifs Boifava and Sandro Quintarelli's entreaties to stop riding has entered Giro lore, but Schepers' own dilemma is often overlooked. The Carrera team were instructed to chase on behalf of Visentini, but Schepers was the one rider who declined to pursue a teammate.

"The management team reminded us that Visentini was the patron and told us to ride behind Stephen, but I didn't ride on the front of the peloton," said Schepers.

No matter, Carrera's pacemaking brought the bunch to within touching distance of the break ahead of the Valcalda, and Visentini and Schepers were each part of the large group that bridged across to Roche before the final climb of Cima Sappada. Visentini, flustered by what he felt was Carrera's tardiness in pursuing Roche, began to struggle as soon as the gradient bit. Boifava drove up alongside the front group and ordered Schepers to drop back immediately to help the floundering maglia rosa limit his losses.

As a rider on Carrera's 1987 roster, Schepers had no option but to comply. As a rider looking for a contract for 1988, he was compelled to explore his options. The role of the domestique is romanticised as a vocation but it is lived unapologetically as a profession. With the 1987 Giro in the balance, Schepers negotiated his passage to Fagor the following year.

"I was up with Stephen at that stage, and I said to him, 'Look, I don't have much of a choice here. I'm going to have to sit up and wait for Visentini unless… Well, if I help you, I'll need to be certain that we'll be riding together next season,'" Schepers said. "And Stephen said, 'Listen, Eddy. Stay here.' So I stayed with him, and that's where our friendship became even closer."

Roche took the maglia rosa that afternoon in Sappada – "If he hadn't, I'm certain they'd have sent the two of us home," said Schepers – and the rest of the team, Visentini apart, quickly realised that, although the leader had changed, the prize (money) remained in sight.

"I remember Davide Cassani came to the room afterwards to talk to Stephen and explain things," Schepers said. "Not everybody could do what I did and reject Boifava's orders. It was more difficult for the Italian riders to do it, because they were part of the organisation."

The next day, it fell upon Schepers to guide Roche through the sea of tifosi in the Dolomites, and although Visentini never claimed the kind of support enjoyed by Moser or Saronni, Schepers recalled his anxiety on the Marmolada.

"It really felt like it was la guerra," he said, although Roche survived the day and went on to seal victory.

After the Giro concluded at Saint-Vincent, Roche, Schepers and Valcke didn't linger to celebrate with the rest of the Carrera team.

"We left that night by car for Stephen's house in Paris, without even knowing whether we'd be able to ride the Tour,” said Schepers. In the days after the Giro, they even explored the possibility of changing teams before the Tour, but both Roche and Schepers were included in the Carrera squad that lined up in Berlin for the Grand Départ.

With just one stated leader, the Carrera squad in France was a more cohesive unit – "It was a very strong team, and a bit like the Team Sky [Ineos] of today" – but Schepers remained a pivotal part of Roche's entourage on and off the bike. He was the first man journalists encountered when they visited Roche's hotel room in pursuit of scoops about the make-up of Fagor's 1988 roster, and he was the last man to stay with his leader in the mountains.

Roche's fightback at La Plagne is the defining image of his 1987 Tour victory, but no less pivotal was his attack on the descent of the Joux Plane the next day, which had been teed up by Schepers.

"I think that was the best stage I ever did in the Tour," he said.

It's a mere footnote in the tale of Roche's eventual Giro-Tour double, but a domestique's duty lies in the detail.

Patron

Economics aside, Fagor was a disaster. Schepers, metronomic in his regularity, was one of the few riders who succeeded in performing to his usual level on a team riven by chaos. The polemics are too numerous to list, but the confusion over the role of lead directeur sportif was indicative of the wider disarray. Pierre Bazzo, sidelined to make way for Valcke, replaced him midway through the 1988 season. Valcke was then reinstated at the start of 1989 but Bazzo remained in place, while Ramon Mendiburu was brought in to oversee operations.

Roche, beset by the recurrence of his knee injury, barely rode in the rainbow jersey of world champion in 1988. In his absence, Schepers weighed in with ninth overall at the Vuelta a España before returning to his leader's service the following year, although Roche's roommate was new arrival and childhood friend Paul Kimmage.

"I'd probably have been pissed off if I was Schepers," Kimmage recalled in 2016. "I thought he was a smashing guy."

If Schepers felt slighted, it didn't show. He helped Roche to ninth overall at the 1989 Giro and was by his side to nurse him to the finish when he was distanced irretrievably on the first day in the Pyrenees on that year's Tour. Roche abandoned that night, and his loyal lieutenants Kimmage and Schepers would leave the race, essentially in sympathy, within two days.

By then, Valcke's position at Fagor was untenable, and he and Roche prepared an exit strategy, joining Belgian squad Histor. Schepers, who felt Roche had been ill-advised to leave a team as well-drilled as Carrera in the first place, was now bemused by how he had allowed his relationship with a sponsor as generous as Fagor to unravel.

"It's the patron who pays and if the patron lays down conditions, you have to accept them," said Schepers. "We weren't on the same line. Patrick and Stephen wanted to leave the team, but their new team wasn't on the same level. Fagor was a capable sponsor; there was no problem with money. I think Stephen took decisions with Patrick that he might not have taken if he'd been acting for himself, alone."

Schepers opted to go his own way in 1990, signing for Tulip before calling time on his career after that year's Vuelta. Roche saw reproach in that decision, and their relationship suffered as a result. But the best domestiques aren't yes men. In time, Roche came to realise that, too.

"We parted company and that caused quite a bit of strain between us, but we made up later on," Schepers said. "We'd consider each other as friends for life. We don't speak every day, or even that often, but when we do see each other, we pick up where we left off."

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.