Giving amateurs a flavour of the Tour

L'Etape du Tour gives amateur cyclists a taste of what the pros experience in a mountainous stage of...

L'Etape du Tour feature, Gap - L'Alpe d'Huez, part 1

L'Etape du Tour gives amateur cyclists a taste of what the pros experience in a mountainous stage of the Tour. The 2006 L'Etape mirrored stage 15 of the Tour, a 191 km exhausting ride through the Alps culminating with the 21 numbered corners of l'Alpe d'Huez. Mark Sharon was one of the 8500 riders who fought off fierce competition just to get a start. He gives an account of what it's like to compete in a mountainous Tour stage in part one of his three-part story.

Velo Magazine served up its 14th edition of the Etape du Tour this year with one of toughest in a history of some very tough events: Stage 15 of the 2006 Tour de France - a 191.4 km test of climbing and endurance starting at Gap and culminating with the strength sapping grind up l'Alpe du Huez with its 21 numbered corners.

Despite a profile that would keep a sane man in the bar, the competition to get into this years' event was as fierce as ever. It is not difficult to see why. With just a couple of exceptions, L'Etape du Tour has been consistently faithful to the concept of giving amateurs a genuine flavour of the world of a professional Tour rider.With its first edition in 1993, Velo Magazine put its marker down as it meant to go on. That year's edition took what is by today's standards a tiny field of 1705 riders 190 km between Tarbes and Pau, crossing the Col du Tourmalet, Col du Soulor and Col d'Aubisque. First place was taken by one Christophe Rinero - at the time of writing in 26th place on General Classification of the 2006 Tour de France.

The 2006 Edition

While getting into L'Etape du Tour is a major part of the challenge, finishing is a completely different matter. You may have eaten like a king, rested in a chateau, flown to the start line in a helicopter (oh, yes - there are one or two riders who do just that). You may have had the best training help, and be riding the most expensive bike one can buy but once that gun goes off you are on your own - all

8500 of you.The 2006 edition was always going to be tough - three big climbs and 191.4 km of high altitude alpine road (statistically 188.4 km, but you have to add on the opening 3km neutralized zone for good measure). First up, the legendary Col D'Izoard (2360 m) is not reached until almost the half-way mark. After a fast descent to Briançon, the Col du Lautaret, (2057 m) lay a further 30km grind further on. From there the longest descent of the day at 38 km takes the race to the lowest point of the day at Bourg d'Oisans. It is not over yet - it is just a matter of climbing the infamous (another adjective ticked off) Alpe d'Huez - 1200 m of ascent over 15 km. You work out the average gradient.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The biggest variable of all was weather. Except by the day of the race it was a certainty. All the forecasts pointed to the day being typical of the three weeks before - clear skies, and a high of 34 degrees centigrade. Out on the open road that temperature was sure to be a lot higher. It would take more than factor 35 sunscreen to cope.Over the weekend Gap had done a damn fine job of welcoming us to the Alps. The start village was bigger than ever and jammed packed with stands, coffee shops and bars, a massive screen for watching the tour and even a climbing wall, which the kids dominated. We cyclists are by nature over-analytical and both the information boards and the concessions were crowded with riders worried whether they would find their place at the start, their loved ones at the finish or whether a new pair of wheels would shave enough milliseconds off their time to be worth the 700 euros. Personally, I had enough time battling a tyre change the night before to risk swapping even a bolt at this stage.

On race day the start area was the usual melee. Riders dropping off bags and queuing for a pee… or not. I doubt the bushes along the main straight have much chance of recovering form the urinary assault of 8500 desperate bladders. The bag drop-off was fun too. Everyone had been given a rucksack with their dossard (French for race number), and now there were hundreds of identical bags piled up in the luggage trucks. One lost tag and you would never see your underpants and shoes again.Nothing prepares you for the Etape like the start itself. I was starting the race with Maurice Chabot, Luc Humbert and John Reed, who I would be lucky to see again once the race started. We would all be concentrating too much on our own survival to keep track of each other. The final count-down culminated in a crescendo of clack-clack-clack as thousands of feet engaged thousands of pedals and we were off - straight into a bright sun-rise. It would take 26 minutes for the last rider to cross the start line.

I had trained intensively for the start, doing sprint laps around London's Richmond Park. Hang the hills, if I didn't cover the first 50km without being knocked off or mown down by the peloton I had a chance of getting near the finish. As it was, the first 20 km passed off without incident with the road climbing steadily and the sun rising rapidly to ease the glare. Then, along perhaps the straightest, flattest, widest, piece of road of the whole route I was reminded just how dangerous bike-racing is.The thing with crashes is that you mainly see the aftermath, or get the story from someone else involved. It is not often you actually see one takes place. Fortunately what I am about to describe will remain a spectator experience but it sure unnerved me.

The first thing that happened was this guy losing his chain. It had some how dropped off the inner chain-ring and was flapping around uselessly. For a moment he stopped pedaling and looked down at it. At this time we were riding in a large but loosely packed group. Instead of pulling off to the side of the road the guy tried to get the chain back on by switching the front derailleur. At this point I am slightly behind and to one side of him almost amused by his predicament. Suddenly, his wheel jams and he stops dead in the road - well at least his bike tries to. The next moment he and his bike do a front flip and he smashes into the guy next him who slides directly at me. I swerve to the right and manage to avoid the collision by barely centimetres. Many people claim the actual events of an accident happen in slow motion. Not on this occasion. While I remember the details vividly, it all appeared to and probably did happen at incredibly speed - certainly at upwards of 50 kph, which wouldn't have done anyone involved much good at all.We make the first feed-stop in Guillestres, at 58.4 kilometres, in good order. While we are amongst the mountains, we haven't really done any serious climbing yet. Located on an uphill corner the feed-stop is a scene of pandemonium with the race reduced to walking pace. It is becoming worse by the minute. According to John Reed, some minutes behind, "it was grid-lock when I got there, with no place to park your bike. You had to keep it with you and fight with everyone doing the same for stuff at the tables".

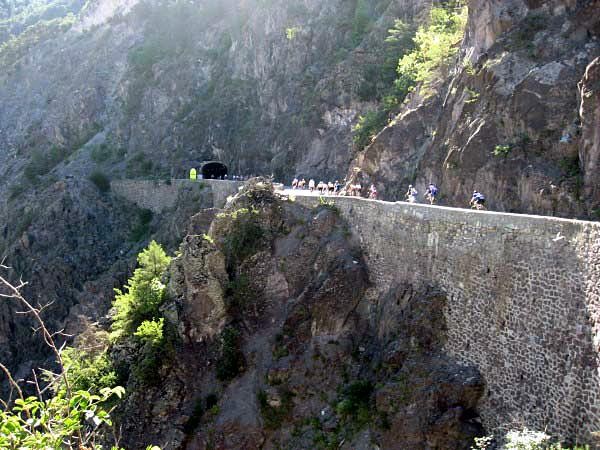

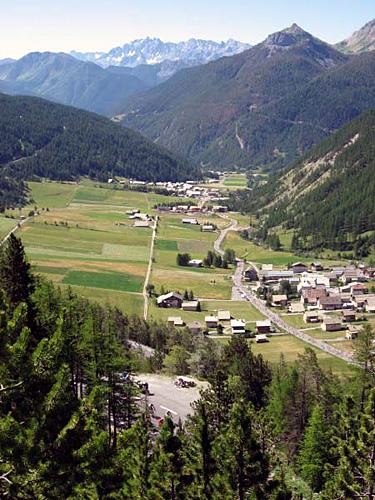

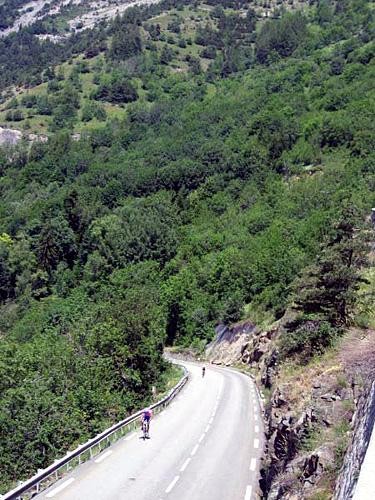

At 70 km at a sharp left turn a sign proclaimed "Col d'Izoard - 15 km au Sommet". I was actually glad to start climbing at last. From this point on the scenery went from pretty to spectacular. We were in the Combes de Queyras, an utter contrast to the first 70 km of scenery. The mountains suddenly cluster around and we are racing along gorges and through tunnels, along twisting roads etched into sheer cliff-sides. Massive cascades tumble down the rock-faces. It is almost too much to take in and keep ones eyes on the road. It is certainly dangerous to do more than glance at it. I needed to stop and take just a minute to absorb it - so what if a couple of hundred riders flash by.At Les Moulins, we have covered 76 km. The scenery opens up and we are cycling along the bottom of what would appear from an aerial photo to be a flat open valley. Except that would be very deceptive. This is one of the steepest sections of the climb, at 10 percent for nearly 4km. It is an energy sapping section with no shade, and no water, except for a village fountain, which is being mobbed.

It is ever-upwards as we leave the valley and twist and turn through trees again. But the trees don't last and we are in the Casse Dessert, a barren landscape, with towers of rock jutting out of mounds of sand. You could fake a Mars landing here without a problem. Once upon a time, this section would be a cyclist's worse nightmare - a rocky track that would either leave you caked with mud or dust depending on the weather and covered with boulders that would break a frame and more if you fell. Today it is still spectacular but the addition of a tarmaced road has somewhat sanitised the experience. We are not seeing it at the right time of day though. It is at its best when the setting sun turns the rocks a beautiful rosy hue. It is truly a beautiful place.The triumph of arriving at the summit in good form is marred by a near complete absence of water at the feed-stop. There is a sea of sorts, but it is of empty discarded water bottles. The front-runners have drunk the place dry and the feed-stop-volunteers can only shrug and tell us to get to down to the "ravitaillement" at Briançon pronto. During the mad-cap descent, now being glad of the new tarmac, I note we have just passed the half-way mark - woweeee!

Part 2, thrown at the mercy of l'Alpe d'Huez, is here.

Part 3, a colourful history of l'Etape, is here.