Giuseppe Marinoni: Steel frames and family heirlooms

Canadian frame builder hopes his bikes last 100 years

This story forms part of our North American week on Cyclingnews.

Giuseppe Marinoni, nicknamed "Pépé", is one of the most well-known bicycle frame builders in North America. After immigrating to Canada from Italy in the 1960s, he started a family business, Cycles Marinoni, in 1974, now operated with his wife Simonne and son Paolo out of Montreal.

In an interview with Cyclingnews, Marinoni talks about breaking the Hour Record while in his 80s, starting a family business and the joy and satisfaction of building durable steel bikes that last a lifetime.

Marinoni, now 84, has built upwards of 40,000 bikes over the last 50 years, and while many would say that he's perfected his craft, he says that he's still learning.

"It is difficult to know the exact number, but I estimate during busy times, we would build 2,000 bikes per year," Marinoni says.

He's created masterpieces for some of the most high-profile athletes from the US and Canada, including Connie Carpenter-Phinney, Andy Hampsten, Steve Bauer, Pierre Harvey, Gordon Singleton, along with Frenchman Yavé Cahard.

Most people who have seen video footage and photos of Carpenter-Phinney winning the road race at the 1984 Olympic Games, remember her celebrating a gold-medal performance while riding a Raleigh. Marinoni says that he built Carpenter-Phinney's bike and that it was painted with the Raleigh branding.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"I built bikes for lots of the best racers," Marinoni says. When asked if he built Carpenter-Phinney's road bike for the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, he says, "Yes, I did. At that period, bikes used by teams were not bikes that used to be built on an assembly line. It was branded Raleigh, but it was a Marinoni frame. Actually, all of the Olympic USA team Raleigh members were riding Marinoni bikes in 1984."

Hour Record

Marinoni has broken the age category Hour Record twice, first in the 75-79 category in 2012. He currently holds the 80-84 category Hour Record with 39.004km set at the Mattamy National Cycling Center in Milton, Ontario, in 2017.

He says that he doesn't actually like training, except when it's for something as distinct as the Hour Record.

"I don't train. I hate training. I train when I have specific objectives. For instance, last year, I was training to ride twice my age number on my birthday date. We were supposed to ride 166 kilometres, but it finally ended up being 170 kilometres because of a road that was closed that day, at an average speed of 30 kilometres per hour," he says.

"When training for the Hour Record, I was doing interval training, and a trainer followed me. When I go for a ride, I usually go for at least 80 kilometres, so it's worth it. I usually ride from my home since it is more efficient than having to take my car. I don't like to ride my bike. But, I know that at my age, if I stop, I will never be able to get back at it."

Marinoni captured the Hour Records while riding a bike that he built more than 40 years ago for the late Jocelyn Lovell, a nationally and internationally decorated cyclist on the track and road racing. In 1983, Lovell was hit by a truck while on a training ride and became a quadriplegic.

"For each [Hour Record], I've ridden the bike that I built for Jocelyn Lovell in 1978. The first time he used that bike, he won the Canadian Championship with his best time ever at 28 years old. Then, he won the 1978 Commonwealth Games and a silver medal at the [Track] World Championships [in Munich]. A few years later, he gave it back to me and asked me to teach him how to build bikes, which I accepted. He started building his own bikes," Marinoni says.

"I was proud of that bike, and this frame has something that I really love about it. I thought this was the best bike in the world. It is a little bit too big for me, but that's OK. If I try to break another Hour Record it will still be with this bike, for sure.

"I also would like to mention that there are only two cyclists that did break an Hour Record with a bike that they had built themselves - there is Graeme Obree and me."

Asked if he is considering breaking the 85-89 category Hour Record, Marinoni says, "Yes, although I feel a little bit uncertain right now with the whole pandemic situation going on. I spoke to the guy above us [God] to ask him if I could do that record, but he does not answer. I guess he is too busy right now with the COVID."

Welding

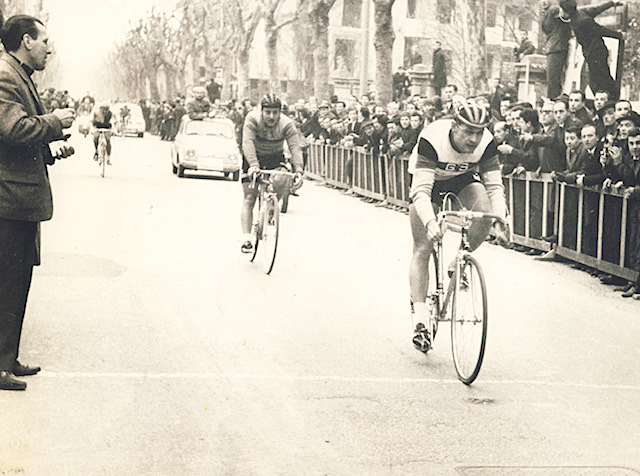

Marinoni was born in 1937 in Bergamo, Italy, and cycling has been part of his life since 17. He became the Lombardy region's champion when he was 20, but he gave up the sport and joined the army the following year.

"I raced a little bit while in the army but not much," Marinoni says." After a year and a half in the army, I came back but was not able to get back at racing because I wasn't strong and good anymore. I saw doctors, and they did not understand why. They even told me it was only in my head. Sadly, I quit racing for two years.

"After that period, I felt nostalgic and started riding again. I won a couple of races. One of them included two stages on the Circuit de Mines in France. It was many years later in Canada while training a cyclist that had mononucleosis that I understood this was what happened to me in Italy."

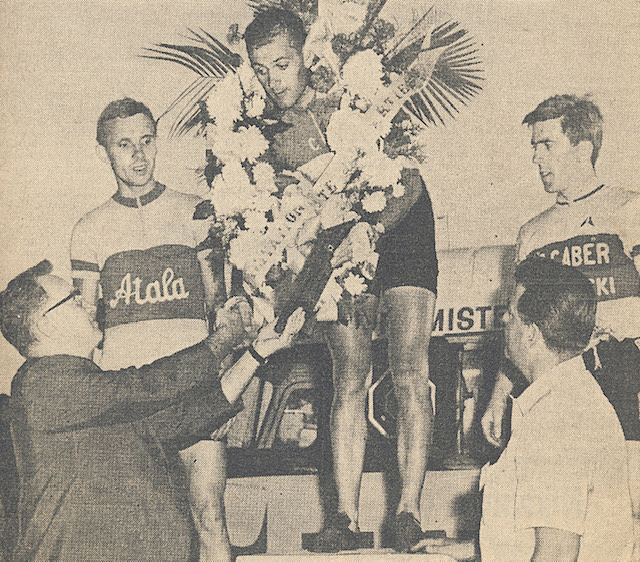

Marinoni arrived in Quebec in 1965, at the age of 27, as a bike racer and went on to win the Tour du Saguenay Lac St-Jean (1966) and twice winner of Quebec-Montreal (1966 and 1968) and twice winner of Fitchburg Longsjo Classic (1967 and 1972).

He retired from bike racing and settled in Quebec in 1972. He took on a temporary job as a tailor before meeting the now-famed steel frame welder Mario Rossin, one of five co-founders of the Rossin brand, who introduced him to the world of bicycle frame building at his workshop in Italy.

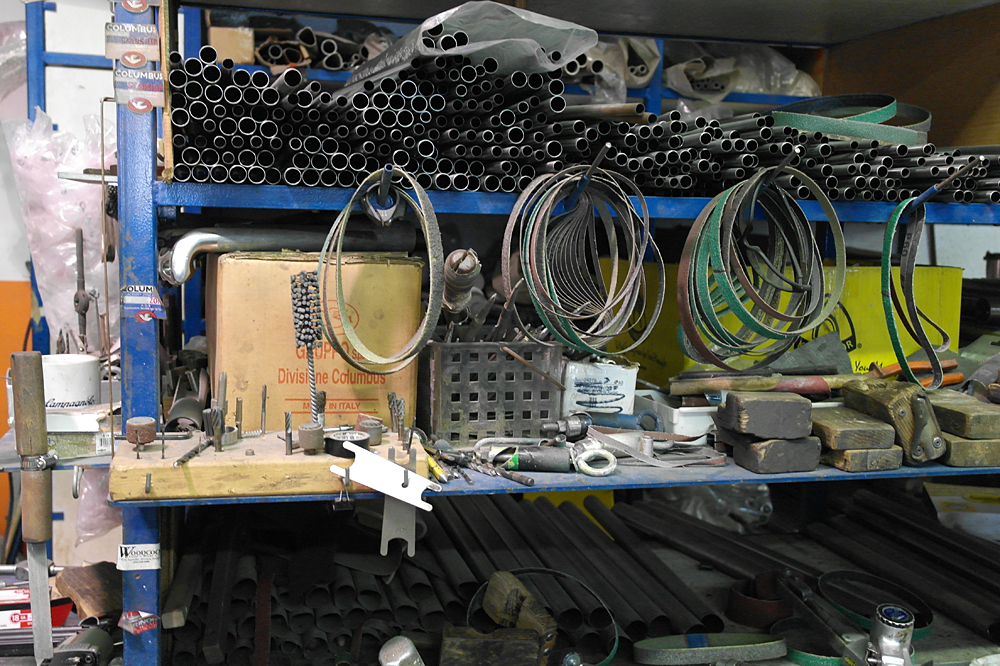

"After a couple of years living in Canada, I had a bike, and the front tube broke, but I was unable to find somebody to repair it here. I think the idea of building bikes came from that point. I thought to myself, one day, I'll build one," Marinoni says. "I had the chance to meet Mario Rossin, and I was lucky that he invited me to his workshop to learn how to build bikes. After a week at his workshop, he told me, 'OK, you've seen enough. You don't have to build bikes exactly the way that I do, but, in the end, you have to get the same results.' So, I've developed my own method."

Forty-seven years and 40,000 bikes later, Cycles Marinoni is one of the most well-known bicycle manufacturers, and some say the first, in Canada.

"I still build frames," Marinoni says. "Not as many as in the past, but I still do. Steel bike frames are not as trendy as they used to be. I still build around 20 steel bike frames per year. The technique is always the same. Although, I might even be improving on my technique to this day.

"This might be the last year that I build bikes, who knows … I've also been lucky enough to have my wife Simonne involved in the business since day one. I wouldn't have succeeded without her by my side. My son Paolo has also been involved for more than 30 years and is now running the business."

Heirlooms and making people happy

Marinoni was the subject of a full-length feature by Montreal-based filmmaker Tony Girardin titled Marinoni: Fire in the Frame (2014) that documents his everyday life as a frame builder in his workshop in Montreal. It's something of a character study, too, that picks up on Marinoni's eccentric personality and his lifelong passion for cycling.

"I've watched [the film], and it's pretty accurate. It's the true story. I'm proud of the portrait of myself that is portrayed in it. I'm happy that once I'm gone, this documentary will still exist and tell my story," he says.

Asked if he agreed with the way that he is often described in the Canadian media - a legend, local hero, eccentric, and even solitary or reclusive, and with a sense of humour - Marinoni thinks about his response.

"Legend, local hero? I don't know. Eccentric? What does this word mean again? Stubborn? Maybe. Solitary? Certainly not!" he says.

"Yes, I have a sense of humour, for sure. I would say that I'm very passionate. When I work, I give my 100 per cent, and if somebody is not happy about my work, I just don't want to lose time with that person."

He may consider retiring from frame building this year; however, he also says he can't picture himself not building bikes.

"I wish I die while building a bike, not while riding a bike. You should see someone's face when you give them a bike that you've built yourself, just for them specifically. Seeing that person happy makes me the happiest person in the world."

Marinoni doesn't consider himself a cycling legend, but he hopes that people remember him for his hand-crafted steel bicycle frames and that they will become long-lasting family heirlooms.

"As a cyclist, I hope people remember me as a racer with good fair play, and that kept his promises," Marinoni says. "I wish people remember the steel bikes that I've built over my career. They are so strong that you'll see some on the road 100 years from now. The proof is that you now see some that are 30 or 40 years old on the road. I wish people remember me as a great frame builder."

Kirsten Frattini is the Deputy Editor of Cyclingnews, overseeing the global racing content plan.

Kirsten has a background in Kinesiology and Health Science. She has been involved in cycling from the community and grassroots level to professional cycling's biggest races, reporting on the WorldTour, Spring Classics, Tours de France, World Championships and Olympic Games.

She began her sports journalism career with Cyclingnews as a North American Correspondent in 2006. In 2018, Kirsten became Women's Editor – overseeing the content strategy, race coverage and growth of women's professional cycling – before becoming Deputy Editor in 2023.