Giro d'Italia history: Indurain on doing the Giro-Tour double

Spaniard one of just seven men to complete the feat

In the run-up to what would have been the 2020 Giro d'Italia, we look at the historical feat of the Giro-Tour double with the most recent surviving champion to accomplish it.

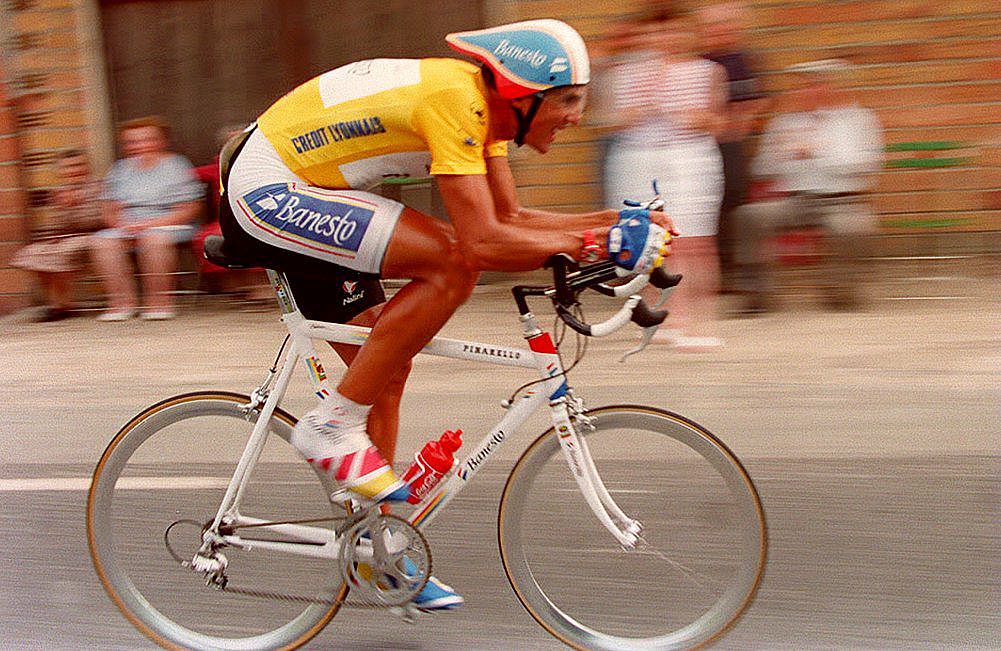

While this year's compressed autumn racing calendar would make such a feat nigh on impossible – should said calendar even come into being – Miguel Indurain's advice is timeless. The story of his two double victories, in 1992 and 1993, rank up there with other legends of the sport to achieve the double – Fausto Coppi (twice), Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx (twice), Bernard Hinault (twice), and Marco Pantani.

Here, Indurain looks back at his second, 1993 double, while also giving advice on what it would take to do the double in the modern day.

This article was previously published in Procycling magazine in 2015.

Procycling magazine: the best writing and photography from inside the world's toughest sport. Pick up your copy now in all good newsagents and supermarkets, or get a Procycling subscription.

Indurain's impact on the Giro d'Italia was – and remains – enormous. He was the first Spaniard to win the Giro, and his back-to-back victories there, in 1992 and 1993, make Indurain the only rider ever to net a 'double double' of Giro-Tour victories in two straight years.

In 1992, the Giro's final time trial – a 66km affair on the last day – was a huge concession by the organisers in Indurain's favour. But long before that, Indurain had already moved into pink and was looking good to win.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Far better against the clock than his key rivals – Claudio Chiappucci and 1991 overall winner Franco Chioccioli, not to mention outsiders Andy Hampsten and Laurent Fignon – Indurain started to forge his second Grand Tour victory by winning stage 4's 38km time trial. He then defended the leader's jersey for the rest of the race.

Eighteen days later – game over. OK, it wasn't actually quite that simple, but almost. Key mountain stages, such as the summit finish on the Terminillo on stage 10 or the two days in the Dolomites at the end of the second week, couldn't crack Indurain. The trio of set-piece mountain stages in the race's final week – to Pian del Re, Pila and Verbania – equally failed to dent Indurain's advantage.

"They are attacking me less and less," he said in one of his typically brief press conferences after stage 18.

Come the final monster 66km time trial into Milan, Indurain was already clearly en route to victory. Overall, Indurain's victory by five minutes and 12 seconds on rival Chiappucci – who he caught, despite the Italian starting three minutes ahead, during the final time trial – hugely increased expectations in Spain concerning Indurain's chances of winning the Tour, too.

He had no problems doing that either, taking his second straight Tour de France in even more confident style than the first.

His 1993 Giro victory was far less straightforward. It began with Indurain getting stuck in the Alps before the race had even started because of a hurricane, and it ended in controversy – albeit not for Indurain specifically, but for his team.

There were accusations that Festina had shown a suspiciously high degree of collaboration with Banesto during the race. The charges led to a big reshuffle among the Festina team's management, with Bruno Roussel, later to face charges of organising doping in the squad in the 1998 Tour, taking over as team manager.

That was more still to come. Indurain's main concern immediately prior to the race was just getting there. Following the one-day Giro dell’Appennino, he flew by helicopter to reconnoitre the Giro's potentially decisive third-week 55km Sestriere uphill time trial. Sestriere was, in 1992, the scene of a devastating long-distance attack on Indurain by Chiappucci at the Tour.

Now it was causing Indurain problems in a different way with a major Alpine storm making a flight to the Giro start at Elba impossible.

Eventually the Spanish rider made it to Elba using a rather unglamourous means of transport: he hitched a ride in the Banesto team lorry, travelling over from Spain with two mechanics, then reached Elba by ferry just one day before the race start.

"I almost thought we wouldn't make it," he commented.

More headaches were to come. The considerable reduction in the Giro's time trial kilometres meant that Indurain only moved into the pink briefly after taking the very hilly mid-race chrono – 28km rather than 60km – in the Adriatic town of Senigallia. He then ceded the top spot to Bruno Leali. Rather like his 1991 Tour de France, where he moved into yellow in a Pyrenean mountain stage, not in a time trial, Indurain's tactics were to grind his rivals out of contention on the climbs, then kick them out of touch for good in the final time trial.

The Spaniard duly took over the lead once more on stage 14 to Corvara – an extremely tough 245-kilometre mountain stage with five classified climbs. He shredded the field on the Marmolada – squeezing his rivals down to a bare three or four – and when Chiappucci attacked, he followed him to the line. Chiappucci took the stage but Indurain got the top prize.

Even though Indurain increased his advantage at the Sestriere time trial, where he put the rest of the field to the sword with an impressive stage win, there were still some fireworks to come. Lithuanian Piotr Ugrumov, for one, gave Indurain a much closer run for his money in the Oropa climb on stage 20. One attack after another by Ugrumov, coupled with some digs by Stephen Roche and Chiappucci, finally saw Indurain sit up and let Ugrumov go clear.

Banesto director José Miguel Echavarri seemed far more nervous than the ever-implacable Indurain, overtaking the rest of the race convoy vehicles in dramatically illegal style to shout at his protégé, "Take it easy, Miguel – the most you can lose is 30 seconds."

As it was Indurain lost 36, but the final overall difference between him and Ugrumov of 58 seconds made it clear how close the final gap had been. Echavarri was fined a hefty 24,500 pesetas for his driving (£140, or about £260 today) but said he was not bothered, given how close Indurain was to winning and the imminent celebrations.

As Echavarri put it, "It's not important. Soon I'm going to spend more on champagne." He was right, and had even more reason to celebrate when Indurain claimed his third straight Tour that July.

Experience, according to Indurain, rather than freshness of form, is the key to success in a double Grand Tour challenge.

"The older you get, your form gets more consistent and lasts for longer. So that's definitely a plus when it comes to Grand Tours.

"The Giro-Tour double is definitely doable, but you've got to have the right mentality and you have to know how to spend your energy, and when. You can't just go rushing into the start of the season, for example; you have to take things a bit more slowly, and get closer to your top level when you get closer to the start of the Giro itself."

Indurain himself knew that "from the start of each year that I'd be going for the double, but the Giro wasn't ever my main objective. It was all about the Tour. If I did a good Giro, well, that was a bonus."

In any case, the Giro at that time, Indurain says, was very different in feeling to how it is today.

"It was much more homely, much more the Italians' own Grand Tour where foreign riders didn't carry much weight or have much effect on the racing. These days, the type of participation is another story – far more international and more similar to the Tour de France. I don't know if that’s because of the ProTour [sic] – maybe – but it's certainly changed."

Back in his time, it reached a point, Indurain says, when the Italian influence on the Giro d'Italia was so great that "in Banesto we had to adapt our racing style to how they raced – not the other way round".

As for the long-term physical effects of a Giro-Tour: "They don't just last a few months; they go right the way through to the next season. I was still tired in 1993 when I did the Giro, and the Giro was much more difficult for that reason, from having raced so hard in 1992 and doing a double back then."

Indurain's advice for any of today's riders regarding how they should tackle the period between the Giro and Tour is that… there is no straightforward advice.

"What's good for one rider is rubbish for another; what one rider likes isn't any good for the next; and so on and so forth. You've got to do that case by case. Another factor is whether the hardest part of the Tour is earlier or later in the race; that affects how you tackle each.

"So there are a lot of different ingredients that affect what you do. General advice doesn't work. All I can say is: doing a Giro-Tour double is very complicated."

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.