Giro d'Italia 2019: The ambush stages

Shining a light on where the 2019 Corsa Rosa could be lost

The Giro d'Italia has always tended to be won and lost in the final week, and, on first glance, this year's route appears to take that concept to new extremes. As ever, the toughest days are shoehorned into the latter part of race, but, this time around, the first mountain leg doesn't arrive until stage 13.

Indeed, the only uphill finishes on offer in the first half of the race come in time trials – namely the short, sharp hill climb in Bologna on stage 1, and the steadier grind from Rimini to San Marino on stage 9. Logic says that those two time trials will define the general classification ahead of the race's entry into the Alps at the end of week two, but, as recent history demonstrates, a Giro can sometimes take on a life of its own.

The 2015 route, for instance, was strikingly similar to this year's, with the main obstacles backloaded to the final week in a bid to entice the luminaries of Grand Tour racing to take on both the Giro and Tour. In the event, Alberto Contador was the only man to take on the challenge, but while the route seemed amenable to his double attempt, the opening fortnight proved rather more wearying than anticipated, thanks largely to the constant aggression of the Astana team.

A year ago, meanwhile, Esteban Chaves' challenge fell apart in the most unexpected of circumstances on the road to Gualdo Tadino on stage 10, while the stage to Sappada provoked bigger time gaps than the preceding afternoon's rather-more-hyped haul up the Zoncolan.

In short, anything can happen on any given day at the Giro. The topography of the country and the nature of the race make it so. The key stages of the Giro – the time trials and the mountain days – are obvious, but all along the peninsula, there is ample opportunity for ambushes.

Stage 2, May 12: Bologna – Fucecchio, 205km

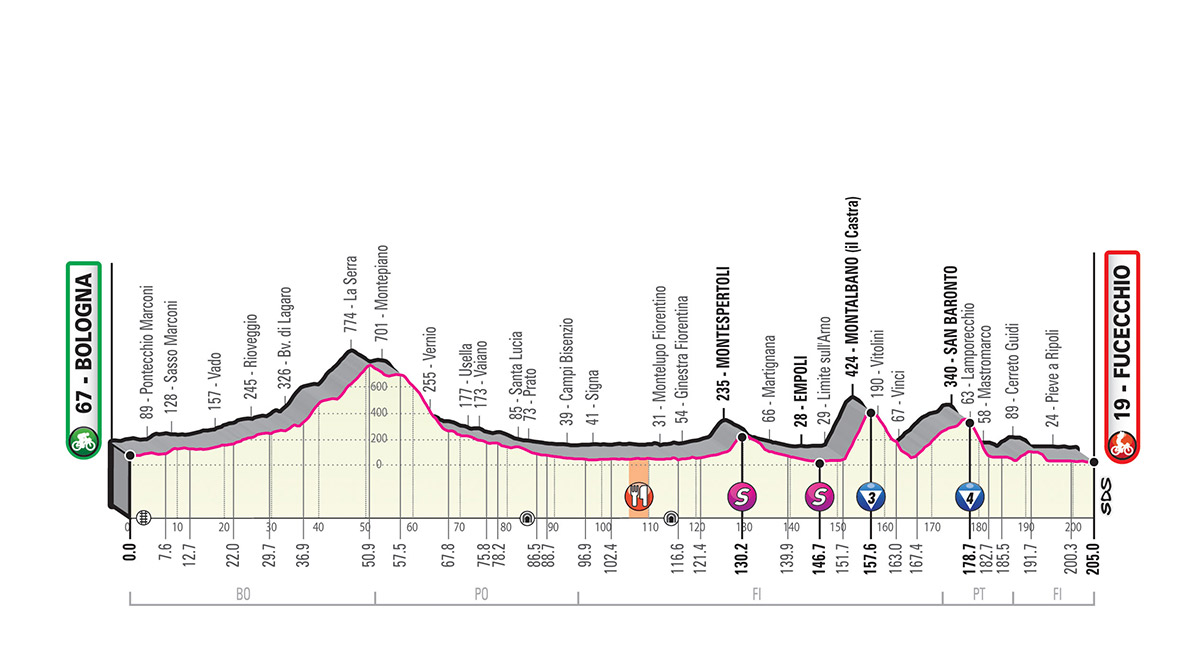

It's difficult to envisage the opening road stage of the Giro ending in anything other than a bunch sprint, not least because of the rapid approach to the finish in Fucecchio and the organisation of teams such as Elia Viviani's Deceuninck-QuickStep. That's not to say, however, that stage 2 is bereft of potential pitfalls for the general classification contenders.

Beyond the usual nervous tension – and associated risk of crashes – that characterises such occasions, the Giro's foray into Tuscany also takes in some rolling terrain that will demand considerable vigilance. While the early and gradual ascent towards La Serra should allow the morning break to sally clear, the climbs in the latter part of the stage will be rather more stressful.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The short and sharp category 3 ascent of Il Castra (5.8km at 6.8 per cent) is followed in rapid succession by a quick drop to Vinci and the punchy climb to San Baronto – home of the absent Neri Sottoli team. The topography is just tough enough to stretch and maybe even split the peloton, although the 25km run-in to the finish offers a chance to recoup lost ground.

In the ordinary run of events, no GC contender would expect to concede anything here, but in a Giro as backloaded as this one, there will inevitably be some riders who set out slightly undercooked with the aim of riding their way into form as the race progresses. This early run through the Tuscan hills is a test of that strategy's wisdom.

Stage 6, May 16: Cassino – San Giovanni Rotondo, 233km

Since the tumultuous 2011 Giro, where, among other hardships, the gruppo went from the top of Mount Etna to the Austrian Alps in the space of five days, organisers RCS have made a conscious decision to cut back on the frequency and length of post-stage transfers. In this regard, the opening sequence of the 2019 Giro seems exemplary, with finish towns regularly doubling as the next day's start.

The trade-off, however, is that the peloton must take on a succession of seemingly interminable stages by way of compensation. One way or another, the Corsa Rosa still has to make its way down the peninsula and back north again before its mountainous denouement, meaning that there are five stages of 200km or more in the opening week alone.

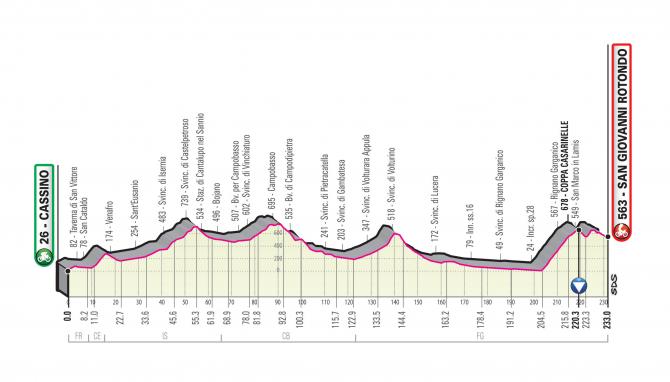

Those long efforts may start to tell by stage 6 from Cassino to San Giovanni Rotondo, which itself comes in at 233km and brings the race to its southernmost point. After four successive flat and fast days, the opening part of this stage seems woven from the same cloth. The first 100 miles or so take the gruppo from Lazio and across Molise through relatively gentle terrain and along wide roads, but the lie of the land alters considerably after the race crosses into Puglia.

The roads become narrower in the final 50km, while the surface is notably rough in places. The finale, meanwhile, is a hilly and sinuous affair. The category 2 ascent to Coppa Casarinelle (15km at an average of 4.4 per cent) is not especially difficult, but the summit comes just 18km from the finish.

More pertinently, there is not much of a descent afterwards. Instead, the punchy rise to the sprint at San Marco in Lamis and another short, stiff incline shortly afterwards offer an enticing springboard for attackers on the run-in. GC contenders cannot afford to switch off mentally once they have crested the summit of the day's lone classified climb.

Stage 7, May 17: Vasto – L'Aquila, 185km

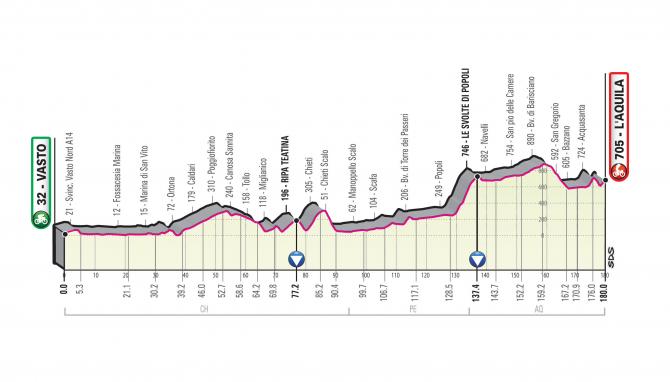

The Giro begins the trek back towards the mountains of the north with a stage for puncheurs in the hills of Abruzzo. The day begins with a decidedly gentle amble along the Adriatic coast from Vasto, but the difficulty increases once the race swings inland at Ortona after 40km, and the road ripples through the hills that pockmark the hinterland of Chieti – a locale familiar from Tirrreno-Adriatico.

The key perils in this stage are to be found in the breathless final 60 kilometres, beginning with the category 2 climb to Svolte di Popoli, which is the only classified ascent on the day's agenda. The road drags upwards for 8.9km at an average of 5.6 per cent and, in an echo of the previous afternoon, the day's main obstacle is followed by a deceptively tough epilogue, namely the billowing plateau that leads towards the finish in L'Aquila.

The road rises and dips as it winds around L'Aquila in the final 10 kilometres, starting with the short but stiff ascent of Via della Polveriera, where the gradient pitches up to 9 per cent. A technical descent follows, concluding with a sharp right-hand turn with 2km to go. The last 1,500 metres are a leg-stinging climb towards the citadel, with an average gradient of 7 per cent and a maximum of 11 per cent.

It is the kind of punchy finish that was so favoured by local favourite Danilo Di Luca, and indeed the self-styled 'Killer' – later banned for life after testing positive in 2013 – won when the Giro visited L'Aquila in 2005. The race returns this year to mark the 10th anniversary of the earthquake that devastated the city.

Although finisseurs such as Diego Ulissi will surely be to the fore, a strikingly similar finale in Osimo a year ago was ultimately dominated by two GC men, as Tom Dumoulin stalked maglia rosa Simon Yates all the way to the line. The seconds won and lost in L'Aquila won't be decisive, but they might be telling in their own way.

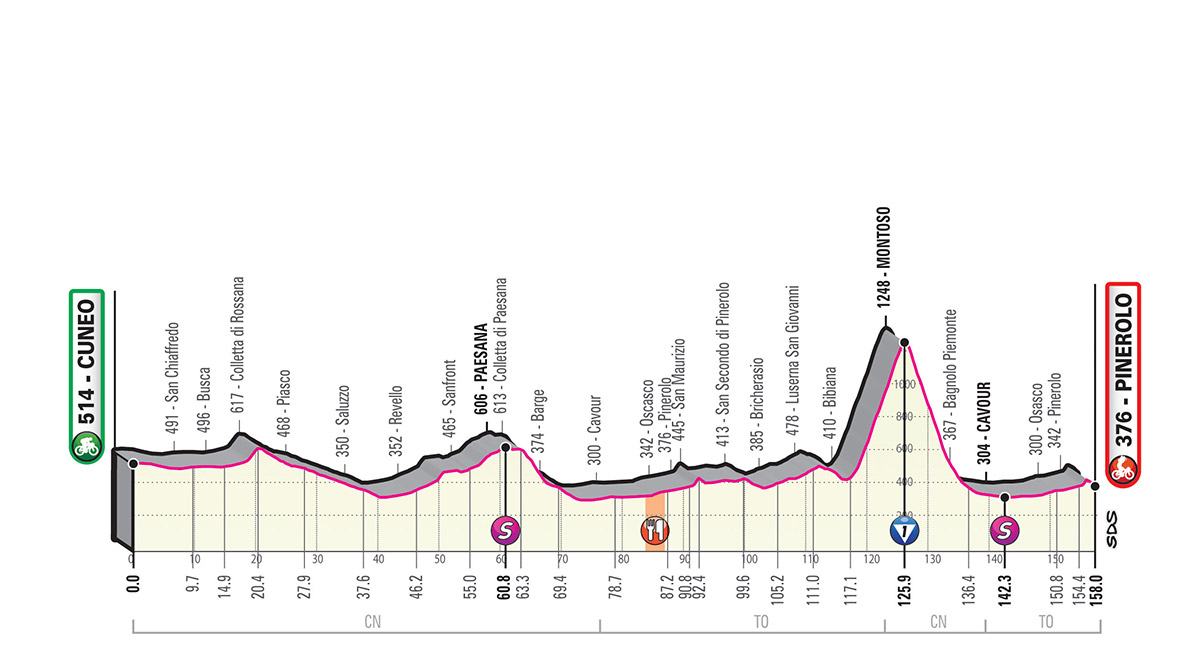

Stage 12, May 23: Cuneo – Pinerolo, 146km

The words 'Cuneo' and 'Pinerolo' instantly conjure up thoughts of 1949, and all that. Stage 17 of that year's Giro was the scene of Fausto Coppi's most storied impresa: the 192km raid over the Maddalena, Vars, Izoard, Montgenevre and Sestriere that saw him seize the pink jersey and seal overall victory. Just as pertinently, the day marked an historical passing of the torch from Gino Bartali to Coppi. The first draft of history in the following day's Corriere della Sera came to be enshrined into the lore of the race, as novelist Dino Buzzati compared the sight of Coppi distancing Bartali on the Izoard to Achilles slaying Hector.

It seems unlikely, however, that the sala stampa will find cause to dust off Homeric metaphors in their reports of this year's stage from Cuneo to Pinerolo. As in 2009, RCS will pay homage to Il Campionissimo with an evocative combination of start and finish towns but, as in 2009, the road taken will be rather underwhelming by comparison with the trail followed by Coppi, Bartali et al 70 years ago.

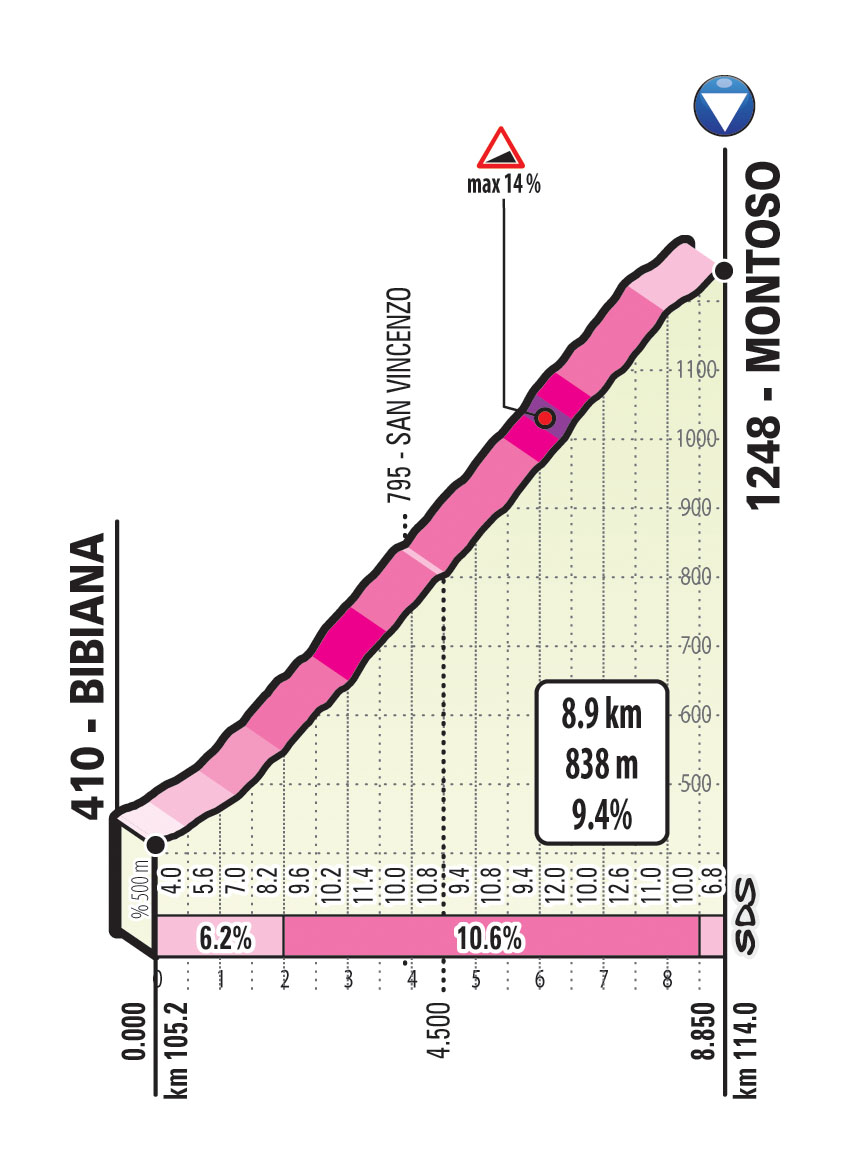

Even so, it would be remiss to describe the stage as a mere transitional day ahead of the Giro's entry into the Alps proper 24 hours later. There may be just one classified climb on the route – the category 1 Montoso – but the brevity of the stage and the constant undulations mean that this stage has the potential to ignite if one or more of the maglia rosa contenders are so inclined, as Alberto Contador was on a similar leg to Verbania in 2015.

The early part of the stage takes the race through the gentle hills of the Langhe, but the road grows rather more arduous once the gruppo passes through Pinerolo for the first time after 90km. The climb to Montoso is 8.8km in length with an average gradient of 9.5 per cent and a maximum slope of 14 per cent. The summit comes 32km from the finish, but there is an interesting sting in the tail in the form of the short but brutally steep climb to San Maurizio. The 550m-long muro pitches up to 20 per cent and comes with just over 2km to go.

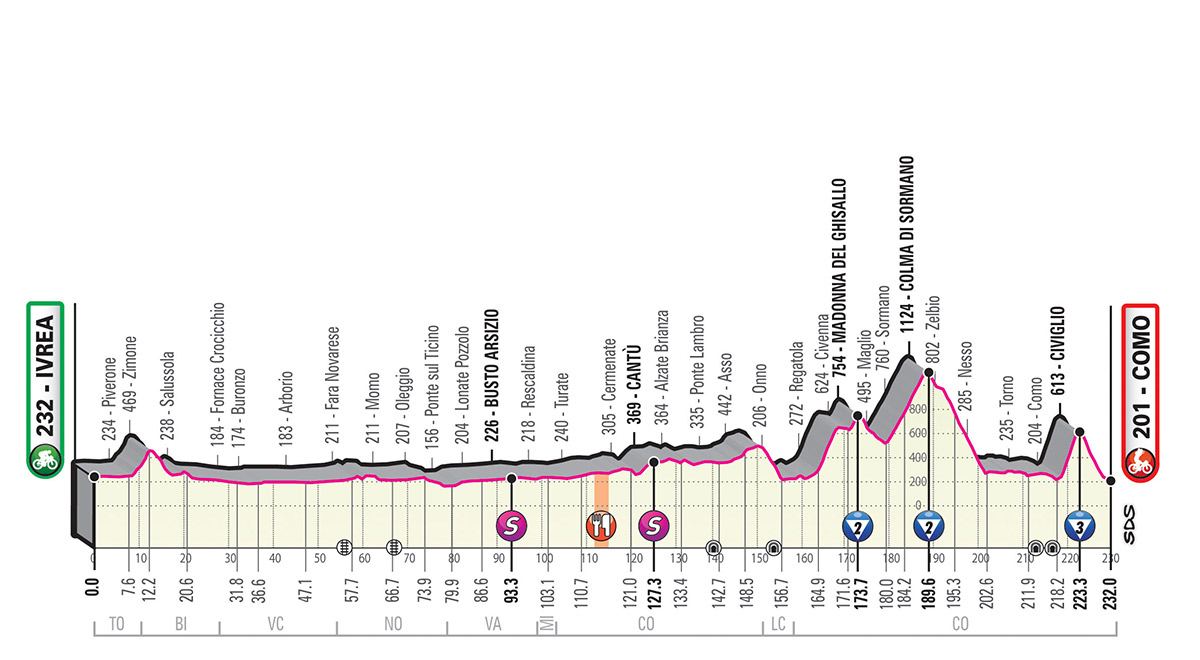

Stage 15, May 26: Ivrea – Como, 232km

The Giro organisers have given this stage a four-star rating, commensurate with a full-blown mountain leg, and the roads that hug the shores of Lake Como are familiar from Il Lombardia, so nobody can say they weren't warned about the difficulty of this (only slightly) scaled down version of 'The Race of the Falling Leaves'. And yet, given that it falls between the Giro's first bona fide mountain stages and the tappone over the Gavia and Mortirolo, one could be forgiven for overlooking the bookend to the race's second week. Riders who have not recovered from the Colle San Carlo and the Nivolet will be aware that they could pay a hefty price here.

The opening 100 miles are largely flat, but the stage takes on a rather more monumental guise once it hits the eastern branch of Lake Como at Onno. First up is the Madonna del Ghisallo (8.6km at 5.6 per cent), followed in rapid succession by the Colma di Sormano (9.6km at 6.6 per cent). Although the route avoids the steep Muro di Sormano at the top, the terrain is tough enough for a team like Astana to force a significant selection, especially two weeks into the Giro.

The final ascent to Civiglio is – like in October – an ideal platform for a race-winning attack. The summit comes just 9km from the finish, and men like Simon Yates (Mitchelton-Scott) will surely view the climb (4.6km at an average of 9.6 per cent) as an ideal opportunity to snaffle some more valuable time ahead of the Giro's second rest day. The time trials and set-piece mountain stages might provoke the biggest time gaps, but at the Giro, perhaps more than any other Grand Tour, every day counts.

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.