Giro d'Italia 2018: Five key stages

Zoncolan, the Rovereto time trial and the Alpine denouement

On his lone appearance in the race almost 30 years ago, Paul Kimmage was moved to bemoan that the Giro d'Italia was far harder than previously advertised. 'Where was the Giro of legend, where riders laughed and joked for five hours and raced for two?' he wrote after an especially relentless slog across heavy southern roads between Potenza and Campobasso during the opening week of the 1989 Giro.

Giro d'Italia 2018: Zoncolan and final Rome TT likely as route details emerge

Chris Froome confirms Giro d'Italia participation

2018 Giro d'Italia route revealed

A history of Giro-Tour double failures

2018 Giro d'Italia route unveiled in Milan - Gallery

'A start fee for Froome? I flatly deny that,' says Giro d'Italia director

Nibali warns Froome about the unpredictability of the Giro d'Italia

Giro d'Italia removes reference to 'West Jerusalem' following Israeli protest

If anything, the Giro has only grown harder in the decades since. True, at the turn of the century, Mario Cipollini still had the sway to warn a young Thomas Voeckler off the idea of attacking early on a flat stage, and in 2004, the gruppo seemed to call a truce at various points as Alessandro Petacchi quietly annexed nine sprint wins, but such instances are increasingly rare in the modern Giro, where every day counts.

The 2015 edition of the race was a case in point. Alberto Contador lined up targeting a Giro-Tour double and, with that goal in mind, RCS Sport seemed to have designed a particularly amenable route. With the most difficult stages shoehorned into the final week, Contador had – in theory – a chance to ride his way into form as the race left San Remo.

Astana, however, had other ideas, and from the Riviera down to Campania and all the way back north, they waged guerrilla warfare against Contador, lining out the peloton at every opportunity, and turning the supposed procession into a trial by ordeal. Although Contador reached Milan in the pink jersey, it came at a cost. Exhausted, he was a shadow of himself at the Tour de France – which had, of course, been part of Astana's game plan. As one Astana staff member explained, Fabio Aru's job wasn't so much to win that Giro as to make sure Contador was too tired to challenge Vincenzo Nibali at the Tour that followed.

In 2018, for Alberto Contador, read Chris Froome. For Astana, read Movistar (and others). The four-time Tour winner may be about to receive a monstrous payday to compete at the Giro, but he won't get too many free rides between Jerusalem and Rome next May.

In that context, picking out five key stages at the 2018 Giro feels almost redundant, but – at a remove of six months – some stages leap off the map all the same.

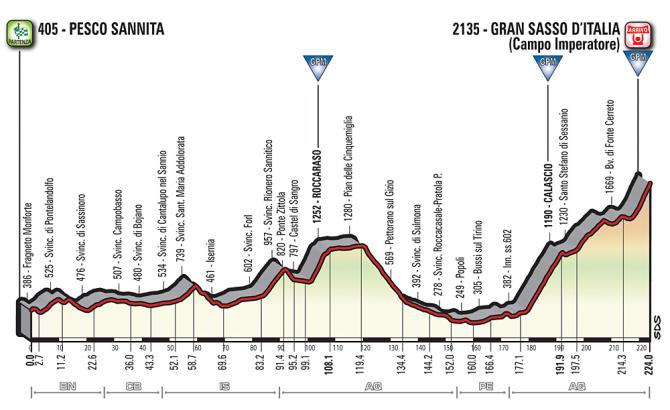

Stage 9, May 13: Pesco Sannita - Gran Sasso d'Italia (Campo Imperatore), 224 kilometres

The summit finish at Mount Etna by way of the steep Valentino approach arguably makes stage 6 the toughest proposition of the opening week, and RCS has duly assigned the stage a four-star difficulty rating, but such early mountain stages in Grand Tours often tend to be tentative affairs – as was the case on Mount Etna last May.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

By stage 9 to Gran Sasso d'Italia, some general classification contenders might be surer of their form and others might already be flagging after eight race days and the lengthy transfer from the Grande Partenza in Israel. This lengthy stage on the eve of the second rest day is also the Giro's last obvious, set-piece stage ahead of the demanding third weekend in Friuli, and it would be a surprise if the principal contenders didn't at least test the waters here.

At 224 kilometres, the stage is one of the longest in the Giro, and although there are just three categorised climbs en route, there is scarcely a metre of flat once the flag drops in the province of Benevento. The ascent of Roccaraso above Castel di Sangro is familiar from the Giro's finish at the summit in 2016, but the stage's true difficulty lies in the final 50 kilometres, as riders tackle something a two-part ascent to the line.

First up is the 14.8km haul to Calascio, which pitches up to 10% near the summit. Rather than descend the other side, however, the Giro will then follow a short plateau before facing directly into the final ascent to the finish Gran Sasso d'Italia. The climb isn't especially steep, but it yawns inexorably upwards for 26 kilometres and seems especially well suited to Sky's usual template of (very brisk) tempo riding on the front. Marco Pantani was the last winner at Gran Sasso d'Italia in 1999, when he burnt Ivan Gotti and José Maria Jimenez off his wheel on snow-banked roads.

Stage 14, May 19. San Vito Al Tagliamento - Monte Zoncolan, 181 kilometres

Like the Angliru, summit finishes at Monte Zoncolan always catch the eye when the route is announced. Yet while the stage is sure to be one of the most talked about and most visually spectacular of the entire Giro, the jury is out as to whether it will be decisive. Since the Giro first visited the Zoncolan in 2003 (on that occasion by a gentler route than the classic ascent from Ovaro), the stage has always been a notable one, but only occasionally a truly pivotal one.

The Zoncolan was something of a keynote victory for Ivan Basso in 2010, setting the tone for what he would do in the final week of that Giro, but on other occasions, the pink jersey contenders have taken a more cautious approach on the so-called Kaiser. This is in part because the sheer steepness of the gradient arguably places a natural limit on the time gaps that can be provoked. On sustained slopes in excess of 20%, the strongmen and dropped riders alike are forced to grind their way up the mountain, and gaps develop in inches rather than simply yawning open. It all makes for most compelling television, but – more often than not – the time gaps on the results sheet at day's end can be modest.

No matter, stage 14 from San Vito al Tagliamento is a brute. The climbs of Monte di Ragogna and Avaglio should not cause undue problems, but the terrain becomes more rugged thereafter, with the short but viciously steep Passo Duran – which includes an 18% wall at the base – and Sella Valcalda sure to whittle down the pink jersey group long before it enters the football stadium atmosphere of the Zoncolan itself (10.1km at 11.9%).

The following day's insidious leg to Sappada – 31 years on from Stephen Roche, Roberto Visentini and all that – might ultimately prove more decisive, but anything can happen on the Zoncolan, as Francesco Manuel Bongiorno discovered when he was impeded by an overly-enthusiastic fan while part of the winning move in 2014. Decisive or not, the Zoncolan is always box office.

Stage 16, May 22. Trento – Rovereto (ITT), 34.5 kilometres

The 2017 Tour de France showed that it doesn't necessarily take a lot of time trialling miles for the discipline to have a very big impact on the general classification, and RCS Sport appear to have taken the lesson board. On last year's Giro, after all, Tom Dumoulin effectively won the race in the space of one time trial at Montefalco, and were it not for his abrupt toilet stop on the Stelvio, the race could have been divested of all suspense long before the finish in Milan.

This time around, Dumoulin and the rest will have to subsist on a far more meagre time trialling diet. The twisting test in Jerusalem on stage 1 is a mere 9.7 kilometres in length, and the only other time trial on the route comes at the beginning of the final week in Trentino.

The rolling terrain of the 2017 Montefalco time trial made it the kind of stage where a bad day could quickly escalate into a disastrous one, as Nairo Quintana found to his cost. The 34.5km stage from Trento to Rovereto is rather less technical and more straightforward, but there is still scope for a Dumoulin or a Froome to leave a rider like Fabio Aru with an insurmountable deficit to make up in the final days. In any case, the imminent time trial will influence how many riders approach the second week, and its outcome will dictate how they much race the final days in the Alps. The lack of a final time trial in Rome, meanwhile, will please Froome far more than Dumoulin, assuming the Dutchman comes to defend his crown.

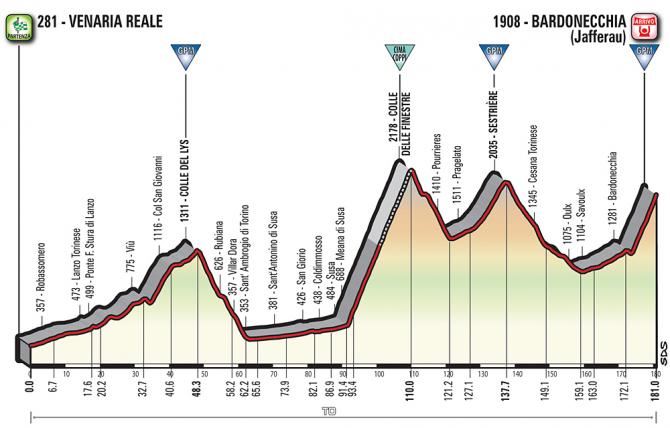

Stage 19, May 25. Venaria Reale – Bardonecchia, 181 kilometres

When the Giro last finished in Rome in 2009, there were complaints that the climbs in the final days of the race – including a finish on Mount Vesuvius – were rather lacking in comparison with the corsa rosa's usual high mountain denouement. Whether by accident or design – there were lingering doubts over whether Rome or Milan would host the final leg of the Giro – the issue has been avoided this time around. The gruppo will face a most demanding trio of stages in the high Alps in the dying days of the race before flying from Turin to Rome for the final passarella around the Coliseum.

Stage 18 to Pratonevoso provides a relatively gentle opening, with just the 13km haul to the finish to trouble the GC men, but stage 19 to Bardonecchia is arguably the tappone of the Giro. After being flagged away from Venaria Reale, just outside Turin, the softening-up process begins as the race ascends the long Colle del Lys, before the mighty Colle delle Finestre rears into view. At an altitude of 2178 metres, the Finestre is the Cima Coppi, the highest of the Giro. It grinds inexorably upwards for 18.5km with the gradient flitting between 9 and 10% all the way, with asphalt giving way to dirt road for the eight kilometres preceding the summit. The Finestre provided ample spectacle on the final weekend in 2005 and 2015, and though the summit is still some 70 kilometres from the finish here, it will surely provide one of the most stirring passages of the Giro.

After a short descent, the race takes on the gentler, 16km climb to Sestrie, before the short but steep haul to the finish on the Jafferau, situated above the ski resort of Bardonecchia. Just 7.25km long, the climb still packs a punch. The gradient hits 14% at the base, and barely relents thereafter. On its last appearance in 2013, Vincenzo Nibali and Mauro Santambrogio – who later tested positive – forged clear in the final on a snow-shortened stage.

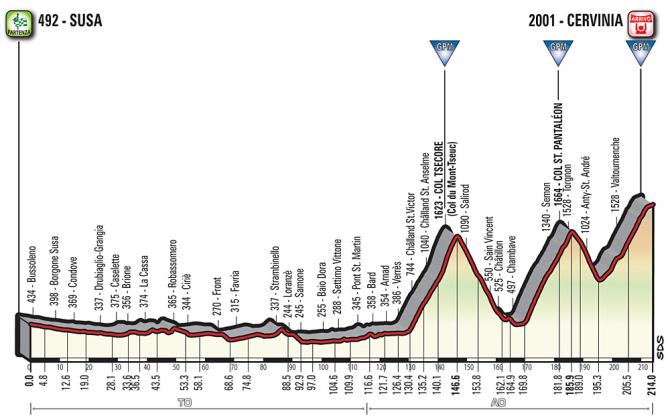

Stage 20, May 26. Susa – Cervinia, 214 kilometres

All or nothing. With only the final procession in Rome to come, the 2018 Giro effectively ends atop Cervinia. Mauro Vegni's dream scenario would surely be to have one of the marquee names – Aru or Froome himself – forced to launch a desperate offensive to snatch the maglia rosa, just as Vincenzo Nibali did on the road to Sant'Ana di Vinadio in 2016. The stage in Valle d'Aosta takes in terrain that has proven decisive at the Giro in the past – Ivan Gotti moved into the overall lead in 1997 after attacking on the Col St. Pantaleon ahead of the finish at Cervinia.

At 214 kilometres in length, the stage should began rather sedately for the remaining podium contenders, before igniting in the final 80 kilometres, which feature three mountain passes. First up is the Col Tsecore, which drags on for 16 kilometres and gets steeper towards the summit, with pitches of 15%. After a fast, sweeping drop to Chambave comes the St. Pantaléon, which – also 16km long with its toughest stretches near the top – is strikingly similar to the Tsecore.

The final climb of the Giro towards Cervinia, meanwhile, is a long but relatively steady affair. 19km in length with a maximum gradient of 12%, the ascent is far from the toughest on the Giro, but after three weeks of racing – not to mention three demanding days in the Alps – it is just hard enough to punish any weaknesses. A fitting end, perhaps, to race of attrition.

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.