Giro d'Italia 1998: Double vision

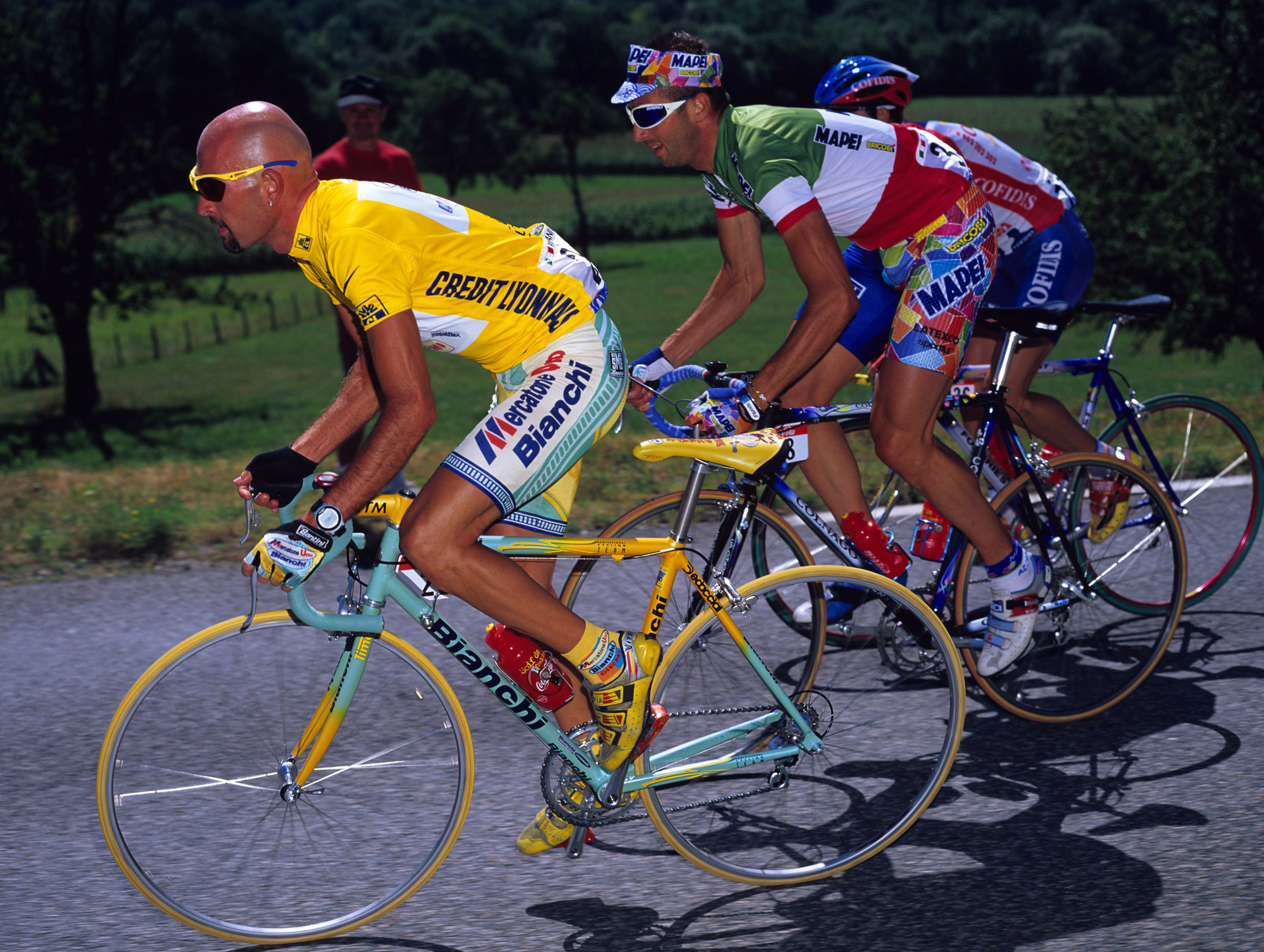

Procycling magazine rewinds to 1998, the year of Marco Pantani's Giro-Tour double

In 1998 Marco Pantani took historic wins in both the Giro d’Italia and Tour de France. It was also the year of the Festina Scandal, at the second race, which changed the public view of cycling. Procycling looks back at a summer of momentous change.

This article was taken from Procycling magazine issue 242, May 2018.

Somewhere in a drawer in my house is a yellow bandana handkerchief with the cartoon image of a pirate, crossed cutlasses and bones, a skull grinning unthreateningly above them through its eye patch. The same logo can be seen on the Selle Italia saddle on my mountain bike, somewhat mud-spattered I admit and with a bit of scuffing on the corners. I’ve never worn the bandana, but have hung on to it as a historical artefact. The saddle was given to me as an ironic birthday present and hung around the bike shed for years before I got round to putting it on a bike.

The bandana and the saddle were produced during one of cycling’s most bizarre marketing drives at the back end of the 1990s, when Marco Pantani was plugged relentlessly as ‘Il Pirata’, cycling’s buccaneering mountain climber. In his piratical pomp, his team presentation took place on a mocked-up galleon, with all his team-mates wearing bandanas. There may have been parrots in attendance, and treasure chests stuffed with doubloons. Ludicrous it may all seem now, but the saddle and the bandana are the products of a more innocent era, which now looks like Italian cycling’s last gasp of glory before it faded and died.

Context is everything when looking back at events, but contexts can change dramatically. So it is that Pantani’s 1998 Giro d’Italia victory looked like one thing at the time, something else a month later and something entirely different within a year. Within half a dozen years, the way we saw the Pirate’s pink jersey was thrown up in the air again.

Let’s start with how it all looked in June 1998: this was the biggest victory for one of Italy’s biggest stars, an old-school triumph that took the delirious tifosi and ecstatic journalists back half a century to the era of Fausto Coppi. The Giro was expected to be won by the Swiss Alex Zülle, the double Vuelta winner who had transferred over the winter from the Spanish ONCE team to Festina. His arrival was seen as tacit acceptance that their French leader Richard Virenque was not Tour-winning material. The three other favourites all rode for Italian teams: Pantani was in search of his first grand tour win after an epic comeback the previous year when he had finished third in the Tour after winning the stages to Alpe d’Huez and Morzine; the defending champion Ivan Gotti was a shy little climber whose Saeco squad was split between his interests and those of the extrovert sprinter Mario Cipollini. And then there was Pavel Tonkov, a lugubrious Russian who had won the 1996 race and finished second in 1997, and who had the backing of a stellar line-up at Mapei, including the 1990 winner Gianni Bugno, who had reinvented himself as a domestique de luxe.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The race started in Nice, and Zülle took the prologue win as expected, although his tenure of the pink jersey lasted only three days, with a split in the field after a crash near the finish on stage 3 into Forte dei Marmi. Next into the maglia rosa was time triallist Serhiy Honchar, then one-day specialist Michele Bartoli, whose tenure was brief: he took the lead the day before the first mountain top finish, at Lago di Laceno in Italy’s south, where Zülle attacked, disconcerting the Italian fans by dislodging Pantani by 24 seconds. “I rode with instinct, he rode with intelligence,” was Pantani’s verdict.

Worse was to come for the Italian hero. Zülle and Festina controlled the race for the next 10 days - ceding the pink jersey to France’s Laurent Roux and Italy’s Andrea Noè for a day apiece - and Pantani crashed on the descent from Passo dello Zovo en route to Schio on stage 13. He blamed himself, saying that his plan had been to “throw himself down as if I was going to break my neck,” in an attempt to dislodge Zülle, a notoriously nervous descender who was handicapped by having to wear thick glasses.

Thanks to a stage win at Piancavallo, Pantani had reduced his deficit on his Swiss rival to just 22 seconds by the time they arrived at the time trial in Trieste, the following day, with a week’s racing remaining. But here, on the 40km test, the Festina leader looked to have taken a stranglehold on the race. Starting the time trial three minutes behind Pantani, he embarrassed the Italian by catching him and added another 26 seconds to stretch his lead to almost four minutes. Once the time keepers had done their sums - the victory was initially given to the Ukrainian Serhiy Honchar before a recalculation went Zülle’s way - he was found to have broken the record for the fastest average in a Giro time trial, clocking 53.771 kilometres per hour.

With Gotti off form and on the point of heading for home with a virus, that should have reduced the Giro to a battle between Tonkov, who had come third on the TT stage, and the Swiss, who had only to keep a lid on the others. Instead, Pantani gambled on a long-range attack on the opening stage in the Dolomites on stage 17, attacking on the Passo della Marmalada with 40 kilometres remaining along with Giuseppe Guerini, who was to become briefly famous a year later for winning the Alpe d’Huez stage of the Tour in spite of colliding with a fan wielding a camera.

The move on the 18 per cent slopes came just after the leading group had passed a graffito on the road: “Pantani, sei un mito…” - translated as, ‘you’re a myth’. It pretty much summed up the Pantani-mania that was to follow. “Two small, indomitable, tenacious, Italians. The heroes of a splendid race that harked back to old times,” read an editorial that namechecked Coppi, Bartali and Charly Gaul. Four million television viewers tuned in to watch the action unfold.

What they saw was epic. Guerini and Pantani mopping up the remnants of the day’s escape, with Zülle and Tonkov chasing fruitlessly behind them. Pantani becoming maglia rosa on the road with 15 kilometres remaining, en route to the Cima Coppi on Passo Sella, but - typically - not without a nervous moment or two: a derailed chain, a near-miss on the final descent. Later that evening, he dedicated the first pink jersey of his career to his grandmother, who had died in 1992, too early to see anything of his cycling career. He also took a call from the Italian Prime Minister Romano Prodi, who was a big cycling fan.

Though Zülle was not quite out of the picture yet – he was 61 seconds back – he clearly was not going to match Pantani on the remaining mountain stages. The threat, however, came from Tonkov, a better than average time triallist, who was 30 seconds adrift and who had taken 1:42 out of the Italian on the Trieste stage. With another 34km time trial to come on the penultimate day, Pantani had no option but to extend his lead. Instead, on the next day’s stage to Alpe di Pampeago, it was Tonkov who took the stage win and a time bonus, chipping away another three seconds on Pantani.

That left the now legendary stage to Montecampione, a marathon 237km on stage 19. Tonkov had only to mark Pantani’s every move, and the Giro would be in his pocket; Pantani had to dislodge him. Pantani’s first attack, a few kilometres into the long climb, left him with only Tonkov to deal with. It was a spectacular display, Pantani sprinting out of every corner, barely ever casting a glance at the Russian, Tonkov occasionally ceding half a bike length, but hanging on for grim death. It was a duel that captivated Italy.

The suspense lasted until three kilometres from the finish, where Pantani finally did the deed, hands on the drops of his handlebars in what was not one of his celebrated short, sharp attacks but sustained pressure to gain 57 seconds.

There remained only the Mendrisio time trial where he could still have cracked, but instead Pantani lost only five seconds. Among those who compared Pantani’s victory to one of Coppi’s feats was a name that carried immense resonance for Italian sports fans: Guido Vergani, son of Orio, one of the most celebrated journalists of the postwar era, who described Coppi’s death as “the great heron closing his wings.”

But the real romance in Pantani’s Giro stemmed from the fact that like Coppi, he had been continually beset by misfortune during his career. He had a tendency to collide with pretty much anything going, most notably an errant cat in the 1997 Giro. There had once been a funny side to his habit of falling off, but the comedy had evaporated two and a half years earlier, when it had seemed unlikely that he would ever race again, after an accident on the final descent in Milan-Turin in October 1995 had left him with an appalling fracture of the left shin.

Two years before his triumphant ride into Milan, in April 1996, the photographer Phil O’Connor and I had visited Pantani in his home town of Cesenatico; there was a sickeningly memorable moment when he rolled up his Carrera leg warmer to show us a vast lump of calcified bone in his shin, and four bullet-like holes oozing yellow pus where a Frankenstein-esque device had been attached to each side of the fracture, to ensure that the bone did not heal too quickly and thus leave him with a shortened leg.

At that point, he could not use a gear higher than 42x19, as the newly healed bone could not support any pressure. He was unable to ride out of the saddle. In July 1997, when I met him after his third place in the Tour, the wound was still releasing toxins, he said; he was still scared on descents where there was no motorbike to protect him; there were occasional flashbacks. That Giro was a comeback, then, to match others cycling had known: it wasn’t on the scale of Greg LeMond’s return from death’s door to win the 1989 Tour, but it was up there with Coppi’s recovery from a horrendous leg fracture in 1950.

By the end of July that year, Pantani’s Giro had been eclipsed by an even more impressive victory in the Tour de France, making him the only Italian since Coppi to achieve the mythical Giro-Tour double, and only the seventh cyclist in history to manage the feat. The Giro was the first half of the diptych, admittedly, but the Tour was what everyone recalled, partly because of the way Pantani had won it, with that epic, Fausto Coppi-esque move through the Alps to unseat Jan Ullrich on a rain-hit stage to Les Deux Alpes.

In the wider context, Pantani’s double was overshadowed by the fact that its second half was the “Festina Tour”, when cycling finally had its eyes opened to the EPO problem that had been lurking for years. The Pirate himself, interestingly, was not immediately seen as part of that wider problem, mainly because journalists - including me - were blinded by the fact we loved the way he raced and found the character of the man hard to resist. Good guys, charismatic, accident-prone guys, guys with a great story to tell, they couldn’t possibly cheat, could they…?

That’s why 12 months later, Pantani’s fall from grace was so massive when he was thrown off the Giro at Madonna di Campiglio after failing a haematocrit test. More devastating, in fact, was the finding of a CONI inquiry which concluded he had been using EPO when he crashed in Milan-Turin in 1995. It’s easy now to overlook the significance of this: he was Italy’s biggest sports star at the time, bar none. Forget footballers.

As I wrote in the first edition of Procycling that spring, he was the guest of honour at the 1999 Ferrari Formula One team launch, where it was apparently felt that Michael Schumacher’s image could only benefit by association.

Incredible as it may seem now, there were 13 Italian teams in the 1998 Giro. Yes, just 13 in those days before the ProTour/WorldTour existed, with only five teams coming from abroad. Fifteen of the 22 stage wins went to the home riders led by the likes of Cipollini. Pantani was at the centre of that gold rush of sponsorship and money, built though it was on a foundation of EPO and dodgy doctors that proved ultimately to be more than fragile; it was a minefield.

These days, what was cycling’s leading nation in the 1990s does not boast a single Italian registered or sponsored team in cycling’s first division, though there are Italian-managed squads backed by Bahrain and UAE. The drug busts that came later played their part, but you have to trace that dramatic decline back to the sudden moment of revelation, the immense shockwaves that came with Pantani’s precipitous fall.

And of course, within six years of his Giro-Tour double, we were all mourning Pantani with the same intensity that we had felt as we followed him up and down those French and Italian mountains. His death on Valentine’s Day in 2004 was another nail in Italian cycling’s coffin, a handful of salt rubbed in the open wound. The official story was that Pantani died of an accidental overdose of the cocaine he had used to numb his feelings since the despair of Madonna di Campiglio, the details sordid, the venue an anonymous apartment hotel in Rimini which has since been razed to the ground. That Giro now looks like the last unadulterated triumph of one of cycling’s tragic heroes, untainted at the time by uncomfortable facts, although speculation and conspiracy theories about his death still abound almost 20 years on.

So back to that Giro, the last grand tour before the crisis of Festina led to a permanent change in the way we see cycling, and - for journalists like me - the way we report on cycling. Pantani was later unmasked as a cheat and a liar, and the arguments around that are endless, but ultimately pointless. The facts are what they are, but Pantani’s unique combination of charisma and fragility, his loveable demeanour, are not changed by them.

As we’ve discovered time after time in the past two decades, when a sport has developed a morality system entirely of its own, one that bears little resemblance to the world outside, anyone can be a cheat, no matter how charismatic they are, no matter how much affection they inspire, and no matter how appealing and evocative their backstory may be. Keep that in mind, and admire Pantani for what he was in the first week of June 1998, the last Giro of the prelapsarian era.

Procycling magazine: the best writing and photography from inside the world's toughest sport. Pick up your copy now in all good newsagents and supermarkets, or get a Procycling subscription.