Gilles Delion and the road not taken

'Cycling is an ecosystem that works better without doping'

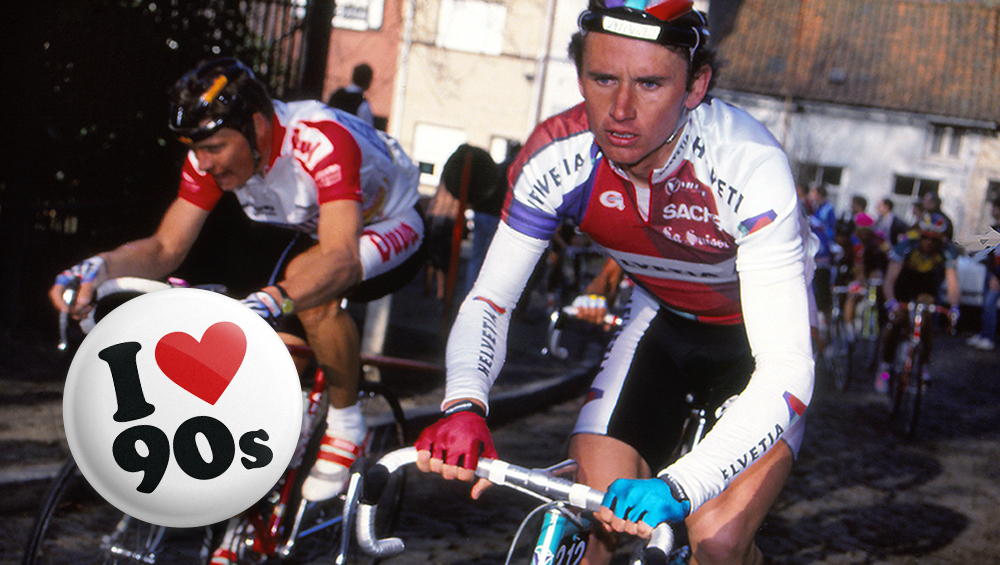

The following feature forms part of our 'I love the 90s week'

Finding a home with Koechli

After dinner on the night before the 1988 Dauphiné Libéré, Delion and the rest of the wide-eyed French national squad took a stroll outside their hotel in Avignon, to see and be seen. There are few greater thrills for the amateur rider than observing the professionals up close and off duty, but no outfit drew Delion’s attention quite like the Weinmann squad of Paul Koechli.

“I saw his team, and they were all at a glacier having an ice cream the night before the first stage. I couldn’t believe it,” Delion recalls. “Then the next day, they won the first stage, and I just thought that was brilliant.”

Niki Ruttimann’s victory that day seemed to call an entire belief system into question. Amateurs in France in the 1980s were weaned on tales of the abstinence and sacrifice demanded by overbearing men like Jean de Gribaldy or Maurice de Muer. In a world where professional cycling was viewed almost as a vocation rather than a sport, they demanded their riders to be ascetics. Koechli, on the other hand, seemed to encourage them to be human beings.

Delion rode assuredly among the professionals in that Dauphiné, placing 18th, and though he would miss out on selection for the Seoul Olympics, by the end of the summer, he had two competing offers to join the paid ranks in 1989. One was from the great Cyrille Guimard, to join the Système U squad of Laurent Fignon. The other was from Koechli. Delion took the road less travelled.

“It would be simplistic to reduce my choice just to that one episode with the ice cream, but it would have played a part,” Delion explains to Cyclingnews.

“You were coming out of an era of directives and restrictions, the De Gribaldy school, and here you had these guys eating ice cream one day and racing the next. It was another way of living cycling, and it seemed more relaxed. It was still very professional, but there was just a bit more freedom from day to day.”

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

With his greying ponytail, thin face, and wide glasses, Koechli hardly fitted the archetype of team manager as authoritarian strongman, and there was something different, too, about the culture of his team. On most squads of the era, syringes were a simple part of day-to-day life. Even if managers didn’t foist doping directly upon their riders, the prevailing atmosphere of permissiveness tended to make it difficult to resist the temptation of the needle.

At Koechli’s outfit, rebranded as Helvetia for 1989, the starting point, at least, was different.

“Koechli had a reputation for being clean and running a clean team. Sometimes a directeur sportif even might come into the toilets to check that riders weren’t trying to give themselves injections,” Delion says.

“I wouldn’t say that doping was completely non-existent on Helvetia, but doping just wasn’t a topic of conversation. Were there riders on the team who played around with doping? Perhaps, I don’t know. But doping wasn’t part of the culture of the team, and I think the large majority of the riders were clean.”

Under Koechli’s tutelage, Delion took smoothly to the professional peloton. He won the GP Lugano early in his debut season in 1989 and proceeded to showcase his climbing talent with second place overall at the Tour de Romandie.

As an amateur, Delion had never been selected for the World Championships, but with the event taking place on his doorstep in Chambery that year, a pugnacious showing at the GP Plouay earned him the nod ahead of Jean-Claude Colotti on Bernard Hinault’s team.

“I think I deserved my place in any case, but I can imagine the organiser would have been keen to have a Chambery rider who was going well at the time in the race,” Delion says.

The weekend offered an insight into life outside of Koechli’s orbit. Hinault had the aura of a champion, but was hardly cut out for the role of tactical guru. Fignon led the French challenge, but there were, Delion says, clans within the team.

On the eve of battle, Delion asked his roommate if the others were “going to take something” for the next day’s race. “Bah, like normal,” came the casual response. Still, as Greg LeMond claimed the rainbow jersey on a sodden afternoon in the Alps, Delion quietly fulfilled his supporting role. Six weeks later, he capped his maiden season with a fine second place at the Tour of Lombardy behind Tony Rominger.

There was no sophomore slump in 1990. A graceful, long-limbed rider, Delion sparkled across all terrains, but particularly when the road climbed.

“I was a good Classics rider and I was beginning to develop into a good rider in the stage races,” he says. He was a polyvalent, with only time trialling a relative weakness. Still only 23, he placed third at Tirreno-Adriatico, third at Milan-San Remo – won by a rampant Gianni Bugno – and beat Fignon to win the hilltop stage at Critérium International.

Delion, it seemed, could do it all, and in July he made his Tour de France debut, surviving the three weeks to finish 15th place overall, good enough to reach Paris as winner of the best young rider classification. The lack of a maillot blanc – the jersey went on hiatus between 1989 and 2000 – ensured that the achievement went largely unnoticed.

“To be best young rider wasn’t a great performance in itself anyway,” Delion says now. “It wasn’t that big of a deal. I was only 15th overall, whereas riders like Fignon and Hinault had won the Tour outright when they were that age.”

In the final weeks of the campaign, Delion stitched together another series of sparkling displays, finishing on the podium of Milan-Turin, the Giro del Lazio and Giro dell’Emilia.

“The team’s programme took us to Italy a lot, and the races there tended to suit me because a lot of them finished on circuits with a hill,” Delion says.

As the year drew to a close, the tapestry still needed some adornment. A big victory was lacking, and only the Tour of Lombardy remained. “I didn’t feel any pressure,” Delion says. “Just the will and the desire to win.”

Koechli’s plan of attack, unveiled the night before the start in Como, was typical. Rather than shut the race down, the men in maroon and red jerseys would seek to blow it wide open. Australian Michael Wilson were delegated to go on the offensive early, with Richard and Delion primed to bridge across. With two out of five riders in the front group after the Valcava, it was hard to argue with Koechli’s logic.

“We were always well-represented in the front group near the end of those races, because we were a team of opportunists and attackers,” Delion says.

The only glitch, at least for Delion, was that he had Richard for company.

“It wasn’t my job to ask him to ride and the other riders didn’t say anything. They probably thought he was riding that way because he was struggling, but he was always a cunning rider like that,” Delion says. “Apparently, he wrote in his book afterwards that I’d stolen the Tour of Lombardy from him, but it was the exact opposite. If he had won that Tour of Lombardy, he would have stolen it from me. I took every turn, I didn’t skip one. I deserved it.”

Later that afternoon, as the sun dipped over Monza, Delion stood atop the podium alongside Gianni Bugno, who had held off Sean Kelly to seal the UCI World Cup. There were few more stylish riders than Delion and Bugno in the peloton. It was hard to shake off the feeling that the decade just beginning might end up belonging to them.

Just as quickly, the new dawn faded

For Delion, the problems began during the winter immediately after that Lombardy victory. After struggling with illness through the off-season, Delion’s 1991 classics campaign was wiped out by a bout of mononucleosis, and, in truth, he was never the same rider again.

In the years that followed, Delion could never seem to go more than a few months without succumbing to illness. Building form was nigh-on impossible when hindered by what amounted to chronic fatigue. Occasionally the fog lifted, but such clear spells had all too short a lease. In 1992, Delion won the mountainous Classique des Alpes and beat Stephen Roche to win a stage of the Tour de France the following month. In 1994, he won the Grand Prix de l’Ouverture, but the title seemed grimly ironic. He was already nearing the end.

“I had a lot of illnesses that penalised me. I had too many physical problems. You need to train and work hard, and if you don’t do that work, you struggle. It was a period where I was too tired to train properly, that’s what happened to me,” Delion says, gently dismissing the idea that he had been rushed back into action after each illness. “You can make all sorts of suppositions and hypothetical scenarios, but if we all dealt in ifs and buts, we’d all be world champions.”

However one hypothetical scenario is difficult to shake off. Had it not been for the emergence of something as potent as EPO as the peloton’s poison of choice in the early 1990s, would Delion’s career have panned out differently?

Certainly, the public perception of Delion is that his refusal to dope ultimately ensured his potential remained untapped, but the narrative, he says, cannot be wrapped up so neatly.

“The two elements are part of it,” Delion says. “Above all, it was my health problems that hindered me but that was aggravated by the fact that greater and greater numbers of riders were using EPO. You can’t attribute my loss of competitivity to one or the other, it was a combination of the two.”

To this day, the EPO era’s patient zero remains a mystery. Nobody can quite put a date on when the artificial hormone was first introduced into cycling, and identifying a tipping point when the majority of the peloton started using EPO is equally hazardous.

For Delion, like for many outsiders, the startling Gewiss 1-2-3 at the 1994 Flèche Wallonne was the moment nebulous rumour solidified into hard fact, though the peloton had been rife with increasingly stranger things for several years at that point.

“After that Flèche Wallonne, it was obvious, but it’s difficult to take a position on doping based on any particular performance, because there will always be riders who go stronger than the others. Every strong performance is liable to be deemed suspect, and it’s difficult to define what the limits of natural performance are,” Delion says.

“That said, I did see things that made me stop and think. I’d see riders who had been in the gruppetto now leading the peloton on climbs. I remember a French sprinter leading the peloton on the Col d’Izoard, when normally he would have needed to be in a trailer to get up there.”

Delion says he remained largely shielded from the new reality in the peloton until the end of 1992, when Helvetia disbanded. He moved to Castorama, managed by Guimard, the very man he had turned down as an amateur, and though there was no systematic doping programme in place on the team, there wasn’t the same oversight as on Koechli’s set-up either.

“It was a different culture, but I really liked Guimard as a personality. He was very charismatic and he had phenomenal tactical nous,” Delion says. “I’m always surprised he was never the selector of the French national team.”

Within the bunch, Delion had by then earned a reputation as a rare rider who refused to dope, cemented by his stage winner’s press conference at the 1992 Tour, when he told the world his victory in Valkenburg was the product of “water and fruit salad.”

Such remarks can hardly have endeared him to his peers, but he didn’t suffer the kind of shunning later endured by Christophe Bassons.

“No, I didn’t have the impression that it particularly complicated my life in the peloton. I couldn’t say that there was any particular attempt to hinder me in races, and if there was, I certainly didn’t notice,” Delion says.

Delion was instead impeded in a rather more gradual fashion. After two years at Castorama, he wound up at Vincent Lavenu’s humble Chazal team in 1995. A year later, Delion was unable to find a team in France, and signed for the lowly AKI-Gipiemme squad in Italy.

“Given that I’d won Lombardy and given the capacities I had, it wasn’t normal that I couldn’t find a team,” Delion says. “I think my reputation harmed me there. I was known as a rider who didn’t take doping products at a time when they were everywhere.”

His tenure at AKI was short-lived. In the spring of 1996, EPO was undetectable and blood values went unchecked by the authorities. All around the peloton, injections were carried out blithely in hotel rooms. Cycling’s doping laws had always been loose, but now there was no order either. Struggling with the usual health problems and his morale in pieces, Delion rescinded his contract in April of 1996. He would race mountain bikes for five more years, but his road career ended before his 30th birthday.

In January 1997, as the UCI unsheathed a paper sword to fight EPO by introducing a 50 percent limit on haematocrit levels, L’Équipe ran a series of articles explaining the gravity of the situation. Delion was interviewed, and he outlined the prevalence of EPO. In keeping with the tenor of his reign before and afterwards, UCI president Hein Verbruggen dismissed Delion – and Graeme Obree, who also spoke out – as embittered losers. From the body of the peloton, there was only silence.

“When I took a public position against doping, there were other riders who were like me, who thought like me. There were other riders who didn’t take anything, only they didn’t say anything because they were afraid of losing their place on their team, or losing a race because people rode against them in the finale,” Delion says.

“They were afraid to turn their backs on the peloton. It’s a pity because when I took this strong position against doping, I found myself alone.”

Little over a year later, Delion was vindicated by events at the 1998 Tour, when the scale of the EPO epidemic was exposed as a result of the Festina Affair. No lasting remedy was applied, however, and the wound was instead dressed with the same old secrecy and denial.

The manager of the Festina team, Bruno Roussel, had been a directeur sportif at Helvetia, and even tried to sign Delion in 1995.

“I don’t know exactly what his level of responsibility was, but he paid a price for others,” Delion says. Other Helvetia alumni, such as Pascal Richard, Laurent Dufaux, Rolf Aldag and Mauro Gianetti, were later implicated in scandals: “EPO was so generalised at that point that there very few riders who weren’t taking it.”

No dwelling on the past

Delion’s future was unwritten as he crossed the finish line that afternoon in Monza, and in many respects, it remained so. Betrayed in equal measure by his own poor health and the poor governance of his sport, he remains a footnote in cycling history. Delion could have been – should have been – a contender, yet there is not the merest trace of rancour as he recounts his career over the phone from Chambery.

“I think it’s because I had these personal health problems that affected me too, so I can’t lay the blame for it all on doping. It’s not just doping that ruined my career,” Delion says. “I wasn’t a champion. I won the Tour of Lombardy and I could have won more, but I was ill.”

After finishing up as a mountain biker in 2001, Delion took a position as a commercial adviser with Bouygues Immobilier in Chambery and built himself a life outside of cycling. When he felt like going to watch a bike race, such as when the 2012 Giro d’Italia neared the French border at Cervinia, he simply went along and stood on the roadside with his family. He had no wish for a VIP pass, no desire to be feted for past glories and no need to tell a sob story.

Since 2013, Delion has been on the board of the UCI’s Professional Cycling Council, and declares himself encouraged by what he has heard, even if he expresses the need for constant vigilance.

Like many, he is unsure of mechanical doping’s reach, and he is concerned by Tramadol and therapeutic use exemptions.

“Cortisone should be completely banned,” Delion says. “You have to be watching all the time because you can never be sure of anything, but the culture and values have changed completely from before. Riders today have the fortune to operate in a healthier environment, where they can hope to win races without having to dope. Cycling is an ecosystem that works better without doping than it does with doping.”

It is tempting to wonder how far Delion might have gone, health problems or not, had his career taken place in an unpolluted ecosystem, different to that of the 1990s.

The question can never be answered, of course, and Delion isn’t given to dwelling on it. Doping culture and health concerns ruined the cyclist, but the man still endured.

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.