Getting a grip on doping

In the years since the Festina Affair, media, judicial, financial and moral pressure has been put on...

An interview with Anne Gripper, Part 2, August 3, 2007

Aside from the issues mentioned in Part I of this interview, UCI anti-doping manager Anne Gripper also discussed many other topics in an earlier chat with Cyclingnews' Shane Stokes in the run-up to the Tour de France. This conversation covered important areas such as the different philosophies emerging within pro teams, DNA and Operación Puerto, the Men in Black and out of competition testing, the relationship between the UCI and WADA and the fact that innocent riders are now no longer willing to stay quiet about cheating in the sport.

In the years since the Festina Affair, media, judicial, financial and moral pressure has been put on teams and riders not to dope. 2006 is seen as a turning point of sorts, as with the Operación Puerto and Floyd Landis affairs the previously-existing Omerta [code of silence] began to be challenged. More and more riders recognised the bleak future which was in store for cycling if such things continued. There has consequently been an increasing number of people stressing the need for change.

In addition, the Puerto affair was followed by the news that several teams were going to set up strict anti-doping structures which, in addition to a toughened code of ethics, further moved things forward. Jan Ullrich's T-Mobile and Ivan Basso's CSC were the teams of Puerto's most high-profile riders to be excluded from the 2006 Tour and both consequently had a lot to lose. They were under a lot of pressure from the sponsors, the media and the public and for this reason a new start was needed, and many changes introduced. The riders concerned were fired, restructurings took place and large sums of money were set aside by both to fund external, independent testing to be run on the riders.

Both teams have become strong proponents of a clean sport, as has the Slipstream Chipotle team of Jonathan Vaughters It requires its riders to undergo regular, advanced testing in order to prove to onlookers that there is nothing to hide. A number of French teams plus the German Gerolsteiner squad have also been very outspoken.

Some others, however, are either being less transparent or are actively dragging their heels. It seems that the Puerto message still hasn't sunk home for some, who are happy to continue turning a blind eye to doping, or worse.

"There are some teams who've really embraced the whole anti-doping issue and take on responsibility for it themselves," said Gripper during the Tour de Suisse. "They have done two major things. They have put in place very strong anti-doping programmes that they are funding and they are organising themselves, but they have also really made strong attempts to change the culture and to make sure that the environment in which the riders are living and training is free from the temptation and the pressure to dope. They are focusing much more on good, hard, clean training and they put everything in the environment to enable the riders to do that.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"Those teams are also very good at being really conscious about where the riders are going when they are not with the team. Of knowing if they are making strange trips to Spain, or things like that. I guess at this stage some teams still have a very narrow view of what their responsibility is towards their riders; we are encouraging them that it is them who can change the culture. Pat [McQuaid] has made it clear that they have got 28 to 30 riders [in their care], and that they should monitor them and really make sure that they know what they are doing. He also called on them to ensure that their riders only really use doctors and other people who are actually with the team. In other words, that they didn't go outside for any other training or medical services.

"Basically, that's the one thing that we are asking the teams to do - to be much more like vigilant about their riders. They maybe don't have to go as far as having their own in-house anti-doping programme like some others are doing, but they can certainly help to change the culture."

CSC and T-Mobile are paying several hundred euros to the respective external bodies who run their internal tests. Gripper recognises that other teams may not have this budget, but feels that the UCI's own anti-doping programme can fill the gaps.

"Our 100% Against Doping programme gives them an opportunity to contribute to an anti-doping programme without having to source all their own expertise. They can make their financial contribution, they can publicly support the programme. They can also do additional things, such as providing us with more information about their riders whereabouts [for out of competition testing]. It is a good strategy for them to be able to say, 'well, we are taking this issue seriously and we are co-operating'."

As mentioned in Part I of this feature, the Riders' Commitment for a Clean Cycling also increases leverage on teams and riders to train and compete without doping. This was launched on June 19 and required riders to sign a pledge that they were clean, that they were not involved in Operación Puerto or any other doping case, that they would provide a DNA sample if required and that they would undertake to pay a year's salary if they were found to have engaged in doping practices. For Gripper, this is an important development.

"It is really a tool for us and also for the teams to use," she said in the days after that launch. "If there are some of their riders who don't want to sign it, then it is a chance to ask them 'well, why - why don't you want to sign?' This will enable them to have some good discussions with the riders. And the same for a Christian [Prudhomme] and the other race organisers, he can ask, 'well, what it is about this that you can't sign? If you want to ride in the Tour de France, I would expect you to be able to say, 'yes, I wasn't involved in Puerto, and I am not involved another any other doping activities.'"

DNA and Puerto

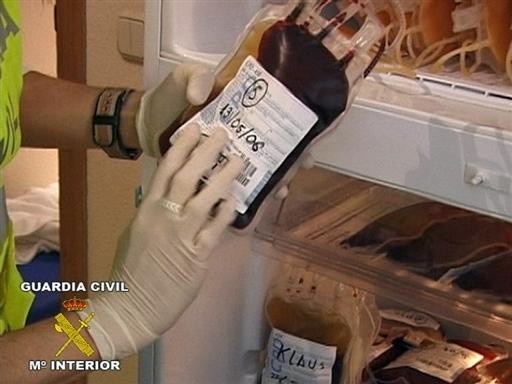

Prior to the Tour de France, Cyclingnews asked Gripper if the UCI was planning on doing DNA testing to determine if any of the riders taking part had worked with Eufemiano Fuentes. The Operación Puerto affair saw many bags of blood being found in Fuentes' clinic in Madrid; such testing would help determine which riders were involved. However she explained that there was a delay with the Spanish authorities processing of the case, so any such comparisons could only be done at such time as the blood bags (or DNA from them) was released for such testing. There's no indication yet as to when this might be.

"We are really imploring the Spanish authorities to give us the opportunity to match those bags of blood to any riders that are happy to provide the DNA. The issue with DNA is that we are not going to keep a bank of DNA samples or long bits of paper with DNA records on it. Ethically, you can't do that. But it is a very limited use of DNA, a one-off use for the purposes of matching and identification.

She said that it would not be the case that every rider who signs up will have their DNA compared with the blood bags. "We will target riders. And certainly some of the riders who have been linked with Puerto have been saying for the last nine months that we can have their DNA, that they really want to get out of this mess. Those riders are just really keen to give their DNA. The only riders we will use DNA for now are those who are linked to Operación Puerto. Then if something happens in the future which involves human samples, well then we would may seek it again. But it is for this case."

The UCI are still examining the additional information that they got earlier this year on the Puerto case. They have a Spanish lawyer in Madrid and have also engaged a Spanish-speaking lawyer in Switzerland. However, Gripper said that the file needs a lot of work to translate and piece everything together, so it is a slow process. In addition, the UCI is still waiting for a decision from Spanish legal authorities as to whether they will reopen the case, if the courts will still continue with criminal proceedings, or if the UCI can now use the information and impose its own sanctions.

The case has clearly been a great source of frustration; not just to the UCI, but also to riders who were not involved but want to see sanctions applied on those who cheated, and also from any competitors who have been accused but who want to clear their names.

Men in Black

Another issue which caught public and media attention in June was the Men in Black situation. This referred to riders who the UCI felt were behaving strangely, going to certain locations and not wearing their normal team gear. The Astana team were quick to deny that they were involved, saying that its riders sometimes wore non-team clothing in the South of France so as not to attract a lot of attention from fans.

When Cyclingnews spoke to Gripper she didn't specify who that phrase referred to, but gave the impression that she was not talking about France but locations much further afield. One possible conclusion is that the riders concerned were trying to remain incognito in far-off locations in order to avoid the greatly-expanded out of competition testing.

Such testing is important as it tries to catch doping athletes unawares, seeking to nab them at the very time that they have traces of the doping products in their system. Gripper told Cyclingnews that the UCI has a list of top riders in what they call the registered testing pool, drawing from all of the Olympic disciplines of road, track and BMX.

"One of the criteria is the top 50 men on the road, based on the rankings. And then there are another 20 ProTour riders who are on there for other reasons. Either they have got a certificate for high haematocrit, they are under suspicion or there is a whole range of other reasons. So those 70 riders are required to give us daily whereabouts information, and on the most part they are good. But the riders who are more difficult for us to test are those who aren't required to do that, and more and more we are going to be relying on the teams to ensure that their riders do provide their whereabouts.

"The comments about the Men in Black were just one example… when we get information, it is about strange behaviours, either in training or in competition. That is what we act on. And when we hear about riders going off to other parts of the world to do intense training, maybe where there is not the opportunity to be tested, well then that raises alarm bells as well." Gripper didn't name names, but now, several weeks after she gave that description, a situation like that which related to Michael Rasmusssen would seem to fit right in.

"We want riders to know that there is no longer any sort of haven. This year, the 100% Against Doping is the first time that we have really organised a properly thought-out out of competition, unannounced programme. We want to make it clear that it is not just in Europe that they can be tested, they can be tested anywhere in the world. And if they do take themselves off to unusual places to train, we will find them there as well!"

One important training and racing test is the blood volume examination. This can determine if a rider has received a transfusion, either of their own blood or of someone else's. While the hematocrit screening seeks to determine the concentration of red blood cells, the volume test measures the total amount of blood in the body. The T-Mobile team have introduced such testing this year and it is a vital weapon in their fight against doping. Gripper says that while the test plays a very important role, she feels that more needs to be done before it can be used by the world governing body. "It is some way off being considered as a validated anti-doping test yet, but the more we can contribute to research, then the closer we will get making it validated."

She said that they have to look for greater certainty due to their role in the sport. "We need to wait until it is peer reviewed because we are an authorised testing agency. T-Mobile is like a commercial entity with riders' contracts of employment, so they can manage those contracts of employment in the way that they choose to. We have to very much stick to the approved anti-doping detection methods. But once we can bring it in, we will look at doing so." It would be an important step; once that happens, combining that test with other blood analyses would seem to ensure that homologous and autologous transfusions would be a thing of the past. And particularly if the testing is done closer to the start time of races.

UCI-WADA relationship

In recent days WADA chairman Dick Pound attacked cycling yet again, saying that the current testing procedures are inadequate. This is despite the fact that the UCI conducted 180 out-of-competition tests before the Tour de France, 400 pre-stage blood screens, 140 post-stage urine tests and 40 post-stage blood controls. The UCI says that some of the samples have also "been kept for later analysis using methods which are still being developed."

It's hard to understand Pound's point, particularly as cycling is already doing more testing than almost every other sport. Gripper said that while relations with Pound may be strained, the opposite is true for the agency he works for.

"To be honest, the relationship between the UCI and WADA has always been very good," she said in June. "The issue is actually between Dick Pound and [former UCI president] Hein Verbruggen, and that goes back 20 years. It is unfortunate that it is played out in the media as a WADA-versus-UCI issue when it is not at all that. I have a great relationship with WADA as do all my staff who work in anti-doping, and I think that they genuinely believe that the UCI is now one of the leading international federations in the things that we are doing. Pat [McQuaid] also has a good relationship with David Howman, the WADA director general. They are in constant communication. So it [cycling and WADA – ed.] is not the bad relationship that it sometimes is made out to be."

WADA is currently working on revising its Code, which has provided a guideline for drug testing across a huge range of Olympic sports. Cycling's efforts to stamp out doping has included many new methods which other sports do not currently employ. Given Pound's criticism, it's ironic that the UCI may play a big role in helping shape the new code.

"We have already provided quite a lot of input," said Gripper, when asked if the UCI anti-doping programme would have an influence. "WADA is in the process of revising the World anti-doping code at the moment. We are into the second or maybe the third consultation phase. WADA are very at good consulting, they get broad involvement. We provide ours through Philippe Verbiest, he is our legal counsel, and he is very well respected by them. So Mario [Zorloli, UCI chief medial officer] and I talk with him about what we think should be in the Code. And we also provide quite a bit of input into the international standard for testing.

"They have certainly taken on quite a few of our suggestions in the previous phase of the revision of the code. WADA is very good at listening to what the key stakeholders think, and I think the UCI is a key stakeholder."

The new version of the Code will be voted on in Madrid in November and it would clearly be good – and more equitable – if more sports applied the same standard of testing as the UCI does. Cycling is making big efforts to tackle doping and the resulting positive cases result in undeniable negative publicity. Other sports, meanwhile, are doing far less testing and therefore making fewer of these dark headlines.

Omerta crumbling

One major change in the sport is that more and more riders are becoming outspoken about the need for doping to stop. The message appears to be sinking in that there is a very bleak future for the sport unless things change. While the law of silence ruled ten years ago, this is less and less the case nowadays. Gripper revealed in June that there is also important feedback from within the peloton, which can help in working out areas to be focussed upon.

"We don't have an official hotline around like that, like some countries do…that is something that we could possibly consider, though. But we do have riders who now and then say that they have something to tell us. There have been some who have offered us information which is really useful, so it's great to get some good information from the field.

"Somebody asked me the other day if I thought was possible to win the Tour de France without doping. I reckon this year it is becoming much more possible than it has ever been before, because of the screening, because of the sense that the risks are much higher now. There are risks of being tested before the event, there are risks of losing your 2007 salary, and for me doping always has that balance between benefits and risk. I think that for a lot of people the benefits have been higher than the risks, but what we have to do is just make sure the risks are bit higher.

"I don't think that riders are any more intrinsically ethical than they were 10 years ago, but that concept of things being perhaps just that little bit too risky now because the detection methods are better, there is more testing, and they stand to lose more. That might just tip the balance a little bit to deter them from doing it."

Riders protesting against giving their DNA often complain about their rights being violated. However others counter that while that argument might apply in a literal sense, a clean athlete who has nothing to hide is far better served by openness and by doing anything that helps the anti-doping fight. Where's the justice in losing prize money, victories and a better contract to riders who cut corners?

"I always say that the burden of this whole thing about having to be tested at the end of a race and having somebody knocking on your door, and having to fill in the whereabouts forms is a huge burden that is borne by predominantly clean athletes for the sake of a few who are doing the wrong thing," acknowledges Gripper. "This was particularly the case in my former role where I was dealing with 65 sports…I always said that 95% of athletes were clean there. In cycling it may not be such a high proportion at the moment - we will eventually move there - but it is again the clean riders who pay such a big burden. They make a big sacrifice as regards their time and the inconvenience of it.

"You know, I reckon that finishing a race and then having to trudge off to doping control can really put a downer on things. Yet most riders would say 'yes, it is a hassle, but I know we have to do it'. I think it is really important that we remain sensitive to the fact that clean riders are involved, that we are doing it for them rather than to them. To always be quite sensitive to their rights and treat them with respect."