Five key stages of the Vuelta a España 2022

Race co-designer and former pro Fernando Escartin lifts the lid on Vuelta route

The 2022 Vuelta a España gets underway in Utrecht, Holland, on Friday August 19 and concludes in Madrid, Spain, on September 11 after three weeks of racing.

The 21 stages contain a variety of challenges, from two types of time trial to a customarily large helping of uphill finishes.

To take us through the most important days in the battle for the overall title, we've enlisted the help of Fernando Escartín, twice a podium finisher at the Vuelta in the 1990s and now part of the route design team at the Spanish Grand Tour.

Escartín offers the inside line on the time trials and the biggest mountain stages, explaining how the the race for the red jersey could go down to the wire.

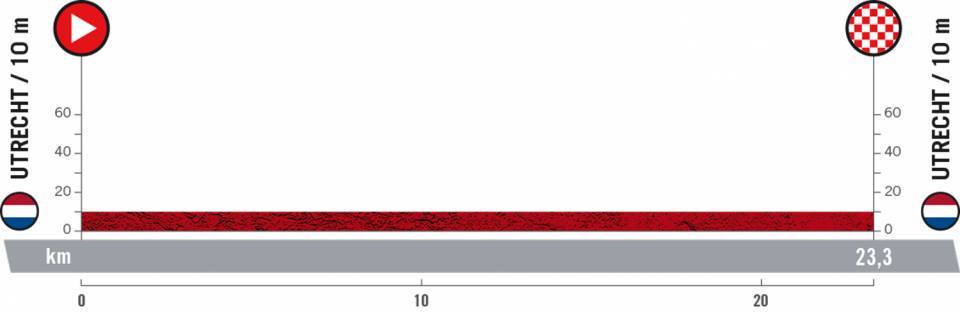

Stage 1: Utrecht > Utrecht, 23km (TTT)

'A blast from the past'

Three years have passed since any Grand Tour last held a team time trial, the most recent being the Vuelta a España back in September 2019. Fortunately, the Vuelta continues to maintain the tradition of TTTs, a speciality much liked by fans and regrettably lacking both from the Giro d’Italia since Orica-GreenEdge won at Sanremo in 2015, and the Tour de France since Jumbo-Visma took an important victory on home soil in July 2019.

So the opportunity to witness a full-scale Grand Tour TTT is definitely not one to miss - and particularly when the Vuelta’s TTT could have an important impact on the overall, right from the gun.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

That’s because the course is nearly twice as long as the 2019 Vuelta's 13-kilometre circuit in Torrevieja. Furthermore, as the third Grand Tour of the year and with the end of the season almost in sight, it can be a struggle for teams to find a full line-up of riders who are in form, ones who are specialists against the clock.

A team time trial so early in the race will ruthlessly expose any such weaknesses.

It barely matters, in fact, that the Utrecht course is completely flat, with virtually no technical sections and a low risk of strong winds to blast squads apart. In a Vuelta TTT, the risk of a team falling apart steepens far more sharply with each equivalent kilometre than in, say, the Giro or Tour. All of which will virtually guarantee a hugely interesting and potentially significant opening chapter to the Vuelta.

ESCARTÍN SAYS

OK, there won’t be huge gaps between the strongest teams. However, say a top favourite turns up with a weak squad to back them, they can easily lose a minute or more on such a relatively long course.

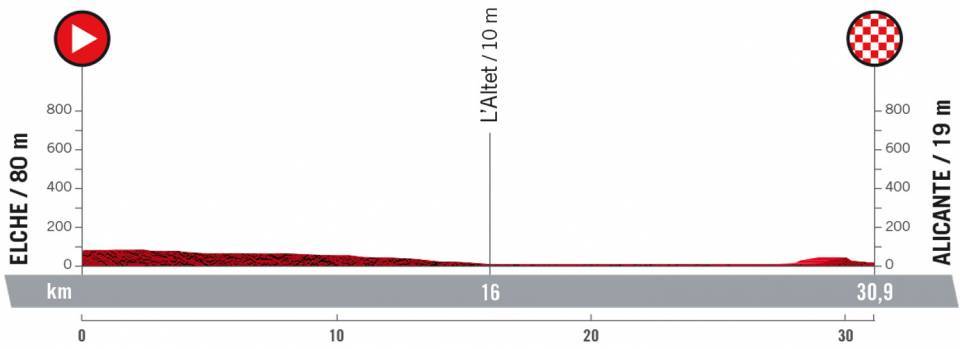

Stage 10: Elche > Alicante, 31.1km (ITT)

'A potential game changer'

During the 2022 Vuelta presentation, Enric Mas (Movistar) told Cyclingnews that he thought the organisers’ decision to place the race’s one individual time trial mid-way through the event represented a major game-changer. And Escartín agrees, 100 per cent.

This largely flat 31.1km test is positioned in the notorious pitfall after the first rest day, and ahead of two weeks largely dominated by mountains, where the pure climbers will be forced to come out to try and recoup their losses.

As Escartín points out, it's getting harder and harder for climbers to make a significant difference in the mountain stages, which also renders the ITT all the more more important.

As for how big those gaps could be in Alicante, the flat well-surfaced roads and the possibility of wind by the coast favours the big rouleurs and disadvantages the climbers even more. What's more, it's largely open road and it's only in Alicante itself, where there are a series of bends and roundabouts, that it gets more technical.

Could the Vuelta GC end up being completely decided, though, by such a demanding course? That was the case in 2019, the last time there was a mid-race TT, where Primož Roglič pulverized the entire field. The organisers are hoping that, with plenty of uphill finishes to come, this stage will merely set the scene for the direct battle to come.

ESCARTÍN SAYS

For one thing, the TT comes straight after a rest day and for some riders that juxtaposition represents a real problem, so that will automatically make it more interesting.

On top of that, our TT consists of a pretty long effort on flat roads, and the second half is on exposed roads, all of which will make the climbers suffer. However, by putting the TT in the middle of the Vuelta, the climbers will have plenty of chances in the mountains that come afterwards to recoup their losses.

Between the top TT specialists among the GC favourites, the differences probably won’t be more than 15 or 30 seconds. But for a climber, over 30 kilometres you can lose 90 seconds to a Roglič kind of rider really easily. And that’s at a minimum.

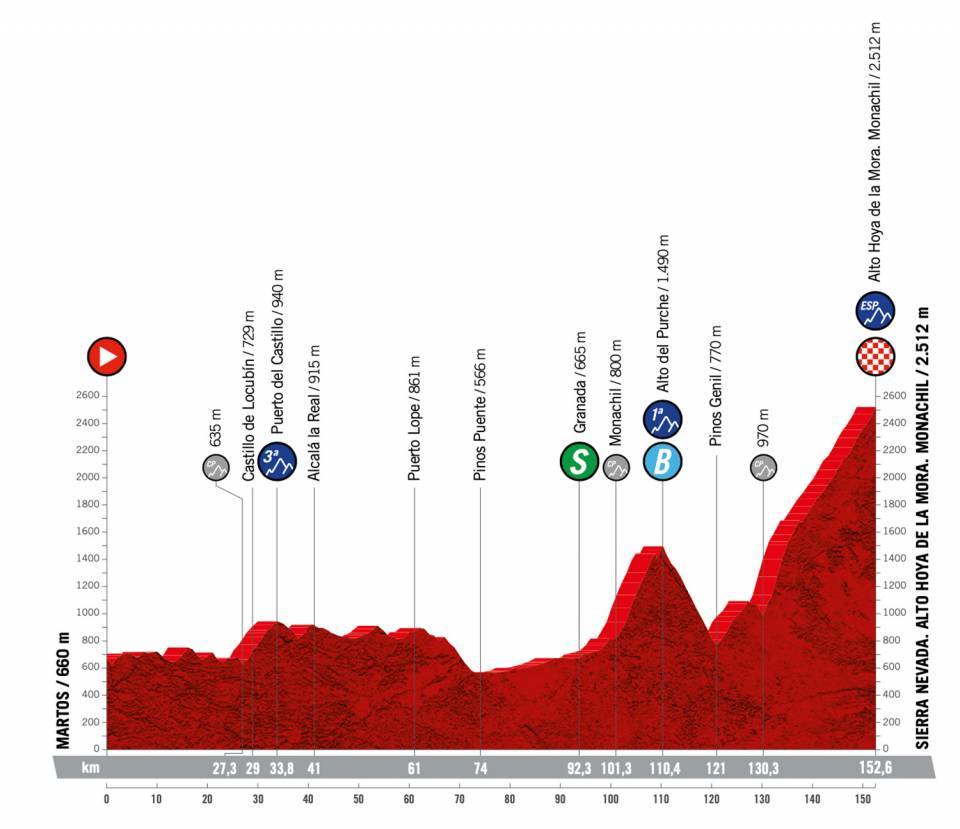

Stage 15: Martos > Sierra Nevada, 148.1km

'Hitting the heights'

The 2022 Vuelta route contains nine uphill finishes but this one towers above all others. The journey up through the Sierra Nevada is the only horst-catégorie ascent of the entire race, and the only time it rises higher than 2,000 metres above sea level.

What lies in store is only made more difficult by what will have gone before in the second week. Stage 12 - quite apart from the potential early crosswinds on the Mediterranean coast - features the ferociously long 20-kilometre ascent of Peñas Blancas - 4km more than in 2013, when it was last used. And then stage 14, just 24 hours before Sierra Nevada, finishes on one of Andalucia’s toughest single climbs, La Pandera in Jaén, with long stretches containing double-digit gradients and a very narrow, rough road to the former military base at the summit.

All this comes before Sierra Nevada itself, on a day which packs more than 4,000 metres of vertical climbing into just 153 kilometres. The route tackles the Alto del Purche, made to look like a pimple on the route profile despite its category-1 status.

And then it's over to the monster climb up the Alto Hoya de la Mora. This was last scaled in 2017, but from the other side, whereas then 2022 route is by far the hardest ascent possible of the various ways up the Sierra Nevada.

Factor in the altitude and the 35 degree heat - 40 degrees in the valleys - that usually predominates in Andalucía at that time of year, and the potential for a major mountain shake-up is very high indeed.

ESCARTÍN SAYS

There’s been a lot of stuff on social media claiming there’s no really hard mountain stage in the 2022 Vuelta, but I think people are seriously underestimating the damage Sierra Nevada could do.

This year we’ve switched things around and it’s got a lot of tough moments. Firstly there’s the Alto del Purche, a very difficult first-category climb. Then we drop down on the shortest route possible to the foot of Hazallanas. Finally, rather than go up the usual road to the ski station, we’re going up the old back road to the top, which is shorter, but far harder, and it should see much bigger differences emerge when someone attacks.

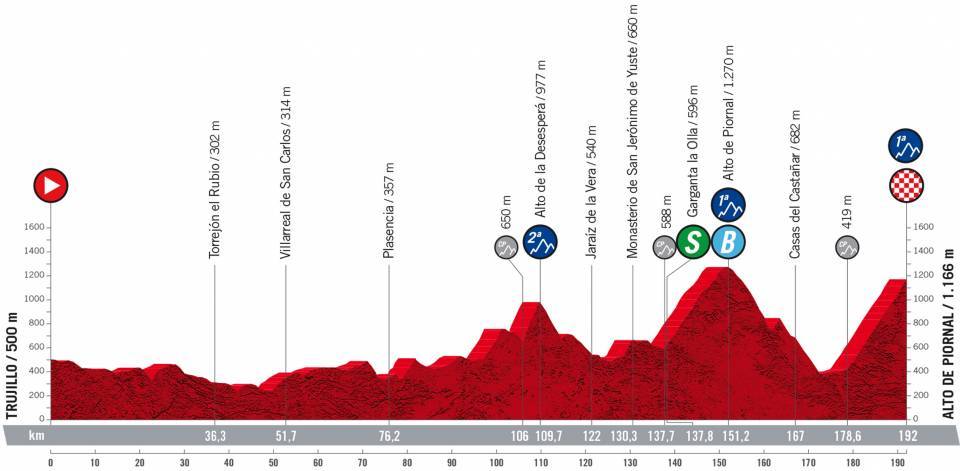

Stage 18: Trujillo > El Piornal, 190km

'A major pitfall'

Alejandro Valverde will be among the very few riders in the current peloton who were also around when the Vuelta last tackled the first-category climb of El Piornal. That was back in 2006 and before that in 2004, both times en route to the Covatilla summit finish.

Luis León Sánchez was also around for the 2006 ascent but aside from that pair, even fewer riders would be able to put El Piornal on a map. That’s essentially because El Piornal is situated in one of the most remote areas of western Spain in the border region of Extremadura, an area the Vuelta rarely visits, with last year being a big exception to that unwritten rule.

After a heavy second week, the final week is a fair but lighter but the the Piornal, being such an unfamiliar climb, could well help turn the eighth of the Vuelta’s nine summit finishes into one of the race’s key days.

ESCARTÍN SAYS

It’s not steep, but it’s relentless. There are at least three different ways of going up it and this year we’re doing all of them, including the same side the Vuelta went up in 2004, past the monastery of Yuste.

Coming late in the Vuelta, when riders are tired, it’d be easy to get caught out. The final climb isn’t so steep, but it’s 15 kilometres long and after all we’ve had before, it’s sure to catch somebody out.

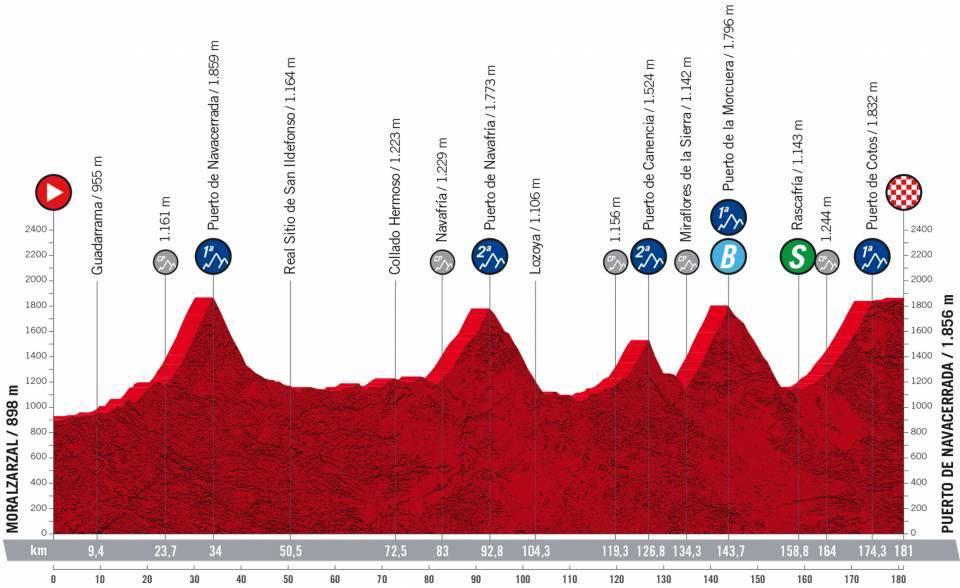

Stage 20: Moralzarzal > Puerto de Navacerrada, 175.5km

'Last-gasp drama'

In one sense, it’s hard to understand why the Sierras of Madrid have produced big surprises in the Vuelta a España GC. None of the climbs in the area are particularly long or steep, almost all of them are exceptionally well surfaced, and, as one local amateur (who understandably is not willing to be named) who has ascended them countless times tells Cyclingnews: "If you tackle them one by one, they’re all pretty bland and disappointingly short."

But that is to fail to appreciate one key factor - that the climbs are packed together, making for no room for recovery. Plus, given they’re almost always part of the third week of racing, riders are on their last legs towards the end of the season and those unhappy with their positions will be starting to adopt 'do or die' attitudes.

The Vuelta is littered with the history of leaders who had been strong throughout the majority of the mountain stages, but who suddenly found the Cotos, the Navacerrada and the Morcuera climbs, almost within sight of the Spanish capital, impossible to handle.

It’s important to remember that in 2015, the most recent example of a last-minute debacle on the sierras of Madrid, Fabio Aru’s ousting of Tom Dumoulin from the lead was at least in part due to his lack of a strong team, just as it was with Philippa York back in 1985 when Pedro Delgado snatched a lead that seemed all but unassailable.

ESCARTÍN SAYS

The Sierras of Madrid have become a stage where something always happens. Do you remember in 2015 when Aru managed to drop Dumoulin and win the Vuelta? That was because he attacked on the Morcuera, two climbs out, just like we’ve got on this year on stage 20, and in 2015 Astana had played their hand brilliantly by placing riders up the road ahead for Aru to bridge across and use to gain more time on Dumoulin.

Many riders will have nothing to lose, they know they’re on the point of finishing of the race, so they like to go flat out just to see what happens.vIt would be very hard to beat a strong team on a stage like that, but if the leader’s team isn’t that strong, and you send riders ahead, the Sierras easily becomes a stage where a lot can happen. Because the climbs are so close together, the stage doesn’t just test a leader; it tests a team as well.

It’s going to make for a fascinating final day of full-on racing in a Vuelta which perhaps doesn’t have too many of the big-name climbs like in other years, but where there are plenty of opportunities, right from that tough first week through the Basque Country, Cantabria and Asturias through to Madrid.

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.