Farewell to 'The Legend' of American cycling

US racer John Sinibaldi, an Olympian at the 1932 and 1936 Games, died last week. Les Woodland looks...

Tales from the peloton, January 18, 2006

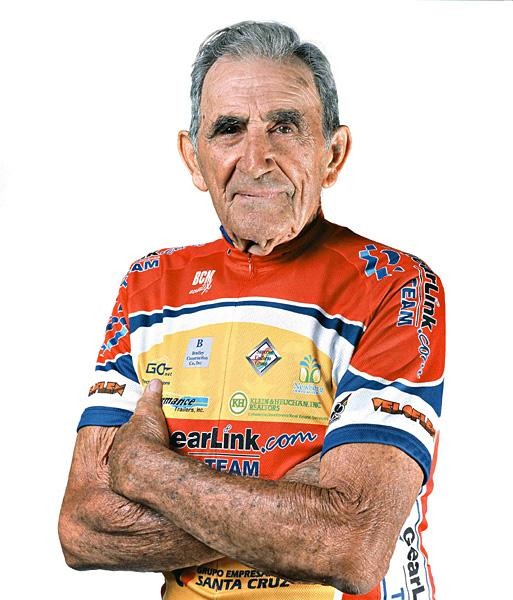

US racer John Sinibaldi, an Olympian at the 1932 and 1936 Games, died last week. Les Woodland looks back at the career of a rider who kept racing all the way through his long life and was known to all as 'The Legend'.

The American comedian George Burns used to have a good line. When TV hosts said it was good of him to be on their show, he'd raise an eyebrow and say: "At my age, it's good to be anywhere."

John Sinibaldi probably smiled at that as well. In one of his last interviews, he said quietly: "I'd like to live to be 100… but I'm not promising anything."

Well, George Burns made it. John Sinibaldi died on January 10. He was 92.

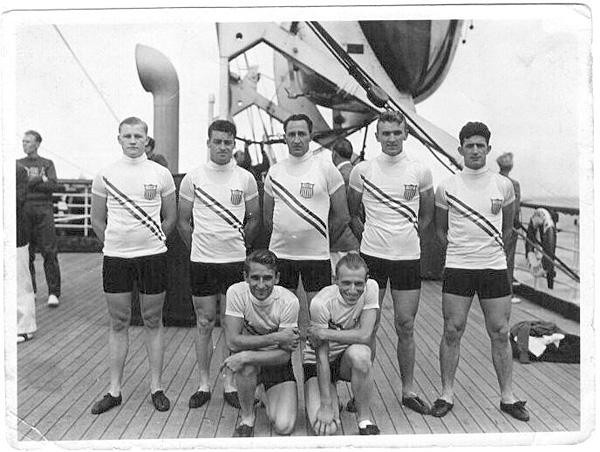

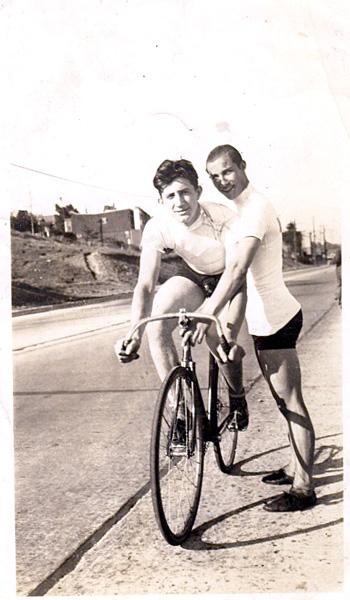

And so? John Sinibaldi was one of cycling's last remaining connections with the notorious Hitler Olympics of 1936, having already ridden the Los Angeles Games of 1932. Nothing much came of either - he came down with food poisoning at the first and crashed in the second. But for many people, that'd have been enough. A shrug, a smile, a good tale told over a pint of beer. "Did I ever tell you about the day I saw Hitler in Berlin? I did? Well, let me tell you again anyway…"

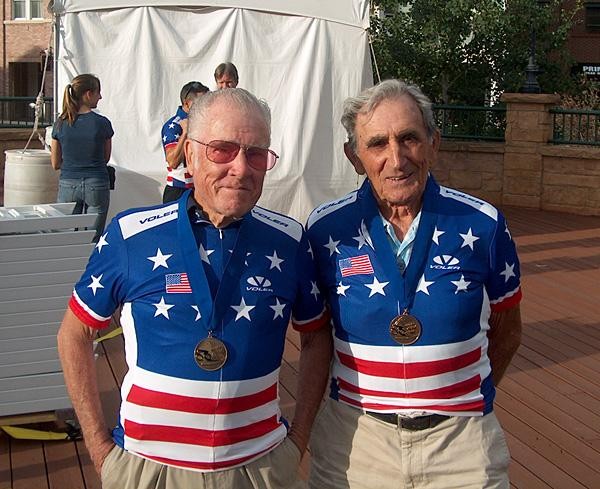

No, Sinibaldi's career was somewhat on the right side of different. This was a man who set an American 100km record that lasted 50 years. It was 2:25:09. At 80, he had five national championship jerseys for riders of his age. When he died on January 10, he was the oldest man in America to have a racing licence. Probably the oldest man in the world. At 91, he travelled to Utah from Florida to try for his 18th national time-trial championship.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

To put this in perspective, Sinibaldi had moved to Florida from New Jersey when he retired in 1975. He was a pensioner when Tyler Hamilton and Alexandre Vinokourov were only two years old. And when he wasn't racing, he was still just riding: 60km a day, 12,000km a year, 25km/h. The only real victim to age was his hearing. Even his hair hadn't turned totally grey. But in the end it was lung cancer that took him away, after a cycling career that lasted 77 years. If I tell you that in America they called him "The Legend", you won't be that surprised.

You want to live the same life? Sinibaldi's advice was to ride your bike, eat vegetables, walk barefoot when you can ("shoes will give you foot fungus in this humidity"), steer clear of television but revel in the music of Schubert. And stay in love. His wife Betty died five years before him. They'd been married for 50 years. If you called Sinibaldi's house in St Petersburg and got the answering machine, it was still Betty's voice that you heard.

The other trick was to get up at 5am, do the crossword to keep your brain going, ride at sunrise and then come back for a second breakfast and some gardening of figs, oranges and bananas. That and to drive a car as little as possible. A Ford he bought in 1988 still had fewer than 90,000km on it a decade and a half later.

And those two Olympic Games? Well, Los Angeles was the one that mattered to him. It was on home ground and America needed a party to lift itself from the Depression. So did the world. There wasn't the cash to send athletes across oceans to have fun in the sun so Los Angeles had to promise cheap fares, free food and free accommodation. The idea of an Olympic Village was born.

But Sinibaldi used to shrug. "I don't know what happened," he said of what should have been his greatest moment. "I drank something that didn't agree with me and it made me sick." End of story. What he didn't mention, unless you pushed him, was that three years earlier a horrendous bike crash had wrecked his spine and put him in hospital for a year. Spinal surgery was still primitive - the important if sad developments of wartime medicine were still to come - and the forecast was that he would never walk again. Two years after hobbling out of his hospital ward, he was an Olympic athlete.

Four years later he went to Berlin, where he remembered Hitler's strutting and the sound of a voice that the world was going to know well. He recalled Jesse Owens, the American long-jumper whom legend says (but history doesn't confirm) that Hitler snubbed for his colour.

Yet of his own Games, there was once more just disappointment.

"I felt strong," he reminisced decades afterwards as he walked barefoot in the garden (he once said that he'd choose it over his bike if he had to). "I had a couple of bad falls but I kept getting up. I was ahead near the end, when my rear wheel collapsed. I went down. That was it. Oh well… What are you going to do?"

Sinibaldi might have ridden the 1940 and 1944 Games had they not been cancelled for war. Sixteen years after his first Olympics, he set about qualifying for London in 1948. He was almost 35 and still working as a sheet metal worker, the job he'd had since growing up in Brooklyn and New Jersey. Every bit the amateur under anybody's definition, he made it as far as the regional rounds.

His medals, his records, his jerseys, his accomplishments, they were all too many to mention. There were kids who saw this old man riding and racing with other old men and perhaps they didn't quite suppress a little sneer, a little snigger.

"I'd never want to be like that," they'd say. Whereas, had they known, of course, to be like that was all they could have dreamed of.

John Sinibaldi, b. October 2, 1913, d. January 10, 2006.