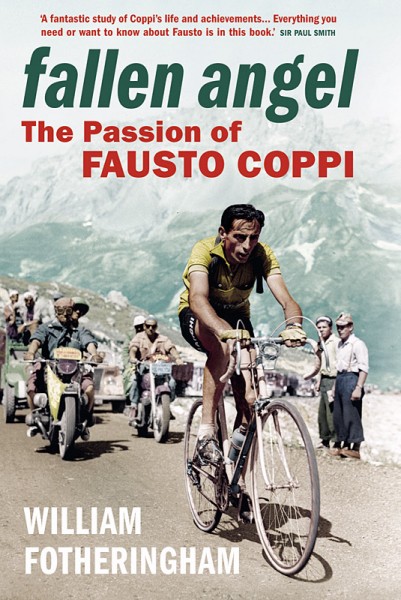

Fallen Angel: The Passion of Fausto Coppi

Voted the most popular Italian sportsman of the twentieth century, Fausto Coppi was the campionissimo – champion of cycling champions.

The greatest cyclist of the immediate postwar years, Coppi’s scandalous divorce and controversial death convulsed Italy in the 1950s and were still making headlines half a century later. A new book by William Fotheringham, "Fallen Angel: The Passion of Fausto Coppi", provides the definitive English-language account of Coppi's life off and on the bike, including this excerpt for Cyclingnews about Coppi's tumultuous 1949 Tour de France.

After Bartali had won the 1948 Tour and taken seven stage wins along the way, Coppi had told his gregario Ettore Milano that if he didn't win the 1949 Tour he would give up - he was sick, he said of hearing people talking about Bartali's win on the radio. In the event he came within an ace of ignominious failure. Just five days after the race began, he was standing by a roadside in the depths of Normandy, holding a broken bike, and asking plaintively if he could go home. It was the greatest crisis of his career, with his vulnerable side brutally exposed. The most dominant cyclist of that generation was also a fragile man who was easily destabilised.

Coppi had begun his Tour with a tour of his own, a trip around the sights of Paris on his bike. By stage five, which ran over 293 kilometres from Rouen to Saint Malo in blazing heat, the Italians were not showing well; both Coppi and Bartali were 18 minutes behind the race leader, the Frenchman Jacques Marinelli. But on that day, Binda ordered his Italians to go on the attack, and Coppi worked his way into what looked like the stage-winning escape. Best of all, he left Bartali well behind him, in a tactical fix: the older man could not set up a chase, because he could not ride against his own team mate.

As the race passed through the village of Mouen, with 100 miles remaining to the finish and the lead over the peloton already 10 minutes, disaster struck. Marinelli reached for a bottle that was being held out to him by a spectator, he wobbled and fell, taking Coppi with him and entangling both their bikes. The Italian's machine was a broken wreck: forks twisted, tyre forced off the back wheel, front wheel broken, the chain in the spokes. That should have mattered little: showing considerable foresight, Binda had asked the Tour organisers to allow him a second team car to provide service in the event of his riders having mechanical problems, on the grounds that he had two leaders, who might be in different places on the road.

So there was a car behind Coppi, and in it was his Bianchi directeur sportif, Tragella, who was on the Tour as Binda's assistant. But the only spare bike Tragella had was too small. Coppi's spare was with Binda, who had stopped at the feeding zone in order to ensure Bartali got his lunch. No less than seven minutes had passed by the time Binda caught up, to find Coppi and Tragella standing by the roadside, looking as he put it, "like two dogs that have been beaten with sticks". Coppi was certain that his race was over.

It was down to Binda and the other Italians to keep Coppi going. But merely getting him started again required Binda to use all his persuasive powers. Initially he tried compulsion, warning him that if he stopped without his permission, he would be fined. That failed and the manager resorted to white lies, telling Coppi that he himself had retired from races in this kind of situation, and had always regretted it. This was fantasy, but the situation was desperate: Coppi would not respond. Eventually, like a parent negotiating with a toddler, Binda told him that if he rode as far as the finish, he could go home the following morning, if he still wanted to.

Binda's next step was to make Bartali wait; he knew that Coppi would be stimulated by the idea that Bartali might win if he went home. Initially Bartali pedalled alongside, "alternating persuasion and insults", he recalled. "It was like talking to a wall. Then I got angry. ‘I'm going home', Fausto said. And I replied ‘my fine boy, how are you going to look to your fans? You're giving up. Goodbye glory, goodbye cash, no one will take you seriously any more. You wanted me to stay at home for this Tour and what do you do, you give up on the fifth stage?'"

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

There were a total of 18 Italians in the race, split into two teams: the national team itself (who actually wore jerseys in the red-green-white of Italy rather than the sky blue of today), and the cadetti, a team of younger riders. One of the latter, Alfredo Martini, told me that once Coppi was with the bunch again, he told the Italians not to bother chasing the leaders, although they tried several times. The race, Coppi said, was over as far as he was concerned. "He said" - and Martini suddenly lapses into the throaty Ligurian patois, half French, half Italian - "I might as well be at home under an umbrella with a cold beer."

Coppi was not even willing to stick with the peloton, and when he drifted off the back, Binda asked another Italian, Mario Ricci, to wait and escort him to the finish. There was more psychology here. Ricci was an old friend of Coppi's from his Legnano days and was also the best-placed Italian overall. Asking him to give up his own chances was a way of making Coppi aware that his status in the team was not being challenged. But even as he rode, Coppi continued to repeat that the Tour was a madhouse, and he was going home. At the finish on the St Malo outdoor cycling track, he had the body language of a man defeated: drooping shoulders, ponderous footsteps. He was almost 19 minutes behind the stage winner, Ferdi Kubler, and a massive 37 minutes behind Marinelli, and the Italian team's next job was to persuade him to stay in the race overnight. That took a concerted effort led by Binda.

It was, says former gregario Ettore Milano, a chaotic evening in the team hotel just outside St Malo: some of the team in tears, imprecations and curses flying through the air. Milano told me: "We said to him, ‘Look mate, we are at war here, we will go on to the end. We don't want to be disrespectful, [pulling out] is not just like being cheated on by your wife, it's like having your balls cut off.' What could we do but joke? We all made him go on. We got round him and made him continue in the race." Milano also pointed out to Coppi that he was marrying shortly and needed money. If Coppi went home, he would have no wedding. Binda again played his man well, persuading Coppi to postpone his departure for a few days, knowing that the next day's stage was relatively easy, the day after that was a rest day, and that in turn was followed by a time trial which "he, the king of racing against the watch, was capable of winning on one leg."

With hindsight, the campionissimo acknowledged that his behaviour was not rational. To his critics, he said, "you try, just once, sitting on the roadside with an unusable bike, with the impression of being terribly alone, and with the knowledge that your rivals are all against you." Coppi told team-mates that in his view Binda and Bartali were in league and the reason his bike was not on the van was because Binda wanted Bartali to win. There was another explanation: Coppi had trouble adapting to the Tour. This was not the schematised, controlled racing of Italy where the gregari looked after things until the campioni took over. "Coppi's morale fell to bits because he realised that the Tour wasn't like the Giro," says Raphael Geminiani, a friend and rival, later a team mate. "Controlling the Tour was much harder, because everyone went from the gun, everyone was a danger, breaks could get a huge amount of time; it was more chaotic." There was Coppi's innate need for reassurance, the background of potential double dealing involving Bartali, and the sudden transition from dominance - 10 minutes ahead of the great rival on the road, a massive statement being made - to complete powerlessness.

St Malo marked a turning point: beforehand, Coppi had won only finished first in one major road race outside Italy, the previous year's Het Volk Classic, where the judges disqualified him for being given a wheel by a fellow competitor - another example of the difficulty of racing abroad. The dominant victories that followed, in the next couple of weeks and the next five years, suggested that getting back into the 1949 Tour actually made him a more formidable competitor.

* Coppi ate into that 37-minute lead for the next fortnight, eventually taking the yellow jersey in the Alps, after more conflict and intrigue with Bartali. In Paris he became the first cyclist to achieve a feat that few thought possible: winning the Giro and Tour in the same year.

"Fallen Angel: The Passion of Fausto Coppi" is available from Amazon.com UK for £16.99 and Amazon.com USA.