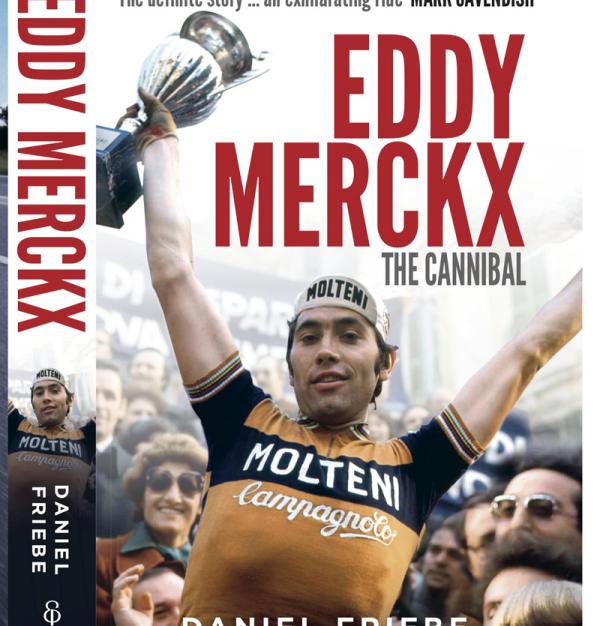

Extract: Eddy Merckx The Cannibal

Exclusive extract from Daniel Friebe's book

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Forty-five years ago this week, in the spring of 1967, Eddy Merckx was already a two-time Milan-San Remo winner, already a flat-track bully of some repute, but also just one of several would-be kings of the cycling world. Merckx’s second Tour of Flanders that year ended in a defeat which would prolong the illusion, or rather delusion, that Merckx was no different from prodigies who had come before, shooting stars who eventually waned with the hype which had accompanied their rise. The race also ended in victory for the garrulous Italian Dino Zandegù – and one of the more unconventional victory celebrations in a “Ronde”.

‘O sole mio

sta ‘nfronte a te!

‘O sole, ‘o sole mio,

sta ‘nfronte a te!

It’s my own sun

that’s upon your face!

The sun, my own sun,

It’s upon your face!

Dino Zandegù says the urge to sing came spontaneously, the words just flowed. Well, not exactly: a large and vocal group of Italian migrants stationed close to the prize podium had watched him cross the line, his right arm thrust towards the angry skies, his face and hands black as theirs after a day in the mines of Charleroi and Marcinelle, and broken into their own chorus.

First an ironic, ‘O sole mio!’, then an invocation to join them: ‘Canta, Dino, canta!’: ‘Sing, Dino, sing!’ And so Dino had sung, to the delight of his countrymen and the tickled disbelief of cameramen and journalists from all over Europe.

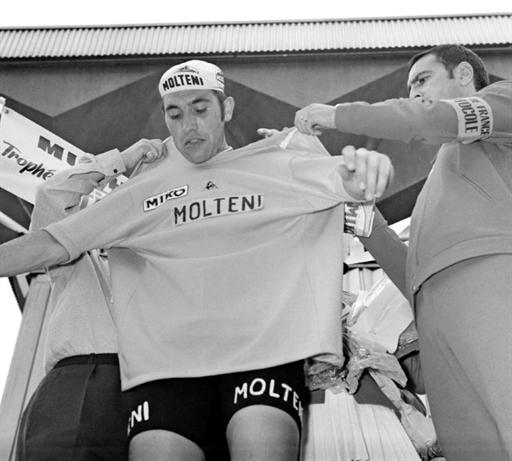

A few paces away, making his way through the mêlée, Zandegù’s Salvarani teammate Felice Gimondi also smirked. He had watched ‘Il Dinosauro’ win from 200 metres back down the finishing straight in Gent. Thirteen seconds later, Gimondi had followed Eddy Merckx across the line. As the blubs flashed and Merckx lunged, Gimondi harked the anguished cry of a beaten man.

If Zandegù’s performance on the cobbled hills, the bergs of the Tour of Flanders on the second day of April was a revelation, his singing was not, at least not for the Italian public. Ever since his Giro d’Italia début three years earlier, the baker’s son from Padova had enlivened many an uneventful race with his impromptu balladry, often accompanying an impressive baritone with exuberant arm-waving. If a birthday needed celebrating, all eyes would be on Zandegù in the middle of the peloton: his mouth and an eyebrow would rise mischievously at one side, he might disappear for a minute or twenty, then reappear balancing a birthday cake in the palm of his right hand and conducting the chorus with his left. ‘Buon compleanno a te! Happy birthday to you...’

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

‘Typical’, says Zandegù today: those three or four bars of ‘O sole mio!’ became more famous than the victory they were meant to celebrate. More famous even than him beating Eddy Merckx on the Belgian’s own patch.

It was to be the story of Zandegù’s career. No, of his life. He was a talented cyclist but a better showman. And an utterly brilliant raconteur. These attributes now earn him an annual invitation to the Giro d’Italia from state broadcaster RAI. In their daily, pre-stage eyesore exhibiting all the naffness that makes Italian television a national embarrassment, Zandegù is the performing seal in a circus commanded by the mustachioed ringmaster Marino Bartoletti. In 45 years, not much has changed; what Zandegù used to do within the bosom of the peloton, he now accomplishes in a makeshift studio in the Giro’s hospitality village. At Bartoletti’s unctuous behest, Dino sings, Dino dances, Dino jokes, Dino laughs.

Above all, Dino tells stories. On air and off it – to him it’s the same. No sooner have the credits rolled than ‘Il Dinosauro’ is shuffling off, his fingers are clasped like five thick salamis around a new listener’s, and he’s away. His tales are breathless, hysterical, crescendo-ing monologues delivered through a north-east Italian accent as gravelly as the unpaved sterrato roads which are often their setting. What’s more, says Zandegù, ‘ninety-five per cent of them are true’. Unless, that is, it’s the afternoon. Then, by Dino’s own admission, ‘the percentage falls to ninety’.

Dino, Dino, tell us about growing up...

‘Well, we didn’t have a lot but at least we weren’t hungry because we owned a bakery. You just about scraped by. The first batch of bread that Dad used to bake at 6.30, we kept to one side just in case the oven broke and we were left with nothing. There were 18 of us in the family: eight brothers, six sisters, Mum, Dad, Gran and Granddad. We all used to get together at four every afternoon to boil up the dry, stale bread, the pan biscotto, and put it into a kind of panzanella, a bread salad. It was buonissima! Better than what my wife makes now! Anyway, when I won races as an amateur, I’d come home, tell my mum and sisters, and my reward would be a cup of caffè latte and a corner of bread straight out of the oven. If I didn’t win, my mum pretended that she’d forgotten to cook and there was nothing you could do! Even my sisters were annoyed with me. Then if I got a bit friendly with a girl, they didn’t like that either! They’d tell me that I had to go and explain to her that I had to race my bike and mustn’t have any distractions. Thanks to them, I was practically a virgin at 26!’

Practically? Eh? Never mind...What about that Tour of Flanders in 1967? Beating Merckx, that must have been something...

‘Ah, yes, well my teammate Gimondi and I attacked with Merckx and came across to Barry Hoban, Noel Foré and Willy Monty, who had been in the break earlier on. After the Mur de Grammont climb, I attacked with Foré and Merckx was stuck, because Gimondi wasn’t going to help him. Foré was too tired after his earlier break to pose any threat in the sprint. I won easily. Then Merckx came over like this big, roaring lion, absolutely furious. I didn’t pay him too much attention. The Italian fans were shouting to me to sing, and it just came naturally. “O sole mio...!”.’

Dino, Dino, seriously now, should you all have known in 1967? Should you, could you not have seen what was coming?

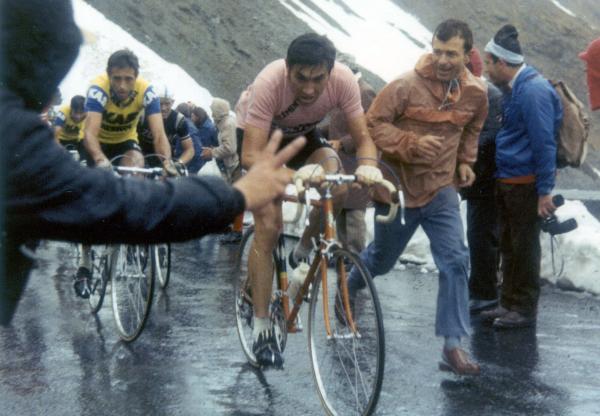

‘We were all intimidated. We were. This kid just arrived, this big, handsome Belgian kid with high cheekbones – the face of an immense athlete – and pretty quickly we all realised that on the bike he was a brute. […] He used to drive me nuts. When he was racing, you knew that he could put you out of the time limit any time. It was a constant, breathless chase. You’d see Merckx’s team on the front ready to make the race 150 kilometres from the finish, Van Den Bossche, Van Den this, Van Ben that – they all surged to the front – and he’d be pawing the ground like this big tiger. He couldn’t wait for the moment, kilometre X, when he would attack and smash us all to pieces. I used to tell him to go stuff himself. When you’re hurting, you turn nasty. I’d be shouting from the back of the bunch, “Vaffanculo, Merckx! Bastardo!” Half of the peloton detested him despite thinking that he was an OK bloke […] I say we all realised quickly but it wasn’t straight away. It took a while, a couple of years. We, we didn’t know, we didn’t...’

For once even Dino Zandegù is lost for words.

Eddy Merckx The Cannibal is available online at Amazon.