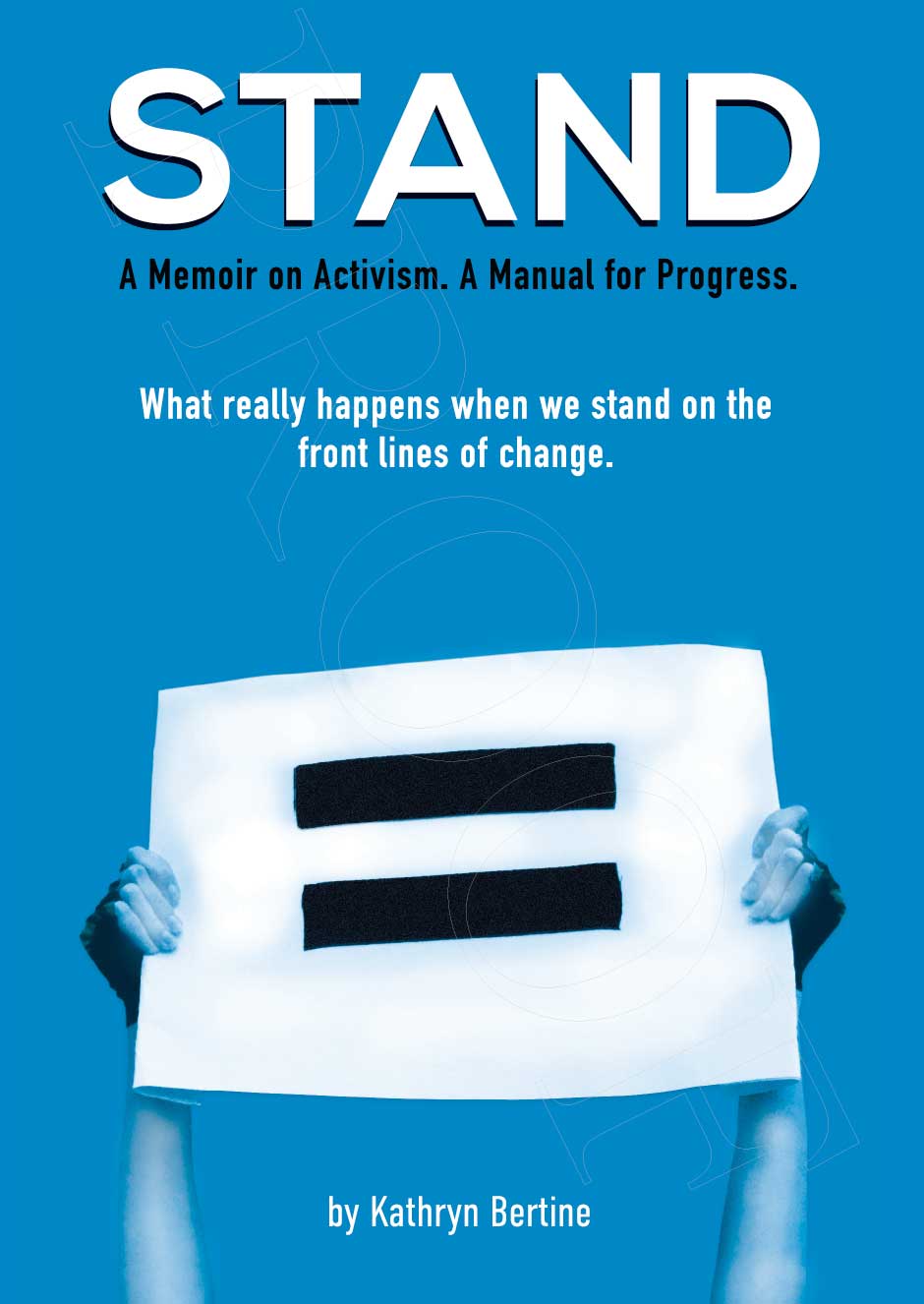

Excerpt: Kathryn Bertine's STAND

STAND: A memoir on activism. A manual for progress. What really happens when we stand on the front lines of change is out now

Kathryn Bertine's STAND: A memoir on activism. A manual for progress. What really happens when we stand on the front lines of change is out now. The book blends memoir, manual and manifesto into an intimate journey of advocacy, unmasking what really happens when women/minorities stand up and fight for change, including her journey through bullying, abandonment, depression, and a near-fatal crash. Reprinted with permission.

On a warm spring Arizona afternoon in 2009, I sat at my ancient desktop computer, with my index finger hovering over the send button. Then, paused. Hesitated. Waited. The weary fan in the hard drive wheezed and whirred with fatigue, in then out, one yogic cycle of mechanical breath. I eagerly wanted this email to fly through the data cables between Tucson and Paris, marking my first attempt to lobby the Tour de France for the equal inclusion of women. Still, I paused with my finger hovering over the button.

A whiff of the pungent scent of fresh paint hung in the air, as the deep red pigment labeled Scarlet Dragon exhaled its drying breath from the wall behind my desk. A wall I painted yesterday for no other reason than simply because I could. Such were the joys of first-time home ownership. The ties of an apron dug into my waist. I was a 34-year-old lunch waitress and my shift was about to start. Best to send the email now, I rationalized, since after the lunch shift I went directly to my second job as an adjunct professor of journalism at Pima Community College. Early mornings were spent cycling, middays spent working, evenings spent job searching. And researching women, history, sports and equal opportunity. I had worked on the contents of this email to Christian Prudhomme, race director of the Tour de France, for months. It was time. Send, I whispered. Now.

Every fiber of my being believed in this mission for gender equity. I didn't understand the wait—and weight—of the pause. Not then. I do, now. A decade later.

Something deep inside my soul grabbed onto that pause and held tight. Telling my gut, mind and heart that—should my finger press send—things would be different. Oh please, it's just an email. Enough. I brought my finger down upon send with gusto.

Hitting send was the moment my life in activism began, even though I didn't know it at the time. What I did know for certain was this: I wanted to be a professional cyclist. Because of a strange and wonderful turn I'd taken in my early thirties. After spending my twenties striving to be a professional figure skater then professional triathlete, my obstinate determinism had somehow caught the eyes of ESPN. From 2006 to 2008, ESPN hired me as a columnist/gonzo journalist/author as I attempted to qualify for the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics.

The catch? Not in figure skating. Or triathlon. It had to be any other summer sport. After six months of trying just about every sport on the planet, road cycling became my chosen path for the remaining eighteen months of the assignment.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

What started out as ESPN's idea of a "set-up-to-fail" foray into investigative journalism then blossomed into something else: a life-changing personal quest. From 31 to 33, my life as an athlete and a writer merged into one as my public and private lives strove toward the same finish line; an improbable Olympic dream. Hinging delicately on the border of sanity, I dove into this two-year assignment with equal parts personal and professional fervor. I wrote a book about the quest: As Good As Gold.

Spoiler alert: I did not qualify for the Beijing Olympics. But something wild happened. I almost did. The "almost" changed me. Sometimes, it is not the victories or losses that define our paths in life but the Wonder and What Ifs that lie between. When the ESPN assignment ended, my cycling did not. I was head over heels in love with this crazy sport.

I wanted to race bikes professionally. Not for ESPN, not for journalism. For myself. To fix some of this weirdly archaic stuff in the sport, like the fact only men could race the Tour de France. My love of road bike racing and equal rights for women took root. The ESPN assignment was over, but my passion was redirected. Game over morphed to game on.

During the 2008 Olympic qualification journey, I gained enough internal strength and power to rise to Category 1, the highest rank of amateur cycling. My position with ESPN literally afforded me the ability to try: all training and racing was covered during those two years. What wasn't automatically covered, however, was the key ingredient to athletic success: experience. To be strong and powerful is one thing. To know what to do with one's strength and power is an entirely different element. One that takes a lot of time. Making it to cycling's pro ranks wasn't going to be any easier than trying to get to the Olympics. The United States had about five top-tier pro women's teams where athletes received salaries and landing a contract was preciously rare.

The physical goal of being a pro bike racer was half my motivation. The other half stemmed from that same internal spring that fueled my inner journalist; exposing truths and solving problems. After nearly two years competing on the Olympic circuit of elite bicycle racing, I saw so many things that didn't make sense in our modern world.

Why were women's bike races shorter than the men's? Why fewer opportunities for women to race? Why were the smaller, poorer nations unable to enter or host races? Why do the women have fewer qualifying spots at the Olympics than the men? Why were the men of pro cycling earning thousands of dollars in prize money and the pro women just a few hundred? At the world's biggest, most famous bike race—The Tour de France—why is there no women's race? Those were my biggest Whys. But from 2006-2008 those Whys remained in the periphery of my own ESPN/Olympic quest. Now that the assignment was over, the Whys bubbled forth. Loudly. Requesting answers that I did not have. (Journalists hate not finding answers. Especially when there aren't any good ones.) On the heels of Why came my old friend, What If.

What if we could make this sport equal? None of this was really about racing bicycles. It was about challenging—and changing—any system where equal opportunity isn't present. Cycling was the medium, not the mission. Had I not qualified for the Knitting World Championships because women from St. Kitts and Nevis weren't granted access to the Yarn Making Preliminaries then I would fight just as hard for knitting equity. But it was cycling that grabbed my soul and didn't let go.

Perhaps, I thought, if I can become a pro cyclist and use my voice as a journalist, then we can truly create change in this weirdly archaic sport. And world. A new quest began.

A few months before sending the email to Christian Prudhomme in France, I began 2009 by ignoring the pit in my stomach slowly being gnawed away by reality. My dreams of becoming a pro cyclist were great, but food, shelter and bills took precedence. When my Olympic quest ended, I held hope my columnist position at ESPN would continue. There were promises of a new assignment. My two-year column So You Wanna Be an Olympian? had over two million hits per installment, which is none too shabby for a female amateur athlete writing for the male-dominated audience of professional sports on ESPN. Editors, executives and I engaged in discussions and promises of my next role with ESPN. I put three ideas on the table: A documentary installment profiling the amazing athletes of lesser-known sports. A column about the growth of sports/athletes in underdeveloped nations. And—my personal passion—a column on what exactly it would take for women to race the Tour de France.

See, I explained, all three of these ideas came from the experiences I encountered during As Good As Gold, so it's a natural connection to the original subject, and all the ESPN readers keep asking what's next, so hell, we could cover all three topics over the next few yea—

"Kathryn," ESPN said. "The economy's bad. We're on a hiring freeze."

"Right," my optimism answered. "But that'll thaw soon!"

Unfortunately, my optimism was not in charge at ESPN. They did not renew my contract.

The U.S. economic crash of 2008, as we know, did not thaw soon. Unemployment soared to 10 percent in 2009, nearly double the pre-recession percentage. In addition to my own unemployment, my nerves kicked into full gear when my humble, little condo—a non-luxurious, rectangularly cozy, 800 square-foot palace of independence knighting me into adulthood upon purchase—was suddenly slashed to half its value. I quickly evaluated my prospects. As Good As Gold would not be published until 2010. Living off royalties wasn't a reality. Unless Steven Spielberg bought the rights. I treasured this fantasy. The improbable odds of Steven Spielberg buying my life story actually made the odds of becoming a pro cyclist in my thirties seem much more attainable. Until then, reality harkened. To train, race and travel toward the goal of securing a pro contract, I'd need to do what most athletes do: work several other jobs while rising through the ranks.

I found a "new" 1999 Volvo station wagon with 150K miles for $4999 and purchased it with a credit card. I felt exceedingly affluent driving a car with little plastic windshield wipers on the headlights. One of them even worked. I took a job waitressing and landed an adjunct teaching position at Pima Community College. Combined, those careers brought in about $1000/month. Which happened to be the same price of my mortgage. I took in a roommate to cut that expense in half. Then I picked up a $250/month sponsorship from a local benefactor who sponsored athletes. The budget left about $50 a week to spend on groceries. I already mastered the art of discount shopping at Grocery Outlet during my grad student days. God, I loved that place. There were fruit flies in the produce section and boxes of Christmas-themed Rice Krispies in July and weirdly exhilarating foreign foods with pretty pictures that I devoured without actually knowing what they were.

Ok, I could do this again. After all, it was just a hiring freeze at ESPN. I believed everything would be fine. I also believed in unicorns. Going from a livable salary with ESPN to an annual income of $15,000 was terrifying.

"At least you won't have to pay taxes since you're below the poverty line!" my internal optimist chirped. She's annoying as hell. Some days I want to punch her in the face. Lucky for her she was also correct. The poverty line in 2009 hovered at $17,500.

As 2009 rolled underway and I settled into waitressing and adjunct-ing, I sought out all pro cycling prospects. I applied to every professional team, citing the results of my 2008 races during my ESPN quest. As I naively bumbled my way through the Olympic qualification journey, I was fortunate to garner some decent UCI results. From Uruguay to China to Venezuela to El Salvador, in the midst of my fledgling rise through the ranks, I somehow garnered a few top twenty finishes in fields stacked with Olympians and national champions. Locally, I was the Arizona state champion. Also, the national champion of St. Kitts and Nevis, which I vowed to represent for the remainder of my cycling career.

Surely, I thought, these were enough accolades to get noticed by the professional teams. Perhaps I wouldn't be the team leader, but the role of domestique—the French term for "servant" aka workhorse—was the role I wanted. Neither a sprinter nor a climber, the steady grind of endurance was my physiological diesel engine. Taking long pulls at the front of the peloton, fetching bottles, attacking, chasing, blocking the wind… these were my skills. At 34, my mental and physical stamina were stronger than ever. With a background in print and web media, I could also offer teams something off the bike, too: journalism exposure. Perhaps these might be considered a bonus! Confidently, I sent my race resume out to every pro cycling team in the U.S., Canada and Europe. There had to be one team would consider a workhorse with experience and media perks.

Nope. Not one. I received nine rejections. Half of which were outright Nos, half of which were ghosted silence. No professional team wanted anything to do with me. Where I saw my enthusiasm, confidence, experience and results as pluses, the reality of pro cycling saw the minuses: Top-twenty results aren't wins. My race experience was less than two years. Worse, my experience as a human being was greater than 28 years. I thought 34 was a good thing until a fellow pro cyclist I admired, Alisha Welsh, explained otherwise.

"The UCI has a rule," Alisha explained, "that women's professional teams must have a median age under 28 years old."

"What?! That's insane!" I balked. "Kristin Armstrong just won her second Olympic gold medal in time trial cycling at 39!" This archaic rule made no sense. "Why is this rule still around?"

Alisha shook her head. No idea. I did a little digging. As if the UCI couldn't be any more backward in their antediluvian rules stating women must race shorter distances, earn less prize money and receive no base salary, UCI hit the quadfecta of outdated idiocy. Indeed, there it was: All UCI women's pro teams had to average less than 28 years of age. This rule was established not in 1909 but 2009… when the UCI merged men's and women's pro teams into the same chapter of UCI regulations. What sounded like progress—treating the men's and women's pro teams the same—came with a subtle loophole of inequity.

In 2009, there were two levels of pro ranks for the men: Pro Continental and World Tour. Minor league and major league, respectively, as exist in most men's professional sports. The UCI minor league men had an age median, the major league did not. Where women got screwed was the fact there was no major and minor league system. Just one professional league with an age median placed in effect for every women's pro team. Worse still, was the idiocy of an age median at all, men or women. But especially women: physiologists discovered women in endurance sports hit their peak in their mid-30s to early 40s, finally helping erase the errant history where, in 1966, doctors actually believed ovaries would fall out if women exercised. The rule for women's pro cycling teams being below age 28 made absolutely no sense. But there it stood, smackdab in the middle of the UCI rulebook. Archaic, uniformed and unchallenged.

Puzzled by the UCI's ignorance of modern data, I sifted through the rosters of the top-tiered women's pro teams. Sure enough, the majority of athletes were younger than 28 because of this rule. But not all of them. Some were older than me, and thriving. There was seven-time U.S. national champion Dotsie Bausch on Team Tibco, six-time U.S. national champ Tina Pic on Colavita Pro Cycling, two-time Olympian Ina Teutenberg of Germany on Team T-Mobile … all of whom were in their mid-to-late thirties. I spent the past two years idolizing these badass pro cyclists not for their age but for their incredible performances. Bausch, Pic and Teutenberg were the Gretzkys, Jordans and Favres of women's pro cycling in the mid-2000s, all of them older than the ridiculous age median and still kicking ass.

Despite my two functioning ovaries still hangin' where they're supposed to, my chances of signing a pro contract in my mid-30s wasn't looking good. I had a choice: view the age rule as odds stacked against me, or to see the presence of Bausch, Pic and Teutenberg as the possibility of opportunity. I chose the latter and kept applying to pro teams.

While my pro team hopes fizzled for the 2009 season, I sought out amateur teams who raced events where pro teams also competed. A bicycle shop in Phoenix partnered with Specialized Bicycles and created an elite domestic team in Arizona: Specialized-Bicycle House, which offered me a spot. There would be no salary and no free bicycle. I'd need to pay my way to just about every race. I would receive two free kits (cycling outfits) and a couple water-bottles. Maybe even a paid race entry here and there.

As I teetered on the cliff of financial struggle, free water bottles and clothing felt like gold and platinum. I took the offer and deposited it in the Bank of Progress. Now I could hopefully work my way up the ranks. Maybe catch the eye of a pro team for 2010. These were the dues every athlete pays in any sport: Show up. Do well. People notice. Move up. I joined Specialized-Bicycle House with my closest Tucson friend, Marilyn Chychota. Unlike professional teams where athletes are given bikes for the year, most elite teams lend out loaner bikes. This team did not. If we wanted to ride a Specialized bicycle, we had to buy one. Neither Marilyn nor I were able to afford a new bike so we rode the old bikes of our previous sponsors, Wilier and Trek, respectively. To race on a Trek and wear a Specialized jersey was the equivalent to showing up in a Chevrolet to a Ford event. Still, we had free clothing and energy gels, so we held our heads high and happily deflected the quizzical looks and questions from our competitors.

"Why doesn't your bike match your sponsor?" they'd ask.

"We're just happy our shorts match our shirts," we'd smile.