Evgeni Berzin: Russian Roulette

A look back at the 1994 Giro d'Italia and the fallout with Gewiss

This feature first appeared in Procycling magazine. To subscribe, click here.

The 1994 Giro d’Italia saw the emergence of a truly brilliant stage racer, Evgeni Berzin, but the Russian followed up his pink jersey by falling out with his team and never hitting those heights again. Procycling asks where it all went wrong.

Growing up close to the Finnish border in Vyborg, Evgeni Berzin hadn’t needed to look far for a cycling role model. Viatcheslav Ekimov, four years his senior, had been a world and Olympic pursuit champion for the Soviet Union and then, when the Berlin Wall fell, he became a top professional in the west.

Berzin had been dispatched to a Leningrad sports school at 14. Placed in the ‘care’ of a despotic old-school coach named Alexandre Kuznetsov, he won multiple world titles on the track. Like Ekimov he was a pursuiter par excellence but just like Ekimov he dreamed of riding the great stage races of Italy and France.

He set his sights on the road race at the 1992 Olympics, the biggest shop window of all. Kuznetzov, though, was having none of it. He had no time for Berzin’s naked ambition, much less for his professional aspirations. His job, he informed him, was to do precisely as he was told, keep his mouth firmly shut, and to deliver Mother Russia the track gold for which he was paid.

For seven years Berzin had been obliged to submit to his will but now, with travel restrictions lifted, he was at liberty to come and go as he saw fit. He told Kuznetzov to take a running jump and booked a flight to Italy for himself and Stella, his girlfriend. It was January 1992 and his very future was on the line.

Berzin made directly for Stradella, an hour or so south of Milan, to meet Emanuele Bombini. Recently retired, Bombini had been a faithful gregario for the likes of Gianni Bugno and Moreno Argentin. For now he was managing an amateur team but he had an exciting new project under way.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

He’d reached agreement with Aurelio Messina, a cycling fan whose Mecair engineering company sponsored a local amateur team. Messina was a big fan of Argentin, the Classics champion, and wanted a professional team of his own. Bombini told him he could build him a very good one around his great idol. Like most Russians, Berzin was low on cost and high on ability, and Bombini told him he wanted him on board. He’d sort out a house for him and Stella in nearby Broni, and to ease his passage he’d also find a place for his best friend. Vladislav Bobrik, too, was a gifted rider and his ship, like that of Berzin, had just come in. They sorted out the paperwork and Evgeni Berzin waved goodbye to the track, to Russia and to Kuznetsov.

The 1992 season went well. Berzin won big amateur races in Poland and Brittany (among others), and Bombini was as good as his word. The house in Broni was nice, the people friendly, the food and climate ideal. Stella, Evgeni and Vladislav integrated well, and Evgeni in particular was well liked around town. He was blonde-haired, blue-eyed and outgoing, and he learned the language quickly and enthusiastically. All that, allied to his cycling exploits, made him something of a local celebrity.

He and Bobrik signed on when Mecair-Ballan was born in January 1993, and they were joined by another former Soviet, a veteran Lithuanian stage racer named Piotr Ugrumov. At the Giro, Argentin won the opening stage and wore pink for nine days. Better still, Ugrumov, 20th the previous year, came within 58 seconds of defeating the great Miguel Indurain on GC. Ugrumov was 32 now, and in seven previous Grand Tours his best result had been eighth. Under the alchemist Bombini, however, he rode a sensational three weeks. He consistently outclimbed the best in the world while Berzin, fetching and carrying as he was bid, got round in 90th place.

Argentin had formed a close relationship with a charismatic sports doctor, and was enjoying a remarkable Indian summer. Michele Ferrari had been an acolyte of Francesco Conconi, the sports scientist who had revolutionised cycling preparation. Conconi had revived the careers of luminaries such as Maurizio Fondriest and Francesco Moser, and Argentin thrived under the sorcerer’s apprentice.

Ferrari and Conconi were transforming cycling. Walter Polini, himself a former professional, had been the team’s medic but on 1 July he stated that he wanted nothing more to do with a sport he’d been around all his life. He said the whole thing was ‘filthy’ and so Ferrari, his star firmly in the ascendency, was added to the payroll. Two weeks later Alberto Volpi, another of his disciples, won the Leeds Classic for Mecair. On 25 July, however, the results came back from the lab. Volpi had been positive for growth hormone. The first cracks in fortress Bombini.

Whatever; by the season’s end Berzin had finished second in a stage of the Tour of Britain and was improving by the week. He’d impressed Bombini with his courage, contributed unstintingly at the Giro and, like most of the former Soviets, finished every race he’d started. He was officially the 379th best cyclist in the world. He’d made a good start.

The Gewiss electronics company had offices in Broni and they replaced Mecair as title sponsors in 1994. Berzin’s form was stunning from the get-go and by the end of February he’d got top threes at the Tour of the Med, Laigueglia and Sicily week. New signing Giorgio Furlan won the Trofeo Pantalica and then dominated Tirreno. He won three stages and the overall, with runner-up Berzin sparkling throughout. At Sanremo, Berzin’s forcing scattered the peloton to the four winds, before Furlan rode away on the Poggio. On a 53x14 gear. Quite incredible.

On 27 March Berzin won the time trial of the Critérium International. A supercharged Furlan would win the GC, with Berzin and Tony Rominger also on the podium. Rominger, too, was a high-profile client of Ferrari and by now it was clear that a select group of riders – his riders – were winning pretty much every time they pinned on a number.

The Dutchman Edwig Van Hooydonck was first to break ranks. A double Tour of Flanders winner aged just 27, he was being thumped by guys he’d ridden away from in previous years. They were turning huge gears and riding at speeds he couldn’t hope to match. He publicly accused “the Italians” of cheating, eliciting a sharp rebuke from UCI president Hein Verbruggen. On April fool’s day Verbruggen issued an open letter to the press, stating that the insinuations had no factual basis, that cycling had an exemplary anti-doping record, and that any continuation of the rumour-mongering would result in legal action. Five days later at Gent-Wevelgem, the speaker, only half-joking, asked Franco Ballerini to name the “magic potion” of Italian cycling. “Professionalism,” replied Ballerini. “And hard work.”

Berzin finished second again at the Tour of the Basque Country, defeated once more by Rominger. Three days later, on 11 April, he and Bombini shook hands on an improved contract, tying him to Gewiss until 1996. Then he flew to the Ardennes.

On 17 April 1994, Evgeni Berzin joined a six-man break on the road to Liège. The likes of Rominger and world champion Lance Armstrong watched on helplessly as he soloed to a breathtaking win. Afterwards, big-mouth Ferrari, his ego in overdrive, left the world’s cycling press speechless; “Is EPO damaging? I’m not aware of anyone having died from using it. Like all things it’s about balance, quantity. I don’t prescribe it to my riders but I can justify their using it. If I were a cyclist I’d use substances that aren’t detectable in anti-doping if they improved my performance and enabled me to be competitive. If it’s traceable it’s doping, and if it isn’t it isn’t.”

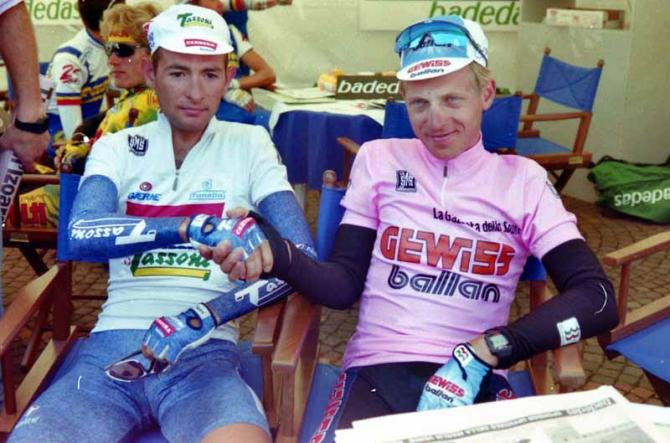

Three days later Gewiss produced one of the most infamous displays in cycling history. The Argentin-Furlan-Berzin 1-2-3 at Flèche Wallonne was itself extraordinary but so too was the composition of the top 10. All bar one rode for Italian teams and all bar Berzin and Frenchman Ronan Pensec were Italian. More astounding still, Michele Ferrari, the doctor of the Gewiss cycling team, saw fit to convene a press conference independently of his employers. He told an incredulous audience that “anything that doesn’t result in a positive test isn’t doping”, prompting L’Équipe to headline, “Gewiss are driving a Ferrari”.

Ferrari was an outstanding preparatore but his arrogance and hubris had made him a PR liability. Gewiss were left with no choice and fired him, but Berzin refused either to denounce him or to desist from working with him. Gewiss were powerless to stop Ferrari ‘advising’ him, just as they were powerless to stop the others.

Five days on from Flèche, Berzin romped home at the Tour of the Apennines. Now, hypnotised by the freak show unfolding before their very eyes, the press began making facile comparisons with Jacques Anquetil: same resting heart rate, same dreamy pedal-stroke, same blonde hair and blue eyes. Suddenly Berzin, 379th in the world just four months prior, was held aloft as the future of the sport.

On 11 May Moreno Argentin won stage 2 of the Tour of Trentino, and with it the leader’s jersey. The following day, however, Berzin launched an attack. He was reined in but it led to an evening meeting at the hotel. Bombini clarified their roles and, as Argentin won the GC, the Gewiss benefit rolled on.

Only Berzin, the man who would be king, was increasingly fractious and increasingly detached. Rumours were circulating that Stella, the tsarina, was far from happy. She wanted out of little Broni, they were saying, and into Monte Carlo. The contract her husband had signed, estimated at 50 million lire (about £17,000) before tax, in no way reflected his worth, an insult to their intelligence. Five days before the Giro, in advance of the Tour of Friuli, Berzin told Bombini he needed to renegotiate. He was informed that the contract had already been deposited with the federation and that it was legally binding. Berzin (and by all accounts Stella) was livid.

For all that he seemed intent on isolating himself from his colleagues, his form on the bike was imperious. Thus he began the Giro as co-leader with Ugrumov, with venerable old Argentin cast as road captain. Furlan would hunt for stages, while Bjarne Riis would share gregario duties with Volpi, Enrico Zaina and Bruno Cenghialta. Berzin crowed that he could beat Indurain in the opening day time trial at Bologna and, at Ferrari’s behest, insisted on a special low-pro bike. Beat Miguel he did, though ultimately the French specialist Armand De Las Cuevas snatched the jersey. No matter; in one afternoon, Berzin had unsettled Indurain and thumped Ugrumov out of sight.

The Giro was to be Argentin’s final race as a professional, a last hurrah for a great champion. He celebrated by winning stage 2, and with it the maglia rosa. Argentin wasn’t deluding himself he could win the Giro and so Berzin was given leave to attack on stage 4 to Campitello Matese. He caught the lone breakaway, a popular gregario named Oscar Pelliccioli, and plundered both stage and pink jersey. In so doing he put a minute into Indurain and three more into the hapless Ugrumov. It appeared to be another great day for Gewiss but there was a flip side.

Most agreed Berzin had been out of order in denying Pellicioli his first professional win. Both protocol and common decency demanded he gift him the stage and content himself with the race leadership. Berzin was a great rider, no question, but within Gewiss the feeling was that he was just too big for his boots. By the time he annihilated Indurain (and everyone else) in the TT at Folonica, he was treating his gregari, among them the great Argentin, with something approaching contempt. They demanded a meeting with Bombini and told him they were doing their utmost. They were the strongest team in the race but Berzin was constantly chiding them for their shortcomings. Worse still, he was telling anyone who’d listen that he wanted out of Gewiss, effectively using the Giro as a shop window. He was winning the great race but he wasn’t showing it – or indeed his team – anything like due deference.

Marco Pantani, a new climber from Cesenatico, danced away from him on the Stelvio. He did so again on the stage to Les Deux Alpes but gregario di lusso Argentin buried himself in his service. It was the one and only time Berzin looked even remotely vulnerable and little wonder. Indurain, the number-crunchers informed us, was capable of 550W (for 20 minutes) to his 510, but the Spaniard was 7kg heavier. Complicated or otherwise, the winner of the 1994 Giro was one freakishly talented bike rider.

Gewiss said they’d renegotiate in light of the Giro win but Berzin refused the olive branch outright. He engaged Michele Ferrari’s lawyer and told Bombini that, come what may, he wouldn’t be riding for him again. Polti wanted him to replace the ageing Gianni Bugno and he’d been advised that his contract wasn’t binding in law. Gewiss, their patience exhausted, fired back that if he didn’t ride for them in 1995 he wouldn’t be riding at all. In August he shambled round at the World TT Championship, a dismal 21st. It was his second day’s racing since the Giro, and it would be his last of the season. Bobrik moved out, saying he wanted nothing more to do with him, and then won Lombardy for Gewiss. Two days later, Berzin, in receipt of an offer from Polti, lodged an act with the federation. He’d stop at nothing to extricate himself from Gewiss. With Polti apparently prepared to make a millionaire of him, the stakes couldn’t have been higher.

With the lawyers’ daggers drawn, the public slanging match continued through the autumn but on 1 December Evgeni Berzin’s world collapsed. The court found in favour of Gewiss, Polti politely withdrew their offer, and Stella was condemned to two more years in Broni.

Evgeni Berzin, the enfant terrible of cycling, had played Russian Roulette with his future and lost.