Eusebio Unzué: In it for the long haul

Movistar manager has been at the cycling game for more than 40 years

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The first thing that strikes you about Eusebio Unzué is his sheer longevity. He's been the manager of the team ranked the best in the world for the last three years, and he managed Miguel Indurain for his entire career, but his greatest achievement is the length of time, over 40 years, that the Movistar manager has been doing his job. During that period, Unzué's directing experience has ranged from working with juniors in the embryonic Reynolds squad in the northern Spanish region of Navarre to guiding Spain's greatest ever athlete, Indurain, to multiple victories in the Tour de France. In the process, Unzué, born into a family of agricultural seed merchants in the town of Orcoyen in Navarre, and with no family roots in the sport whatsoever, has himself become both cornerstone and father figure for Spanish cycling, with his team, Movistar, so long-lasting it is a national institution.

Most of Spain's stage racing stars since the early 1980s have come within Unzué's influence at some point, although there is one notable exception. Double Tour winner Alberto Contador was never in Unzué's team. Carlos Sastre, the 2008 yellow jersey, never raced for Unzué as a professional, but even he cut his cycling teeth in Banesto's amateur squad.

The current incarnation of Unzué's team is Movistar, which took over sponsorship from Caisse d'Epargne in 2011, but the team's roots go back to the early 1970s. The Irurzungo-Alay team, named after the tiny town of Irurzun in southern Navarre, came into existence in 1970 and initially, Unzué was one of their riders. But aged 18, he sold his bike - a Marotias, one of the best available in Spain at the time - for 30,000 pesetas (500 euros), and spent the money on a second-hand Seat 124, which was pressed into service as a team car. The transaction was symbolic of Unzué's move from rider to manager of the team, which by this point had a dozen or so riders. It was also a risky move, characteristic of Unzué. "For many years, the team was more like an adventure than aiming at a particular goal," he said. But Unzué combined that willingness to take risks with a flair for securing commercial backers, and in 1974 he pulled in Reynolds, an aluminium-making multinational which had a factory in Irurzun.

That initial backing from Reynolds amounted to a comparatively paltry 100,000 pesetas (€1,500), but as their riders matured, Reynolds turned from a junior into an amateur team in 1978. That was when José Miguel Echavarri arrived, starting a partnership with Unzué which lasted three decades, and which shaped Spanish cycling for generations.

Few cycling managerial relationships have endured so long, nor been as productive and above all, united. Unzué described himself and Echavarri as "the accelerator and the brake pedals in the same team car."

"From the start, what enabled them to work so well together was how seriously they took bike racing," says David García, former Movistar PR officer and author of a history of the squad from its Reynolds days, Nuestro Ciclismo, Historia de un Equipo [Our Cycling, History of a Team]. "At the time, Spain had many squads that either never paid their riders, or paid them badly, and which were simply interested in winning riders, burning them out in the process. Reynolds was never like that. Unzué and Echavarri always believed that the image of a team, its stability, was as important as the results they obtain. And that was one of the secrets of their longevity."

In 1980 Reynolds moved up another level and created a professional team headed by Echavarri, and five years later Unzué officially quit running the Reynolds amateur team – although on an informal level, the relationship between the two squads was always very fluid, with staff, headquarters and team material all shared. This makes Unzué the joint longest-standing manager in ProContinental or WorldTour level cycling, equal with Belgian Hilaire Van Der Schueren, the current Wanty-Groupe Gobert manager, who also started in 1985.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

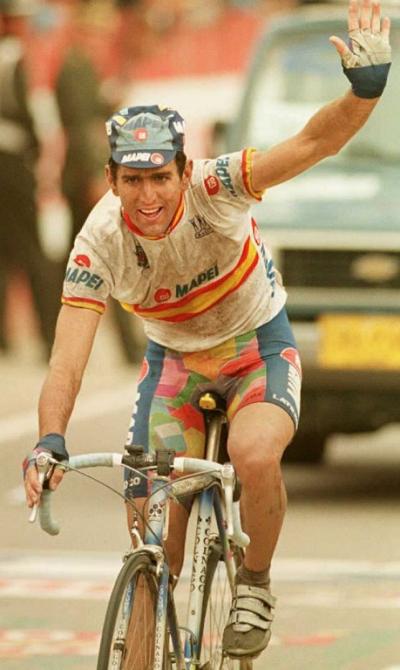

But whereas Van Der Schueren has worked mainly with smaller Classics-focussed squads, the Echavarri and Unzué tandem were to have a huge impact in the very biggest races. That process started with Ángel Arroyo and Pedro Delgado in the Vuelta and Tour de France in 1982 and 1983 and reached the highest of high points for a first time in 1988 when Reynolds and Delgado garnered a ground-breaking win for Spain in the Tour de France. Reynolds were replaced as headline sponsors by Banesto and the team took five further victories in the Tour along with two in the Giro d'Italia with Miguel Indurain in the 1990s, a period still considered as Spanish cycling's golden era. Unzué and Echavarri subsequently managed riders as important as Abraham Olano, Jose María Jiménez, Óscar Pereiro and Alejandro Valverde, who still races with Unzué at Movistar.

"I had an identical kind of relationship with both but they are very different people," Indurain said. Their roles were quite clearly defined, however. Although both Echavarri and Unzué were heavily involved in the day-to-day running of the squad, Echavarri was initially also the team ‘ambassador'. He was the one who dealt with the UCI, who negotiated with race organisers and sponsors, and who above all could deliver lengthy, almost poetic explanations of his team's strategies to the media.

A very clear idea of how the two worked so well together came in one of their very last joint interviews, in 2007 for the Spanish daily El País. Echavarri's analysis and opinions of their 30-year history occupy most of the article but each time the much punchier observations by Unzué kick in, they both act as a summary of what's been said and open up the next wave of Echavarri's recollections. What's notable, though, is the level of agreement between the two, the way the conversation bounces between one another so fluidly. It's as if it's one person talking but with two voices.

By the early 2000s, Echavarri was increasingly delegating his day-to-day team tasks to Unzué, although he was still a force to be reckoned with in the team. "José Miguel never seems to be there but when you least expect it, he pops up in the team hotel, like some kind of sorcerer," said rider José Iván Gutiérrez in 2007, the year Echavarri quit. Echavarri, seven years Unzué's senior, left Unzué to continue solo in his managerial career, first working with leaders like Valverde and then Nairo Quintana, with no small degree of success. In fact, 42 years after that life-changing decision to sell his Marotias bike, Unzué remains, aged 60, the hub of his team's management, and he's kept his team at the top of the WorldTour ranking, ahead of much-vaunted newcomers like Team Sky. So much for those who had written Unzué off as Echavarri's sidekick.

The million euro question about such a lengthy and prominent role in one of cycling's leading teams is what has prevented Unzué from suffering burn-out. "That hasn't happened because of the huge amount of passion he feels for the sport," García says. "It's hard to believe, particularly if you remember that he has won almost every race a director could dream of, and financially, he has no need to continue working. He could almost view his job as a hobby but he doesn't. He wouldn't be able to handle treating it like that. I can't see him ever retiring, either. He cares for the sport so much he wouldn't know what to do with his time."

Unzué is an affable but quietly-spoken type, and García says, "For those who don't know him, the way he talks, which sometimes seems insubstantial and roundabout, might make him seem a little bit uninvolved. But you couldn't be more wrong. When you hear him discuss the team with other members of staff, he couldn't be more fired up. He's always on the ball when it comes to riders and races, he likes to be in the loop on everything. That's got its virtues and its downsides, and it can mean things change too slowly sometimes. But at the same time, everybody has their own character, he's been here 35 years and it's very difficult to change that now."

On the plus side, Unzué's huge experience, combined with keeping such close tabs on the riders, has always had a hugely beneficial knock-on effect when it comes to Movistar producing the best line-ups possible for each race they do. As one insider puts it, "It might be a race as small as the Vuelta a Andalucía, say, but the amount of agonising, deliberation and collating and evaluating of all the possible information that Unzué puts into working out exactly which riders he wants to take part… You wouldn't believe it." As a result, unlike other top squads whose line-ups are chosen and the flights booked months in advance, Movistar riders often don't know until a few days before the race if they are taking part. That may drive up the cost of a few plane tickets but the result is that "often the riders Unzué will go for at the last minute are the ones who perform the best."

Linked to that is Unzué's life-long ability to read races. According to an interview in the Diario de Navarra newspaper with José Legarra, who directed Unzué as a rider, "When he was racing as a junior he had a sixth sense for getting in the right position. He raced cleverly but he didn't have the physical talent to match that, nor was he prepared to make the kinds of sacrifices that juniors needed to."

Legarra recalls Unzué dropping back to the team car to give him an overview of the race and the different riders. "Not a lot of 17-year-olds can do that kind of analysis," he says.

Unzué was equally gifted at understanding professional racing. Although he was often overshadowed by Echavarri's oratorical skills. It was Unzué who correctly forecast in the 1980s that "Miguel Indurain will win the Tour de France before he wins the Vuelta."

Equally, Unzué was sometimes slated for his and Echavarri's conservative tactics, particularly in the 1990s. But that strategy was exactly the one that a rider such as Indurain, a strong time triallist rarely given to launching attacks, needed to accumulate his seven Grand Tour wins.

It's possible that Unzué's collaboration with Echavarri contributed greatly to his longevity as a manager. As Unzué put it once before Echavarri's retirement, "I value more working together with José Miguel than I do putting together my own team, even though I feel more than capable of doing that."

Further back, until 1980 Unzué was joint team manager of the Reynolds amateur team with Legarra, too. It wasn't all about sharing the glory and pressure, however: Unzué and Echavarri took joint responsibility for what they called some of the team's biggest mistakes, such as the decision to end the Banesto amateur squad in 2002.

Unzué has never had the high media profile garnered by opinion-forming directors such as Echavarri, Dave Brailsford, Marc Madiot or Jonathan Vaughters. But few would question the star quality of the teams he has formed, with nearly 900 victories and counting in over 30 years of existence – roughly 30 a year. The team used to find most success in stage races but with Valverde they've also won Spring Classics.

Unzué's talent for gaining key, enduring sponsors has been partly responsible for the team's survival, in an era when Spanish cycling has been sinking fast collectively both in terms of squads and races, to the point where only Movistar remains in the UCI WorldTour.

"How many other squads have had so few sponsors – five – in three and a half decades?" asks García, rhetorically. That ability to garner solid financial backing dates right back to the Reynolds days. In 1980, their backing was 15 million pesetas. "If I'd given them any less, they'd have had to hitch-hike" was how Juan García Barberena, the Reynolds factory boss in Irurzun, put it with a certain degree of amusement. That figure went to 300 million pesetas in 1986. Even allowing for Spain's runaway inflation levels in the 1980s, that was a huge increase.

By 1989, Reynolds could no longer afford the team but Echavarri and Unzué convinced Spanish bank Banesto to take over for a further 15 years, until 2003, long after Indurain had hung up his wheels. Following the comparatively brief interlude of Illes Balears and Caisse d'Epargne, the timely arrival of Movistar, present from 2011 after a rumoured few helpful phone calls from Spain's Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, continues to guarantee stability for the team to the present day. Movistar's sponsorship in turn was, a team source says, partly helped by "Eusebio's good contacts with the highest spheres of Spain's establishment from his Banesto days. That was just as well, because after Caisse d'Epargne said they were quitting, sponsor-wise the team was in a very delicate position."

Finally, as Unzué admits, there has been a considerable slice of luck, in that the riders who appeared in the Unzué-Echavarri years, like Delgado, Indurain, Pereiro, Abraham Olano or Valverde, have been some of the most talented Spain has ever seen. It's worth remembering that Unzué and Echavarri may have put everything in place for such riders to flourish, yet without the riders' wins, their project would probably have been more short-lived.

Such longevity and such a run of success may have provided Spanish cycling with a reference point and a flagship team for nearly four decades, but inevitably, concern as to what will happen once Unzué retires is increasing. "When he does go, the gap he leaves behind will be almost impossible to fill," García says. "It's just like the squad: how likely is it that a team can grow from the tiniest of formations to become the best in the world and still be there after 35 years? That kind of continuity is almost impossible to imagine nowadays. He and his team – they are one of a kind."

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.