As our team works to develop an authority on what the best road bike is, we test all kinds of bikes. Like any buyer's guide, we try to have a range of products at different price points that fulfil different needs. That means while we test the kinds of bikes that most people buy, we also test bikes that most people would refer to as superbikes.

Among those that I have tested is the Enve Melee. It's a bike that I said made me feel young again and what I meant was that it was a fun bike. After that I tested the Cannondale Supersix Evo Hi-Mod, then the BMC Teammachine R, and to cap off 2023 I've been spending time on the latest Look 795 Blade RS. Each time I test one of these bikes, there's a distinct personality.

That distinct personality is at odds with the common perception that all bikes at that level are the same. The reality is that bikes are not all the same, no matter what the price point is, and I find that an interesting concept. A collection of carbon fibre race bikes at similar price points that feel so different feels almost impossible. I wondered where that came from and I set out to find an answer.

Given that their headquarters isn't far from me, I started with Enve. Even beyond the ease of doing a deep dive with the brand, the nature of the bike's personality had me the most curious. My experience of the bikes is that Cannondale is the efficiency king, the BMC is excellent at straight and fast, and the Look is a very stiff bike for those that like to climb. Of those personalities engineering an ephemeral feeling seems the most difficult and I was curious to hear how the brand accomplished it. Here's what I found.

It’s intentional

According to Enve, when you think about the feeling of the Melee, it comes from two different directions. The first piece is that it's simply an intentional choice. I spoke to Design Engineer, Kevin Nelson at length about what I thought about the bike and if that matched up with his intentions. Short answer, yes it does.

Nelson talked about how Enve looks at bike products as being on a continuum. One side is all about speed even if it's only a little bit and no matter what the cost. Leaning in this direction is why the BMC Teammachine R specs the DT Swiss ARC 1100 Wheelset. That wheelset is technically fast but with a narrow profile, those wheels give up a lot for that speed. On the other side of the continuum you might find yourself with a gravel bike. Comfort is your number one priority and a design is willing to sacrifice speed in a variety of ways for a comfortable ride.

On that continuum, the Melee is certainly a fast race bike. It's aerodynamic and the geometry is close to other bikes in the same category. That feeling of fun I picked up on though, that's there as a choice. It's there because those who work building bikes for Enve prefer a bike to ride like that. Instead of only considering the racer, Enve is making a choice to incorporate race specific design elements into a bike for a broader rider profile. There's another aspect though. Unlike some brands, Enve is also a manufacturer.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Nelson explained that matters in this context because bikes are equal parts design, engineering and production. Every brand starts by understanding the target customer profile. A team uses that data to identify a series of goals then works with engineers to design a bike. At a certain point, that design work will then get handed off to a factory and it's here that Enve feels it has an advantage.

Working with a factory to build a bike introduces another entity into the process. That entity has different goals, different experience, and a different process. Frequently there's also a different culture and language involved. That means the beginning of the relationship is always going to start with translating one team's vision to another team and that's never exact.

Nelson talked about that process in terms of degradation of concept due to translation. He explained to me that even in the best scenario you can expect to lose as much as 10%. In fact, for most teams, getting to 90% of the concept would be a huge win and would represent an extraordinary amount of work. Because Enve is also a manufacturer, for some products there's essentially no translation needed. On top of that, there are also advantages throughout the entire process.

With manufacturing in-house, Nelson starts his design process with a thorough understanding of the building process. Nelson and his team aren't designing pie in the sky ideas, they know the limitations of the production process and they can have those guardrails in place from the very beginning. Then, during the design process, there is fast and direct access to samples for testing. This back and forth, when paired with a specific corporate culture, is what leads to the feeling of the Melee. That's true despite the fact that the Melee isn't built in Utah.

Although Enve has extensive manufacturing capabilities, the Utah building is only so big. The Melee is being produced at a scale larger than what makes sense for Enve in-house manufacturing capabilities. That doesn't erase the advantage though. When it's time to work with overseas manufacturing instead of showing a design and asking to have it made, Enve can show a finished example. The team can work through every little detail, figure out how to make it, then use a finished product to teach a manufacturing partner how to do the same.

The production process

As I walked through this discussion with Enve about how manufacturing and design play off each other, it was conceptual. Nelson could describe how each piece works and why that was an advantage but it's hard to fully understand it. At the same time, the brand is rather proud of the one-piece SES Aero Handlebar that was quickly built at the request of Tadej Pogačar. That confluence provided the perfect opportunity to walk the factory floor.

Instead of more conceptual discussion, we used the one-piece bar as an example of the Enve production process. At each step I had an opportunity to talk to the passionate people involved and understand what was happening. Other factories around the world are doing similar work but the next time you think about a carbon fibre handlebar, you can think about how complicated it is.

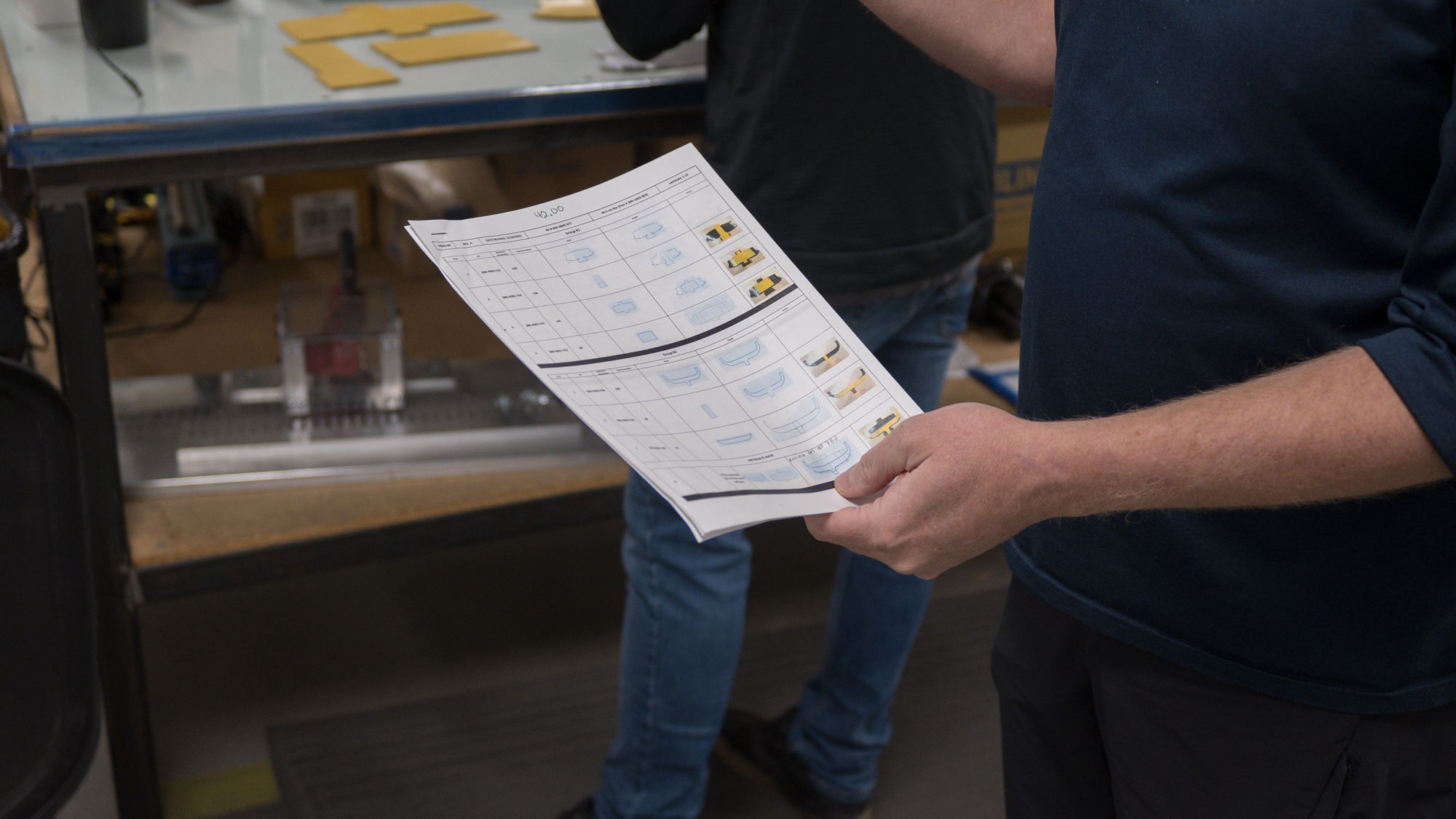

A ready to ride one-piece Aero Bar requires 43 pieces of carbon to come together. That process starts with a freezer. Carbon prepreg is a bit like very heavy fabric and it comes out of the freezer on a roll before feeding into a machine that cuts the necessary shapes. The cut pieces are then organised into groups with detailed instructions not unlike playing with Lego.

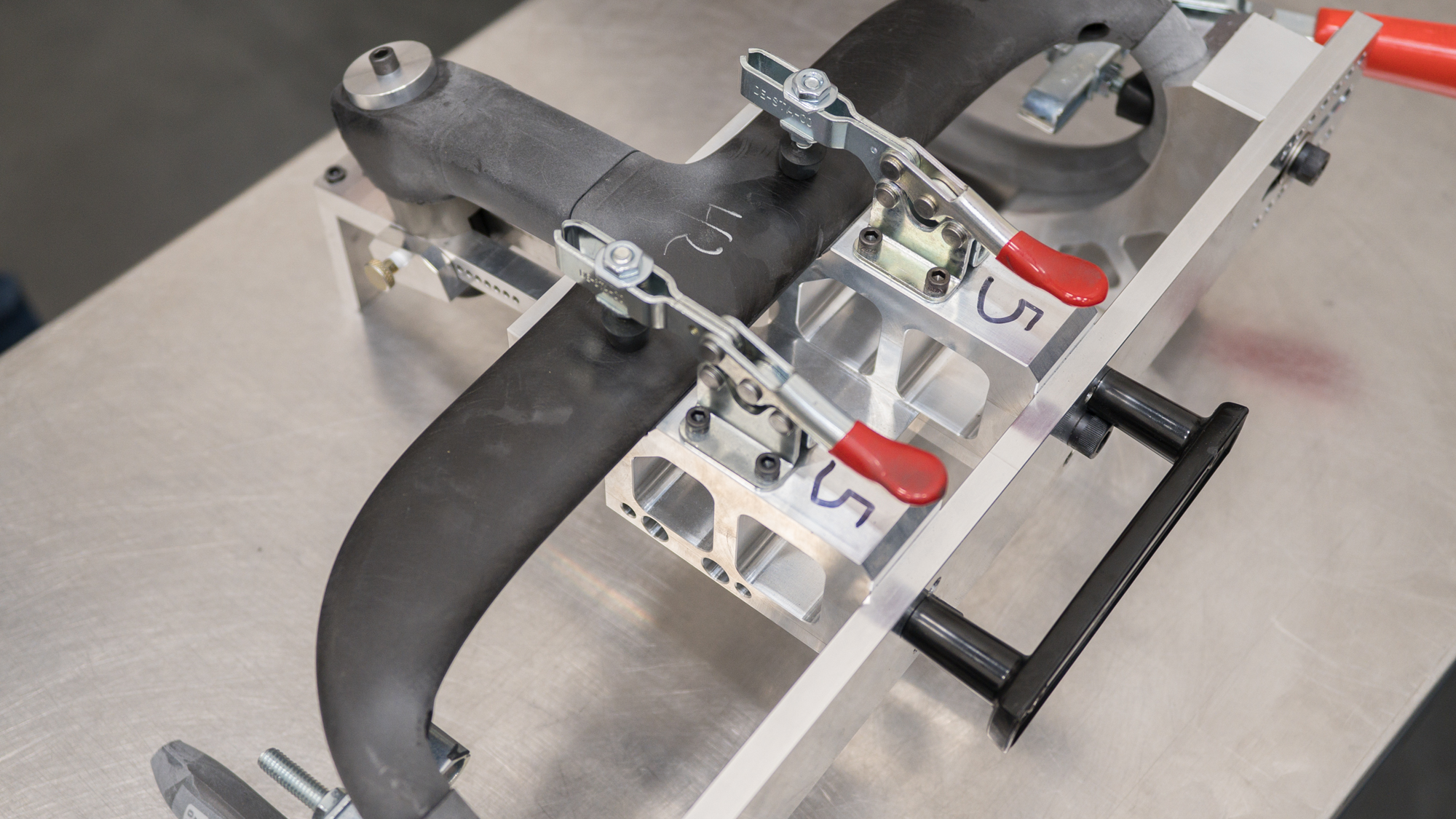

Like Lego, the next step is putting it all together. The backing comes off, all the pieces get stuck together in the correct order, and the bladders find their place among all the carbon. At this point, the handlebars look recognizable but flat and deflated. There are also separate pieces that make up the centre bar section, the stem section, and the drops on both sides. Each goes into a mould on its own at this point.

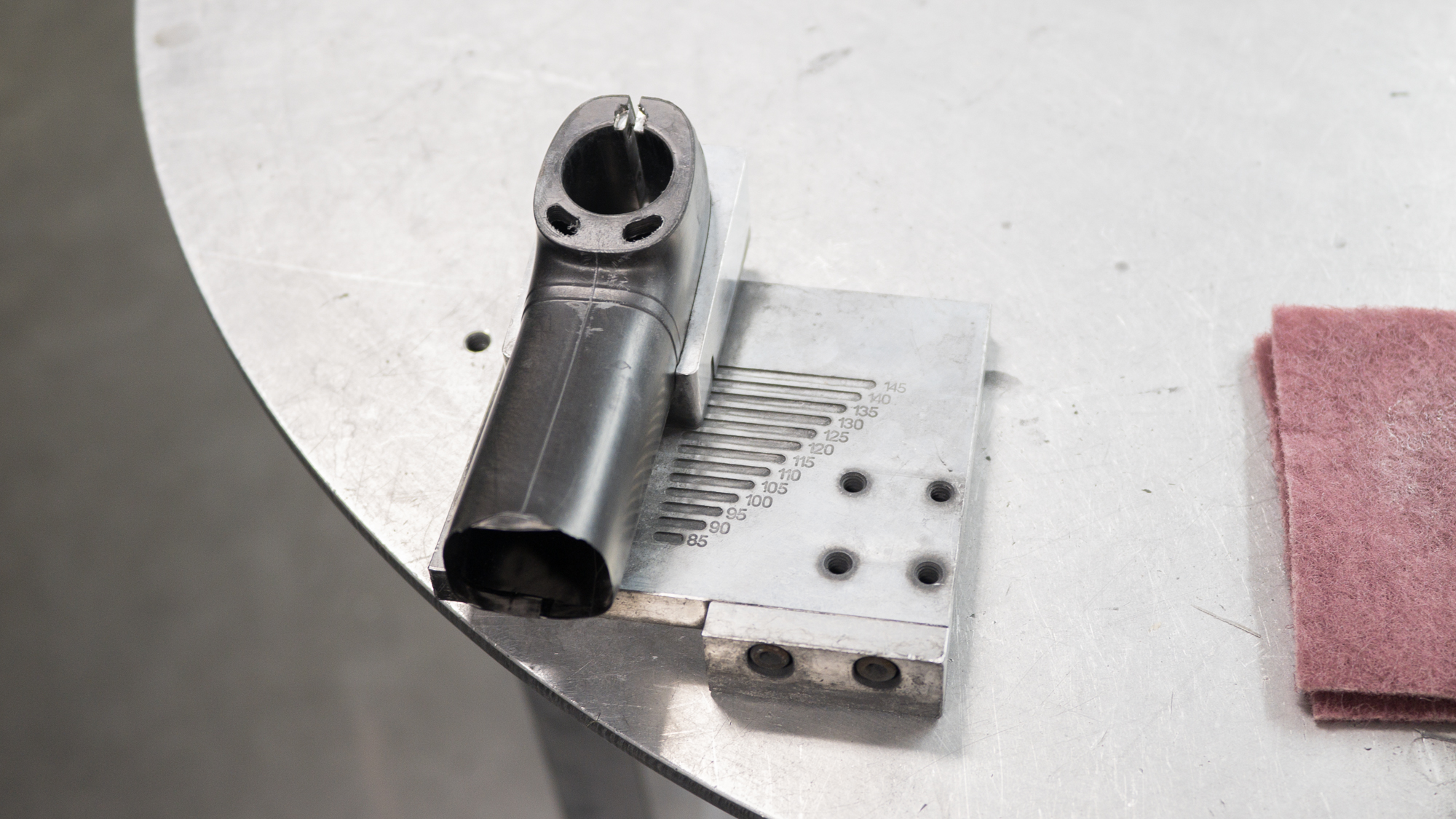

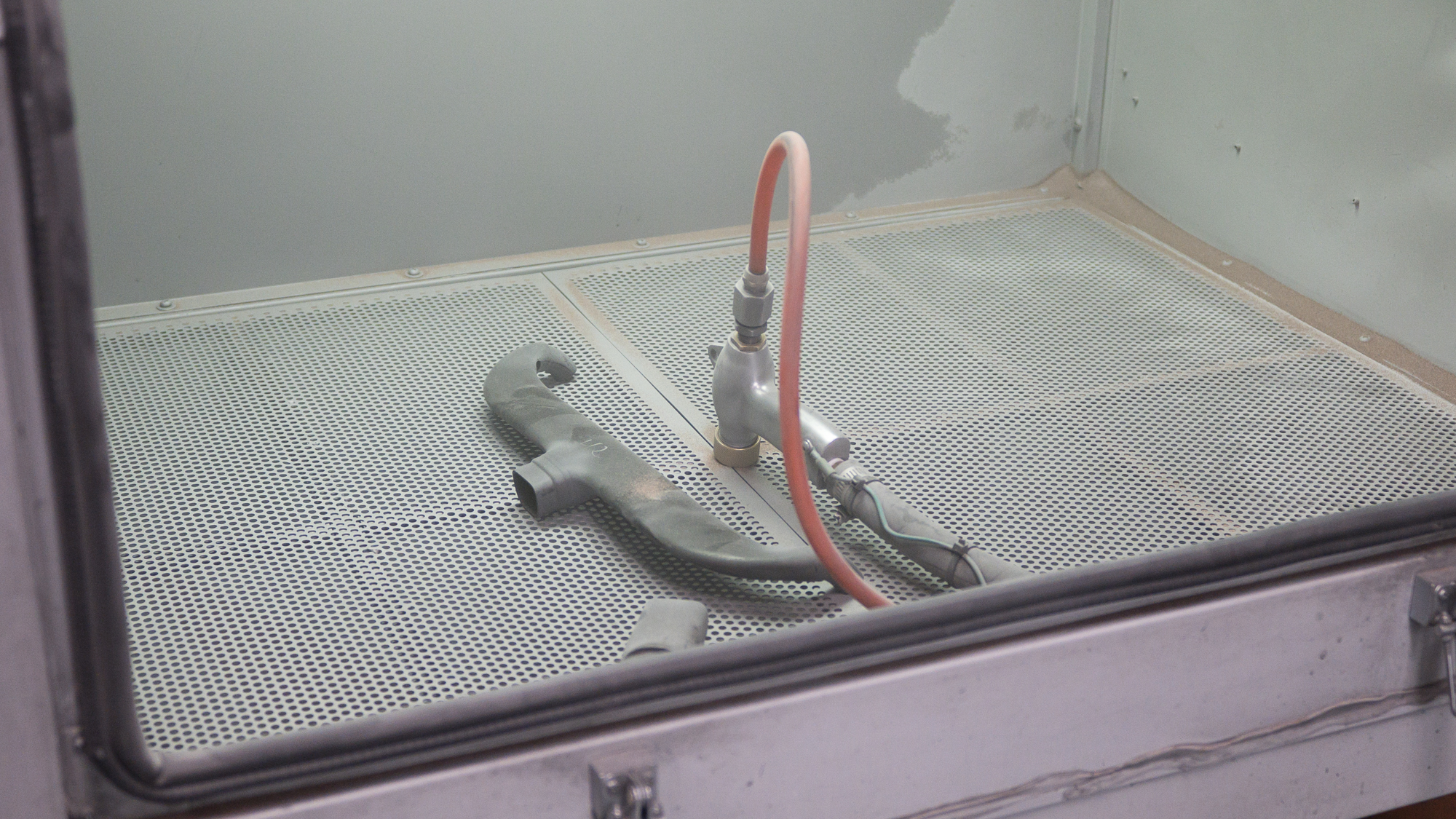

After heat and pressure creates the shape, it's time to remove the pieces from the mould. Each one comes out and heads to a prefinishing room and a bin of other parts. Prefinishing means a process of rough finishing. Processes like bolt hole drilling, flash line removal, and removal of extra resin turn the pieces into what is now called a blank. The process concludes by cutting each blank down to size using a jig then sandblasting the joints for better adhesion.

Throughout the whole production process, each piece remains trackable via a barcode. As the parts come into final finishing, that bar code gets added to a collection of other barcodes under a new master barcode for the final piece. If there was ever a failure, the barcodes would be there to understand exactly how and when that issue occurred. Once that final barcode is part of the new piece, the final step is sanding and painting before eventual delivery.

As you read through this process, a big takeaway is how handmade it is. Everything that Enve makes, including the Melee, is a meticulous process. While the end result is a high-end carbon fibre part, the production feels as simple as building models out of paper in art school.

It’s the people

As I learned about the way that Enve builds products, I heard a lot of pride. It's a feeling that isn't at all uncommon in the bike industry. I also talked about it in my article about the people behind Specialized shoes. Those are just two examples though, every brand I've ever talked to in the cycling industry is a small group of passionate people; people who care about the product they are creating and care about cycling in general.

From the Enve point of view, the Melee feels the way it does because of a competitive advantage. The brand creates products in-house and that allows for a level of flexibility that a lot of other brands can't match. That's not totally true though.

It's true that Specialized doesn't manufacture from its HQ in Morgan Hill, California, but it does have a carbon fibre and CNC prototyping facility right next door to the breakroom area that houses its foosball and pool tables. Even beyond cycling, though, every brand figures out a process that works, and Enve isn't totally different from an overall process point of view.

What is different is the desired outcome. The people under the Enve roof have a particular point of view. It's not right or wrong, better or worse, but it is unique. I personally prefer that my handlebars have a bit more flex, as Enve bars do, and that my bike feels fun even if that means giving up some small wind tunnel performance. If you also prefer that, now you know how Enve bakes it into the products the brand makes. Ultimately though, it's the people at Enve making decisions about what vision to present a consumer that dictates the feeling of the Enve Melee.

Josh hails from the Pacific Northwest of the United States but would prefer riding through the desert than the rain. He will happily talk for hours about the minutiae of cycling tech but also has an understanding that most people just want things to work. He is a road cyclist at heart and doesn't care much if those roads are paved, dirt, or digital. Although he rarely races, if you ask him to ride from sunrise to sunset the answer will be yes.

Height: 5'9"

Weight: 140 lb.

Rides: Salsa Warbird, Cannondale CAAD9, Enve Melee, Look 795 Blade RS, Priority Continuum Onyx