Earning the hardest national championship

Growing up in a world full of bikes, US 24-hour MTB National Champion Cameron Chambers certainly has...

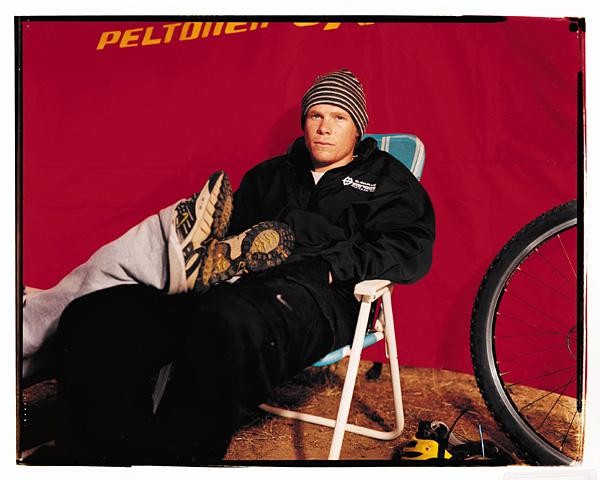

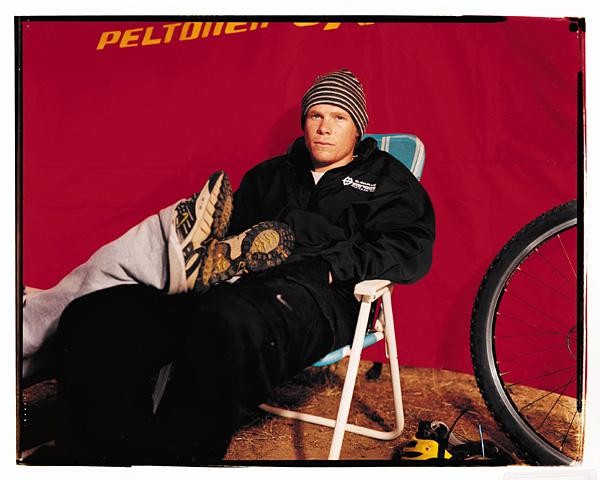

An interview with Cameron Chambers, July 15, 2005

Growing up in a world full of bikes, US 24-hour MTB National Champion Cameron Chambers certainly has the grounding every cyclist dreams of. Becoming national champion doesn't just happen, however, and Chamber's hours on his beloved singlespeed put him in good stead to outlast the others, and that's what he's done. Steve Medcroft caught up with Chambers and found out how everything's going for this rising star of endurance mountain biking.

In solo 24-hour racing, there has evolved an accepted standard tactic which calls for a rider to begin the race at or as close to World Cup cross-country pace as possible, hold positions through the night, then, if necessary, surge in the morning to chase down the leader or put the nail in the coffin of your competitors if you are the leader. Tinker Juarez, who came to endurance racing after a long and successful World Cup career of his own, really was the instigator.

So in the 2005 24-hour US National Championship race (May 28-29, 2005 in Spokane, Washington), it was no surprise when 24-hour big guns Tinker Juarez, Nat Ross and Chris Eatough screamed around the dusty and hot course.

Behind them on the trail sat Cameron Chambers, a 23 year-old Fisher/Subaru sponsored rider from Great Bend, Kansas on a two-niner, biding his time. "I don't follow that tactic," Chambers said after the event. "We all have so much fitness and it's obvious that we're all going to use every last ounce of it and no matter where I spend it in that race, it's going to be thin. I don't see the benefit in going that fast right away."

He maintained a philosophy of energy preservation. "I didn't think Chris would go as hard as he did because it was a course where drafting would be such an advantage. It was like a road race out there."

That philosophy turned out to be prophecy. The heat, which peaked at 95F during the first seven hours of the race, took its toll on the more aggressive trio. Ross crashed out. Juarez called it quits after sundown. As for Eatough, "I settled in at night, about an hour per lap, started seeing Chris on this section where the two halves of the course passed each other." Eatough was obviously suffering. "He was looking pretty worked - jersey completely open and pretty red." But he knew there was a lot of racing yet to be done. "The Chris that I've seen is pretty much bomb proof. I wasn't counting on him having trouble."

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

But sometime in the night, Chamber's crew seemed to come to life when they knew Chambers had passed Eatough as he rested on a pit stop. "On one lap in particular, my pit crew met me at the half way point and they were all pretty amped up. They were like 'you're doing great' but didn't say that I was in the lead yet."

From there, Chambers showed the poise of a veteran and stayed in front of the race until the final lap. "That last lap was really sweet. A lot of the support crew was riding around on the trail. Meeting me at different spots, cheering and celebrating already. I was tired. It was everything I'd been training for. I mean, it's not that I didn't believe I could do it but I just didn't think it was reality. All the cards just fell my way."

So who was this young challenger, NORBA's 2005 24-hour solo national champion? Not a newcomer it turns out. The Spokane race was Chambers 13th solo race and by no means his first win. But it all started in Great Bend, Kansas (pop. 15,000) when Chambers' father opened a bike shop (Golden Belt Bicycles), feeding the family's then growing obsession with cycling and providing a platform for Chambers to grow as a cyclist. "My Dad gave me a bike when the first bikes came - we put together a little Trek for me and I worked there off and on; sweeping floors and fixing flats - we get a tonne of flats out here."

It was on the dirt paths around town and the trails along the Arkansas River that Chambers learned to ride his mountain bike. "We had little trails in town but they were the kind of things where you didn't even know that what you were doing was mountain biking. We were just riding our bike down by the creek and building trails all over the place."

Chambers uncle was into racing and brought him along to a race in Warren, Kansas; about three hours away by car and the closest event to Great Bend at the time. "I was in seventh grade. We both raced in the beginner class. I remember that he and I were duking it out on the trail for our middle of the pack spots. I remember about what number lap I cut him off to get in front of him."

In high school, Chambers grew serious about the sport. "I was running cross country for the school and having success and started to realise that I seemed to have a knack for lasting longer than other people." Chambers was using his bike as training for running. But his heart was really in the bike. So combining an ability to ride for hours and a love of the bike, he started to train like he thought a top level mountain biker should.

"I just did crazy long rides. It is hilarious to look back and think about it because I even did some 24-hour rides for training. I remember doing like, there's this big park like 50 miles away from where I live and I'd ride my single speed over to it and do laps all day and then ride home. It was so stupid. But it kind of worked I guess. It actually feels like I rode a lot more back then than I do even now."

Somehow, he didn't tear himself down with all the work and began to post decent results. In a 12-hour event, he qualified for the 2003 24 hours of Adrenalin world championships in Whistler, Canada. "I hadn't even done a full 24-hours before that. I put so much training in leading up to it I actually had horrible saddle sores. I got a great start but rode the last three or four hours out of the saddle because I had the worst saddle sores. I ended up having to go to the doctor."

Chambers won his division and his 24-hour racing career was off in dramatic fashion. Which got the attention of the Fisher/Subaru racing team. They provided tentative support to Chambers at first then finally, full sponsorship. Which meant Chambers could focus less on finding a way to just prepare for, get to and survive 24-hour but could begin to focus on how to compete with the big dogs of the sport at the time.

"I didn't see myself on the same plain as those guys at first, and I don't know how bad Tinker or Chris beat me in that same worlds - two or three laps, maybe more - but just a month or two later at Moab, when I was not really thinking about results, only about getting a solid finish, I ended up passing Tinker and taking the lead in the race. It wasn't really until that point at all that I was like - I'm after these guys. I'm here riding with the top racer in the sport. Maybe I can do this."

What was that moment like; passing Tinker Juarez in a 24-hour race? "Surreal. I knew I was making up time but he had gotten way ahead of me and I'd gone out pretty slow. Each time I'd come through for a lap I would be told they were a rider or two ahead of me. I passed Nat Ross, who was in second, and right around the corner was Tinker climbing a hill in front of me. I rode the climb and just took off. Tinker didn't even know who I was. I don't know if Nat said something or Tinker asked about me because then he came chasing me down and Tinker and I were riding together for a while. It was pretty weird."

Chambers has long since grown comfortable with the idea that he deserves to be at the head of a 24 hour race. Which brings us back to the difference in his approach to that of the other top competitors.

The 'take it easy and steady' approach is really a by-product of his work with Carmichael Training Systems coach and elite US mountain biker Jason Tullous, another perk of being sponsored by Fisher.

"My training has completely changed. I cringe to think of the things I did when I was younger. I was a little skeptical at first. I had been improving on my own and having fun doing what I was doing and I didn't think a coach would really like my 'go ride the single speed forever' approach to training. And I didn't grow up in a cycling culture, like Boulder or Durango, where you learn the workouts and the hill intervals and all that. But Jason's been a huge help for me. Not having to think through every stage of training and understand everything I have to do to give myself the best preparation. Just to have somebody to bounce stuff off is great. Like this year, for example: I haven't done a training ride over six hours long. Everything's based on intensity now. And intervals."

With a more balanced and scientific approach to training, Tullous helps Chambers with a more balanced and scientific approach to his races. "For the national race, I did a hot lap on the racecourse the Wednesday before just to see what I could do. Jason and I devised up a plan to only fall about 20% off that time per lap during the race. We know that Chris has fallen 25 to 27% on his slower laps so we made a plan based around that. I maybe went out a little too fast but I was just drafting the whole beginning of that race but probably my energy output was below what I would have expended if I hadn't caught so many wheels. I did all I could to conserve energy in the first three hours. I just don't see the point of going anaerobic on the first lap."

Chambers says he understands why his rivals approach the race the way they do; "these races are so hard that to get that positive mental edge of the lead is a huge advantage." But he's sold on listening to his coach and taking the approach they do. "I feel like my body can really start to come along sometimes seven or eight hours into a race. I start turning some fast laps. I feel like it's an advantage I have so I might as well race to my strengths."

With the recent national championships added to Chambers' list of accomplishments in 24-hour endurance racing, he could be the rider to watch in the future as veterans like Juarez reach an age where they are thinking beyond elite-level competition.

Chambers is optimistic about the future and plans a steady schedule for the rest of the year. But what about beyond 24-hour racing? Does Chambers hold aspirations to break out into the more traditional cross-country or even the road cycling worlds?

"I'm always thinking about stuff but I really like what I'm doing right now. But then again, two years ago I didn't know it was going to lead to this so it's hard to say anything for sure. I love all forms of cycling but I think it would be pretty hard to get me away from doing this because I love it. Anyway, that's all the future and this is now, and I want to be a hundred percent focused on now.

So for now, Chambers will continue to focus on the endurance mountain-biking scene, travel the country with his wife (married one year) and try to represent his sponsor as best he can. And when you're twenty four and on top of the 24-hour world, maybe that's the perfect philosophy to have in life.