Dutch Dominance: What makes the Netherlands so successful?

Isabel Best examines the structures and culture behind the Oranje boom in women's cycling

Isabel Best is the author of 'Queens of Pain: Legends and Rebels of Cycling', and has contributed to Cyclingnews with feature stories 'Vital Statistics', 'Can women race a three-week Grand Tour?' and 'International Women's Day: 7 remarkable women who made their mark on cycling's history'. You can follow more of Best's historical writing on Cyclingnews during the 2019 season.

The colour à la mode of spring/summer 2018 was orange. Seen everywhere that mattered, it continued into autumn/winter, and looks set to remain on trend through 2019.

Last year, Dutch riders and/or Dutch sponsored teams won two thirds of all Women's WorldTour races. They dominated the World Championships in Innsbruck, Austria, with a clean sweep of the podium in the individual time trial and a crushing victory in the road race. If that wasn’t enough, they also took the junior ITT.

Throughout the season, the battle for WorldTour points was a purely Dutch affair, with Annemiek van Vleuten, Marianne Vos and Anna van der Breggen taking the top three spots, while Dutch teams took first and third place in the team classification. Mitchelton-Scott, the Australian team in second place, were there largely thanks to Van Vleuten’s efforts.

Dutch women took the most prestigious races on the calendar, from spring Classics like Strade Bianche, the Tour of Flanders, Flèche Wallonne and Liège-Bastogne-Liège (all of which fell to Van der Breggen) to the high-summer specials of the Giro Rosa and La Course (which went to Van Vleuten). And they did it with such panache. Who can forget Van Vleuten’s dogged pursuit of Van der Breggen in the final 14km of La Course, finally overtaking her by barely a second on the finish line? Or Van der Breggen’s invincible strength, riding the last 39km of the Worlds road race on her own to win with a jaw-dropping margin of 3:42? Or Van Vleuten’s utter grit in the same race, riding through the pain of a broken kneecap to finish in seventh place?

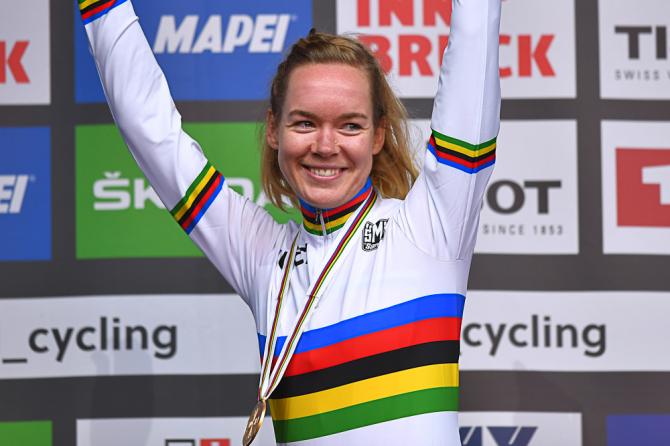

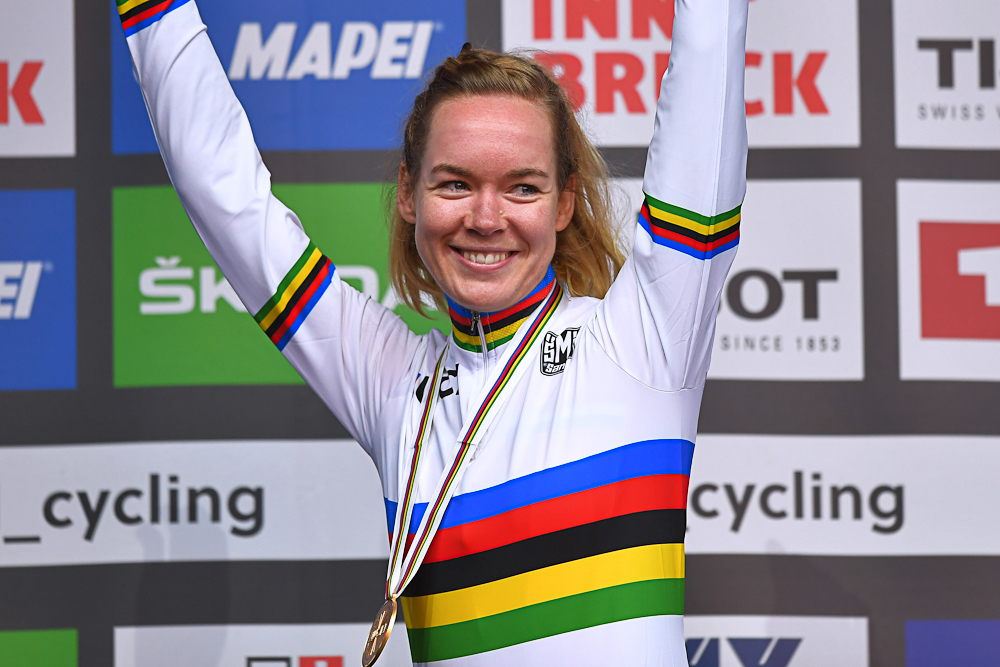

Anna van der Breggen on her winning ride in Innsbruck

Many countries have had their great moments and their stars – think of the Lithuanians in the early 1990s, the Germans in the 2000s or the British track riders in the last decade. The Dutch, however, have always been strong. They top the World Championships road race medals list, with 11 gold, 14 silver and 5 bronze medals – 30 in total compared to France in second place, with 17. They hold four Olympic road race victories out of the nine that have taken place since 1984.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You can trace a direct line back from today’s champions to 1966, when Bella Hage won the second-ever Dutch national championship, planting a stake in the ground with her family’s name on it. For the next decade, she and her younger sister Keetie swapped the national title between them. In between dominating races on home turf, Keetie won 19 medals at the Worlds, of which six were gold, and took two consecutive editions of the premier women’s stage race, the Red Zinger (later the Coors Classic), beating the queen of American women’s racing, Connie Carpenter-Phinney.

"She was feisty, tough and relentless on the bike," Carpenter-Phinney recalls in 'Ride the Revolution: The Inside Stories from Women in Cycling'. "If you have ever pushed yourself on the bike to a very high level and had someone take off and attack you from that level – well, that was Keetie. She could break my chops just about any day of the week."

When Keetie and Bella retired, their youngest sister Heleen picked up the baton, winning three stages and coming second in the inaugural women’s Tour de France in 1984. By then, there was more than a team’s worth of impressive Dutch racers, with riders like Tineke Fopma and Petra de Bruijn, world champions in 1975 and 1979. There was Heleen’s teammate Mieke Havik at the 1984 Tour, who won five stages. There was Hennie Top, later hired to coach the American women’s national team in the hope she might pass on some Dutch brilliance.

The 1990s were dominated by Leontien van Moorsel, with 10 World Championship titles and four Olympic gold medals to her name, and her arch rival Monique Knoll, also an Olympic champion. When those two were just about done, it was Marianne Vos’s turn to shine. When people compare Vos to Eddy Merckx, they aren’t exaggerating. There’s a room in her house stuffed to bursting point with all the medals and jerseys she has won, in just about every discipline: road racing, time trials, stage races, sprints, track, cyclo-cross and mountain biking.

Vos is still one of the best riders in the peloton, despite struggling with health problems and injuries in recent years. As her crushing dominance has waned, Van der Breggen and Van Vleuten have become more prominent, yet these three champions represent but the crest of a wave of Dutch talent, with riders like Ellen van Dijk, Chantal Blaak and Kirsten Wild – to name but a few – also dominating on the world stage.

"Their Nationals must be harder than the Worlds!" quips Marion Clignet, a former French pro, who won multiple World Championships and Olympic medals herself. "I’ve got the most amazing respect for them. Look at Van der Breggen, Vos... It’s all such class. What can you say?"

The Dutch junior women's squad at the 2017 world championships

A cycling nation

What makes the Dutch such dominant riders? Perhaps it starts with the fact that the Dutch own the most bikes per capita of any country in the world.

In the Netherlands, cycling is a typical, daily activity – not a specialist, off-beat sport. More importantly, it’s just as normal for women to ride bikes as men, with 55 per cent of daily trips made by women. This has a fairly straightforward consequence in terms of how female cyclists are perceived.

"You don’t question whether it’s a girl thing or a boy thing; you go and you do it. They have an incredible structure for cycling, so they use it," observes Clignet.

She adds that excellent bike handling is second nature to regular Dutch cyclists. "You pass a group of women who’ve gone out grocery shopping on the bike path and they hold their line, whereas you do that in France and you risk getting knocked over."

Club culture

"Most of the girls who are now at the top, when they were young they trained at a club," says Thorwald Veneberg, manager of the Dutch national team. He stresses the importance of the club structures, "but also the volunteers", who are mostly parents and trainee coaches. "That helps to give a safe and enjoyable environment to stay in and go on to racing."

Martin Vestby, head sports director of Van Vleuten’s Mitchelton-Scott women's team, is very familiar with Dutch cycling culture, with the Norwegian having ridden for a Dutch team himself.

"They have a lot of big clubs who take care of young riders from a really young age," he says, adding that most clubs are extremely well provided for, with things like training tracks that might be 1.5-3km long. "It’s like a park for cyclists. The younger generation starts there and rides small criteriums in quite big groups. They start from a young age. A lot of other countries are afraid of letting their kids out on the streets, and these clubs can run this training on closed circuits."

He also stresses the importance of the social side of club life, arguing that most girls don’t want to be the only female in a large group of boys. In the Netherlands, Vestby explains, there are a lot of girls who take up cycling from a young age. "I think that’s probably the starting point for building a strong foundation. To get a lot of top riders you have to have a lot of young kids to start with."

Vestby contrasts this with his homeland: "Norway is a small cycling country and the challenge there is that girls get lonely in the clubs when there’s just one or two of them. As they get older, they miss that social part and they play football or handball, where they can be together with the rest of their friends."

It’s no coincidence, on the other hand, that Norwegian women smash the international competition when it comes to cross-country skiing – a popular national sport "where you have good education and a lot of girls participating".

Investing in children

The high volume of very young female (and male) riders in the Netherlands gives children an opportunity to learn how to race from a young age.

"With having so many of them, they can compete at a younger age in bigger pelotons," Vestby explains. "There are a lot of races for young riders."

A prime example is the European Junior Cycling Tour Assen – a children’s stage race that takes place over a week in July. "I myself have participated in the Tour of Assen," says Veneberg. "It has a very long history. From the age of 8 until the age of 15, boys and girls are mixed, with the girls riding one age group lower, so girls aged 11 ride with boys aged 10."

Race leaders in the different age categories get to wear a yellow jersey, just as in the Tour de France. Another similarity to Grand Tours is the international nature of the event. In 2019, more than 800 children will participate from 22 countries.

One of the most famous former participants is Marianne Vos, who, unsurprisingly, won everything in her first year.

A young fan watches the Dutch women dominate in Innsbruck

Infrastructure for developing talent

"I'm very proud to be from a progressive country that gives equal chances to men and women," Van Vleuten told the press after winning the individual time trial at the World Championships last year. "I think we showed that we are professional with women's cycling in the Netherlands and, in general, with sports in the Netherlands. Maybe some countries are a little bit behind with women's sports."

Dutch girls don’t just have access to great clubs; as they get older there is plenty of support to help them achieve their potential as athletes. "If you reach a certain level then there are a lot of possibilities in Holland, from semi-professional to full professional," explains Veneberg. "The infrastructure is very good, from clubs to professional teams."

The Netherlands can boast five pro women’s teams this year. While not all their riders are Dutch, there’s no denying these structures create more opportunities for local riders than countries that only field one professional team, as is currently the case in the UK, Australia and Norway.

The Dutch federation itself routinely sends promising riders on training camps. For example, younger riders go to the Belgian Ardennes, where they can gain valuable experience in climbing and descending. At the same time, camps allow the federation to conduct tests to identify future champions. At elite level, there are camps to prepare for major races; last year the national women’s team took two trips to Austria to prepare for the Worlds.

Such investment and support shouldn’t be remarkable for a national federation, but it is sadly not the norm in women’s cycling.

Nicole Cooke recently stated that British Cycling had failed to organise a single women’s training camp in advance of the 2011 World Championships. This was the year before the London Olympics, at which Cooke would be defending champion, and in which her teammate Lizzie Deignan (then Armitstead) would eventually finish second.

The story emerged while Cooke was testifying at the UK Parliament's Department for Culture, Media and Sport select committee’s inquiry into 'Combatting Doping in Sport', in the context of the mystery package delivered to Team Sky at the Critérium du Dauphiné in 2011. Simon Cope, the man who delivered it, was, at the time, the British women’s road team coach, yet British Cycling appeared to have no qualms about him taking several days out of his actual job to act as a courier at the behest of a commercial men's team.

Anna van der Breggen and Ellen van Dijk

The importance of rivalry

Vestby points out that large numbers of riders inevitably lead to greater competition, which "really lifts the level higher again". In countries with fewer female riders, he says, "it’s 'easy' to get into a national selection and you don’t get that same competitive climate as there is in Holland".

René Koppert, a retired pro who runs the Dutch Cyclist of the Year Award – a glitzy end of year affair that gets covered on national TV – cites the example of the bitter rivalry between Van Moorsel and Monique Knoll in the 1990s, which led to Knoll leaving the national team in order to launch her own women’s team. With her commercial sponsors, this marked the start of a professional women’s scene in the Netherlands.

"It developed cycling," says Koppert. "With the start of Monique Knoll’s cycling team, the women started to earn a bit of money. Infrastructure was developed because of their success, and it gave the younger riders a chance to develop themselves."

Role models

When Rozemarijn Ammerlaan won the junior ITT at the World Championships in September, she told journalists she was especially delighted to have won on an old bike of Van der Breggen’s. "It was her old Giant from a lot of years ago when she raced with the development team at Rabobank," she explained. "They sold the bikes and so I bought it. Her name is still on it – that's really cool."

Veneberg explains that young Dutch riders have never been short of role models. "We have a history of strong women’s cycling," he says. "Our girls have always had a role model, so they always have reasons to start cycling – 'I want to be like Keetie Hage', or, 'I want to be like Leontien van Moorsel' - and now Anna van der Breggen or Annemiek van Vleuten."

The Keetie van Oosten-Hage Trophy, which is the award given to the Dutch female cyclist of the year, has played an important role in this celebration of female champions. It was created in the 1970s, Koppert explains, after Keetie had won the World Championship road race for the second time.

"Back then we only had a prize for the cyclist of the year, and they wanted to give the prize to her. But the board of the committee didn’t want a female to win, so they decided to form a new prize, the Keetie van Oosten-Hage trophy, and they gave it to her. Since then, every year there’s also the female cyclist of the year."

While "women’s cycling is very small", in terms of the numbers of professional riders, in the Netherlands "it has a huge publicity impact", with riders like Vos and Van Moorsel household names.

But it’s not just in cycling that female athletes are celebrated. "If you look to the Olympic Games, most of the medals won by the Netherlands are won by females," Koppert adds. "Skating, football, hockey... There are many sports in which Dutch women are dominant. So there’s rising interest in women’s sport and increasing opportunities."

Professionalism and culture

It’s one thing to excel on a professional team where you are clearly defined as the protected leader, but what happens when bitter rivals from different teams have to collaborate on a national team? Famously, Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali once lost the World Championships when it was theirs for the taking, because neither could stomach the thought of the other one winning.

One of the striking things about the Dutch team at the 2018 Worlds was that practically all the riders had a good chance of winning the race. Yet they managed to put aside their personal and commercial rivalries to help the best rider on the day. This is apparently not the exception, but the rule in Dutch cycling.

"They are really professional," says Veneberg. "Compared to the men, there’s no difference."

But how did Veneberg manage the two great riders and rivals of the season – Van der Breggen and Van Vleuten – at the Worlds?

The 2018 Dutch World Championships team

YouTube footage of their awkward embrace after the race spoke volumes about Van Vleuten's bitter frustration at the crash that destroyed her chances of winning. It wasn’t the first time it had happened, either. If she hadn’t suffered what could easily have been a fatal accident in Rio, she would almost certainly have won the 2016 Olympics, which in the end went to... Van der Breggen.

"We have conversations," says Veneberg. "Don’t put it under the table. Just talk about it. They both – and all the other women – say, 'Yeah, I want to win, but it’s more important that one of us wins.' That’s the main thing they say to each other. The worst thing that can happen is that one orange lady rides against another orange lady. They really hate that. The main goal is that an orange lady wins.

"They’re really forward; they say what’s on their minds," Veneberg adds. "That’s sometimes hard, but it makes it clear to everybody."

When riders are less up front, Veneberg suggests, managing a team can be more complicated. "I lived in Belgium and I really experienced this – that people don’t often say what they mean or what they think, and for us that’s complicated. We want to hear if something is not good and then we can do something about it – without being offended."

Vestby talks about this directness with regard to Van Vleuten – the only Dutch rider on the Mitchelton-Scott team – and her mostly Australian and New Zealander teammates. "They 'walk a little bit around the porridge,'" he says of the Australians. "In Norway, we have this saying that if you’re really straight, then you just jump into it."

Van Vleuten and Vestby evidently like their porridge. "I think Scandinavians are a little bit more direct in how we speak to each other, and that’s close to the Dutch who are maybe on the extreme side of it." Fortunately, the Australians are used to racing in Europe. "They have been around so much that they understand the differences as well."

Indeed, most riders seem to enjoy racing against the Dutch. American rider Marianne Martin, who won the inaugural Tour de France, has surprisingly fond memories of her Dutch rivals, even though they won all the flat stages and attacked her relentlessly in the mountains. "They were fabulous sportifs," she says. "They would always say 'congratulations' or 'good race'."

Marion Clignet remembers being similarly taken aback by her Dutch rivals' friendliness. "Contrary to other girls, they were really nice girls, and would encourage you. We would go tooth and nail to the line, and after the race we moved onto something else," she recalls. "It seemed odd to me at the beginning that we could actually be friends with each other and be competing against each other. I think that’s part of the Dutch education."

Clignet remembers racing in Brittany, the heartland of French cycling, where there are races every weekend, and the Dutch would drive down there and sock it to the French.

"They had their sprinters and their climbers and their lead-out riders. That degree of coherence was still unusual in women’s racing. They always seemed very organised, you know – a meeting before and a debrief afterwards. It seemed very professional and very well done. The impression I definitely got with the Dutch was that it was a team. They raced as a team and they looked after their leader, and that was definitely something that commanded respect."

Veneberg thinks the main Dutch attribute is their work ethic. "If we look at how they train and live for their sport, it’s really all or nothing, and I think that gives us an advantage."

Anna van der Breggen in the rainbow stripes after winning the Worlds road race in Innsbruck

Why don't other countries succeed?

There are many ingredients in Dutch success that are not unique to the Netherlands. It’s puzzling, for example, that the Belgians don’t play a similarly dominant role, given the importance of cycling in their national culture and the fact they taught Dutch women how to race. When Bella and Keetie Hage started out in the late 1960s, they learned everything in the explosive Belgium criterium races held on cobbled city centre streets.

Belgian riders were mercenary and fast, and, with an extra decade’s racing experience in the bag, they boasted multiple world champions. In contrast, Dutch races were relatively short, tame affairs. Until Keetie and Bella really got going – and Dutch race organisers had to make things more difficult – the Belgians would cross the border and win everything.

Even though they also have a good club structure, Vestby thinks the Belgians "are quite far behind compared to the Dutch", which he puts down to them being "a little more old school". Which is a polite way of saying they still don't value women’s racing.

"It has started to change in the last five years, but it’s still a men’s world," Vestby argues. While there are many clubs and race organisers at grass-roots level making a terrific effort, "in general I think they look a little bit down on female cycling".

On the other hand, in Scandinavian countries, known for their promotion of women’s equality, cycling just isn’t such a mainstream sport. As for the French, it’s probably best not to get Clignet fired up on that subject.

"In France they organise the biggest bike race in the world, but they do fuck-all for women," she says. "The problem begins with the mindset at the federation, which, even though it recently appointed a female vice president, Marie-Françoise Potereau, also seems to consider it necessary to launch an initiative on the féminisation du vélo. Already that’s a term that drives me nuts because what the fuck does that mean?"

The message is implicit: cycling is a men’s sport. Having grown up in the US in the 1970s and 80s when women’s cycling was experiencing a boom, and having been drawn to cycling after watching the inaugural women’s Tour de France as a teenager, Clignet is of a culture and generation that never questioned the existence of women’s cycling.

"I wish the French federation would pull their finger out and go to visit the Dutch and see what they’re doing, and see what they could learn from them," says Clignet. "But the French think they don’t need to learn from others, so it’s not going to happen."

Ironically, one of the greatest female riders of all time, Jeannie Longo, was French. The French also created the first women’s stage races in the 1950s. There have been many other brilliant French riders who have excelled on the international stage, like the sprinter Geneviève Gambillon – a Mark Cavendish of her era – or Longo’s rival Catherine Marsal, who now coaches the Danish women’s team.

But the majority of these riders had to make it on their own. One of the main criticisms of Longo’s many detractors – beyond the cloud of the EPO scandal surrounding her husband and coach, Patrice Ciprelli – is the fact she made no effort to help bring up other riders, to create structures or an environment in which women’s cycling could flourish. She takes on such criticisms in her autobiography by pointing out that she was an athlete, not a sports administrator, and one, at that, who had such a bad relationship with her national federation that she toyed with the idea of becoming American.

In Germany, cycling as a whole is still struggling from the doping scandals of the Ullrich/Armstrong era. The years of Soviet Union investment in sport are long gone, and the last athletes who came up through that system have long since retired. Other countries like Spain, Italy, the UK, Australia and the US all have strong individual riders or great teams, but none seem to boast all the elements of the Dutch formula combining national grass-roots interest in cycling, infrastructure, and commitment to gender equality.

Amy Pieters, Annemiek van Vleuten and Chantal Blaak after the women's road race in Innsbruck

Is there a Dutch racing style?

Does riding into the wind make Dutch riders stronger? Does the fact that the Dutch are very tall make them more powerful sprinters and time trial riders? Does the fact that women’s races are largely quite flat give them an advantage over, say, tiny Spanish climbers?

Vestby thinks those old generalisations – that the British are good at time trialling, for example, or that the Dutch are good at riding in the wind – are no longer so relevant. "Of course, you have quite a big influence from the kind of racing you grow up with, and of course in Holland they’re really good at riding into the wind and echelons," he says, but adds that you now also see strong Dutch climbers.

"It’s just about how they develop riders or take care of their different skills. If you’re not the best and strongest riding in the wind, they still have a system to see your talent and develop that in different ways. Of course, Annemiek grew up riding in echelons and criteriums, and handling that kind of racing," he adds, pointing out that she has also developed into an excellent climber with all the related skills.

Koppert doesn’t believe there’s a Dutch style of racing, but he’s a big fan of Marianne Vos, describing her as "the first woman rider with really good tactics".

"She developed tactics in women’s cycling enormously," he says. "Maybe I’m not allowed to say that, but she started riding like a man, in a much more tactical way."

He credits Vos with making women’s racing exciting. Comparing men’s and women’s races now, he argues, "most of the men’s races are very dull, very predictable", whereas women’s races, "are more attractive – there are more attacks. That changed enormously – in my view – due to Marianne Vos".

Clignet agrees. "I think, generally speaking, they have a better vision tactically," she says. "It’s something that’s more innate for them. I always felt there was no fear. They put their head down and they go. They know when to go, and that makes a huge difference."

Conclusion

"I think there are two ways to create champions," says Vestby. On the one hand, "you need thousands going through the ranks" before you can find the champion. If, like in the Netherlands, you have huge numbers of young riders, you’re already ahead of everyone else.

On the other hand, "If you don’t have that many riders starting from a young age, then you need to have a really good system to take care of the riders that you have, taking them through the ranks and educating them. In Holland, they have both. What you see now reflects the work that’s been done in Dutch cycling in the last 10-20 years. That’s bearing fruit, and that's why you’re seeing a lot of top riders from Holland.

"The best ones will always be best," Vestby points out. "If they want to, they can and they will survive. It doesn’t matter what environment they have. They will always have that urge and the willingness to make sacrifices."

Those sorts of riders – the Nicole Cookes and Jeannie Longos of this world – will get there no matter what.

"A hungry wolf always hunts the best," Vestby says, drawing on another Norwegian expression. But for collective success of the kind currently being demonstrated by the Netherlands, the culture and support needs to be there.