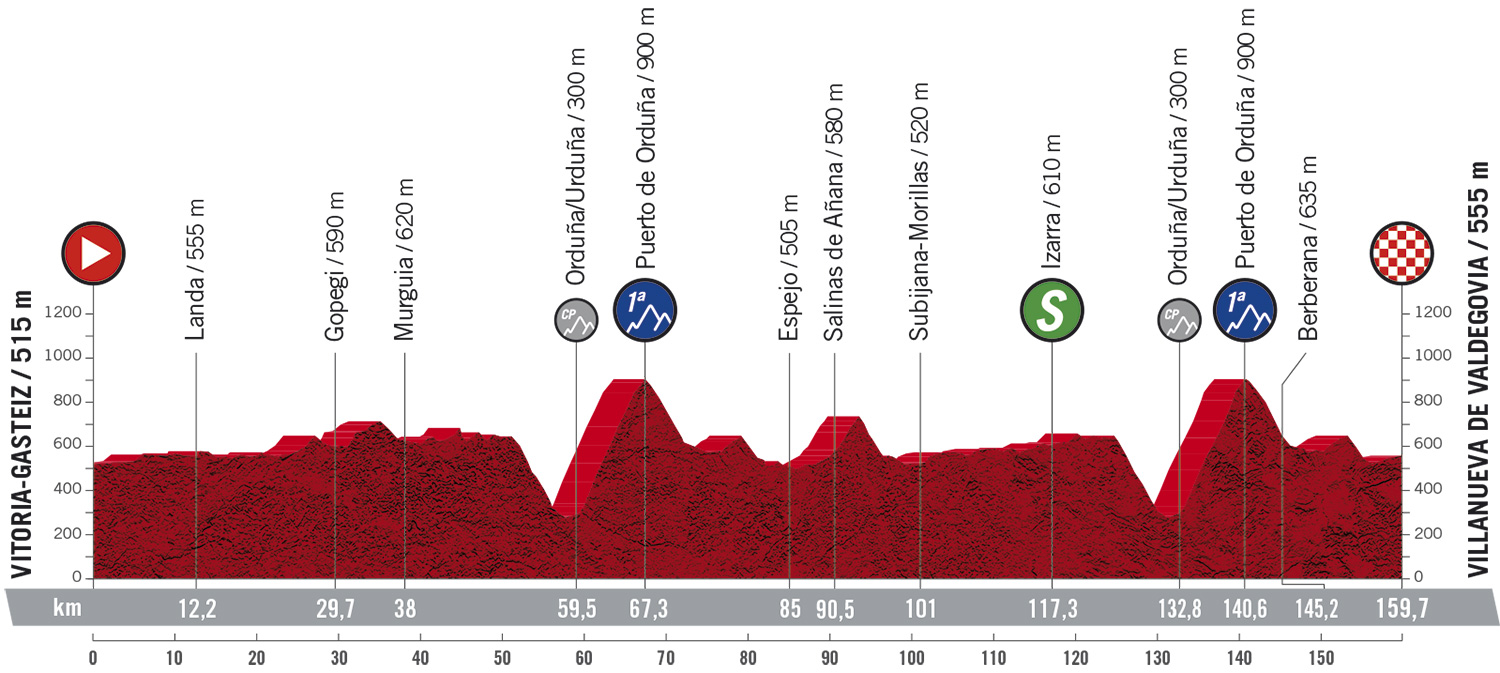

Double ascent of 'gear-wrecker' Orduña tests Vuelta a España peloton – Preview

Stage 7 sees a revival of the scarcely used eight-kilometre Basque Country climb with a long Vuelta history

Harder, higher, steeper: for the last couple of decades, the Vuelta a España organisers have excelled themselves at finding new, tough climbs across the Iberian peninsula for the race like the Angliru, Los Machucos or La Pandera. But on Tuesday, when the Vuelta resumes with a double ascent of the first category Alto de Orduña in the Basque Country, the race will be dusting down some of the most venerable pages of its own history.

First tackled in 1956, Orduña appeared regularly in the Vuelta through to the late 1970s, when the Vuelta began a lengthy avoidance of the Basque Country due to increasingly frequent attacks on the race by hardline separatist groups.

In 24 years, in fact, Orduña appeared no less than 12 times, eight of them between 1970 and 1978, often – thanks to the race almost invariably finishing in that era in the Basque Country – playing a critical role in the outcome. Curiously, though, it has never been used as a summit finish.

In 1956 on the second last stage of the Vuelta, Orduña was where outright winner Angelo Conterno shed the bulk of the opposition en route to nearby Vitoria - the Basque Country capital, where today’s 159 kilometre stage starts.

Spain’s top contender, Federico Martin Bahamontes, was pushed to beyond three minutes by that attack and Conterno gained enough time on local Basque hero Jesus Loroño to render a 30 second time penalty on the last stage irrelevant – for receiving pushes from various foreign ‘friends’ when he struggled on another Basque climb, the Sollube.

Loroño, second overall, protested vigorously at the finish at this unholy alliance, but even with the penalty the time netted by Conterno on the Orduña was just enough to keep the Basque at bay, by 13 seconds.

In 1968 another Italian star, Felice Gimondi, used the Orduña to scatter his rivals and ensure he won the Vuelta, thereby completing his set of all three Grand Tours. But the two most famous ascents of the Orduña, considerably shook up the general classification of the overall, yet failed to change the name of the overall winner.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In 1971, a blistering lone assault by Spanish great Luis Ocaña on the Orduña finally blew apart what had been, up until that point, one of the most mind-numbingly uneventful and boring Vueltas ever.

“An earthquake in the pedals of Ocaña,” was how ABC newspaper put it at the time, and Ocaña’s 50-kilometre solo adventure over the Orduña and onto victory in Vitoria shattered the tedium of an almost mountain-free race. Unfortunately, that very lack of major mountain stages in the final week left Ocaña unable to close the gap further on the Belgian leader, track specialist Ferdinand Bracke, who would eventually claim the victory overall.

1973 was a similar but more impressive story, as Ocaña managed to drop no less a figure than Eddy Merckx on the Orduña, in one of the few times – outside the famous 1971 Tour – when the Spaniard got the better of his arch-rival. Resplendent in his Spanish national champion’s jersey, Ocaña’s volleys of attacks on Orduña netted him a 27 second advantage on Merckx by the summit and, for another 30 kilometres en route to the finish town Miranda de Ebro, Ocaña kept Merckx at bay.

Although Ocaña was reeled in by the Belgian – who went on to win the Vuelta that year – and Bernard Thévenet with 27 kilometres to go, Merckx later recognised that the Spaniard’s performance on Orduña had been exceptional.

“I remember thinking, ‘this was a different Luis,’” Merckx recalled. “He was much stronger. I caught him before the finale, but he was just as impressive that year as he was in 1971.”

It wasn’t only Merckx who was impressed: the citizens of Miranda de Ebro subsequently re-named a railway bridge, under which the race passed, after Ocaña. The bridge has long since been dismantled due to a re-routing of the railway, but the memories of how Ocaña made Merckx suffer that day on the Orduña remain one of the Vuelta’s most legendary moments.

“Historically Orduña was considered the toughest climb in the Basque Country,” Jesus Gomez Peña, longstanding cycling correspondent of the biggest daily newspaper in the area, El Correo, and who has ridden up the ascent himself several times, tells Cyclingnews.

“It was only when climbs like Monte Oiz” – tackled in 2018 by the Vuelta – “in some of the wildest areas of Euskadi began to be tarmacked that it lost that unofficial status.”

“But for years, when it was one of the main roads south before the motorway was built, it was famous for being so steep and with so many hairpins that lorry and busdrivers called it ‘the gear-wrecker’.

7.8 kms long and tackled twice on stage seven this year, ‘the gear-wrecker’ is “relentlessly tough, with no resting places, or false flats” Gomez Peña says.

“It’s also very exposed at the top of the climb, which ends in the middle of some moorland, so the wind can make a big difference.”

“Apart from the last kilometre, which is easy, the slopes vary between eight and nine percent, almost never less, and there are lots of ‘ramps’ of between 11 and 14. It’s basically all built around a series of hairpins, too” – 15 in total – “which make it much harder because there are so many changes of gradient as a result.”

Some factors make Orduña less daunting: the approach road is not narrow or twisting, so there won’t be a huge fight to be at the front at the bottom, the road surface itself is good and the road, much of it running up the side of a densely wooded cliff, is a broad two-laner throughout.

The weather, in stark contrast to Sunday’s dreadful conditions, is supposed to be a lot better for Tuesday. Yet even if after the summit, the stage route continues with a straightforward, untechnical, drop off the sierras, there are only 19 kilometres to the finish in Villanueva de Valdegovía after the second ascent, so no matter the meteorology the pressure will be very high for sure.

The entire 2020 Vuelta peloton will have a chance to assess the difficulty of the climb the first time they tackled it on Tuesday – the summit is at kilometre 67.3 of the 159 – and on a day when Orduña is the only classified ascent, it should be all the more memorable.

Some of the more senior riders may remember Orduña from the 2012 Vuelta, too the one time it has been tackled since 1978, and when it was an early springboard on a stage finishing in Valdezcaray more than 100 kilometres further on: that day Cofidis Luis Ángel Maté, taking part in this year’s race, was first over the summit. The Orduña has featured very occasionally, too, in Itzulia, most recently in 2015.

What will be radically different to any previous ascent, of course, will be the lack of roadside support and noise. With anti-pandemic measures in place, the climb, like all the main ascents of the Vuelta, has been closed off to any fans. But as a clear opportunity to put new race leader Richard Carapaz (Ineos Grenadiers) through his climbing paces, with or without the public, Orduña qualifies with flying colours - and it has the history to prove it.

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.