Do I have to do a 20 minute FTP test?

The 20-minute test is long-standing, but it's hard to pace correctly and it's based on an unreliable calculation, so what are the alternatives?

When it comes to cycling training, the first and most important step to reaching your goals is understanding where you are right now. Knowing your current level of fitness allows you to ensure the subsequent steps are taken in the right direction.

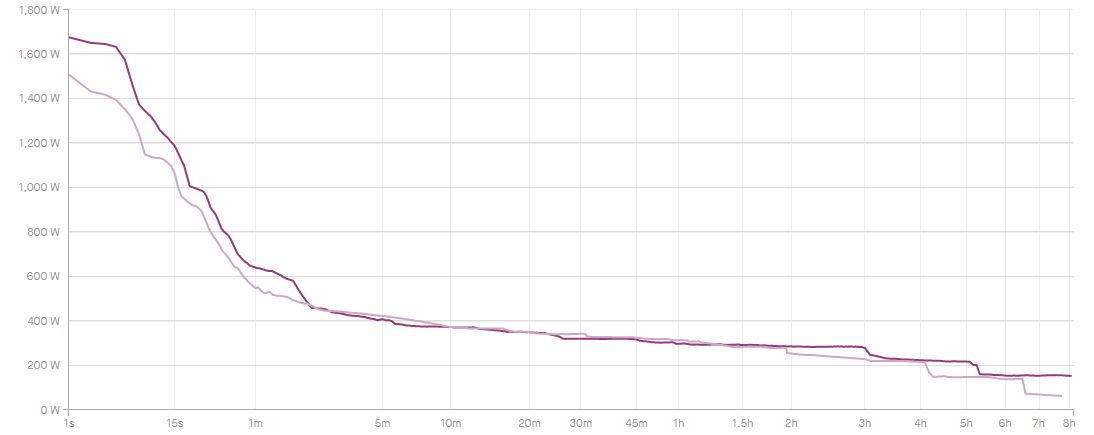

One of the most widely used metrics to quantify a rider's fitness is Functional Threshold Power (FTP). Pioneered by Hunter Allen and Dr Andrew Coggan, it is the measure of a your maximum aerobic capacity. In its most simple form, FTP is equal to the highest (Threshold) number of watts (Power) a rider can sustain aerobically (Functional), and is widely measured over 60 minutes.

With a known FTP, you can then extrapolate seven training zones, which include Active Recovery (up to 55 per cent of FTP), Endurance (up to 75 per cent), Tempo up to 90, Threshold up to 105, VO2 Max up to 120, Anaerobic up to 150, and Neuromuscular from there on up.

Training sessions can then be set to target those zones, focusing on specific energy systems to help you meet your goals. For example, if training for a time trial, sustained power - or threshold - will be the key area of focus, whereas a sprinter will focus more on neuromuscular power and VO2 Max efforts.

However, riding at maximum power for 60 minutes is incredibly difficult. Not only from a physical exertion standpoint, but also mentally. It's very easy to start too hard, putting the rider into VO2 Max territory, which means the latter half of the test will be below threshold, and ultimately the test will be a poor representation of one's functional threshold power. As a result, Allen and Coggan suggested that FTP60 could be determined as 95 per cent of the average power output in a 20-minute TT (FTP20).

Enter the 20-minute test

The 20-minute test is a less strenuous version of the same test. It follows the exact same structure, but as the name suggests, it lasts 20 minutes rather than 60.

It works on one basic assumption: the power that you can hold for 60 minutes is equal to 95 per cent of the power you can hold for 20. Therefore, the average power sustained in a 20 minute test is multiplied by 0.95 to calculate FTP.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

It is one of the most common ways to test, it can be performed both indoors and out, and it's used widely around the world, but it still comes with its downsides.

The downsides to the 20 minute FTP test

Despite being a third of the overall length, a 20-minute test is still difficult to pace correctly. Given it is a sustained effort, the first few minutes often feel easy, and it takes practice and experience to avoid going too hard too soon. As a result, it's possible that the average power over 20 minutes might not be representative of the maximum average you can actually achieve.

Moreover, the assumption that your 60-minute power is equal to 95 per cent of your 20-minute power isn't always reliable. The 95 per cent is a number based off averages, but for many amateurs, the power drop-off between 20 and 60 minutes can be much greater than five per cent, so those athletes might be better off using 92 or even 90 per cent. Their FTP would be set too high when using the 95-per cent rule.

The third is more a criticism of FTP as a whole. As we said at the start, performance exists on a spectrum, so calculating training zones based on a single metric can lead to inefficiencies. And finally, FTP can be irrelevant to certain disciplines. For example, a criterium racer will rarely hold a steady-state effort, even a solo breakaway rider will encounter corners that provide periods of rest followed by sprints well in excess of threshold.

The alternatives

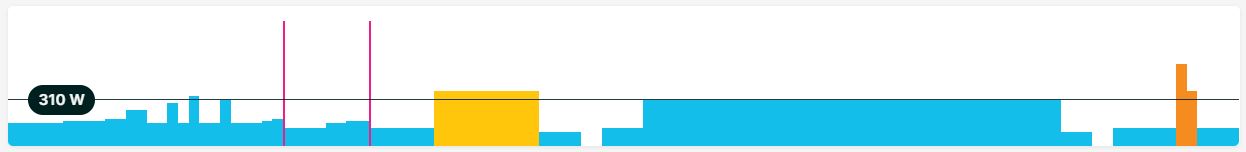

Eight-minute FTP test

This test includes two eight-minute maximum efforts, separated by a 10-minute rest between. It then takes the average power from both efforts combined and reduces it by 10 per cent to obtain FTP.

The benefits of this test are that it allows you to also see your VO2 Max power from each interval, as well as track improvements in repeatability by comparing the power drop between the first and second effort.

However, the downside to this test are that training zones are still calculated from the single metric of FTP, it can still fall foul of pacing errors, and it still uses a calculation based on averages, rather than your individual performance.

Ramp test

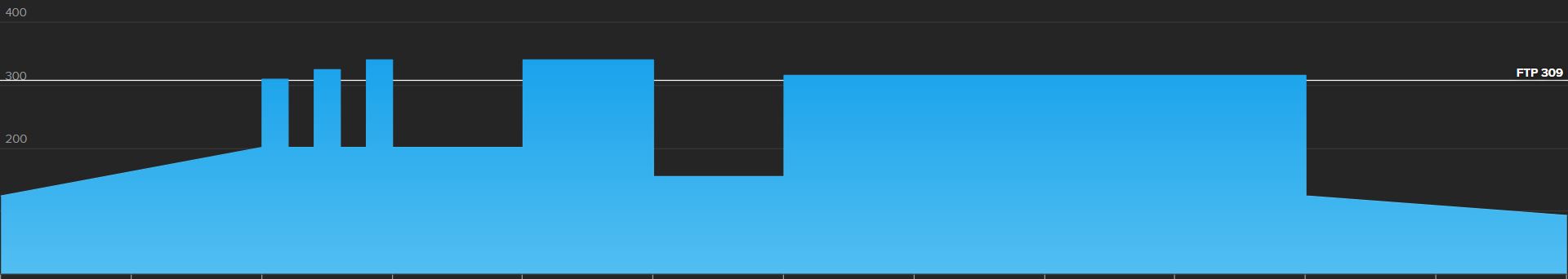

This test comes in various forms, but the general principle is always the same: a series of regular upward steps in resistance to be ridden until failure. Once you can no longer keep the pedals turning, a calculation is made to work out your FTP. The exact calculation depends on the structure of the test, such as how quickly the resistance increases and the duration of each step.

The benefit of this test is that it's impossible to pace incorrectly, since it's a test to exhaustion, so it's very beginner-friendly in that regard.

However, the downsides are that it's not accessible to all, since it must be performed on a smart turbo trainer, and once again, it uses FTP as the metric to work out all other training zones.

4DP® Test

4DP® stands for Four-Dimensional Power. It was developed by The Sufferfest, which now exists within Wahoo SYSTM.

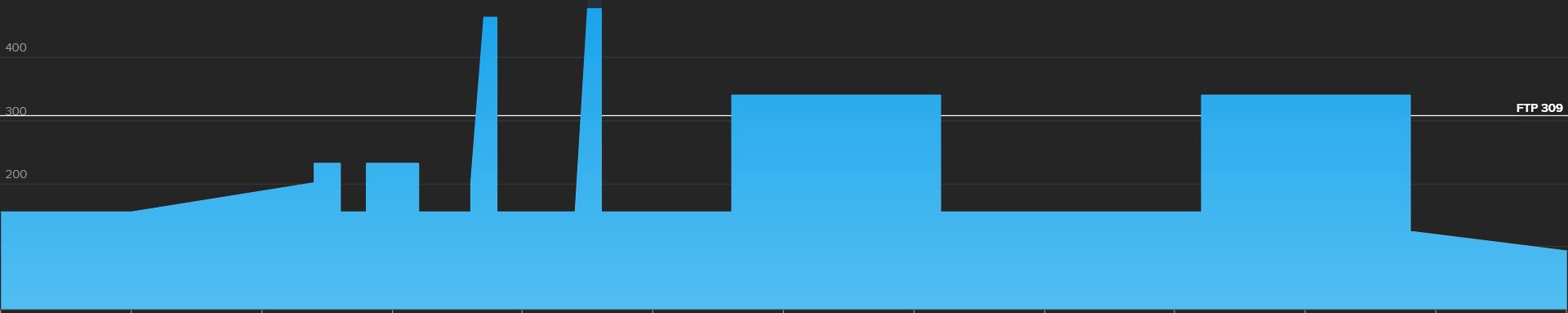

It is a four-part test that measures your Neuromuscular, Anaerobic, Maximal aerobic and Functional Threshold power capabilities via five-second, one-minute, five-minute and 20-minute tests respectively. The test is to be performed in one sitting and is designed to take into account the fatigue that will build throughout.

The benefit of this test is that it offers a more rounded overview of a rider's abilities, and as such, more accurately tailored training sessions can follow. For example, by testing your neuromuscular power, your sprinting sessions will be prescribed around your performance in that test, rather than based off a high percentage of your aerobic capacity.

However, as it includes long steady-state efforts, it can still fall foul of pacing errors. It's best performed on a trainer, but it's replicable on the road for those without.

Critical Power

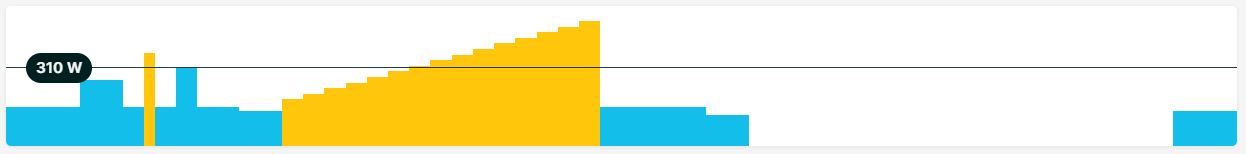

Critical power tests are designed not to calculate your FTP, but as the name suggests, your critical power. Both have a similar function, but critical power goes a step further by calculating both aerobic and anaerobic capacity.

It is tested using at least two maximal efforts, over 12 minutes and three minutes, but can also include additional tests to gain increased confidence in the result. A calculation is then performed to obtain your result, which is displayed as CP & W' (pronounced 'W prime'), where W is representative of your anaerobic capacity.

Once you've performed your tests, you can input the results into a critical power calculator to obtain the results.

The benefit of this is that it takes into account more than just one metric. It looks at a rider's ability over various time periods, and allows a rider - or coach - to prescribe workouts that are more appropriate to a rider's abilities. The downside here is that it requires a complex calculation to work it out, and once again, it relies on a rider's ability to pace the steady-state effort.

Other

Of course, there are a host of other, more detailed testing procedures such as a VO2 Max test, VLaMax, INSCYD and more, but these sorts of test typically require the assistance of a coach or lab environment, and as such, are inaccessible to the majority of riders.

Josh is Associate Editor of Cyclingnews – leading our content on the best bikes, kit and the latest breaking tech stories from the pro peloton. He has been with us since the summer of 2019 and throughout that time he's covered everything from buyer's guides and deals to the latest tech news and reviews.

On the bike, Josh has been riding and racing for over 15 years. He started out racing cross country in his teens back when 26-inch wheels and triple chainsets were still mainstream, but he found favour in road racing in his early 20s, racing at a local and national level for Somerset-based Team Tor 2000. These days he rides indoors for convenience and fitness, and outdoors for fun on road, gravel, 'cross and cross-country bikes, the latter usually with his two dogs in tow.