David Millar's cycling dream team

British former rider picks his nine-man team

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In a new run of features, Cyclingnews sits down with some of the sport's well-known personalities as they pick their cycling dream teams. This week it's the turn of retired British rider David Millar, whose 18-year career began with Cofidis back in 1997 and was punctuated by a doping ban from 2004-2006, after which he was a key part of the Slipstream/Garmin set-up.

The rules:

- Dream teams must feature nine riders, one of which can be the rider selecting the team. In which case they pick eight riders to join them.

- The riders picked must have all ridden with the person picking the team. That means you can’t just pick the eight or nine best riders of a generation.

Road captain: David Millar (Garmin)

My role in this team would be the one I had towards the end of my career, when I was a road captain, jack of all trades, domestique and someone who had the capability of winning if the opportunity arose. I really enjoyed that role and I took a lot out of it.

During the early part of my career, when I was seen much more as a leader, I was very hit and miss, but I became more consistent when leading in a disciplined fashion, and when I had a specific task. When I had the obligation to deliver as a leader, I didn’t really get that much out of it. When I had the duty to be ‘on it’ for the team I was much more reliable. If you left me to win for the sake of winning, to be honest with you, I couldn’t care less.

However, there was this sweet spot from 2009 to, say, 2013, when I really felt like I nailed that captain-style role. Every single race I was on it, and I had a job to do. That was when I was at my best. I enjoyed those four years because I had that job and I wasn’t just this flippant rider who was there just to race. There was more of a purpose.

Image courtesy of

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Sprinter: Mark Cavendish (Great Britain)

The first time I met Cav was during my ban. I was training in Italy and staying with Max Sciandri a lot and at the time Mark was winning a lot as an amateur. He was over in Italy, this little chubby Manx kid, and he was telling me, ‘fuck it - if I get to the finish line no one is going to beat me, no one has a chance.’ I remember being out training with him, we were pedaling up this this climb, he was just sweating all over the place, and there he was, basically saying he could take on anyone, even the best. I remember thinking ‘you’ve got no fucking idea’ but he was right.

He’s always believed in himself and even though there’s perhaps this plateau in his career we forget how good he is and how good he’s been over such a long period. He’s won 26 stages in the Tour and he’s still one of the most consistent sprinters in the world. Look at Marcel Kittel’s palarmes next to Mark’s, and it’s not even a drop in the ocean.

Because of his record, though, we’re not very forgiving of Cav when it starts to go wrong. I don’t think that bothers him that much and he still has a lot to give but he absolutely loves racing and being with a team.

I know that we were never on the same trade team but we raced together on a number of occasions for Great Britain, and of course we were at the Commonwealth Games together, on different teams but we still hung around together. That meant that I managed to see what he was really like, away from the intensity, and while the term isn’t used that often, he is very much a talismanic figure. He radiates energy.

A lot of team leaders are what I would call ‘mood hoovers’ and the entire team can be on edge because of that. If the team leader is in a good mood then the whole team is up but if the leader is in a bad mood then it can all go to shit. With Cav, whether it’s going well or not – and he does have his rages – he gives out this radiant energy. He’s generous in victory, and in many different ways. I’ve seen him be quite materialistic, which is quite old school. So he’d buy people watches but in a pure generosity of spirit he gives his teammates so much more. I know that it goes both ways, so if he’s pissed off he wears his heart on his sleeve but they’re much briefer moments than many people realise. He’s an asset to any team, even when he’s not winning because it’s good to be around him.

Not many will know this but after the Olympic Games road race in London, after we’d lost and he came back to the team he was really magnanimous. We all knew that we’d fucked up on many different levels that day. We were too confident and we’d even fucked up by winning the Worlds the year before in the manner that we did because it made us too cocky. We were on cloud nine and maybe the course in London was too hard for Cav, but we believed in him so much. Of course we needed the stars to align, and they nearly did but because we’d announced it so much we created the tactics and everyone raced against us rather than to win.

In hindsight I’d change nothing about that race apart from the fact that I would have gone radio silent on what we were doing. The euphoria of the moment; Bradley winning the Tour, Cav being world champion, Team Sky, four of our team winning stages in the Tour; Great Britain as a team had never had such a strong squad, and we didn’t know how to handle it. Perhaps we were too cocky and we nailed ourselves to our own cross. Cav, though, was gentle in defeat with us and that meant so much.

Team leader for GC: Christian Vande Velde (Garmin)

I thought about Chris Froome for this role but then if this is about the best team then I think Christian would get the nod. Chris is of course an incredible Grand Tour rider but he would dictate the make-up of the rest of the team, and for me, I’d want a more eclectic squad.

Christian, like many from my generation, was dropped into the sport at an incredibly difficult period, but I know that if he was born 10-15 years later he would have still been a legit Grand Tour contender. He had the weird genetics, he became hungrier in the third week of races, and he could do anything on a bike. On a purely physical level I’ve not seen many bike riders like him but because of the nurture of his career those factors were really beaten out of him.

For me, this isn’t just a dream team, it’s dream situation, so imagine these guys all coming up now and not having to deal with the stuff I and others had to – it would be amazing to see their nature given a real opportunity without their heads all being twisted and fucked up.

When I think about riding with Christian I think back to the mountain stage of the Tour in 2008. The field was down to around 70 riders and Christian would be the only one from our Garmin team still there. I was exhausted because I’d been racing full-gas all year but he would never complain. He’d be going back to the CSC car and Bjarne Riis would give him a bottle – Spanish teams would help him – and he was holding top-five in the Tour without any real help in the mountains. He was relying on good will towards him in the peloton. That says a lot about him.

Image courtesy of

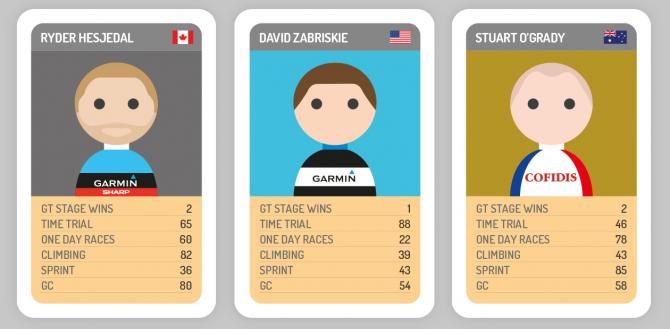

Climber: Ryder Hesjedal (Garmin)

He’s down as a climber but really you could put Ryder in nearly any role. He’s like a free electron and I love that about him. He’s set up wins for Dan Martin in the Classics, he’s won stages in races and of course he’s won a Grand Tour. You have to take him for the type of athlete he is, so if Christian is a born leader who likes being at the front and supporting guys, then Ryder is your maverick. Every team needs one of them because it gives you a lift and it can dig you out of a hole when you most need it. There were times at Garmin when we would all be at the front and Ryder would be at the back and thinking ‘I’ll just wait until it gets hard’. That was his style, his ethos, and he’s just not your prototype rider.

Before he joined Garmin the last time I had spoken to him was at the Vuelta in 2006. He was on Phonak and he was telling me that he’d had enough of Europe and that he was heading back to North America. I told him to stay because if he left he wouldn’t come back. Actually, he pulled out of the race that very day and left, which says wonders for my motivational skills and my ability to encourage a man to leave the peloton and switch continents.

But when he came back, you could see that maverick style was still there. The majority of the people of my generation, they tend to live in blocks: train, work, sleep, eat, race and repeat. With Ryder it’s just one long block. He just loves it. He rides his bike the whole time, travels the world, and for him it’s just a way of life. It’s different to others out there and hence the longevity to his career.

Co-captain: Stuart O'Grady (Cofidis)

I think it’s better to have two guys who can captain a team rather that just one and Stuart fits that role perfectly. He won Paris-Roubaix and so many other races, and he just had one of the biggest engines I’ve ever seen. Most importantly, he was just a born racer. I wanted to have a team that could win on many different levels, not just have one leader who if he crashes out means the entire squad falls apart, and Stuey gives you that.

He and I were similar in that we could be quite extreme off the bike with our partying but on a bike we used to race so hard. Despite what you might think he was a consummate pro, and everything from his kit to his respect within the peloton was second to none.

I remember at the Dauphiné in 2004 he won two stages, including the penultimate one. The night before that second win we were staying in some shitty hotel and we had a few beers in the evening. We were reprimanded the next day in front of the whole team and we were so angry for the dressing down we took. We knew we were in the wrong but sheer adolescence saw us attack just as the flag was dropped at the start of the stage. He went from the right, I went from the left and we both moved with 200 meters to go, just before kilometer zero. It meant we were clear just at the right time and I remember that I just put my head down for an entire hour. There were maybe 10 guys in the move and I just time trialled for an hour in order to make sure that we snapped the peloton. I went so hard I had to pull out of the race two hours later but Stuey won the stage. We were idiots, basically.

When he won a stage in the 2004 Tour, a few weeks after I’d been arrested and admitted to doping, he had the balls to dedicate his win to me. That was quite risky to say the least. He stood by me, more than many people, and he always has done. He’s a good man and he’s someone you want in your corner. He’s loyal and there’s not many like that in professional cycling.

Domestique: David Zabriskie (Garmin)

Give this man and job and he does it perfectly. When we had the yellow jersey at the 2011 Tour de France with Thor Hushovd, Dave was practically controlling the peloton all on his own. That was his natural habitat; to be out there time trialing or on the front working for his team. He hated road racing - I don’t think that’s any secret – but he was a phenomenal athlete who could read gaps like no other.

There are a lot of tough riders but in a lot of cases they’re not the smartest. It’s hard to find tough, clever guys but Ian and Dave were certainly like that. He could be massively fragile and he was beat down a lot during his career and I think he relied on Christian and myself to be these big brother-style pillars for him. He’s anti-authoritarian – as much as one could be – and while some might be worried about that in their team I think he helps with the chemistry and character. You need that mix, and Dave, while he doesn’t give a fuck about authority, he does care what his peers and colleagues think of him.

The 2012 season, and the fall-out, really hit him hard. I think it broke him and fucked him completely. Bless him. Physically I think he could have carried on for years but after that he just couldn’t deal with the shame. He’s one of the last people in the world who should have gone through that and it was a terrible waste to see him leave the sport like that. He never craved recognition or attention and I remember him telling me towards the end of that season, that he was going to ‘go out the back door’ and that he didn’t want people to know. A lot of people say they’re introverts but Dave Zabriskie was the real deal.

Image courtesy of

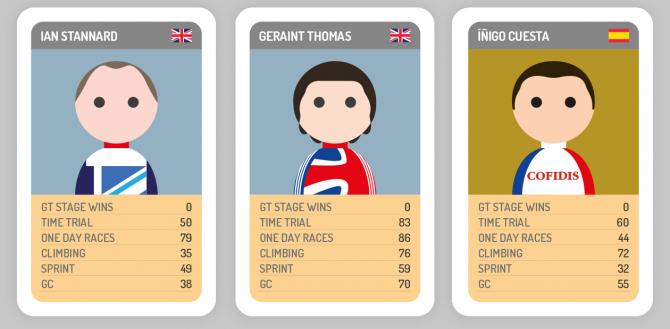

Domestique: Ian Stannard (Great Britain)

When I was living in the UK after my ban Ian must have been on the U23 programme. He alone came to train with me and he turned up at this little flat where I was living and he was just a unit. We did this three hour ride and just smashed it. It was this wet, cold day in the Peak District and that was the first time I’d met him. Everything was a race for him and even though he’s moved up into the pro ranks I don’t think he’s ever tempered his enthusiasm.

He’s becoming a rider who he has dreamed of being, and that’s a Classics rider. It goes against the British system in some ways, because he’s not a track rider, and he’s not a GT rider, so he didn’t fit with that ‘dream’, but at the same time he can help out guys like Geraint Thomas in the Classics, and he can work his socks off in the stage races. He’s carving out his own niche, which is very impressive. He’s stood by what he believes in and he’s completely old school. You could drop him into any generation from the last 100 years and he would have flourished. There are not many riders who you can say that about.

At the Olympics he was matching Bradley, pedal for pedal and it was terrifying what he was doing. I was exhausted, Froome was exhausted, yet Ian was still going. Bradley was the Tour winner and the best bike rider on the planet at that point and Ian hadn’t even done the Tour. That was one of the most impressive rides I had ever seen.

Domestique: Geraint Thomas (Great Britain)

Geraint’s race attitude has this blend of old school toughness and new-wave race craft. Like Cav, he radiates energy and you’re never going to have a bad day with him on the bike. Even when it’s going down the pan and you’re suffering like a dog, he’ll always find a way to pick you up. At the same time he has that dark edge which makes him competitive and ambitious.

I actually think that Stuey and G are quite similar. If G had come 15 years earlier he would have had that wild streak. There was also this moment when ONCE were looking at Stuey – back when almost anything seemed possible – and were thinking about turning him into a Grand Tour rider or the next Jalabert. Again, G is this controlled wildfire, because he will listen and do his job well but if it all falls apart then you can rely on him to save the day.

What stood out for me was Copenhagen Worlds in 2011. He was arguably given the hardest job of all, which was to lead out Cav. It meant that he had to ride 270 kilometers and then cool his cool and switch it on for just one minute.

Domestique: Iñigo Cuesta (Cofidis)

Almost the entire team is anglophile, while Iñigo would only ever speak Spanish. He had several years at Cofidis, and didn’t learn a word of French, and in his time at CSC he didn’t pick up any English but he didn’t care. He was a consummate pro, though, and a bit of a Christian Vande Velde, but without the same level of ambition.

In the 1990s when ONCE were at their peak if you go back and look at the results it was Alex Zulle or Laurent Jalabert at the top of the standings at the Spanish races but if you looked a few places down then you would always see Inigo’s name. He was always there and, while winning was never a motivating factor for him, he learnt how to become this incredible domestique.

Back in 2001, when I won stage 6 of the Vuelta, Iñigo was crucial. During our team meeting before the stage we had talked about our tactics and we both broke away near the finish. There were six of us in the group and I remember Inigo just gave me this look as we hit the final climb and I just knew he was going to work for me. You see, in races you have these different types of domestiques. You have your guys who can sit on the front for hours and you’ve got your ones who can lead out but then you have your finale domestiques, and that was very much Inigo’s type and style. He could read a race and he knew how to set it up for his leader. With most domestiques you need to ask them to work for you but if you were in a finale and Inigo was with you, you didn’t have to hesitate or ponder; he would give you that look and you would instantly know that he would work his socks off for you. At a team like Cofidis, where there was no structure, Iñigo was an invaluable teammate, along with Bingen Fernandez, who has only just missed out on being in my team.

Team director: Matt White

Matt was still racing with Discovery in 2007 and during the Classics, when the Sliptstream project was coming together, I thought that for some leftfield reason that we really needed Whitey as a DS. We met in a bar in Kortrijk, Belgium, and had a few beers. I told him he should join us as DS and really it just planted this seed in his head because I don’t think he quite knew in which direction he wanted to take things. I think it was one of the most inspired decisions I’ve ever made, approaching him like that, and I’ve never known a director like him.

As a rider he was your typical Australian pro, part of the foreign legion that would knuckle down and get the work done. No matter how bad the weather, he would be on the front with a smile and even though he wasn’t ever more than a decent domestique he liked that. He enjoyed the fact that he didn’t have huge responsibility and that if he did his work everyone would be happy with him. He was also a bit of a journeyman in many ways. He would travel to races with the Vini Caldirola mechanics and he would turn up at Grand Tours with just one carry-on suitcase of kit and clothing.

But, like so many on this team he just has this incredible energy, so you would leave a team meeting and it felt like you were in a Hollywood movie; he had everyone so ready and motivated. He has a kind side but he can also be a hard, even cruel bastard when he needs to be, but I guess that’s needed when you’re running a team. At his best, there’s no one close to him.