Cycling's most sensitive issue - Why saddle discomfort is one of the most pressing, and silent, barriers to entry for female cyclists

'Even amongst my fevered googlings late at night, I hadn’t come across anything that had explained the types of pain I might be facing'

A few years ago, I went to the doctor because I was convinced I had cancer.

Over a few weeks, a large, hard and painful lump had appeared in my groin. Initially, I dismissed it as an ingrown hair, but when wearing underwear became unbearable and sitting down too painful, I knew I couldn’t ignore it any longer. By the time I booked an appointment with my GP, the lump had grown to the size of a marble under the skin and was oozing a milky-white substance.

The doctor who saw me had a brusque manner. ‘That’s not a tumour,’ she said, snapping her gloves at her wrists after - in my view an unnecessarily short - rummage in my knickers, ‘it’s folliculitis. A bacterial infection of a hair follicle. It will go away in its own time if you keep it clean.’

I left the surgery red-faced and ashamed that I had wasted the doctor’s time, and slightly embarrassed about my panic. But the truth of it was that I was new to cycling and no one had ever warned me that increased miles on a manufacturer-issued saddle could result in something that looked and felt like a tumour. Even amongst my fevered googlings late at night, I hadn’t come across anything that had explained the types of pain I might be facing.

Since then, I’ve been acutely interested in women’s experiences of saddle soreness and discomfort, trying to better understand the landscape of our pain and figure out how and best to keep women on the bike. I’ll give you a bit of a spoiler: it’s all a bit complicated.

The scope of the problem

While we generally seem to refer to saddle sores in the cycling industry, it is more practical and accurate to talk about saddle soreness, which can manifest itself through a whole host of symptoms from your basic run-of-the-mill tingling, numbness, bruising, chafing, to slightly more serious ingrown hairs, boils and abscesses, labial swelling, vulval tears, folliculitis - as mentioned above - through to cystitis (a urinary tract infection) and thrush, the production of vaginal odor or even pain when going to the toilet (caused either by excessive pressure on the urethra or infections).

Research suggests that 60% of women suffer from saddle soreness (University of Colorado, 2014). My gut reaction is that this figure is to be likely even higher in reality, as it isn’t clear how many women are totally lost from cycling after experiencing saddle soreness and therefore don’t ever self report, nor does it take into consideration the women who for a myriad of reasons don’t - or can’t - ever admit to suffering.

I wanted to look a bit closer at this, so I conducted my own survey of 278 women, all of whom are active cyclists. I’ll talk more frankly about the results of this survey soon, but for me, one of the most gut-wrenching findings was that a significant proportion admitted they would never feel comfortable discussing their symptoms with anyone, not even with close friends, partners, or healthcare professionals.

This is a problem. A big problem. Not least because women are already extremely underserved by the cycling industry in the first place, and the reticence to discuss it further due to embarrassment, the fear of not being listened to, or the belief that women have a higher pain threshold and should ‘just get on with it’, compounds the issue further. The lack of discussion and research into these difficulties makes it harder for anyone to understand the problem, or to integrate women into the design process of products. As one unnamed male cyclist said to me, ‘I don’t even really know how much pain women are in, I don’t hear much about it’.

Whether the industry is not understanding women’s pain or just not listening remains to be seen, but we are starting to uncover that the long term impacts of continuous saddle soreness isn’t looking good. One study found that amongst competitive athletes, persistent compression caused by conventional saddles could lead to sexual dysfunction (Greenberg et al, 2019), while another study found that approximately half of the women they surveyed had experienced sexual discomfort and pain following long bike rides (Harrison, 2023). Heartbreakingly, I found this in my own survey, where some women disclosed that they choose between sex with their partners and riding their bikes.

What are women saying about their discomfort?

To better understand the realities of women’s experiences with saddle soreness and discomfort, I conducted a survey to gather real-life accounts. While I’ve spent years discussing these issues with my own friends, it was clear that my network, who are largely women of a similar age, fitness, and life stage to me, represented only a narrow slice of our cycling community.

The survey attracted responses from a diverse range of women from across the world, though most were aged between 26 and 45, had more than seven years of riding experience, and generally rode 21 to 50 miles a week. These are experienced cyclists, generally with more than 7 years of riding behind them, and nearly all of the 278 respondents reported suffering from saddle sores, often with multiple symptoms.

The stories they shared were, frankly, hard to read. Some described infected hair follicles developing into ‘grape-sized lumps’, with some requiring surgery. Others reported vulvar tears and labia swelling so severe that going to the loo for days after a long ride was painful, repeated instances of thrush or enlarged clitoris that became painfully sensitive. There were accounts of abscesses that burst, days spent unable to sit comfortably or wear normal clothes and underwear, and weeks off the bike to allow their bodies to heal.

Here are just a few of the experiences respondents shared:

- ‘I’ve had to quit events because I couldn’t sit on the saddle any longer and then couldn’t even pedal.’

- ‘I ended up with a large boil that was very painful, which meant I couldn’t ride. I had to take antibiotics to get rid of it.’

- ‘It became infected, and months later formed a cyst. The cyst capsule would fill with fluid on long rides for years and form into a hard lump. Eventually, I had the hair follicle removed by a plastic surgeon.’

- ‘During an ultra-endurance event, I developed small cuts around my labia. They became swollen and made it painful to pee. I had to scratch from the event.’

- ‘If it gets really bad, I’ll stop cycling for a couple of weeks. But now that I commute…I just have to push through, so it takes longer to heal properly.’

- 'I had a small split in my clitoris during an event'.

Many respondents expressed frustration at not knowing how to address these problems effectively. For some, the options are either to simply continue pushing through the pain to keep engaging in the sport they love or rely on for work or take extended breaks from cycling, never quite knowing if they’ll be able to return. These stories underline the urgent need for better understanding, support, and solutions for women facing saddle-related discomfort.

So what actually are the causes of so much pain?

Let’s go back to the beginning for a minute. There are undeniably certain anatomical differences in women that makes us much more susceptible to saddle sores than men, but research is still unclear as to actually how and why women suffer so much, or indeed whether they suffer to any more extent than men do, or whether men are just better catered to by the cycling industry. It’s all a bit messy, and while studies into men’s saddle soreness seem relatively advanced, the same can’t really be said about women.

When looking at women’s discomfort, it appears that there are quite specific patterns. Some women appear to have bleeding, pinching, tearing and swelling from excessive pressure, and others display more friction-like burns or tingling and numbness. The culprit for a lot of pain though, does seem to come from the vulva. A study by Harrison et al (2023) found 44% of women suffered with vulva or labia-specific pain.

The role of the vulva

If we’re going to get specific, and I think we should, we all need to get on board with the correct terms for the soft tissue ‘down below’. The correct terms are vulva, labia majora, labia minora and clitoris, and these refer to the bits that are most likely going to bear an unnecessary amount of weight when on a saddle and are usually the parts that become swollen, pinched, or bruised. The vulva is the collective term for the external visible genitalia that we see on women - we’re not using vagina here because that’s the internal passage that connects the uterus to the vulva. Labia majora and labia minora are the outer and inner ‘lips’ respectively, and the clitoris is the nub of flesh at the top of the vulva. You also might hear a bit about the perineum, which is the small triangle between the vulva and the anus, and this can also begin to get sore or bruised.

What makes saddle sores in women so much of a complex problem is the fact that there really isn’t a standard vulva - in fact, one study suggests there may be around nine different presentations of vulva, which makes designing a standardised saddle, bike, and components difficult for an industry that is looking to mass market the production of materials. Much of the research that currently exists into women’s pain is limited to the experience of competitive athletes. This is, of course, important work and imperative to ensuring parity in elite-level sport, but we know that athletes often use their bodies in very different ways to the average commuter. Understanding the role of the vulva and how the labia and clitoris might be supported by thoughtful product design is imperative to ensuring more women stay in cycling more broadly - which we desperately need.

The role of the cycling industry and women specific bikes

The mass market for bikes, in a lot of ways, makes things worse. It is perhaps unsurprising to most of you that the vast majority of bikes are not built for women, nor do many manufacturers seem to consider these differences in women’s anatomy during design. While there are some advancements in offerings such as those by Liv and Canyon, both of whom have developed specific women’s frames, research appears to be inconclusive about whether it’s a women’s specific geometry that is needed or just the availability and wider range of smaller frames.

On the one hand, we know that women are generally shorter in height than men, with smaller overall muscle mass, and often much more flexibility in the joints which may cause a woman to move differently on a bike. A shorter or lower top tube, a smaller wheel set allowing for a smaller frame, narrower handlebars, shorter cranks and a cut-out saddle - all of which appear on women’s specific bikes - should theoretically offer more comfortable rides for women. But, anecdotally, when I tried the Liv Devote last year, I found the cut-out saddle that came as standard horribly uncomfortable no matter how much I adjusted, and the narrower handlebars made riding much more unstable. ‘Women’s specific’ doesn’t necessarily mean that women will automatically find the bike more comfortable.

This is supported by a study Specialized produced following data from over 8,000 bike fits, which demonstrated that the differences between men and women are actually not as pronounced as originally thought, encouraging us to consider more carefully the range of needs of all riders rather than just through a gendered lens.

However, we’ve all seen the impact of the ‘just shrink it and pink it’ mentality in the industry, and though women-specific bikes might not totally fix the problem, they advocate for more inclusive design which certainly helps.

Will a saddle fix it?

In my survey, 68% of respondents identified that a poorly fitted saddle design was one of the root causes for their saddle soreness, with many reporting they’ve been unable to find a suitable saddle for their needs. On group rides of my own, I've witnessed at coffee stops women quickly swapping bikes to get a feel for different saddle fit. I spoke to Jenni Gwiazdowski, a saddle fitter and founder of London Bike Kitchen’s Saddle Library.

‘We need a better diversity of options on the market,’ Jenni says as we begin to discuss her work, ‘but we also need to be teaching women the tools of comfort and offering the space and time to help them navigate these choices.’ She adds that it’s also important women are given the opportunity to listen to their bodies to learn what is comfortable and what isn’t. Jenni sees herself as a ‘guide’ in helping people understand their ‘journeys’ with comfort: ‘because it really is a journey’, she says. ‘I can’t tell people what the right answer is, there isn’t one. There is no one perfect saddle for every person, because all our bodies are complex, different, and prone to change.’

Jenni highlights the complexity of saddle fitting, noting that comfort isn’t determined solely by anatomy or bike components. Factors such as riding style, fitness level, sweat composition, weather, chamois choice, muscle imbalances, or even life stages can play a role. For example, she points out that menopause-related changes, like the thinning of vulvovaginal skin due to decreased estrogen, can increase the risk of saddle discomfort.

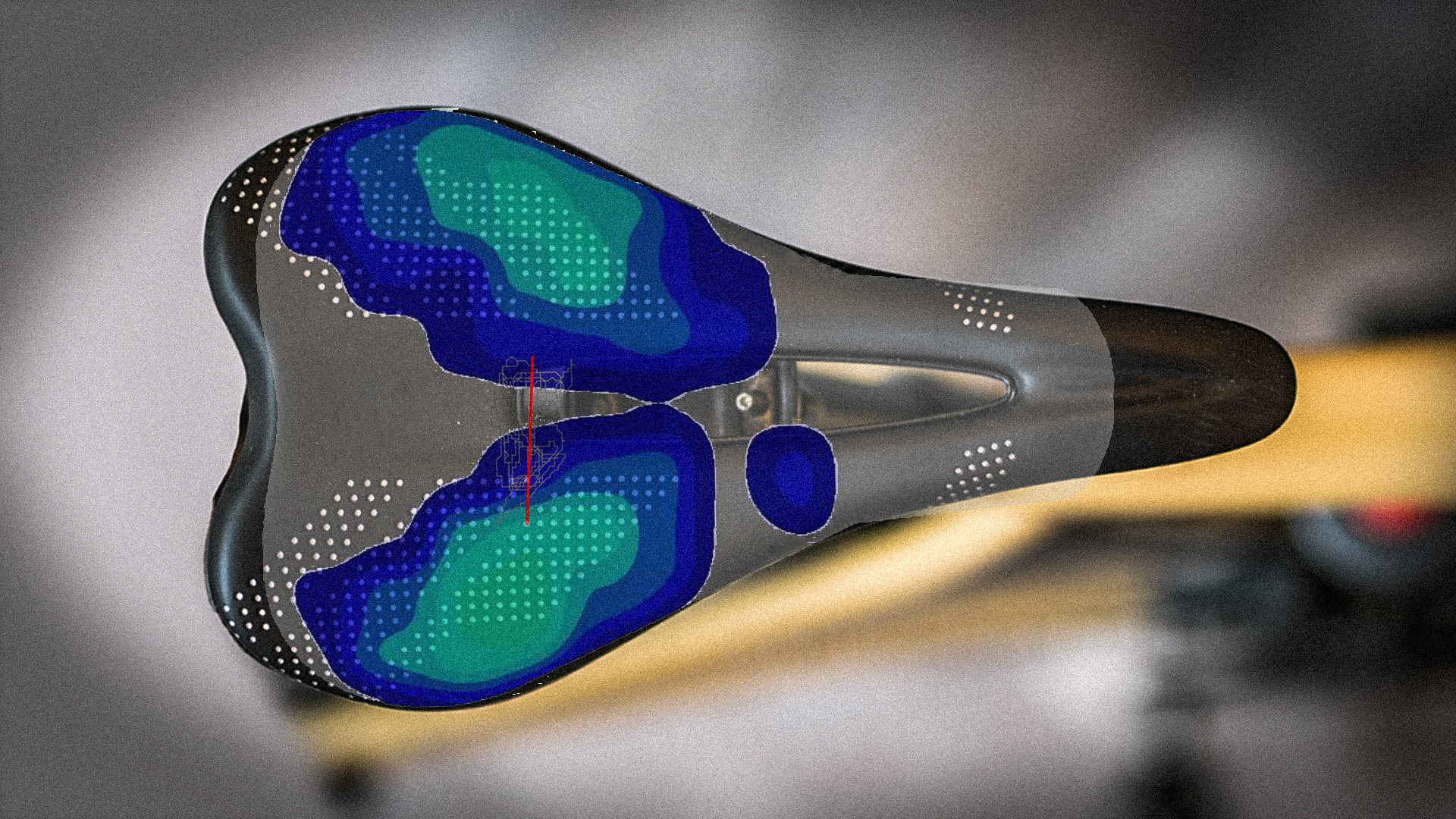

‘Historically we’ve always thought about sit bones when we’ve thought about saddles,’ she begins, ‘we would take the width and correlate the width of the seat bones with the width of the saddle but they won’t think about how the pelvis rotates and moves. Everyone’s pelvises rotate differently.’ This oversimplification may have limited the effectiveness of saddle design.

When it comes to saddle widths for instance, it’s always been thought that women generally have wider sit bones than men, however, research into external ischial tuberosity widths (the fancy science word for sit bone widths) studies present a much more nuanced perspective. Studies show that individual differences within each sex are much more significant than those found between male and female anatomies. This means that when we are talking about saddles specifically, it becomes less about ‘women's-specific saddles’ and more about a range of saddles offering different features for different needs - men, for instance, may just as easily find a ‘women’s specific’ saddle more comfortable than a man’s saddle’.

Jenni believes that manufacturers have spent a long time making products while only half understanding the needs of the individuals using them. I ask about the cut-out saddles we are increasingly seeing marketed as ‘women’s-specific’, skeptical of what seems a simple solution to an increasingly complex problem. ‘A lot of people get on with them,’ Jenni says, ‘and they’re certainly one solution.’ Cut-out saddles aim to reduce the compression of the labia minora and perineum by creating additional space and instead transferring weight to sit bones. They’re great for those who struggle with pressure on soft tissue but might not be as useful for individuals who struggle more with friction or burn-like saddle sores, once again reinforcing that just slapping the words ‘women’s-specific’ doesn’t necessarily solve the problem.

Ultimately though, women still aren’t seeing a bike fitter for support in finding comfort, and the ones that do aren’t always reporting that they were useful. ‘It’s expensive and I didn’t feel like I was listened to,’ one woman responded in my survey. A 2021 study suggests that it is unclear whether modern bike fitting protocols are entirely appropriate for both men and women due to differences in anatomical structures and a bias towards men’s cycling, though acknowledges there isn’t enough research to argue either way. Interestingly, a proportion of women in my survey voiced concerns that their cycling wasn’t ‘serious enough’ to justify the cost and time requirements of a bike fit, despite many of them stating that they believe the cause of their saddle sores was poor fitting bikes and saddles. I wonder if we’re acknowledging wider societal issues and the prevalence of self-limiting beliefs in the issue of saddle soreness enough.

How are people managing their saddle soreness?

In the small secrets shared quietly between women (and maybe this great article by Mildred Locke), there’s a rumbling debate between those who shave their pubic hair and those who do not, and those who wear underwear beneath their bib shorts and those who do not. You’re likely to be unsurprised when I tell you that there’s almost no research in favour of or against the efficacy of any of these things - we (again) unsurprisingly, just don’t know.

Most of the research we do have examines how women are already managing discomfort, as opposed to understanding the most effective options. My survey seems to align closely with a study completed by Bury et al, which showed that good quality padded shorts, applying chamois and barrier cream and a women’s specific saddle were the most helpful in reducing saddle soreness. In my study though, sadly, 22% selected that they ‘have not found anything to manage their saddle soreness’, while significant ‘time off the bike’ was also reported as the only method to reduce pain or discomfort. Both are a worrying statistic.

Bibs with an appropriate chamois have a lot to answer for when it comes to women’s comfort though. I asked Jenni Gwiazdowski whether a poor pair of padded shorts could negate any benefits gained in a saddle fit: ‘Absolutely,’ she says. This is reflected in the research, where Van den Stock et al found that wearing suitably padded shorts was almost as effective as changing saddle position.

However, it must be noted that not all bibs are built alike, and like the vulva, it’s impossible to find a standard pad to fit every body type. Personally, I know that a thicker pad in shorts or tights can lead to dryness and chafing of my vulva, while a pad too short in the front will cause bruising. Bagginess, or thickness at the back of a pad, will cause a kind of friction burn on my bum on longer rides, whereas ill-fitting shorts or tights can result in a combination. Jenni mentions to me that women will ‘often go for a thick, squishy pad’ in bibs, looking for that comfort against the jarring of the bike. ‘A squishy pad provides little support though,’ she says, ‘and so the body can move around a lot more and it can cause more problems in the long term’. It is, however, perhaps much easier for brands to market a squishy, thicker pad; they’re soft and logically it makes sense they’ll offer more comfort than something thin and structured, right?

So do we need to see more diversity in the market to allow for such different presentations of the body? ‘I still can’t find a pad that suits me,’ one of my survey respondents laments, ‘most brands look and feel the same. There’s no innovation happening.’

So what can we do about it? The Tl;DR

Speak to any woman in cycling and she’ll likely tell you the same thing as I am about to tell you - the cycling industry just isn’t offering enough diversity for women, or even probably for men.

Saddle soreness is incredibly complicated and incredibly personal, and I don’t think we’re anywhere near fully understanding the landscape of women’s pain, nor how best to manage it, and that’s a problem if we want women to continue cycling.

However, I fully endorse Jenni’s perspectives that we need to do better in supporting women to understand both their bodies and the options available to them, viewing comfort as an evolving journey rather than a final destination. We need:

- More research: More independent and peer reviewed studies attempting to understand the root causes of saddle soreness and the most effective solutions.

- Diversity: The prioritisation of women’s needs in product design as a standard as opposed to an afterthought. Product specs should be grounded in research and real-world feedback from women

- Better tools to navigate choice: Saddle libraries with experienced bike and saddle fitters could offer more routes to comfort, especially as product offerings expand.

- Opportunities to discuss: A more open, stigma free dialogue, with men contributing and listening too.

If you subscribe to Cyclingnews, you should sign up for our new subscriber-only newsletter. From exclusive interviews and tech galleries to race analysis and in-depth features, the Musette means you'll never miss out on member-exclusive content. Sign up now