Cycling's hypocritical and uneven handling of past dopers - Opinion

How do we choose who to 'forgive'?

Tom Simpson was not a pariah nor a witch, although if you didn't know much about his story, sometimes you might think so. Mention his name in anything other than condemnatory terms on social media over the past few days and you were guaranteed the righteous barbs of judgmental outrage on your head.

We all know the Simpson story, of death in the afternoon on the biggest, baddest mountain in France. Almost everyone believes he died solely because of doping, which is why when it came to marking the 50th anniversary of his death on Thursday, the Tour de France organisation opted to take its race out of sight and out of mind, to the western reaches of the Pyrenees, almost as far away from Mont Ventoux as possible.

This was too far for the Tour's media pack to travel, unlike in 2015 when Lance Armstrong passed within unsettling proximity of the Tour when he rode in the Day Ahead charity event with Geoff Thomas. As it turned out, the press room on the race itself was pretty empty that day because Armstrong, whatever you think of him, is still box office.

In the post-Festina, post-Puerto, post-Armstrong world, the Tour doesn't want any negative images, particularly any association with the ghouls of its shady past. The Tour's brand is going global, selling an image of cycling and its history that is highly selective.

I never knew Tom Simpson, so I don't know if he was a 'good' person, or a 'bad' person, but I do know that he died racing in the Tour. I know that he was a professional cyclist racing at a time when a culture of amphetamines was prevalent and I also know that, as a man, he was much loved and mourned.

Joanne Simpson, his daughter, recently tried to get at the definitive truth of his death, opening up legal proceedings to obtain his autopsy. "I can live with the truth," she told me. "If that's the truth, that Daddy took amphetamines, then so be it."

But Joanne will never know. The autopsy archive for records over 30 years old was destroyed in the late 1990's. She has a letter from the medical services in Avignon.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"French law authorises the destruction of medical records 25 years after death, or 30 years in some case. The dossier for Monsieur Thomas Simpson has thus been destroyed at some point between 1992 and 1997..."

None of the Simpson family other than Joanne had ever before requested the autopsy.

Anecdotally, everyone still living who was there that day, will tell you it is true — that amphetamines killed Tom Simpson, because they were found about his person and that he had a 'reputation' within the peloton.

But in researching my book 'Ventoux,' I began to understand that in fact it was more complicated — that dehydrated, sick for three days and racing in 42 degrees, he might have collapsed anyway, regardless of amphetamine use.

The more you learn about that Tour, the more apparent it is that he shouldn't have been racing anyway, because he was already too ill — just as Tony Martin shouldn't have been racing with concussion during this year's Tour, nor Jakob Fuglsang, who on Friday attempted to climb and descend in the Pyrenees when he was barely able to hold the handlebars.

In the end, ASO didn't really know what to do about the Simpson anniversary and fudged it. There was a photograph or two in the start village, a mention in passing on French TV coverage but no discussion of what Tom Simpson's death meant to the history of cycling or to the development of the notion that the riders weren't slaves or cannon fodder and that the sport itself had a duty of care.

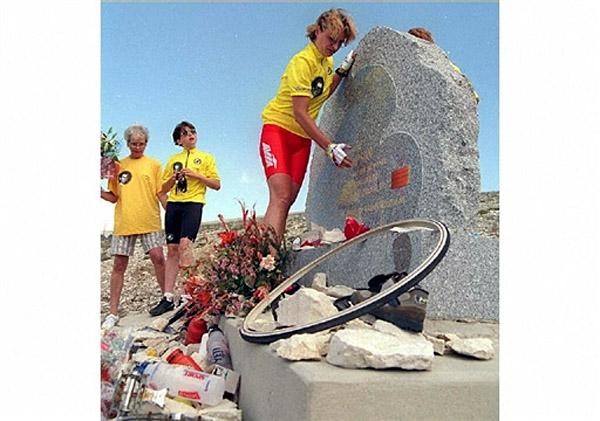

When I interviewed Joanne Simpson for my book 'Ventoux,' the scale of human tragedy of his death hit home. Joanne was four when her father died and cannot remember him. Bereft still, even after all this time, she regularly visits the spot where he died.

"Half the people who stop at the memorial don't even know that my dad ever won a race," she said. "They know that he died on the Ventoux – but they don't know that he won Flanders, or Paris–Nice or the World Championships.

"I sit there on the steps, and I hear what they say. Nobody knows who I am, but these people come up and you hear them say, "Oooh, look, this is where the alcoholic died" or, "This is where the doper died."

Simpson's name remains taboo, shameful, swept under the carpet. Meanwhile Richard Virenque, Alexander Vinokourov, Michael Rasmussen and David Millar — plus the many others who did but never confessed or got caught — stroll around the VIP enclosures at the Tour de France, untroubled.

If those ex-riders are allowed in the 'club,' then why is there a problem with Jan Ullrich or Lance Armstrong working on the Tour de France too? Personally, I wouldn't have a problem with that. But then that's because, while I hate the culture of doping and the human wreckage it leaves in its wake, I don't hate dopers per se.

Cycling has created a very tangled web, full of caveats and conditions on interpreting who can be allowed back, and who can't. Some it seems, we are willing to let back in, providing they say the right things, while others we are not.

So how do we choose who to 'forgive'? How do we distinguish between Ullrich and Armstrong, between Vinokourov and Virenque? Who is 'better' and who is 'worse'? Who makes those moral judgements or is it wholly subjective? For outsiders, looking in on this warped hierarchy, it can seem riven with hypocrisy.

And what, you might think as you watched Fuglsang wobble agonisingly up the Col de Latrape, of a duty of care, so lacking in 1967 and seemingly still, in its infancy? Are the riders still that expendable?

As they stood chatting by the Simpson monument in July 2013, journalist Peter Cossins, then of Procycling magazine, asked Greg LeMond for his interpretation of Simpson's death.

"This is not a sinister place at all," LeMond said of the Ventoux. "What is sinister is the lack of empathy for Tom Simpson as a human. And also the ability of the sport of cycling to brush off the deaths of others.

"It doesn't faze people in cycling," LeMond said. "That's the crime, that's the sinister part to me."