Doping excuses: 13 of the most brazen and bizarre

Sex, booze, and vanishing twins

There have been countless doping cases in cycling over the years, from the biggest names in the sport down to riders hanging on at the bottom of the food chain. As such, we've seen all manner of reactions to a positive test.

There are those who deny, deny, deny; the rare cases who speak out or co-operate; and then there are those who come up with interesting excuses for their abnormal results.

From the absurd and the implausible to the actually quite somewhat credible (though let's get real, usually absurd), there have been plenty such excuses through the years for us to pore over. We've done just that, trawling through the archives to take a look at 13 notable cases from cycling history.

Twin's blood – Tyler Hamilton, 2004

We'll start off with one of the more infamous excuses – that of Phonak rider Tyler Hamilton, who tested positive for a homologous blood transfusion at the Vuelta a España on September 11, 2004.

Hamilton also returned an A-sample positive on August 25, 2004, after winning time trial gold at the Athens Olympic Games, but was not sanctioned for that as his B-sample was effectively destroyed by the Athens lab that did the testing, and no result could be determined from the sample.

Hamilton's Vuelta samples showed signs of a mixed red blood cell (RBC) population. The American's defence rested on claims that he had a 'vanishing twin', who had transferred some of its RBCs to Hamilton while he was in the womb, but disappeared in the first trimester of pregnancy; or that he is a human chimera, with a natural mixed RBC population.

Hamilton was banned until September 22, 2006, and then returned to the road with Rock Racing before failing an out-of-competition drug test for an anti-depressant. He announced his retirement soon afterwards. In 2011, he admitted to doping, and returned his Olympic gold medal.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Since retiring, Hamilton has taken up coaching, and in 2012 co-authored The Secret Race, a tell-all story of his career, including his time at US Postal and the doping programme run by the team.

They're for my mother-in-law – Raimondas Rumšas, 2002

In 2002, 30-year-old Raimondas Rumšas was in the midst of his third year as a professional, racing to a surprising third overall at his first-ever Tour de France participation. Upon finishing the race in Paris, though, things immediately fell to pieces for the Lithuanian.

On the very same day he stood on the podium alongside Lance Armstrong – later disqualified from victory due to doping – and runner-up Joseba Beloki, French customs officials in Chamonix discovered EPO, testosterone, growth hormone and anabolic and corticosteroids in his wife Edita Rumšienė's car.

When questioned about the drugs, Rumšas claimed: "I have not had a chance to speak with my wife. But the products were intended to be taken to Lithuania for my mother-in-law, Yakstenia."

Rumšas was later banned for testing positive for EPO at the 2003 Giro d'Italia and, together with his wife, received a four-month suspended sentence for importing prohibited drugs into France.

Rumšas' son, Raimondas Rumšas Jr, tested positive for GHRP-6 in late 2017, months after tragedy struck the family when youngest son Linas died of a heart attack at the age of 21.

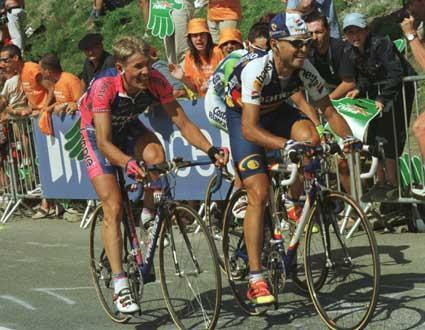

Blood on the legs – Alexandre Vinokourov, 2007

Current Astana team manager Alexandre Vinokourov came up with a bizarre excuse when testing showed he had two distinct red blood cell types at the 2007 Tour de France – similar to Hamilton's case.

A yellow jersey favourite before the race, the Kazakhstani crashed heavily on stage 5, suffering widespread wounds to his knees and elbows. Vinokourov, who admitted links with Dr Michele Ferrari earlier in the month, fought back against his injuries later on, winning a ludicrous time trial on stage 13, 1:14 ahead of Cadel Evans, and then soloing to victory on stage 15 in the Pyrenees after leading a bridging move up to the break.

The good times didn't last, though, with the next day in Pau bringing news that a test carried out after the time trial had found evidence of a blood transfusion. The Astana team, which featured the equally questionable Andrei Kashechkin (who later tested positive for the same method) in fifth overall, immediately left the race.

And the excuse? "I think it's a mistake, in part due to my crash," Vinokourov said. "I have spoken to the team doctors who had a hypothesis that there was an enormous amount of blood in my thighs, which could have led to my positive test.

"The setting-up of our team made a lot of people jealous and now we're paying the price. It's a shame to leave the Tour this way, but I don't want to waste time in proving my innocence."

Vinokourov returned to racing in 2009, winning Liège-Bastogne-Liège and a Tour stage in 2010, plus the London Olympics road race in 2012, before retiring at the end of the year.

Opium cakes – Alexi Grewal, 1992

The 1984 US Olympic road race gold medallist said he tested positive for opiates after gorging on poppy-seed muffins before the prologue at the Tour of West Virginia in 1992.

While opiates have no performance-enhancing qualities, they are banned to prevent their use in helping athletes compete while injured.

"I obviously won't be eating poppy-seed muffins in the near future," Grewal said afterwards.

The U.S. Professional Racing Organisation issued a three-month suspended sentence and a $500 fine. In 2008, Grewal admitted to doping several more times during his career.

Where's the beef? – Alberto Contador, 2010

One of the more complicated sagas on this list, Alberto Contador's clenbuterol positive at the 2010 Tour de France still elicits debate today. The Spaniard had initially won the race, finishing 1:39 up on Andy Schleck, but in September he announced that he had tested positive for trace amounts of the drug.

Contador blamed food contamination, allegedly eating contaminated meat on July 20 and 21. The amount of clenbuterol present in his positive sample was 40 times lower than the detection level required of World Anti-Doping Authority (WADA)-accredited laboratories.

Another wrinkle saw Contador informed of the test in August, with the news only coming to light a month later after German journalist Hajo Seppelt started investigating the situation. Contador later claimed that the UCI wanted him to keep it quiet.

The lack of positive clenbuterol samples among livestock tested in Spain in 2008 and 2009 threw the Spaniard's claim into doubt. A theory that the trace amounts came via blood transfusion also emerged, with Spanish doctor Jordi Segura commenting that Contador's test reportedly returned elevated samples of plasticisers, which would point towards a transfusion.

WADA rejected Contador's claims of contamination, and, in January 2010, the Spanish Cycling Federation's disciplinary commission recommended a year-long ban. The following month, he was cleared by the Federation, and in March both the UCI and WADA took the case to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS).

Contador went on to win the 2011 Giro and finish fifth at the 2011 Tour, as the CAS case was delayed time and again. The hearing finally began in November, and he was handed down a two-year ban, retroactive from the 2010 Tour, in February 2012.

It was quite an ordeal, and you can follow the entire timeline here.

Contador returned to racing later in 2012, winning a thrilling edition of the Vuelta a España before going on to win another in 2014 and the Giro in 2015, before retiring in 2017.

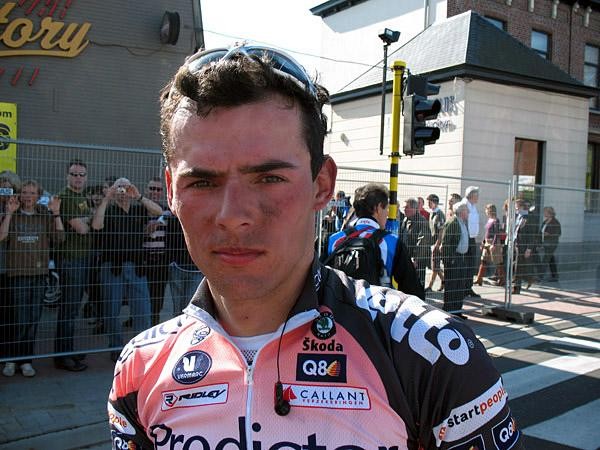

Throes of passion – Björn Leukemans, 2007

In September 2007, Belgian rider Björn Leukemans, then riding for Predictor-Lotto, was found to have a testosterone to epitestosterone ratio above the threshold of 4:1. Leukemans quickly brought up his natural high testosterone levels, which saw him encounter problems in 2001 and 2006 before things were straightened out.

Leukemans pivoted to another excuse soon after, arguing that he was having sex with his wife when the testers turned up at his house. The claim was swiftly dismissed by the head of the Cologne doping lab, who said "sex has nothing to do with [the] synthetic testosterone" which was found by the test.

In December, Leukemans claimed that a team doctor had prescribed him Prasteron, which contains the steroid DHEA. He was banned for two years in January 2008, later reduced to six months, and returned to racing with Vacansoleil at the end of the year.

A further twist came in 2012, however, when the Flemish Sports Council's disciplinary committee retroactively cleared him altogether.

"It is a great load off my mind," said Leukemans at the time. "It was a hassle in previous years, but now I'm totally cleared."

Candy – Gilberto Simoni, 2002

Reigning Giro d'Italia champion Simoni endured a return to forget in 2002 when it was revealed on stage 11 – with the Italian lying third overall – that he had tested non-negative for cocaine on April 24.

The Saeco leader left the race that day after police turned up at the team hotel to question him. He quickly brought up a visit to the dentist on the same day of the test, where he had been administered an anaesthetic containing carbocaine.

Nevertheless, his race was over, with the Giro already reeling after 2000 winner Stefano Garzelli, who won two stages and held the pink jersey in the first week, had tested non-negative for a masking agent.

Later on, another non-negative test for Simoni arose, dating to the middle of the Giro. The second case came as a result of the Italian consuming Peruvian sweets given to him by an aunt. He was cleared of both cases by the Italian Cycling Federation's disciplinary committee and went on to return to – and win – the Giro in 2002.

Drinking is manly – Floyd Landis, 2006

Floyd Landis' positive test for testosterone at the 2006 Tour de France and the ensuing saga, which lasted four years before his admission, and would later end up taking down Lance Armstrong, is surely the most well-known case on this list.

Landis had a bad day on July 19, 2006. While riding the Tour's 16th stage from Bourg d'Oisans to La Toussuire, he lost the yellow jersey, and with it a mammoth eight minutes. He then went back to his hotel and downed two draft beers and "at least four shots" of Jack Daniel's whiskey.

The ratio of testosterone to epitestosterone in his urine sample taken the next day when Landis made a miraculous recovery was said to be 11:1 – some way above the acceptable threshold of 4:1.

Some studies showed that alcohol can raise testosterone levels up to 200 per cent, although no amount of alcohol consumption would explain the presence of synthetic testosterone, detected via the Isotope Ratio Mass Spectometry method.

The case was – almost – finally settled in September 2007, when the US Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) sentenced him to a back-dated two-year ban, stripping him of the Tour title. An appeal to the CAS followed, but was lost. A further appeal against the CAS decision in US federal court came to an end in late 2008, as Landis settled with USADA.

Landis admitted to doping in May 2010, later turning whistleblower against Armstrong and US Postal before founding a CBD company, Floyd's of Leadville, and

later investing his own funds into sponsoring a Continental cycling team, which folded in 2019.

Fertility problems – Mauro Santambrogio, 2014

Mauro Santambrogio endured a mixed time during his time at BMC between 2010 and 2012, with high points including top 10s at Il Lombardia, the GP Ouest France and the Clásica San Sebastián, interspersed with two team-enforced 'deactivations' as he and teammate Alessandro Ballan were subject of the Mantova doping investigation.

A move to the neon hues of Vini Fantini-Selle Italia followed for 2013, with a fourth place at Il Lombardia at the end of 2012 hinting at what was to come. The highlight of the 28-year-old's spring with his new team included a win at the GP Larciano, second at the Giro del Trentino and seventh at Tirreno-Adriatico.

His mid-career surge continued at the Giro, where he formed a solid partnership with Danilo Di Luca. The pair took eight top 10s during the first half of the race, with Santambrogio riding into the top 10 overall. His big moment came in terrible weather on Bardonecchia, where he emerged from the mist alongside Vincenzo Nibali to – unbelievably – take victory on the summit finish.

It was all false, though, of course. Di Luca's EPO positive in April came to light two days before the end of the race, while a week after the finish and Santambrogio's ninth place, it was announced that he had tested positive for EPO on stage 1.

A two-year ban (later reduced to 18 months due to co-operation) and mental struggles followed, but Santambrogio was set to return with Amore & Vita in 2015. The comeback was cancelled, though, after a positive test for testosterone in October 2014.

Despite his protestations – he claimed to Cyclingnews that he had taken a course of drugs for erectile dysfunction and infertility, and had informed the UCI – he was banned for three years. In late 2019, he was banned for three months after attempting to take part in a fixed-gear criterium after declaring that he had never been sanctioned for doping.

Pigeon pie - Adrie van der Poel, 1983

Some folks like water, some folks like wine, but in 1983 the future Liège and Flanders winner Adrie van der Poel tested positive for strychnine.

The Dutchman, then in his third year of racing at the top level, was either way behind the times and using the toxic substance popular as a performance enhancer during the turn of the century, or had ingested it by accident.

As it happens, it turned out to be the latter. Van der Poel's father-in-law was a pigeon racer and served the then 23-year-old a portion of doped-pigeon pie.

Van der Poel went on to enjoy a top career, winning a wealth of Classics, two Tour stages, and the Cyclo-Cross World Championships. Nowadays, he's perhaps best known as the father of multi-disciplinary phenomenon Mathieu.

Java high – Gianni Bugno, 1994

Two-time world champion and 1990 Giro winner Gianni Bugno was banned for two years in August 1994 following a positive test for caffeine at the Coppa Agostoni.

Bugno denied taking any drugs, despite his sample being 30 times over the prohibited limit. He instead blamed a cup of coffee he had drunk before the race.

The reasoning was, of course, absurd. He won an appeal, though, serving a reduced sentence and returning to racing the next season.

Today, caffeine is on the World Anti-Doping Authority's monitoring list, and its use does not carry a ban. Bugno, meanwhile, flies RAI television helicopters at the Giro d'Italia and serves as President of the Association of Professional Cyclists (CPA).

Haemorrhoids – Jesús Rosendo, 2010

The Spaniard, riding for Andalucía-Caja Granada at the time, was among the early waves of cases started on the basis of suspicious biological passport readings. The method, which collates various biological markers of doping to establish a natural baseline, came into use in the late 2000s.

Rosendo was named alongside the higher-profile duo of Franco Pellizotti and Tadej Valjavec in May 2010, and was the second Andalucía rider in a month to 'catch a case', after Manuel Vasquez Hueso's EPO positive.

Both Pellizotti and Valjavec were eventually suspended for two years following appeals to the CAS. Rosendo, on the other hand, took a different route, with his team suggesting that his one abnormal reading – low haemoglobin and haematocrit levels along with increased reticulocytes – came as a result of anaemia due to bleeding from haemorrhoids.

Rosendo was not sanctioned, and raced on for three more years. The biological passport, meanwhile, has continued to snag riders every now and then. Denis Menchov was suspended after retiring in 2013, while Juan José Cobo was banned in late 2019, five years after the end of his career.

Binge drinking – Jonathan Tiernan-Locke, 2013

British rider Jonathan Tiernan-Locke looked like the next big thing in 2012. The 27-year-old was riding for Continental squad Endura Racing at the time, his fourth year at that level having struggled with Epstein-Barr virus a few years earlier.

The Devonian made a breakthrough with Rapha at the end of 2011, with second at the Vuelta a León and fifth at the Tour of Britain. His career really took off in early 2012, though.

In February he beat a host of WorldTour riders to the Tour Méditerranéen title by 27 seconds, then won the Tour du Haut Var a week later before beating the likes of Wout Poels, Samuel Sánchez and Robert Gesink to take second at the Vuelta a Murcia.

June saw him dominate the Tour d'Alsace, winning two stages and all three jerseys on offer. A return to the Tour of Britain saw him become the first Brit to win since the 1993 Milk Race, taking second on the queen stage to Caerphilly.

All of that earned him a place at the Limburg Worlds, where he rode well to take 19th place, the top British rider. A contract with Team Sky followed, but the results didn't continue, with illness and plenty of DNFs making it a lost season.

Things got worse for him in September, as he withdrew from the Worlds after receiving a UCI letter questioning his blood values dating back to September 2012. With Endura not part of the Biological Passport programme, he was only monitored following his Tour of Britain victory.

The governing body opened a bio passport case in December, and after a delayed hearing, he was banned for two years in May 2014. His defence – that bingeing on two bottles of wine, as well as gin and vodka just three days before the 2013 Worlds caused dehydration and abnormal blood values – was roundly rejected by the UK Anti-Doping panel, who stated that use of blood doping or an erythropoiesis-stimulating agent was the cause.

"It is inconceivable that a professional rider, selected for the first time to ride for his country at a senior level in the World Championships, would not have ensured that he was fit to race and had ensured that he had taken on sufficient water to deal with any hangover which he was still experiencing," their written verdict said.

Tiernan-Locke made a brief return to the British scene in 2016 with his own team, Saint Piran, before retiring the next year.

Dani Ostanek is Senior News Writer at Cyclingnews, having joined in 2017 as a freelance contributor and later being hired full-time. Before joining the team, she had written for numerous major publications in the cycling world, including CyclingWeekly and Rouleur. She writes and edits at Cyclingnews as well as running newsletter, social media, and how to watch campaigns.

Dani has reported from the world's top races, including the Tour de France, Road World Championships, and the spring Classics. She has interviewed many of the sport's biggest stars, including Mathieu van der Poel, Demi Vollering, and Remco Evenepoel, and her favourite races are the Giro d'Italia, Strade Bianche and Paris-Roubaix.

Season highlights from 2024 include reporting from Paris-Roubaix – 'Unless I'm in an ambulance, I'm finishing this race' – Cyrus Monk, the last man home at Paris-Roubaix – and the Tour de France – 'Disbelief', gratitude, and family – Mark Cavendish celebrates a record-breaking Tour de France sprint win.