Cycling: A second chance for Rwanda

15 years after the Rwandan genocide, the Tour of Rwanda showed the world just how far the country's come. Procycling travelled there to see how cycling is giving so many a new lease of life

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

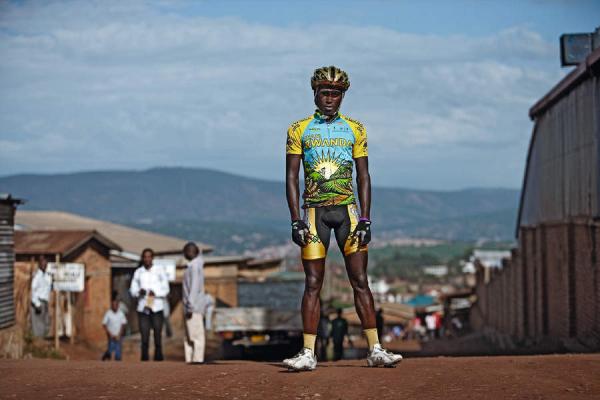

In the morning of the 19 November, Obed Ruvogera's expression registered only a hint of resignation as he was caught and then passed by the peloton. Yet just five minutes before that moment, he'd been riding out on his own at the front of his national tour, midway through the fourth stage that ran between Kibuye and Butare.

His attack failed due, in part, to a minor mechanical fault, his troubles beginning when he felt his right pedal coming loose on a descent. A basic Allen key could have fixed the problem but the neutral service car had neither the right tool nor a qualified mechanic on board. That led to Ruvogera being caught – first by a counter-attack and then by the peloton. Displaying disarming patience, he simply waited for his team to come and rescue him.

Even without the fault, a stage win was hardly a certainty for Ruvogera. The Moroccan national team, whose lack of results in recent months hadn't escaped their king's disgruntled attention, swept all before them in Rwanda. In the end, they took six stage wins out of eight and held five of the top six GC spots. What Ruvogera demonstrated, however, was the panache of the Rwandan riders, sending thousands of roadside fans into raptures.

Team Rwanda hardly skimped on effort in their home tour, though. They were better than their rivals on the climbs dotted throughout the course but were frequently caught out in the flatter stage finishes. That climbing prowess says a lot about the Rwandan team too, since the altitude gain in stages between 124-163km long could be as much as 2,600m. With a little more experience, they could soon be a force to contend with. Their performance was also indicative of a nationwide aim – to truly emerge on the world stage and shake off the the prevailing perceptions created by the country's chequered past.

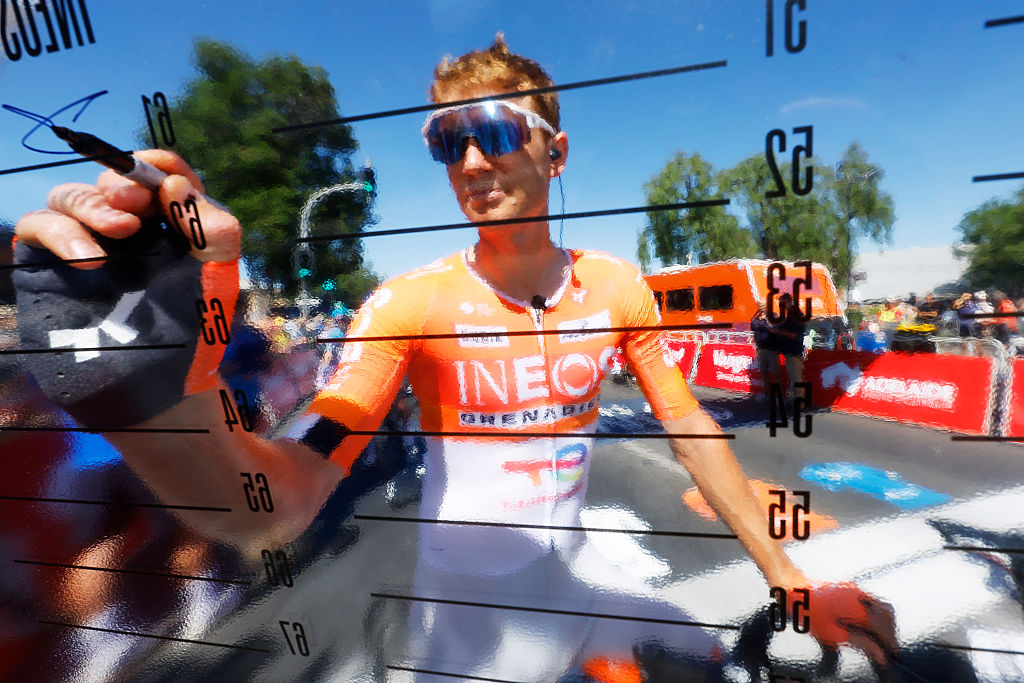

Almost as much anticipation and hope as the team had to bear was riding on the reception of the event itself. Given that it was the event's first year on the UCI calendar, the Tour's organisers set out to make a faultless impression. And for the most part, they succeeded.

For example, the president of the jury, Colin Crews, issued a reminder of the UCI's rules before the first stage, stating that, "Any rider who hangs onto cars will be disqualified." His reminder was heeded and the Tour of Rwanda was refreshingly unmarred by any incidents of real cheating.

However, some minor rules were simply impossible to enforce, such as the requirement for all of the riders from any one team to wear the same jersey every day. The Kenyans, for instance, initially tried racing in football kits, before the organiser of the Ariégeoise cyclosportive stepped in to lend them jerseys.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The event was also an unqualified success with Rwandans, taking only a few days to embed itself in the public consciousness in its new UCI form. To begin with, during the first few stages, the crowds watched impassively, almost without a sound. Applause was rare. After a week, they'd become delirious – transistor radios pressed to their ears and hailing their heroes ecstatically. No doubt this transformation was aided by the event's timely slot in the middle of the holidays and the blanket radio coverage it enjoyed.

The Europeans in attendance quickly succumbed to the spell of the race too, which had the same feel as early editions of the Tour de France. The riders faced dirt roads often armed only with bravery and bikes 25 years behind the times, and weighing 17kg in the Burundi team's case.

The organisers' only major disappointment was being unable to persuade Lance Armstrong to take part. "He could have talked about the war on cancer," rued Aimable Bayingana, president of the Rwandan cycling federation. "In reality, we wanted to show what our country is capable of through this event. The Tour of Rwanda has to become, very quickly, the most famous race in Africa."

It seems Rwanda is beginning to take stock of cycling's potential as a publicity vehicle too. As Joseph Habineza, the minister for sports and culture, explained, "With the Tour of Rwanda, we wanted to show other countries that we stand for peace and that we're a very safe country, not just a place that people associate with gorillas and genocide."

A bold aim because, of course, people tend to associate two things with Rwanda – the work of Dian Fossey and the 1994 genocide. The Tour of Rwanda, however, showed that the Republic is now in position to start changing that view.

Yet despite Rwanda's efforts to distance itself from its troubled past, it's clear its wounds have not yet healed. The signs are everywhere. For example, just as ProTour riders sometimes wear bracelets to show their support for the crusade against doping, you'll see Rwandan riders wearing wristbands that carry the inscription, 'Genocide: never again'. similarly, the best young rider in the race wore a white jersey sponsored by the National Commission for the Campaign Against Genocide.

The stages themselves are also haunted by past horrors. The stadium in Kibuye, which played host to stage 3, is being demolished, since more than 4,500 Tutsis were killed there on 17 April 1994. likewise, stage 6 – a time trial in Kicukiro, a district of the capital, Kigali – seemed to finish in the middle of nowhere, except that on 11 April 1994, nearly 5,000 people died a few metres away. The stage was dedicated to the genocide's victims.

"We try not to think too much about what happened but it's difficult," admits Adrien Niyonshuti, who wore the best young rider's white jersey at the tour.

For their part, Team Rwanda's management "tries not to dwell too long on the past when talking to the riders". Not that it stops their riders visiting orphanages to explain how cycling provides them with a respite from their grief and hardship.

That sense of salvation in cycling runs deep within the team and most have experienced some form of real tragedy. Obed Ruvogera, the ill-fated breakaway star of stage four, is of Tutsi origin. His family belonged to the native group that 1994's Hutu leaders came to regard as the enemy from within and, in their odious terms, cancrelats or cockroaches that needed eliminating. Obed was just 14 years old. He lost three brothers and two uncles.

Nathan Byukusenge is the same age as Ruvogera and he lost his father. "We had one night to escape," he recalls. "My parents and my brothers all hid. I spent time in the mountains, in the rain. sometimes, kind-spirited locals fed me. I pleaded with them, 'Don't report me, they kill us like animals.' They'd then try to get rid of me quickly, so as not to make enemies.

"There were lots of us, hiding away in the mountains. When the soldiers told their spokesman that the war was over and we could go home, lots of us thought it was a trap and stayed in the forest. some people just disappeared. I gambled and went down towards the soldiers. life in the mountains was so difficult that I was ready to die. In the end, the soldiers were right. I went back home and waited a month for my sisters, brothers and my mother to come back."

Like 85,000 other young Rwandans, Byukusenge became the family's father figure at the beginning of his teens. He started juggling part-time jobs, initially as a hairdresser, then as a bike chauffeur. The latter would reveal his talent and lead to him riding professionally for MTN, a south African Continental division team sponsored by a telecom company, in 2009.

Team Rwanda's Rafiki Uwimana doesn't recall quite as many details but he was just six years old when the genocide happened.

"To escape it, my parents had sent me to my grandmother's in the countryside," he says. "In the months that followed, Rwanda was destroyed and people went crazy. I had to wait more than five years to go back to my parents' place."

For five years, his mother and father thought he was dead, "But then I thought they were dead as well," he says. And after every race, Uwimana cycles to visit the 99-year-old grandmother who raised him in that troubled time.

It's not just the Rwandan nationals who are experiencing the life-changing upsurge of cycling in the country either. Tom Ritchey, the co-inventor of mountain bikes in the '80s and the owner of us-based Ritchey Design, fell in love with the country on a visit there in December 2005.

At that time, he was the guest of a friend, Peb Jackson, who was in turn travelling with Rick Warren, the author of a Christian book called The Purpose Driven Life. The president of Rwanda, Paul Kagame, had devoured the book and invited Warren to the country as a sign of his admiration.

"I was going through a hard time," Ritchey admits. He, like Kagame, drew strength from Warren's book. However, he says his real saviours were a bike and the spirit of adventure he found in Rwanda.

"The first time that I went out on my bike, a Rwandan followed me with a big sack of potatoes loaded onto his bike. He was smiling behind my back. I realised then how many people here used bikes, in particular wooden bikes, to transport fruit and vegetables. so in the autumn of 2006, I created a race – the Wooden Bike Classic. The Rwandans soon confirmed that they had great potential as cyclists."

The wooden bike virtuosos would become Team Rwanda's first riders. Ritchey called an old friend, Jonathan 'Jock' Boyer, in to lend a hand with the fledgling team. Boyer has become more than just the directeur sportif or coach of Team Rwanda. Once a week, the national team's riders spend a day in his house in Ruhengeri, a tourist destination close to a volcano and a forest populated by gorillas.

"It's so they can get a warm shower, balanced meals, train together and look at the internet," he explains. some of the southern Rwandan riders take two days to cycle there. Their gratitude is boundless. "I've called my son Jonathan, in homage to Jock," says Uwimana. Boyer has kept his house in Monterey, California, and his ranch in Wyoming. But while he could quite easily run a business or a professional team, he's devoted himself to turning Rwanda into Africa's premier nation of cyclists through Project Rwanda.

Thanks to the project, the riders receive a monthly allowance of $100, which doubles when you add prize money. To put that in context, the prices at a supermarket in Butare drive home the exorbitant costs most Rwandans face – a kilogram of Italian pasta costs $4.80 (almost 10 times the price of rice), muesli made in Kenya is $11.40 and the same tariff is charged for chicken, the least expensive meat on offer.

The centre in Ruhengeri has helped the men of Team Rwanda become even more than pro cyclists. Project Rwanda has also paid for some of them to obtain their drivers' licences and learn English. It's even enabled a few to buy a TV set, which allows them to turn a front room into a makeshift cinema and charge for admittance.

The team's approach seems to be working – at the end of 2009, Rwanda boasted around 60 registered riders, seven clubs and four national competitions. Those numbers are set to increase over the coming years. "I hope to test 300 new riders in 2010," says Boyer.

Every week, riders come to his home for trials. At the moment, the best riders can cover around 20,000km a year, produce 4.7 watts per kilogram, score around 71 in VO2 Max tests and have a natural haematocrit of up to 49. "If we do the Tour de l'Avenir next year, we could place a rider in the top 15," says Boyer.

If the team do make l'Avenir, it will follow on from their first tilt at the Giro delle Regioni in Italy, which is set to be the team's first ever European outing. Despite their inexperience, Boyer has no doubts about their abilities – alongside riders from other countries, he believes the Rwandans could well form the backbone of the first ever African team to ride the Tour de France. should they achieve their goal of a 2015 Tour start, would it not be the Tour itself that would find itself reborn?

Regardless of whether the team achieve that goal, it's clear that cycling in Rwanda is changing lives for the better. To some, it offers redemption. To many others, it's a chance for a better life.