Cold comfort: Hampsten's day on the Gavia

You know those cheesy motivational posters that picture extreme situations captioned by...

An interview with Andy Hampsten, May 29, 2008

It was the greatest victory of his career, but what Andy Hampsten had to endure on the Passo Gavia in order to secure the 1988 Giro d'Italia, no man would envy. As the racers in this year's Giro prepare to tackle this beast of a climb, Procycling's Jason Sumner asked the USA's only winner of the Corsa Rosa to re-live that day.

You know those cheesy motivational posters that picture extreme situations captioned by inspirational slogans such as "Perseverance", "Teamwork" or "Integrity"? Well, there ought to be such a poster from stage 14 of the 1988 Giro d'Italia that reads simply "Guts".

If you follow cycling with even a casual eye, you've probably already seen the perfect image for the poster. It's a slightly blurred photo of Andy Hampsten nearing the top of Italy's famous Passo Gavia. His head and shoulders are covered in snow, his legs bare and pinkish, revealing the effects of the bitter chill. Cars sit just off Hampsten's back wheel, and it's not hard to imagine the American coming to his senses, tossing aside his bike, and jumping into one of those cars.

Of course that's not what happened. Instead, the waif-like climber from the American-based 7-Eleven team ploughed on, cresting the top of the 2621m summit, then surviving the bone-chilling 25km descent on the other side. This truly heroic effort was good enough for second place on the stage behind Dutchman Erik Breukink, and it pushed Hampsten to the top of the overall standings, a position he never relinquished on his way to becoming the first non-European (and still the only American) to win the Italian grand tour.

This year, the Gavia is back in the race route, serving as the opening salvo on stage 20 – a brutal, 224km run that also includes ascents of the Mortirolo and to Aprica. No doubt this will be a hard day and may also decide the race, but it's unlikely that the 2008 edition will inflict the pain Mother Nature unleashed on the peloton 20 years ago. Only those who were there truly know the extent of the suffering, and few know it better than Hampsten.

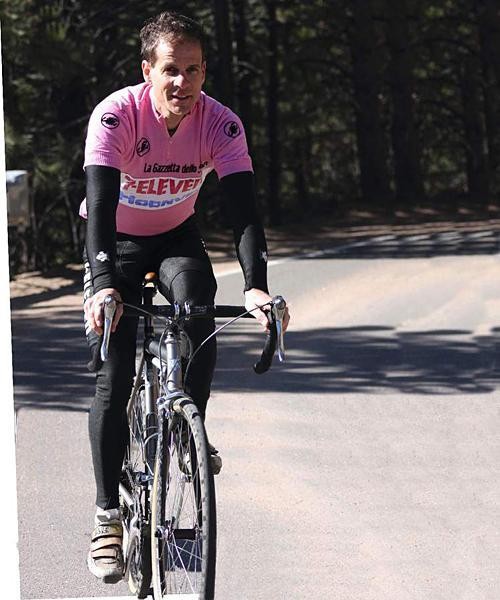

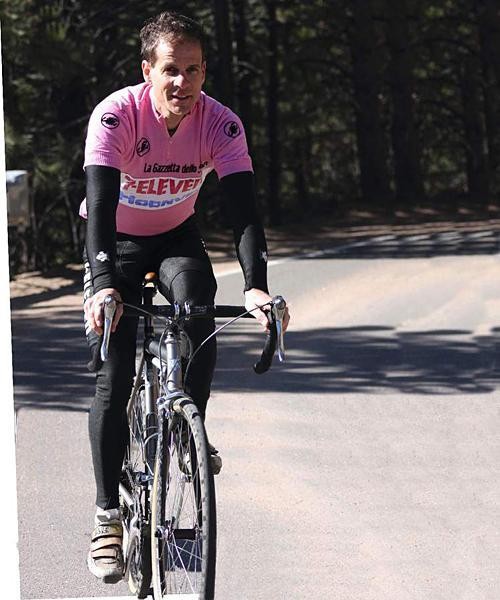

In March, Procycling sat down with the man in the famous photo. Hampsten is now a 45-year-old father of one who prefers snowboarding to bike riding on wintry days. But when the weather is good, his lean, fit frame is a dead giveaway that he still gets out on the bike two or three times a week.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Hampsten splits time between the comfortable confines of his log-cabin house in Boulder, Colorado, and Italy's Tuscan countryside, which is base of operations for his Cinghiale Cycling Tours company. Indeed, ever since the Ohio native made his European racing debut at the 1985 Giro, Italy has occupied a precious place in his heart.

That race is where we begin, as the legendary Andy Hampsten gives us a privileged peek inside one of cycling's most select clubs: The Men Who Survived That Day On The Gavia.

Procycling: Obviously the 1988 Giro d'Italia is where you gained your greatest fame, but from a personal point of view, wasn't the 1985 race at least equally significant?

Andy Hampsten: For sure. Winning stage 20 there will always be one of my favourite race-winning moments. It was the point in my career when I realised I could actually do this.

Procycling: So set it up for us. Your 7-Eleven team-mate, Ron Kiefel, had already won a stage, and then it was your turn...

AH: Yeah, you can't downplay what Kiefel did. His win kicked down the door for all of us. He rode away from the peloton and showed everyone on the team that we were capable of doing what we were there to do. Then, on stage 20, the team really worked to set me up. We rode part of the stage in the morning, made a plan, and then in the race I attacked right on the curve where [team director] Mike Neel wanted me to.

It was a short stage, maybe 70-80km of flat and then about an 18km climb. It wasn't a very hard climb, but the steepest part, 8-10 per cent maybe, was at the very beginning. The general classification battle was between [Bernard] Hinault, [Francesco] Moser and [Greg] LeMond, but they were all watching each other, so it made tactical sense for me to go early. I was right near the front on Bob Roll's wheel. I said, "Hey, Bob, behind you." He moved aside and I slipped through like a watermelon seed being pinched by two fingers. I got away clean and just kept wailing it all the way to the finish.

Procycling: This was obviously a huge personal achievement, but the pair of Giro stage wins for 7-Eleven also had larger implications.

AH: Absolutely. For me it was one of the defining moments in US cycling. Here was this first-of-its-kind team of Americans, and they were doing well in this big European race. LeMond [then a member of French team La Vie Claire] was really excited about it. He was telling [team-mate] Hinault all about us. Then he'd roll up to us and say, "Hey, Andy, I just told Bernie you guys are really good, so you have to win a stage." He told me I should race in Europe more, and that if I did well [in the '85 Giro], he'd lobby for me with La Vie Claire. He did, and that's where I went the next year. Before that I'd been on a one-month contract with 7-Eleven to race the Giro, but otherwise I was basically still an amateur, so really that was my big break.

A year later, as a member of the famous La Vie Claire powerhouse, Hampsten won the Tour of Switzerland, and then took the best young rider's jersey at the Tour de France, finishing fourth behind team-mates LeMond and Hinault. In 1987 he rejoined the 7-Eleven team, and then returned to the Giro in 1988.

Procycling: You had some great things happen after the 1985 Giro. Then in '88 you were back there, sitting well up overall coming into the Gavia stage. What happened next?

AH: I was second going into that day and I'd already won a stage a few days before. But everyone in the race knew that the Gavia stage was going to be most important, no matter what. I remember Gianni Motta, the 1966 winner, coming up to me before the race. He said to me, "You're going to win the Giro, and you're going to win it on the Gavia." I was like, "That's really nice of you to say so," but he was like, "No, I'm serious."

At that point the time gaps weren't that big. We knew some of the guys up there had had a nice run, but that they weren't going to be a threat, that they'd be gone by the first real day in the mountains. But [Swiss rider Urs] Zimmerman was pretty close to me on time, and we were both behind the race leader [Italian Franco] Chioccioli. Those were the people we were watching the closest.

Procycling: But the real story was the Gavia. Not a lot of people knew what to expect, did they?

AH: Everyone knew it was going to be a hard climb, but no one – racers or directors – really knew how hard. It wasn't very long, but it was really hard. Because of the weather they shortened the stage, so we started down in the valley where it was already sleeting and bucketing rain. Then, really early in the climb, we turned off the main road and it became a four or five per cent gradient until you got about a quarter of the way up. That's where the road gets really steep, as it turns to dirt and drops to one lane. It's a pretty dramatic change.

Procycling: What was the mood in the bunch at that point? Weren't some riders trying to call a temporary truce?

AH: Everyone was freaked out. I mean, I'd already been shivering uncontrollably on one of the earlier descents. There was no sunshine – it was nothing but rain and snow all day long. And yeah, some guys were saying, "Don't attack." The conditions were terrible. The riders really wanted to go slow and not race, but that wasn't happening. I could see that everyone else was terrified, so I just said to myself, "I'm going to do it. I'll save five per cent for the descent and go for it." I attacked right at the base because I could see that a lot of people were worried.

Procycling: So you reeled in most of an earlier break and went over the top in a blizzard along with Breukink.

AH: Yeah, I went over the top with Breukink and it was snowing for about the first 12km of this winding 25km descent. And that's where our team made the real difference. Other teams just weren't prepared; the first guy over the top, Johan Van Der Velde, got so cold he stopped halfway down the descent and ended up finishing 40 minutes back. 7-Eleven were the only team that had adequate warm clothing. We had a guy waiting at the top with a musette bag full of warm clothes for every rider. The team had gone shopping at ski stores before the stage and got wool hats and Gore-Tex ski gloves or diving gloves. They bought every useful item you could think of. They wanted the riders to know that they would have everything possible to help them out on the descent. They were also giving me hot tea the whole day. Team-mates were bringing stuff to me all the time. We had a really solid plan in place.

Procycling: How is it that your team had so much more foresight than the others?

AH: It was down to Mike Neel. Prior to that day, cars didn't have rain bags – the bag of warm, wet weather gear for riders that sits in the team car in case of the unexpected. That was a 7-Eleven innovation. Mike also gave us a great pep talk. He sat us down and told us this was our day. He said that it was snowing up there, but that the race was still going to happen, that they were ploughing the snow off the road, so it was going to be OK.

Procycling: So you got over the top. What was going on at that point?

AH: On the way up I put on a really long-necked warmer and a wool hat. I kept my neoprene gloves on the whole time because I figured that if my fingers went numb, I'd never get them back. At the top I struggled into a plastic jacket, and that's when Breukink caught me. On the descent I just had one gear because thing were starting to freeze, so I feathered the brakes all the way down and stayed in the 53x14.

The descent was a maddening number of turns and hairpins. I remember thinking, "Never look down, never look down." When I did look down at my legs once, they were bright red and I had a sheet of ice on the front of my knees and shins. I was like, "Man, I am way colder than I realise." Finally we hit this little village and it went from dirt to pavement and from snow to sleet. At that point I was just trying to get to the hotel and hoping it was past the finish line. If it wasn't, I might have stopped anyway and quit the race.

Procycling: You didn't stop, and in fact rode into the race lead. What was going through your head at the finish line in Bormio?

AH: I just wanted to get warm. I was really concerned for my health. I've never been in a place like that. Psychologically, no one can explain how tough it was – 25km of descending in freezing snow and sleet. It was the hardest thing I've ever done. Everyone who crossed the finish line that day had to dig incredibly deep to get there. When I talk to the other riders today, it's never, "So and so did this," or, "Yeah, Breukink won." It's, "Wow, you were on the Gavia in '88."

Procycling: After the Gavia stage there was still plenty of racing left. How did you protect your lead?

AH: The next day was a shortened stage because we were supposed to ride over the Stelvio, but that was closed because of the snow. But it was still a mountain-top finish where I managed to get time on Breukink who, at that point, was the only guy still close to me. There was also an uphill time trial, which I won, taking more time out of Breukink. And another mountain stage, where I let Zimmerman go in a break. I had a few team-mates with me and Breukink was with me too, but he wouldn't work, so I had to let Zimmerman go and he got about eight minutes up the road at one point. But there were four hours of racing left and we eventually took about 4-30 back.

Procycling: You ended up beating Breukink by 1'43", with Zimmerman in third. What kind of reaction did you get from the Italian cycling fans?

AH: I think they were pretty into it. It was kind of a down period for their riders so I wasn't going head to head with any of their big stars. And I really made an effort to speak Italian in the interviews, which I think really helped. But mostly, the thing with the Italians is that they love people who love to race bikes, and I certainly fit that bill.

La Dolce Vita

His Giro days are over, but Andy Hampsten is far from finished with Italy.

"It's the nicest place I've ever ridden a bike," Andy Hampsten says of his second home, Italy. "It's not that people recognise me, it's just that they respect cyclists. If I pull into a café, soaking wet after hours on the bike, the old guys in the corner are like, ‘Where did you come from? Why did you take the hilly road?' As a country, they're really into bikes."

For that reason, Hampsten has split most of the last two decades between his winter home in Boulder, Colorado, and a farmhouse in the Tuscan countryside. Tuscany is also base of operations for Cinghiale Cycling Tours, Hampsten's bike touring company. Each year he runs five week-long trips – usually two in the spring and three in the autumn. Besides regaling clients with tales from his racing days, Hampsten says his main role is showing people the Italian way of life.

"I teach people about the four-course lunch," he explains. "So many of my clients are used to grabbing a sandwich on the go, but when you're in Italy, you don't do that. It's great watching the Type A personalities. It's usually about the second or third day when they say, ‘Wow, I get it. I will have wine with my lunch.' Watching people slow down and enjoy each other is really fun.

"Eating and socialising is so important in Italy. Italians love to go home for a three-hour lunch. I mean, they work an eight-hour day, but they're just working to make enough money to have a house and feed the family. They'd much rather hang out with each other and have fun instead of burying themselves for 20 years and retiring early."

Hampsten has run tours all over Italy, but his favourite riding is in Tuscany, which he says has the perfect combination of weather, roads and scenery. "It has less rain in the winter, it's got no real traffic, and Pisa airport is just an hour away," he says.

"It doesn't have any huge climbs like the Dolomites or the Alps, but there are lots of intermediate hills. It's the middle-of-nowhere boonies next to an amazing coastline. I could never be bored riding a bike there. The roads are so twisty and turny that they seem designed for bikes. It's not a hard job leading bike tours in Italy."