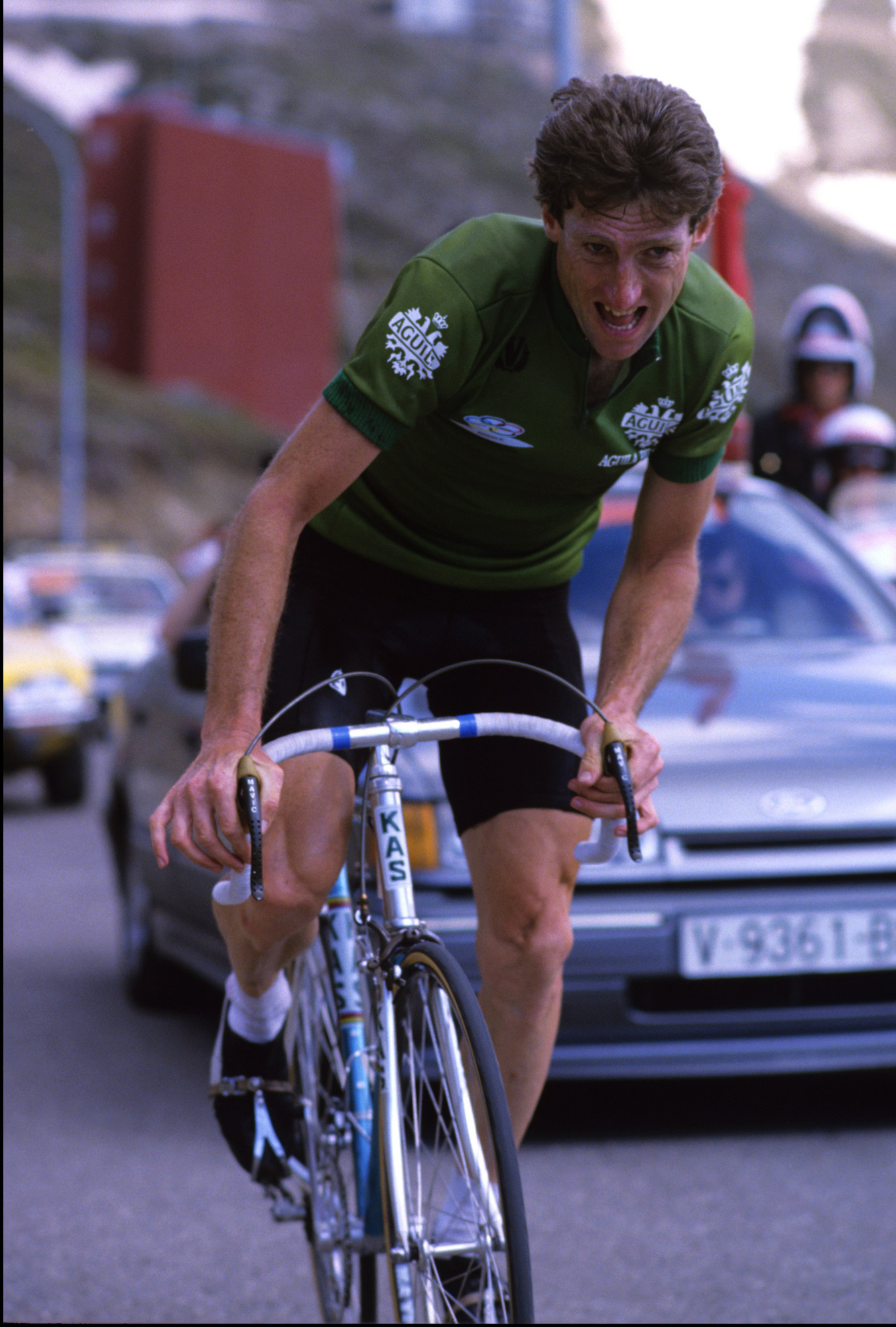

Classics King: Sean Kelly's phenomenal 1986 season

Procycling magazine remembers the season when the Irishman raced to over 30 wins, including Milan-San Remo and Paris-Roubaix

In 1986, Sean Kelly completed an almost singular record in cycling history: winning Milan-San Remo and Paris-Roubaix in the same year. Procycling looks back at an extraordinary achievement.

This article appeared in Procycling magazine issue 215 in 2016

Sean Kelly had such a remarkable career that it's hard to find a single high-water mark. Did he hit it early in 1984 when he won Paris-Roubaix and Liège-Bastogne-Liège among 32 victories that season? Or 1985, the dead-centre of his career, when the Classics man finished fourth overall in the Tour de France? And what about 1988, when he won the Vuelta a España, along with a seventh consecutive Paris-Nice? But perhaps 1986, when Kelly marauded around Europe with the same winning habit that characterised his peak years, has the best case.

He topped 30 victories that season, too, including the GC at Paris-Nice and the Tour of the Basque Country. There were the stages at almost every multi-day race he did, from February to mid-April: Valenciana, the Critérium International, and the Three Days of De Panne. He wasn't done yet. After the Classics, he went to the Vuelta and finished third, taking two stages.

But those successes merely provided the backdrop for two huge wins at Milan-San Remo and Paris-Roubaix. That particular double had been seen only once before, 78 years earlier by Belgian Cyrille Van Hauwaert, when cycling was very different. Milan-San Remo, in particular, had been transformed from endurance contest to the most complex, heady and tactically sophisticated race of the year.

The combination of San Remo and Roubaix in the same year has a particular shine. Rarity is one aspect of that, and John Degenkolb became only the third rider to achieve it last year [2015]. More than that, it's down to the races' different demands. La Primavera is by reputation the easiest to finish and the hardest to win because it offers so many tactical permutations. Meanwhile, Roubaix is the last word in suffering and survival. In order to win both in 1986, Sean Kelly had to be an iron fist in a velvet glove.

'I was going well that year'

"I was going well that year," Kelly tells us, ever the master of understatement. He was 29 in the spring of 1986, and engaged in an eye-watering schedule that even by the race-heavy standards of the time was crammed. By Paris-Roubaix, the Irishman had raced at least 34 times – 10 more than Degenkolb to the same point last year.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Kelly's contemporary, Eric Vanderaerden, who emerged as a key rival thanks to his feisty sprint at the end of hard races, viewed the Irishman as a throwback to the 60s and 70s.

"He [Kelly] was one of the last riders like Eddy Merckx, who rode from the first to the last race with the aim of winning," the Belgian told Procycling. "I think Sean was part of the new generation but living, working and racing like the old generation."

As Kelly recalls, the "totally crazy" schedule was down to his manager, the infamous aviator-shades-wearing Jean De Gribaldy. The Frenchman, known as Le Vicomte – The Viscount – discovered Kelly in the late 70s and he helped turn the Irishman into one of the riders who defined the 1980s.

"If you're not racing you've got to train, so why not just race?" was a favourite homily of De Gribaldy. So was: "Don't listen to journalists. If you listen to them saying you're going to be tired because you're racing too much, you're going to get tired mentally."

Kelly knew he was spreading himself thin but at the time it wasn't a concern.

"It's only when you look back towards the end of your career, and more so afterwards, that you look at the programme you were doing and it was totally crazy," he says. "There were things like going to Pays Basque and coming back for Roubaix. If you're really flying, you can handle that, but if you're not really in super shape, you can pay the price.

"In hindsight, other riders were doing it differently. There was this new idea that you focus on the Classics and then you have a break, and of course that's the way to do it. The problem was… Well, De Gribaldy was one problem, and the other problem was Kas."

Kas, a Spanish soft-drink producer, replaced Skil as the main sponsor of Kelly's team in 1986, and they saw Kelly's exploits in the Classics almost as extracurricular, because what really mattered to them was the Spanish season.

"I remember the big boss, Luis Knorr, saying to me: 'Tour of Spain, Tour of the Basque Country, Catalonia – if you can win those races, I'm happy. The Classics are always in cold weather and the Belgians only drink beer, not soft drinks.'"

There were deficiencies in the squad. Kelly was the only rider who could be entrusted with leadership at such vital, sponsor-pleasing races. Concern was academic: the Irishman had broad enough shoulders for the responsibility. But before the Spanish races, the Classics beckoned.

Conditions for Milan-San Remo were a characteristic blend of frigid and freezing across the Lombardy plains. They gave way to bright sunshine after the Turchino Pass, which conducted riders onto the Ligurian coast. Kelly would have seen danger everywhere: Giuseppe Saronni, Alfons de Wolf, Hennie Kuiper, Laurent Fignon and Francesco Moser were all past or future Primavera winners.

Kelly was also wary of Greg LeMond: "He was always a rider with a big sprint at the end of a hard race. LeMond, Bernard Hinault, Fignon – they were all trying to win Classics in the early part of the year."

He feared these GC riders most on the Poggio, "where they could create the difference and maybe go on to win". Nearing the Cipressa, however, with pressure mounting and the peloton getting nervous, Kelly became aware he had a second shadow – the Panasonic rider, Eric Vanderaerden. Wherever the Irishman went, he was tracked by the young Belgian, who represented a real threat if they hit the Corso Cavallotti together for a sprint; the Via Roma was out in 1986 because of roadworks.

"Vanderaerden was a nemesis and it was vice versa, I think," says Kelly. "He was a Classics specialist, good in the sprint – like me – and of course we had some huge battles in Classics and big tours."

That animosity extended to trying to pull each other off their bikes at the Tour de France, he recalls – an account vaguely confirmed by Vanderaerden who told us: "Could be. In the final, you do what you need to do and pulling jerseys was normal."

It could cut both ways, and contemporary rider Adrie van der Poel said sprinters often hung onto teammates' shorts to save energy getting over hills. What cameras and commissaires didn't see was fair game.

'When I moved up two or three places, Vanderaerden was there all the time'

Kelly said part of the friction with Vanderaerden came from the Belgian being a relatively new rider. Vanderaerden was forced to fight for every wheel.

"We were going to give him a difficult time and not let him break into that winning echelon too easily, which was something I had to do in my time when I was up against Francesco Moser and Jan Raas," says Kelly.

After the Cipressa, the peloton split and re-fused several times, and Kelly knew he had to do something to ensure he didn't sprint against Vanderaerden.

"He was latched onto my wheel. When I moved up two or three places he was there all the time."

Closing in on the Poggio's summit, Mario Beccia from the Malvor team broke off the front and was followed by LeMond. With Vanderaerden sticking to Kelly, the Irishman reached for one of the oldest tricks in the book: he faked a mechanical. He dropped his chain down the sprockets and started "cursing and swearing and giving the impression that I had a problem".

Vanderaerden can't or won't recall the incident, but Kelly recomposed himself and sprinted away, too fast for anyone to latch on. He made the junction and, looking back, saw Niki Rüttimann, LeMond's team-mate, bridging. Kelly couldn't let this happen as it would weight the sprint in favour of LeMond. Kelly forced his way to the front and drove hard. The descent came in the nick of time.

In a three-up sprint with Beccia leading out, Kelly had done the hard yards. LeMond was no match in the sprint, while young Vanderaerden finished 22nd, well behind.

In between Milan-San Remo and the Tour of Flanders, De Gribaldy sent the Kas squad to a training camp near Cannes in the build-up for the Critérium International. There, Kelly took the opening sprint stage, finished third on stage 2a and won the short closing time trial. The last race was a madcap dash to the airport afterwards.

"There was a flight back to Lille, but it was a very tight schedule after the race, and there were a number of times I went onto the plane with my skinsuit under my tracksuit," he says. "This was one of them."

Kelly's next race: the Three Days of De Panne, where he won stage 1 and finished second overall. He was ready for Flanders.

Working with Van der Poel

"There were many years I thought winning Flanders was on the cards," Kelly says. He finished second three times without winning – a record he shares with Leif Hoste. Reputation alone made him a favourite in 1986, but his build-up had been perfect, too.

Sometimes, however, form is not enough. In his autobiography, Hunger, Kelly said he traded assistance in the race to the Kwantum team's Adrie van der Poel for help the following Sunday in Roubaix.

It was pragmatism on the part of both men. Kelly needed allies down the line and Van der Poel had been dressed down by his DS, Jan Raas. Given the importance of a Ronde win to Kwantum, a Low Countries DIY chain, the pact was made.

It was activated when they made it to the finish together. Kelly took on the lion's share of the work in a four-man group that included Jean-Philippe Vandenbrande and Steve Bauer. Van der Poel waited patiently.

"In Meerbeke, I started my sprint early, and I knew Van der Poel was probably in my wheel as well, but I certainly gave it 100 per cent," says Kelly.

That night, while Van der Poel revelled in victory, Kelly flew to the Basque Country.

"Maybe if there had been someone on the team to take on the stage races, it would have relieved the pressure a bit," he says. But he still took three stages and the GC.

The day after, on the eve of Paris-Roubaix, he flew back to Belgium and drove down to Compiègne for the race's start.

'If you wanted to win at that time, you had to be better than Sean Kelly'

The 1986 'Hell of the North' was a filthy affair. Damp but not raining, so the worst of both worlds, according to Kelly: "When it's wet it can be mucky and the most difficult to ride over. Sometimes it's better when it's really wet because the stones are washed."

Over the first cobbled section, the front group thinned out and swelled again as riders caught back on afterwards. The natural erosion was accelerated by crashes at many sections of pavé. Greg LeMond wrapped his derailleur up in his spokes, ending his race.

Meanwhile, up ahead, Ferdi Van den Haute attacked on a late section of cobbles. Kelly, mindful of the assistance he had given Van der Poel in Flanders the week before, let the Dutchman make the running. A quartet of Kelly, Rudy Dhaenens, Van der Poel and Van den Haute came to Roubaix together. For the first time since 1943, the race didn't end inside the velodrome, but outside a local branch of the clothes shop, La Redoute – a race sponsor.

Van den Haute attacked with a kilometre to go, and Dhaenens couldn't react. Kelly sat tight, putting the pressure on Van der Poel, who duly opened up his sprint early, with the Irishman latching easily onto his wheel. That irresistible Kelly sprint saw him ease past his rival for the sixth of his nine Monument victories, and the rare San Remo-Roubaix double.

Van der Poel's reflections on taking up the chase inside the kilometre kite demonstrate the respect fellow riders had for Kelly at the time.

"For me it was always better to be second or third behind Kelly than a rider like Van den Haute," he said.

For Kelly, there was no respite after Roubaix. His punishing schedule continued through the spring: Flèche Wallonne followed three days later, Liège-Bastogne-Liège that next weekend and, two days later, he lined up on Majorca for the start of the three-week Vuelta. Kelly took two stages, the points jersey and finished on the podium behind Álvaro Pino and Robert Millar.

It was an incredible block of racing that was Kelly all over: relentless, demanding and abundantly successful. But the most ringing endorsement of Kelly's career and character comes from his fellow riders and rivals. Despite the competitive enmity, Vanderaerden admired Kelly's drive: "If you wanted to win at that time, you had to be better than Sean Kelly because he was there at every race. He was never a lazy rider. Get in a break with him and he rode. He didn't look around and see who was there."

Van der Poel was equally effusive: "He always rode with his heart, to do the best."

Sean Kelly turned the pursuit of victory into a crusade, and phenomenal success flowed in the golden period of his career between 1984 and 1988. For other rivals at the time, victories may have been rarer, but at least when they did come they had extra value for having been prised from the fingers of a legend such as King Kelly.

Procycling magazine: the best writing and photography from inside the world’s toughest sport. Pick up your copy now in all good newsagents and supermarkets, or get a Procycling print or digital subscription, and never miss an issue.

Follow @Procycling_magazine