Chris Hoy: Into thin air

The one kilometer time trial may have been controversially scrapped from the 2008 Beijing Olympics,...

An interview with Chris Hoy, December 14, 2006

The one kilometer time trial may have been controversially scrapped from the 2008 Beijing Olympics, but Scotsman Chris Hoy is determined to leave his mark on the event with an attempt at breaking Arnaud Tournant's famous sub-one minute world record in Bolivia next year. Cyclingnews' Ben Abrahams caught up with Hoy at the recent Track world cup in Sydney to discuss the logistics involved and the motivation behind such an attempt.

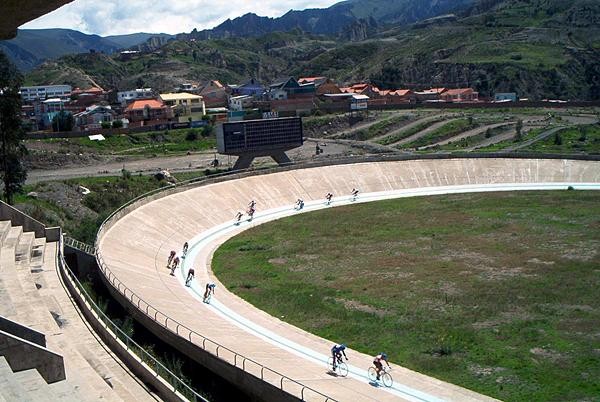

Reeling off Chris Hoy's achievements in major track championships since 2002, you could be forgiven for thinking that the 30 year-old from Edinburgh would be happy to hang up his aero bars and put the kilo to rest, which is where it now resides in Olympic cycling history. But despite the Commonwealth, World and Olympic titles, Hoy's personal best time of 1.00.711 is nowhere near the world record. Ever since Frenchman Arnaud Tournant scorched round the ageing concrete track near La Paz, Bolivia, in October 2001, clocking a staggering 58.875 seconds, the world record has been off-limits for anyone competing close to sea level.

The track in question, named the 'Velodromo Alto Irpavi' and situated at 3417 metres above sea level, is not the easiest place to get to - making the attempt a feat in itself. Hoy explains: "First of all you have to pay for drug testing to be there; to ratify the record, you obviously have to have dope control. You've got to have a UCI commissaire to oversee the track and make sure everything is okay. You've got the timing guys, to set up the gate and the timing equipment. You've got have a team doctor because of the altitude, there could be complications with your health and all that kind of stuff. You've got to have your coach, mechanic - it's a team of about twelve people."

With the team sprint being Hoy's day job for Beijing - to make way for BMX, the UCI dropped the men's kilo and women's 500 metre time trial from the Olympic track program in June 2005 - reacquainting himself with the kilo has to wait till after next year's world championships in Majorca at the end of March.

Is Hoy still reeling over the kilo's exclusion?

"It's under the pretense of being democratic but really it just seems like they made a decision and that's it. There's not much you can do, you can stamp your feet and make a big deal but in the end you'll just get bitter and twisted and only affect yourself."

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Two days after cruising to a gold medal in the season's first world cup in Sydney, Hoy said lackadaisically, "I'm not really putting much emphasis on the kilo at this time of year, it's all the team sprint. So probably mid-May but there's so many things to sort out. I'm just trying to let my management team sort it out and I'll focus on the training part."

Since Hoy holds the fastest kilo time ever recorded at sea level - his Olympic record set in Athens 2004 - the obvious question seems to be whether a similar ride at altitude would be enough to beat Tournant's time. "Well I don't know," he says cautiously. "It's very hard to tell because all I can really gauge it on is Arnaud's performances before he broke the world record. He was doing 1.01s at sea level beforehand which I can do as well. But because the track's on a different level altogether it's very hard to make comparisons."

"All I know is that if I'm going to break it anywhere then that's the place to do it. So all I can do really is try and get myself in the same shape or better than I was in Athens and step up there and just give it everything. The gearing will be different, different preparation for a 333 metre track. It's outdoor so there's other elements involved. There's a lot of preparation and thought that goes into it."

The pitfalls of such a huge effort in Bolivia's thin air are well known - Tournant reportedly passed out for twenty minutes after his ride - but the benefits in terms of reduced air resistance are equally large. "If you look at the splits from Arnaud's record, he gets up to a really high speed but it just plateaus and normally that never happens in the kilo," explains Hoy. "Normally you tail off. Because the air is so thin, if you get up to a really high speed it's easier to hold it, well, in theory."

Apart from the bleedingly obvious matter of breaking a world record, Hoy cites the need for "an interim goal between now and Beijing", but denies it has anything to do with putting the kilo back in the media spotlight as a means to reinstating it in the Olympic cycling program. "If you look at the athletes who are still riding in the 500 and the kilo and you see a world record broken yesterday in the 500, the athletes are still there. It's not going to cost any more than a set of medals and the track time to put on an amazing spectacle, but they [the UCI] are not going to change their minds."