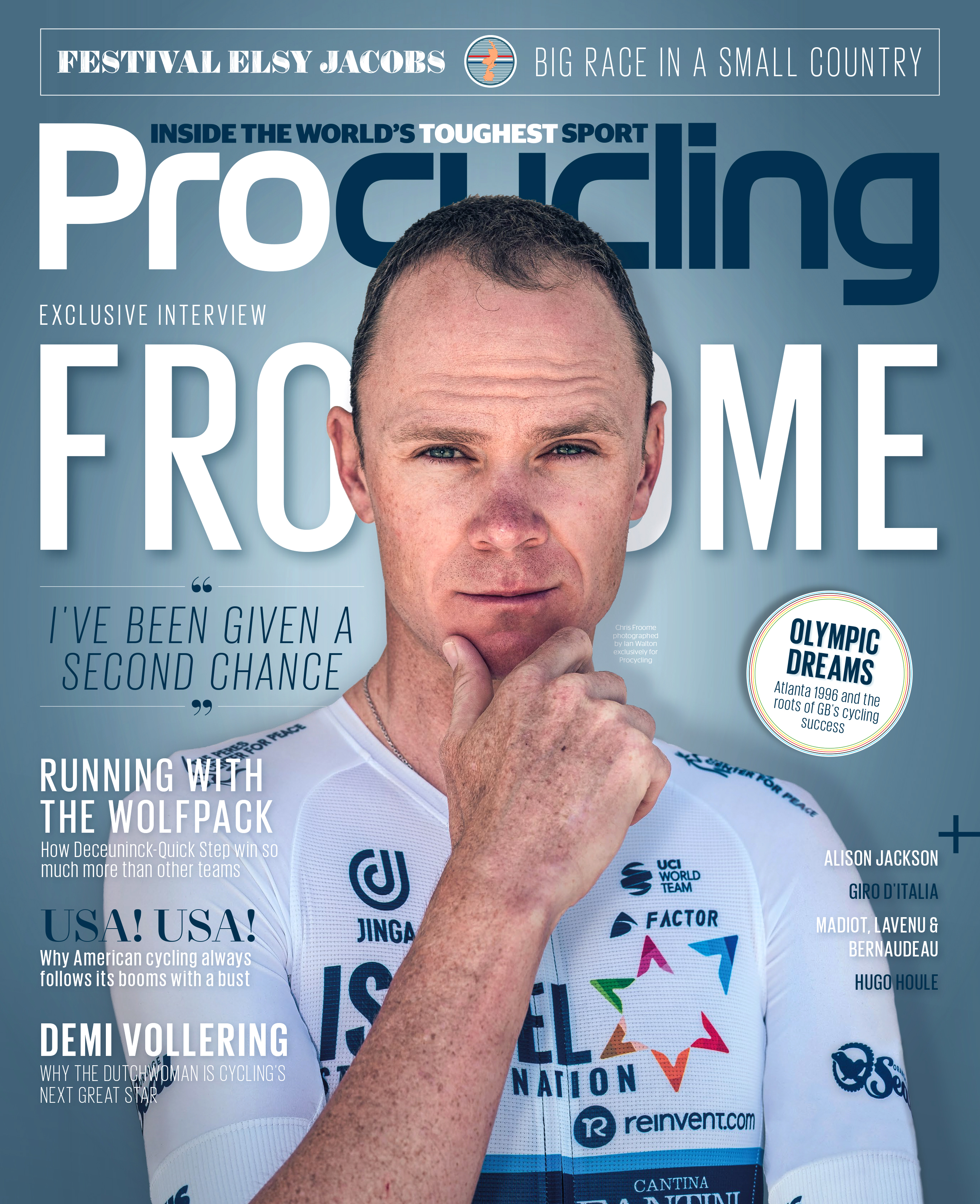

Chris Froome: The long climb

Procycling magazine's full-length interview with the four-time Tour de France champion

This article originally featured in Procycling magazine issue 284, August 2021. Subscribe to Procycling here.

Cycling’s landscape couldn’t have changed more than in the two years since Chris Froome’s career-altering crash at the Critérium du Dauphiné in June 2019.

Back then, Tadej Pogačar was a neo-pro a few months into his first season in the WorldTour, Primož Roglič was still frequently referred to as a former ski jumper, the Israel cycling team was a second-tier squad trying to secure wildcard race spots and Froome was one of the favourites to win a record-equalling fifth Tour de France that summer.

Today, Froome remains the most successful Grand Tour rider in the peloton, but the rider who won seven titles between 2011 and 2018 isn’t the one that we’ve seen these last two years. There’s still no way of knowing for sure if he’ll ever be that rider again.

It was on June 12, 2019 when everything changed for Froome. In a split second, as he rode downhill and briefly took his hand off his bars while doing a course recon of the Dauphiné’s time trial in Roanne, he careered high speed into a wall. He fractured his right femur, his elbow and multiple ribs as well, as well as suffering internal injuries. He was initially bed and wheelchair bound, and had to relearn to walk.

Having once seemingly been unbeatable in grand tours, Froome’s results two years on read more like those of a domestique, tasked with carrying out their role before sitting up to save energy beforee the finish. While Pogacar, Roglic and Egan Bernal have become the Grand Tour riders to beat, Froome has been finishing in the gruppetto, often simply trying to survive to the line.

“It’s phenomenal. I almost feel as if the crash has taken me back to being a neo pro, in a very strange way, and I’m sort of trying to make it again and trying to get back to that top level again,” Froome tells Procycling over a Zoom call. “It’s almost as if I’m starting from the beginning and I’m trying to get up there. Which is, yeah… a position I never expected to be in at the age of 35.”

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Lying in intensive care covered in plaster cast, days after the accident, Froome declared his intention to return to racing. In the months and weeks since, he’s repeated the same line, that he can and will get back.

Yet looking at the cold hard facts, it’s hard to see Froome winning a Grand Tour in the near future. Froome turned 36 a few days after we spoke – only one rider has ever won the Tour at that age or older and that was Firmin Lambot 99 years ago in 1922.

Few riders have ever been able to completely come back after sustaining injuries as severe as Froome’s - that he’s even competing again at all is a feat in itself. His highest GC results since are two 47th places at the UAE Tour and this year’s Dauphiné, the latter shortly after our interview. This July, he’s riding the Tour in a supporting role for team-mate Michael Woods, not challenging for the GC himself.

This is all before even considering how the competition around Froome has also shifted in the last two years. Hopes of Froome winning the yellow jersey in the years to come seem optimistic to even the most sympathetic of observers.

Even considering Froome’s situation when we speak tells its own story.

It’s mid-May, and Froome is halfway through a three-week altitude camp in Tenerife. There’s nothing unusual in that; it’s long been his pre-Tour routine at this time of year. But the aim and look of the camp couldn’t be more different than those of the pre-crash Froome.

For a start, the Ineos Grenadiers Tour longlist of riders, which Froome used to head, are training on the island at the same time, fine-tuning their efforts to win back the yellow jersey with a host of staff at their disposal; Froome, meanwhile, is there with just three of his Israel Start-Up Nation team-mates, staying in a nondescript, self-catered villa. Winning isn’t on his mind; his training is based around power targets, such as those required to get him into the foot of a race’s final climb in the front group, not even to the top of it.

Froome admits that when considering his recovery, he hoped he’d be further along than he is by now.

“I think I really hoped to be back riding GC last year in my head, but it just wasn’t possible. With the injuries I had and with the soft tissue that was damaged, it was one thing having the broken leg healed in two places where I broke my leg, but all the metal work, I think, that went along with that was actually pretty destructive to the soft tissue, especially around my hip,” he says.

“I’ve got a big open, big sort of scar down the length of my hip where they had a plate in there, sort of hooks onto the top of my trochanter and that was a big piece of metal. I think putting that in and taking that out three, four months later, that caused a lot of damage. I mean, from a muscle point of view and a left-right balance, I’m getting very close if not back to exactly where I was pre-crash.

"I think all that’s missing now is literally the hard miles, the hard training and getting the fitness back again with that depth of racing. And in the meantime, the level of racing hasn’t gone any slower, that’s for sure, with all the new guys coming up in the sport.”

A second chance

Few riders have ever achieved success on the level that Froome has. With four Tour titles, a Giro and two Vueltas to his name the Briton sits joint fourth overall in the all-time grand tour winners’ league.

For almost all of the 2010s, he was the rider at the front of Grand Tours doing the damage. To now be getting dropped, unable to keep up with the pace of his rivals, you’d imagine would take some adjusting to.

Not many multiple grand tour winners keep riding when they’re no longer in a position to fight for the victory. Froome, however, at least publicly, is able to put a positive spin on his new status near the back of the bunch.

"It’s been quite enlightening actually. As you say, for years I’ve been up at the front of Grand Tours – the gruppetto was a place that I would actually never be in really in a Grand Tour. And racing the Vuelta last year was... it was an experience and quite a humbling one," he says.

"It was almost as if it opened my eyes to the other side of the race that I haven’t seen for so many years. And also the camaraderie between cyclists, seeing guys from other teams helping each other to get to the finish and literally just surviving and trying to get to the finish within the time cut. It was quite a nice side of cycling that I hadn’t seen for a while."

Froome has always been a polite, considered interviewee. He’s amenable, answers at length and is generous with his time to talk and for Procycling’s photographer. Yet you often get a sense that the public Chris Froome and the private Chris Froome are two separate people and only a select few get to know the latter. Chris Froome the racer talks at length but trying to dig deeper to Chris Froome the man has never been straightforward, he gives so little away.

When asked about his time in Los Angeles over the winter of 2020 with his family, he reverts to talking about the weather and how that made it easy to train. Even trying to gain some insight from a playlist he posted on his Strava account in May, which garnered attention on social media for its eclectic mix, generated little.

“Personally I prefer some of the older 80s, 90s stuff, that’s definitely my cup of tea,” he replies.

One thing you do repeatedly get the sense of is that the lifestyle of a pro cyclist was as much, if not more, of a motivation for him to want to return to the sport post-injury, than racing. He speaks repeatedly about how much enjoyment he has on training camps, and the relationships that exist within a team. He stresses that the biggest lesson he learned the last two years is how much he doesn’t want to stop being a cyclist, even though, considering what he’s won already, he easily could.

“Certainly, from a mental point of view, it’s put a lot of things into perspective for me,” he says. “It was just a line drawn straight from where I was previously in my life, and my career I guess, so it was a huge adaption. But there are so many positives I can take away from it. I genuinely feel as if I’ve been given a second chance now, I’ve been given a second chance to come back to the highest level of professional cycling. I’m just so grateful for it.

"I mean, a lot of people see the whole crash as a negative… Yes, it is a negative, it took me back a long way. But at the same time it’s tested me, tested my motivation, my love for the sport. Made me ask questions, if this is what I really want to go through all over again, knowing that it’s going to take years of hard work just to get back there. The answers to those questions are definitely yes. I love it, I love being up here, the altitude training camps. I love doing it.”

Progress

Froome’s dream remains winning a fifth yellow jersey, and moving into that elite club of five-times winners. Still, it’s hard to ignore that next year will be four years since Froome won the Giro, his last Grand Tour - Laurent Fignon was the last rider to wait longer than that between grand tour wins in 1984 and 1989, and he didn’t endure any career-threatening injuries.

Froome talks of his own stubbornness of not wanting to give up yet, but what might it take for that to wane?

“I think if I stop seeing progress, if I stop seeing things that I’m measuring on a daily basis – things like from the morning activation exercises improving, from numbers on the bike improving, left-right balance improving - if I stop seeing things moving in the right direction there, if I basically just stopped improving or even sort of headed back the other way… and that coupled with performances on the bike going down as well, then I’d be concerned,” Froome says.

“But, up until now, that hasn’t been the case. Things are progressively getting better and better, and sensations are getting better, so I’m going to keep at it and stay on track.”

The other unknown element within Froome’s comeback is his transfer to Israel Start-Up Nation. All of his Grand Tour wins came at Sky/ Ineos, a team with an embarrassment of riches when it came to resources and rider support. Israel is a team with a similarly endless pot of cash - some reports stated his signing fee was €15 million - yet having only moved up to the WorldTour in 2020, it lacks the same level of experience.

Froome has had to get used to new coaches, new directeurs, a new bike. Only Gary Blem, his longtime personal mechanic, made the transfer with him. Even by mid-May, Froome still hadn’t met many people on the team. Again, however, he talks positively of the challenge and how refreshing the experience has been.

“I think there are obviously things I’ve learned over the last 10 years. I’ve come in here and I think I can see really quickly where we need to work on things, and other things that the team have got bang on already, have got dialled straight away,” he says.

Israel Start-Up is a team that’s not been without its controversies, however, and as one branded with the name of a state, accusations of sportswashing the country’s record on foreign policy, are hard to avoid. At the time of our call, conflict between Israel and Palestine was headline news, with 11 days of bombing during May resulting in 253 fatalities in Palestine, and 12 in Israel, according to the United Nations.

Sylvan Adams, the team’s co-owner, has repeatedly said the team aims to be ambassadors of peace. Their kit features those words, in reference to the Israeli Innovation Centre - and Froome stresses he believes Adams’ drive is this. Yet separating sport from politics seems increasingly difficult, and when asking Froome whether it can be done, it’s evidently a subject he doesn’t want to be drawn into.

“I think promoting peace through sport is a massive part of the team’s ethos. No one wants to see these kind of situations that are arising at the moment in the Middle East. It’s certainly not a happy situation. We all hope for a good, calm resolution in the near future,” he says.

Another subject he’s reluctant to be drawn into is the ruling against former Team Sky doctor Richard Freeman, this spring, where he was found guilty of ordering testosterone “knowing or believing” it was to be given to an unknown rider, charges he has denied and is now appealing. Froome says little more than he didn’t follow the case to comment, and stressed he had nothing to do with the story.

Whether Froome will ever win a Grand Tour again, and if he does how long it might take him, is unknown. As things stand, he’s unable to quantify the gap between his level pre-crash, and where he’s at now.

“I’d say on the longer efforts I’m getting pretty close, I’m pretty close, if not exactly where I need to be, or where I was pre-crash in longer, sort of one-hour-plus efforts. So in terms of fitness I’m getting there. Where I’m still lacking is the more explosive, shorter stuff, so your one, five to 10-minute sort of short, sharp efforts. That’s where I need to work most at the moment,” he says.

Even then, Froome’s aware that his 2019 level might not even be enough. The cycling landscape has shifted so much in the last two years.

“I can only really look at the guys who I was competitive with at that time and seeing if they’re still up there and still able to perform, which most of them are. First off: get to where I left off, and take it from there.”

Procycling magazine: the best writing and photography from inside the world's toughest sport. Pick up your copy now in all good newsagents and supermarkets, or get a Procycling subscription.

Sophie Hurcom is Procycling’s deputy editor. She joined the magazine in 2017, after working at Cycling Weekly where she started on work experience before becoming a sub editor, and then news and features writer. Prior to that, she graduated from City University London with a Masters degree in magazine journalism. Sophie has since reported from races all over the world, including multiple Tours de France, where she was thrown in at the deep end by making her race debut in 2014 on the stage that Chris Froome crashed out on the Roubaix cobbles.