Can fabled Formigal fill Tourmalet-shaped hole at Vuelta a España? Preview

With stage 6 re-routed, the Vuelta returns to the scene of a famous ambush and Froome's most wretched day

When the Vuelta a España organisers issued their announcement on the complete redesign of Sunday’s stage 6, much of the peloton would have breathed a sigh of relief, but it might have sent a shiver down the spine of Chris Froome.

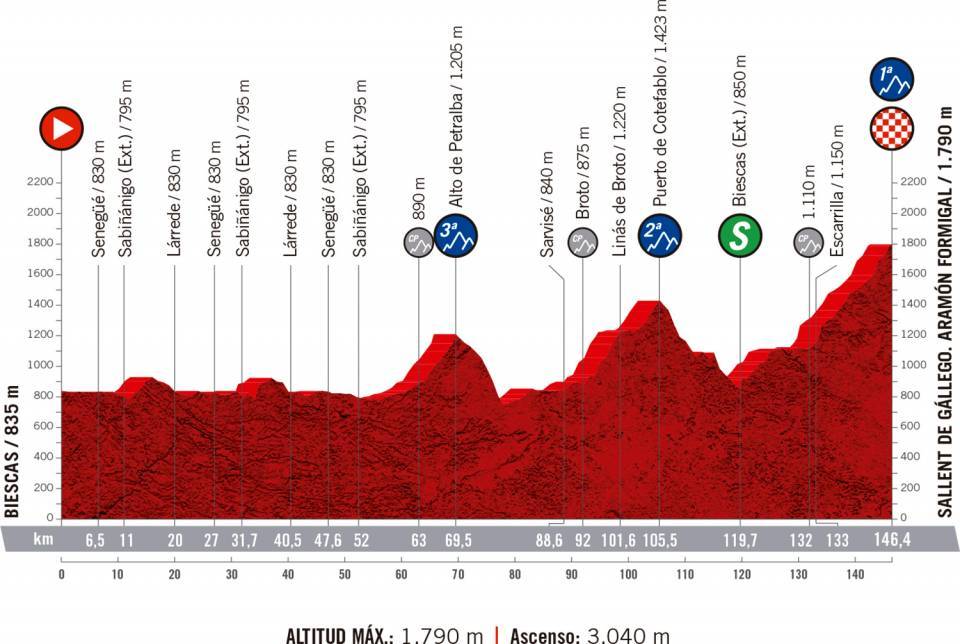

Coronavirus restrictions have effectively shut the French border to the Vuelta and scrubbed the eye-watering three-col menu of the Pourtalet, Aubisque, and Tourmalet off the chalkboard. The replacement whipped up by the organisers is still a hearty affair but far more digestible, with two comparatively straight-forward climbs ahead of the summit finish at Formigal.

And yet it’s that last word that will have induced the shivers in Froome, as well as raising a sense of excitement for Sunday that seems exaggerated for the profile we now have in front of us.

Formigal was the setting for one of the all-time great Vuelta stages – arguably one of the all-time great Grand Tour stages – and the setting for one of Froome’s most wretched days on a bike. On a stage of just 118km, at the back end of the second week of the 2016 Vuelta, the then three-time Tour de France winner was well and truly ambushed by an ad-hoc alliance between Nairo Quintana and Alberto Contador in a day-long break.

Froome and his Sky teammates were slow to start, unsuspecting that when Gianluca Brambilla stretched the peloton in the opening kilometres, Quintana and Contador – both with teammates – would jump on the case. Froome was immediately on the back foot, scrambling through the splits. It still seemed unthinkable this would go all the way, but Quintana and Contador put their heads down in their 14-man break and never looked back.

Froome, meanwhile, found himself with just two teammates, the rest of the Sky riders stuck in one of the groups at the very back. In a high-wire act of tactical balance, Movistar forced the pace in Froome’s chase group, careful not to get to close to their leader Quintana, but, crucially, sure to not let Froome’s teammates back into the fold.

And so it continued, all the way to the final climb to Formigal, where Alejandro Valverde taunted Froome further with a number of little digs. By then it was every man for himself, and Quintana dropped Contador in the final couple of kilometres. Brambilla, who’d sat in the wheels for much of the day, was fresh enough to out-kick Quintana for the stage win but it seemed fitting, given he’d kicked the whole thing off.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

By the time the dust settled, Quintana, who’d started the day in the red jersey, put 2:37 into Froome to extend his overall lead to 3:37. There was nothing to separate the pair on the final two mountain stages, but Froome put 2:16 into Quintana in the stage 19 time trial – which by then was not enough. Standing next to each other on the final podium in Madrid, 1:23 between them, it was clear Formigal was where the 2016 Vuelta was won and lost.

Does lightning strike twice?

Will the 2020 Vuelta be won and lost at Formigal? Parallels with 2016 are underlined by the fact that Sunday’s stage is almost identical, with a couple of short loops around the start down of Biescas followed by the same final 100km. However, it would be quite something for lightning to strike twice. What made that day so decisive and ultimately historic was the element of surprise, and that’s the thing about ambushes – you never see them coming.

When you hold the new stage 6 up against what was previously drawn up, it certainly looks far less decisive. The organisers attempted to spin the new stage as a like-for-like replacement, with three mountains substituted by three mountains, but the new climbs pale in comparison with their counterparts.

The category-1 Col du Pourtalet is replaced by the category-3 Puerto de Petralba, 6.5km at 5.1 per cent. The hors-category Col d’Aubisque is replaced by the category-2 Puerto de Cotefablo, 13.5km at 4.1 per cent. And finally, the highly-anticipated summit finish on the mighty hors-category Col du Tourmalet at 2100 metres, is replaced by the category-1 ascent to Aramon Formigal, 14.5km at 4.6 per cent. Those aren’t the sort of names or numbers that will strike fear into the peloton.

After a rolling start, the Petralba tops out with 77km to go and should see a break and a full bunch at the top. The Cotefablo will be a sterner test of the legs and can be said to be done a disservice by the figures, given its average gradient is mitigated by a flat section in the middle. Similar can be said of the final ascent, which is preceded by a 5km climb and 5km plateau, and the organisers have sought to emphasise as such, strainingly billing it as "27 kilometres of continuous ascent".

The official climb measures 14.5km. The first couple of kilometres are easy, followed by a kilometre at seven per cent but then three more kiometres of much more gentle stuff. The middle section features seven per cent gradients broken up by two sections of flat terrain, and so the crucial part of the climb looks to be the final 4km, with an average gradient of around seven per cent and one or two steeper pitches. Still, it’s largely a steady power climb on well-surfaced roads – a far cry from the steep goat tracks the Vuelta has become known for.

It’s hard to see race leader Primoz Roglic, who still somehow looks fresh after his rollercoaster Tour de France and Liège-Bastogne-Liège victory, suffering much, and the same can be said of his teammate Sepp Kuss. With the exception of the disappointing Tom Dumoulin, Jumbo-Visma are once again the strongest team in this race, even if Ineos did most of the damage on Tuesday and Thursday, with Richard Carapaz looking poised in third place. Second-placed Dan Martin (Israel Start-Up Nation) looks in his best form for years, while Enric Mas (Movistar) looks assured in fourth ahead of Hugh Carthy, who has taken sole leadership at EF Pro Cycling. Those five are within 38 seconds of each other, with Felix Grossschartner (Bora-Hansgrohe) and Esteban Chaves (Mitchelton-Scott) also looking sharp further down the top 10.

Whether Sunday will simply see a continuation of that trend remains to be seen. On paper, as mountain stages go, it doesn’t look too imposing. And yet, the same could have been said of the first two stages, and they produced the sort of GC movement that’s unheard of so early in a Grand Tour. The Vuelta is an unruly affair in the most normal of seasons, let alone these unprecedented times, and there’s a sense anything could happen between here and Madrid.

And then there’s the mystique of Formigal itself, which was the Vuelta’s first proper summit finish in 1972. Back then, Spanish climbing legend Jose Manuel Fuente – aka 'El Tarangu' – wrote himself into Vuelta history with a performance for the ages. He was already a double stage winner in the Tour de France and King of the Mountains in the Giro, but he was deemed by Vuelta organiser Luis Bergareche not enough of a name to lead the Vuelta. With a huge gap at the foot of the Formigal, Bergareche pleaded with his team to tell him to wait up, but he ignored those pleas and put nearly nine minutes into his rivals by the summit to take the overall lead, sealing the first of his two Vuelta titles soon after.

Sometimes, the reputation of a mountain speaks louder than its statistics.

Patrick is a freelance sports writer and editor. He’s an NCTJ-accredited journalist with a bachelor’s degree in modern languages (French and Spanish). Patrick worked full-time at Cyclingnews for eight years between 2015 and 2023, latterly as Deputy Editor.