Cadel Evans: The legacy of Australia's greatest rider

Tour Down Under Countdown starts here

This feature first appeared in the January issue of Procycling. To subscribe to the magazine, click here.

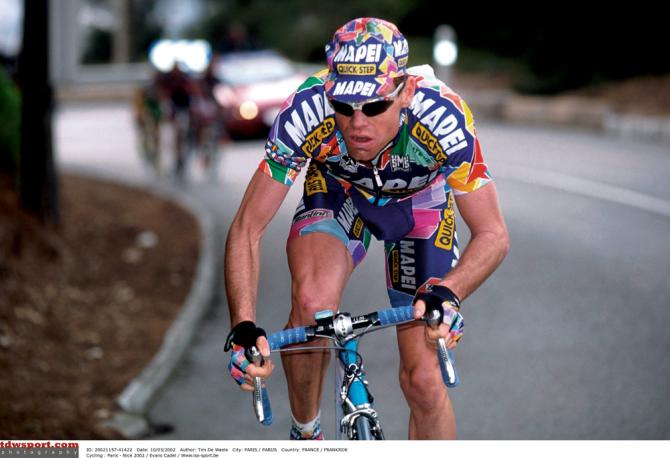

As the first Australian to win the Tour and the Worlds, Cadel Evans is assured a prime place in the record books. Yet for much of his road career, the ex-mountain biker was a nearly man, seemingly always lacking the killer instinct to turn podium places into victories. But in the latter years frustration finally turned to glory. When his career terminates in February at the Great Ocean Road Race that bears his name, it's going to be emotional. "I'm just hoping it doesn't bring tears. It's going to be hard to race for the last time." We examine the career of this sensitive and history-making sportsman.

When a champion rider retires, and colleagues are asked to recall their first sighting, meeting or memory of them by way of tribute, usually they talk about a big win or a particular ride.

But ask Damien Grundy, mountain bike coach and mentor of Cadel Evans, to reveal his earliest recollection of the first cyclist to go from being a World Cup mountain bike champion to Tour de France winner and he refers to a "pretty miserable day" at the ski town of Thredbo in the Australian Alps in New South Wales in 1993. Specifically, Grundy cites the moment when his wife, Rachel, looked out the window and saw "that" 15-year-old "kid who keeps coming into the [bike] shop" in Melbourne where Grundy was then working.

Grundy's ears pricked when Rachel mentioned Evans, who was outside racing in a youth race at the Australian Mountain Bike Championships. He got up and looked through the window to watch the boy in action. "I thought, 'I wonder if he needs a hand?'" says Grundy as he talks about his protégé two decades later. "So I made a point of going to the finish line.

As it turned out, he finished second. I went up to him and introduced myself and said, 'Hey, I work in the shop. I've done a bit of racing. If you want a hand, a bit of advice, I'd be keen to help you.'

"That was really the first time I noticed Cadel. I don't think he had raced much. It was one of his first few races. He was second so obviously there was some promise there."

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Grundy is speaking at a lunch hosted by one of Evans's Australian partners, Ernst&Young. It is the day after Australia's first Tour winner returned to his homeland to launch the route for the last ever race of his career, the Cadel Evans Great Ocean Road Race, set for 31 January to 1 February, starting and finishing in Geelong, a town south-west of Melbourne.

Grundy’s reference to seeing "promise" is an understatement. In 1995 he joined the Australian Institute of Sport as a mountain biker and went on to win the 1998 and 1999 UCI MTB World Cups and compete in the 1996 and 2000 Olympic Games in the discipline. He then made the unusual transition to the road, setting him on a course to becoming Australia's first Tour de France champion.

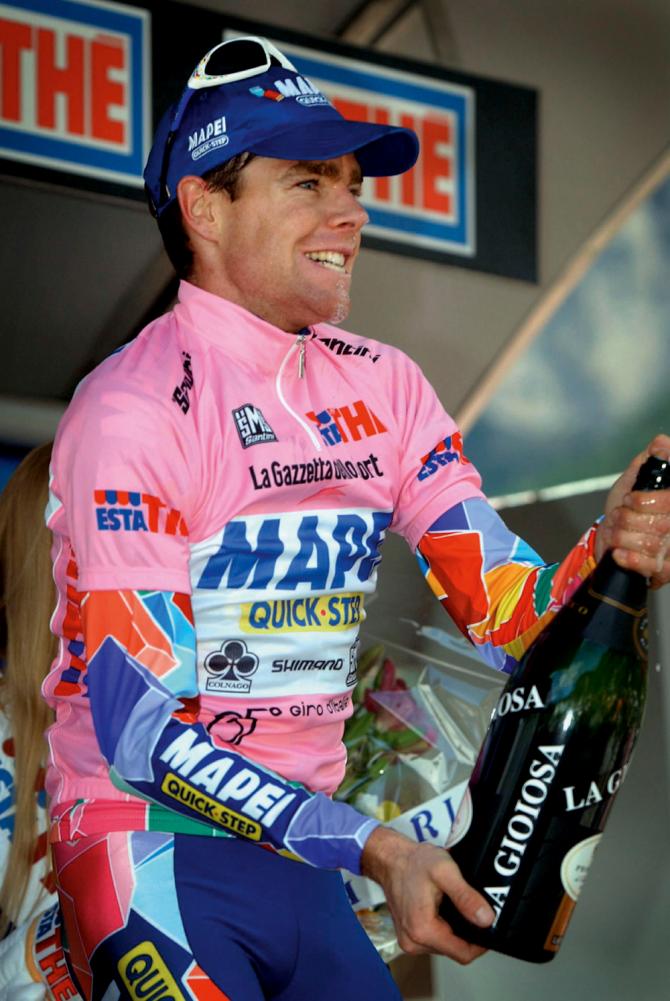

While Evans's career should not only be remembered for that historic victory in the Tour, its significance is given even more weight by the struggle he endured to achieve it. That included eighth on his Tour debut in 2005, a fourth in 2006 and second places in 2007 and 2008 in which he agonisingly finished a mere 23 and 58 seconds shy of winning.

Even 2014 had successes, such as his stage win and second overall in the Tour Down Under, four days in the leader's pink jersey and eighth place at the Giro, two stage wins plus first place overall at the Giro del Trentino and two stages of the Tour of Utah.

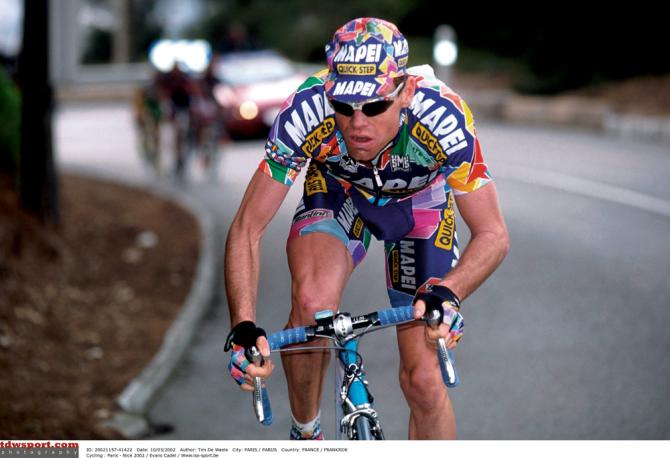

It was 1999 when Evans's potential on the road began to emerge. While still a mountain biker for Volvo-Cannondale, Evans won the Tour of Tasmania GC by winning the last stage to the top of Mt Wellington, prompting commentator Phil Liggett to declare: "This kid could win the Tour de France one day."

It would have been easy for Grundy to have been left in Evans's wake as his impressive career turned to the road in late 2001, where he has remained ever since. But it is a measure of Grundy's impact that Evans, now 37, still credits him and the lessons he learned in those early days of his career for much of the success he has enjoyed, notwithstanding the importance of Italian Aldo Sassi, who passed away in late 2010.

"It's strange that still today when I do something, at age 37, I go. 'That's right – it's because he told me that when I was 15," Evans says of Grundy's long-lasting impact on his career, when speaking to the same audience that has just been listening to Grundy reminisce.

A key point to reinforce is that Evans is a winner. It's necessary because his near misses are so well documented.

He admits that he still laments the three grand tours that slipped through his grasp: the 2007 Tour de France, where he was second to Alberto Contador by 23 seconds; the 58-second loss to Carlos Sastre in the following edition; and the 2009 Vuelta where a slow neutral service in the Sierra Nevada destroyed his chances of moving into the race lead.

For all the noted peculiarities of his persona that – fairly or not – generated much public and media comment (he has a reputation for being shy, slightly awkward and introverted), Evans was a racer who always sought victory. Not that Evans can't laugh at himself, as he showed with his amusement over the reactions to his "Don’t stand on my dog or I'll cut your head off" remark that he made at the stage finish at Prato Nevoso during the 2008 Tour, when his wife, Chiara Passerini, and their dog, Molly, were waiting nearby. Evans even had his own line of "Don’t Stand on my Dog!" T-shirts printed.

But listen to Grundy and you begin to understand how his winning mindset was honed; likewise Evans's meticulous attention to detail and preparation, and his reluctance to chest-beat his intent.

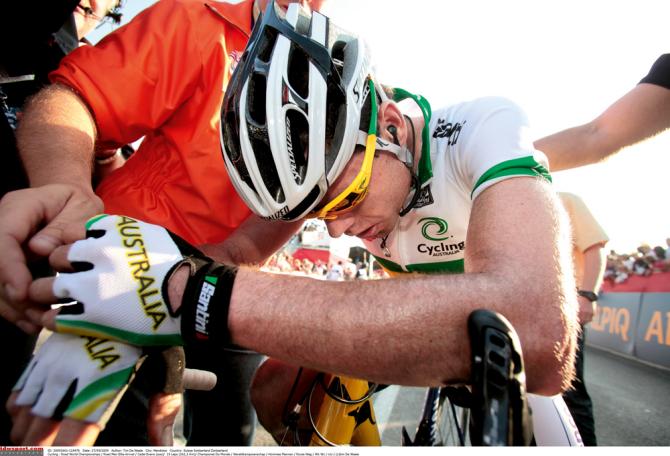

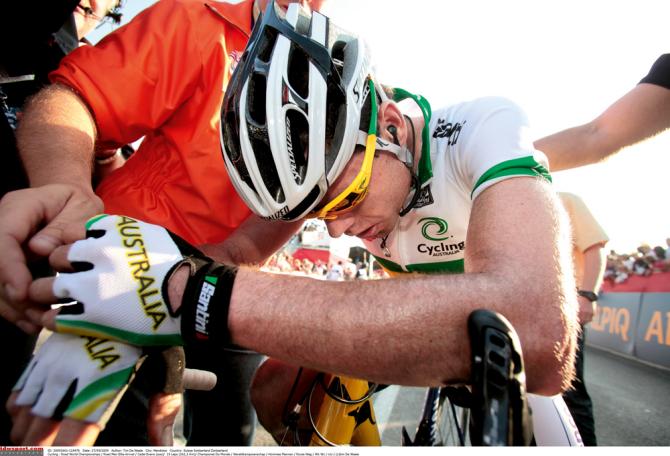

Evans says he rarely cries, though his eyes did well up as he stood on top of the Worlds podium in 2009, and at his 2011 Tour winner's press conference inside the Grenoble velodrome when he was asked about Aldo Sassi's impact as a trainer and friend.

Recalling Grenoble, where he took the yellow jersey to secure his Tour win, Evans admits his usual steadfast ability to contain his emotions before the media was scuppered when he was asked about Sassi who "had just passed away [from a brain tumour], nine months previously.

"It made me realise that all the things Aldo had said and the way we rode the race would have made Aldo so proud… It was what we had been working on for so many years. It was confirmation of his belief and philosophy because his whole career was pretty much geared towards the goal of trying to win the Tour de France."

The first time Evans says he did cry was after that slow neutral service in the 2009 Vuelta won by Valverde who was, then in a court battle over his involvement in Operación Puerto that eventually saw him banned two years and return to competition in 2012.

He says it was "not so much [because] I didn't win, but the situation I had been put in. I felt undeserved by that whole situation. It was probably [because] someone who was not meant to be racing in our sport at that moment was given the win."

But despite low moments such as these, Evans maintains that one of the good things about his career has been that, "You never know what's going to happenen the day after. And a week later, luck turned my way on the roads to Mendrisio."

Evans is readying for his heart strings to be pulled before he retires. He was certainly taken back by the words of Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott – an avid cyclist – in a recorded video screened upon his return to Australia at his welcome back lunch.

Abbott praised Evans for his "grit and determination" and for having "stamped yourself as one of the all time great Australian sportsmen and perhaps the toughest man to ever represent our country." Evans said he was “embarrassed and overwhelmed, actually."

But the decision to retire, Evans adds has not been easy; even if it was one that he was clearly contemplating during the Giro in April when, after stage 17 and the day after he lost a whack of time as he battled against the snow and wind – he spoke to The Sydney Morning Herald of his fear on the descent off the Gavia.

This from a former mountain biker who would normally list an ability to descend faster than most as one of his strengths.

With all hope of an overall victory in the Giro gone in his last bid for a grand tour, Evans said of the 16th stage from Ponte de Legno to Val Martello,

Back in Australia, Evans confirmed that retirement was definitely crossing his mind after that Giro – in which he finished eighth – and after skipping the Tour in July for the first time in 10 years in a prearranged schedule.

The decision to retire may not have been announced until after Evans rode the Vuelta for Spanish team-mate Samuel Sánchez but as Evans admits: "When the result didn't come [at the Giro] I could accept that maybe I am not capable of winning a grand tour any more. It makes it pretty easy. If I can't win it, I don't necessarily want to be in it."

But the process of locking in that decision was not so simple. "There is a massive amount of motivation and momentum behind what I do that has got me to do all the work that is required – the training, travel and sacrifices and discipline you need to perform in any sport – or anything…" Evans says.

"To put the brakes on that momentum is not that easy. There is quite a force behind it after all these years."

Asked if he is ready for the emotion of that final day, he says: "I'm just hoping it doesn't bring about the tears. It's going to be hard to pin on a number for the last time, race for the last time and probably come in for the last kilometre for the last time. It could be difficult for me but at the same time I've really given everything to this sport."

Looking back on the whole journey, does Evans have any major regrets? "I do have a few," Evans says. "But overall I go away having achieved or having been able to experience far more than I even dreamed of."

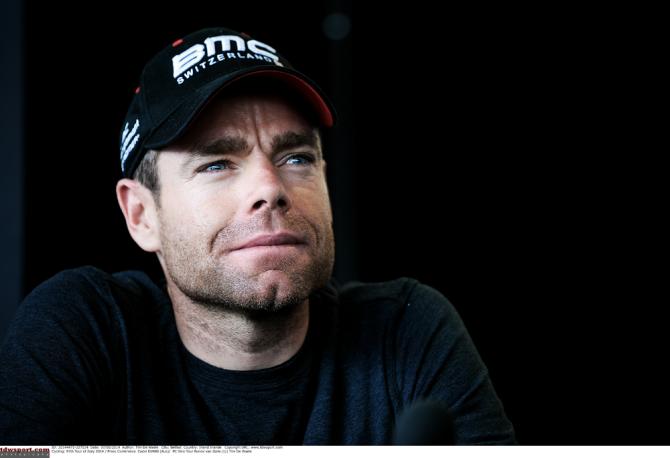

So what does he think he might miss the most? Evans, who after retiring from the sport will work as an ambassador for BMC bicycles, laughs before revealing:

"I'm not going to miss pressing the 'Set' button on my SRM."

Oh, there is also a private life to lead, too. Evans and his wife have an adopted son, Robel, whom he wants to spend more time cycling with and it seems that the feeling works both ways.

"My son asks: 'How many races have you got to do?' 'Why?' I ask. 'So I can ride with you on the weekends!'"

Rupert Guinness is a sports writer on The Sydney Morning Herald. He has covered cycling since 1984 and has reported on a total of 26 Tours de France since 1987

Rupert Guinness first wrote on cycling at the 1984 Victorian road titles in Australia from the finish line on a blustery and cold hilltop with a few dozen supporters. But since 1987, he has covered 26 Tours de France, as well as numerous editions of the Giro d'Italia, Vuelta a Espana, classics, world track and road titles and other races around the world, plus four Olympic Games (1992, 2000, 2008, 2012). He lived in Belgium and France from 1987 to 1995 writing for Winning Magazine and VeloNews, but now lives in Sydney as a sports writer for The Sydney Morning Herald (Fairfax Media) and contributor to Cyclingnews and select publications.

An author of 13 books, most of them on cycling, he can be seen in a Hawaiian shirt enjoying a drop of French rosé between competing in Ironman triathlons.