Boutique brands, Belgian beers and beautiful backdrops - Inside the bustling world of Colombian cycling

An experience of rough roads, high altitude, handmade bikes, handmade clothes, and Belgian beers

My interests, as they relate to bikes, are all about adventure. Going places and experiencing them in a way that's only possible on two wheels. That's a relationship that doesn't change even when I think about professional cycling. Sure, there's a whole layer of personal drama and team dynamics where the best cyclists in the world fight it out on a grand stage, but that's not all there is. There's also a back story about how those people became great.

One of those backstories, which we've heard a number of times through the years, is about climbing the mountains in Colombia. What's fascinating about that storyline is that it’s very easy for all of us, and especially Americans, to take part in. We can write our own chapter and experience the adventure ourselves. For me, that's the most exciting part and late this summer, I got to do exactly that.

I didn't do it alone though. I went to Colombia to pick up a custom steel gravel bike built by a company called Scarab Cycles and experience Colombian cycling while there. The people behind the brand showed me the roads they love and told me about the history they knew. I got a glimpse into the backstory of the brand while eating arepas and drinking Belgian beer (I’ll explain). I also got to see the same passion behind handmade Colombian clothing brand Safetti cycling and experience the city of Medellin on foot.

If you've ever thought about heading to Colombia and seeing if the rumours you heard about the climbing were true, they are, and this is my experience.

The setup

My adventure started by connecting with Scarab Cycles about Colombia. Scarab makes custom steel bikes that tell the story of their home country. The brand has options for both road and mountain bikes, but it's the gravel bikes I'd heard the most about. I'd seen one of the special editions at the Enve custom bike show and again at the Made show in Portland so I reached out and we started talking.

Scarab doesn't represent the whole of Colombian cycling and that's not the point. The brand sits in a small town roughly 45-minutes south of Medellín. As you head out the front door of the shop you'll find yourself right in the middle of the northwestern edge of the Andes Mountains with climbing in every direction. Some of those climbs are paved but many are not and all of them are steep.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Whatever you end up doing, you have to understand that there is basically no flat riding. You are either heading up or down. For Scarab, and by extension for me, it’s the unpaved roads that hold the intrigue.

As part of this initial planning stage, we talked about a bike. The idea was to fully immerse myself in the culture through the eyes of Scarab but also to take some of that culture back home and experience it in my own environment. While I didn’t know it at the time, it turns out the two could really use different bikes. I ended up building a bike for home and found myself underbiking in Colombia.

In the time leading up to the flight to Medellín, I spoke to the founders; Santiago Toro about the geometry and conceptual nature of the bikes and Alejandro Bustamante about the visual designs. On the mechanical side I wanted to stay fast, stiff, and light and chose to ride the Apuna allroad bike but go up in tyre size to a 700x40mm. I also chose each component based on my preferences.

On the visual side, every bike tells a story of Colombia and I wanted to make that unique to me as well. My family has a tree frog and my son loves them so when I learned the Golden Poison Dart Frog is native to the Pacific Coastal region of Colombia it provided the perfect bridge. I drew a frog and chose a colour from the Scarab palette that matched the frog’s colouring. Aside from that, I asked to add a bit more of the darker contrast colour to the areas of the bike that get the dirtiest. Like any customer, Scarab walked me through every piece of this process.

As I headed to the airport, the bike was waiting at the Scarab workshop and it was only a matter of getting there. I flew from the Pacific Northwest to Miami then onto Medellín. After landing I headed to a car and made my way south past El Café de Rigo owned by Rigoberto Urán. As an American, this sort of cultural deference to cycling is unheard of and I knew I was in for something unique.

The first ride

I wanted to maximise my time in Colombia so I opted for a red eye flight. Unfortunately this was not going to be the kind of smooth red eye where you fall asleep when the plane leaves then wake up when it's landing. I had two stops with layovers and the whole thing took close to 24-hours by the time I arrived at the Scarab factory.

Despite that, I stepped into the shop and right away I wanted to get out on the bike. One of the advantages of a custom bike is that everything fits exactly the way that you want it to without any adjustment. I'd given all my measurements and specified every detail of the build so there was no need to make any changes. All I had to do was change and the plan was to do a short gravel ride then meet at Scarab owner Santiago Toro's house for dinner.

As our small group headed out of the parking lot, it was first on a paved road. The roads were narrow and mostly lacked a meaningful shoulder but, as I've found in other countries, drivers are more courteous than I experience at home. Like in the Czech Republic, drivers tended to treat cyclists more like road users. No one cuts a wide swath into the other lane but there was also no one intentionally close passing.

I found Colombia had another dimension to the roads as well. While there were certainly plenty of cars and trucks on the roads, there were also lots of motorcycles and plenty of bikes. Despite narrow, twisty, roads, drivers regularly split the road into three lanes for passing, or allowing a pass, of smaller road users. My observation is that while I wouldn't expect wide shoulders, drivers in Colombia treat cyclists well enough that you can feel safe.

Of course all of this was going on in my head while I was also managing group dynamics with a new group, a brand new bike, and steep climbing. It was a lot to think about but I kept my eyes and ears open and the Scarab Apuna I was on was a perfect climbing bike. I had energy to spare and I was attacking the hills. In short, I was having a blast.

Then we turned off the pavement and I went from the front to the back. The roads were seriously rough and my limited technical riding skills were no match. I bounced around from rock to rock and often found myself walking hills so steep and technical that I was nervous about falling over trying to dodge rocks. This was especially true near where we peaked and turned around when the gradients were between 19 and 25%.

The payoff to the steep climbs was absolutely incredible views. Each time we had a moment to breathe, a glance to the left or right was breathtaking. Steep lush, green, mountains as far as the eye could see and a late afternoon sun over avocado fields is the kind of Colombian landscape you imagine. In person it's even more impressive.

Eventually, despite my urging, we turned around and headed back for dinner. We reached Toro's house just as the sun set and after a quick change, it was time for traditional Colombian food. I didn’t catch all the names but there were arepas and guava paste candies, both of which made repeated appearances throughout the trip.

Looking back on it now, I'd call that first day the purest Columbian experience of the whole trip. Steep paved climbs in traffic are common and so are steep and technical climbing and descending off road. In both cases, they will come paired with beautiful views and there's always arepas and guava paste candies at the end.

The bike company

I haven't done an exhaustive search to find every Colombian based frame builder but it's not that important to this story. Scarab is looking to do things a bit different than your average small frame builder. While the brand is certainly small, the processes are there to support scaling. Although I discussed it a little bit above, the frames are custom to you but it's very much a guided process with specific models and a specific design style. In short, Scarab is talking to an international audience and offering a product that is both unique to you and unique to Colombia.

Every bike that Scarab produces tells the story of Colombia and it's an opportunity for you to experience that story wherever you are in the world. That means you don't have to go to Colombia to pick up your Scarab. The brand will ship your bike to you wherever you are. If you have the opportunity to do it though, you'll have memories with a bike in a way that just isn't possible otherwise. In my case, I was doing more than just creating memories. That was a part of it but I also wanted to dig deep into who the people behind Scarab are.

Scarab is a partnership with three pillars. Santiago Toro is the founder, experienced frame builder and engineer, while Alejandro Bustamante is the artist directing all visual creative. There is also a board of directors whose passion for cycling and Colombian entrepreneurship helps to steer the business. Each piece is passionate about the business in a different way and no one is more important than the other. I spent the most time with Bustamante though.

Bustamante ferried our little group around in his first generation Chevrolet Trooper and we talked at length about his artist's journey. Bustamante had his training in architecture and had spent time in Europe learning and working. In terms of cycling, he had a passing interest over the years. Sometimes commuting and sometimes racing but things changed when he walked into a random small shop asking about further upgrades. The owner showed him that if he wanted to take the bike farther, he'd need to modify the fork. The idea that you could modify a bike was an eye opener. As we talked, I asked him if it changed his life and he said "yes."

Today, Bustamante is an adventurer, a strong rider, and a problem solver. The day to day work of Scarab is all about solving visual problems for customers. People have varying degrees of expertise and focus when it comes to the way their bike is going to look and he helps them put those pieces together. He's also on an artist's journey.

Scarab is famous for beautiful limited edition designs that tell very specific stories about Colombia. Some of them tell the story of the landscape, one tells the story of a journey Bustamante took by bike, there's one that reflects the art of the famous Chiva buses of Colombia, and the latest is an exploration of the Scarab beetle to celebrate the Scarab 5th anniversary. That latest one is a partnership with a local artist as are some of the others as well. More importantly though, they are all part of Bustamante's artist journey.

It's something I can identify with as a commercial artist myself but if you are less familiar, it's a very common arc. The specifics are different for every artist and every type of art but each time, it's an exploration of an idea. Once finished, you see what can change and you explore a new direction. Each leads to the next and for Bustamante, it wasn't so different. He talked to me about wanting to try a minimal look, then a more minimal look, then a maximal look, then we had another beer and celebrated taking a brief moment to enjoy the current design.

Toro, on the other hand, is an engineer. His process was more of a mystery to me but one thing I heard echoed was the desire to solve problems. For Toro the problems aren't visual but rather concepts of how to make the best handling bike possible and how to ensure that every bike is perfectly square and repeatable. His eyes lit up talking about the refinement of the jig the brand uses. I'll be honest that it's somewhat foreign to me and my background but I can tell you that it works. The workmanship is impeccable and the handling sublime.

The clothing company

I hedged my bet by saying I didn't do an exhaustive search for Colombian bikes. The truth is that I did look and didn't find many. Colombian cycling clothing is a different story. There are a lot of options. The brand I spent time with was Safetti.

Primarily that's because the man who founded Safetti, Federico Velez, lives not far from Scarab and owns a house that he rents out to tourists. In fact, these days he says he spends more time thinking about the house, and multi-sport training, than he does running the company. Instead he says that his wife takes care of the business and on the day I made my way to the Safetti headquarters in Medellín, that's who showed us around.

What I found most exciting wasn't who was in charge but the scale of manufacturing that existed under the roof of the company. American companies that both design and manufacture clothes under the same roof are non-existent. In contrast, Safetti employs hundreds of people who hand stitch exquisite clothes a few feet from where others design them.

Also, like Scarab bikes, Safetti clothes tell a Colombian story. Many of the designs look back to an older time in cycling. If that's not your style, the modern designs use a colour pallet and design details that feel straight from Colombia. You might also notice that the prices are lower than expected. At least in the US, exchange rates are favourable but the quality is as good as any brand you might have more experience with. I spent time riding in the Uncover Gravel Short Sleeve Jersey and Gravel bib shorts and felt right at home.

The other rides

I had the opportunity to do two other rides while in Colombia. The first was a classic coffee tour that perfectly mixed tourism and riding. The landscape was a bit less rugged than the first ride, but only slightly. The roads were mostly rideable but still very steep and the high altitude is always a factor as well.

For me, the highlight of this ride was drinking Coca-cola from a tiny shop at the top of a steep climb. I found myself feeling rather shattered and almost missed a turn but Bustamante, from Scarab, waved me back. Turns out a few of us had gotten separated so we debated having a beer while we waited but I opted for the soda instead. As I stood there and got some strength back, I knew it wasn't going to be a moment I forgot anytime soon. That wasn't the destination of the ride though.

Instead, we started the descent until eventually finding our way to a coffee plantation closer to the valley floor. We had more soda but also a chicken stew as well as fresh hand-roasted coffee at a place called Café Finca El Reposo. Like all the coffee I experienced in Colombia, it was floral and tart owing to the high altitude we were at. The experience of having someone roast it in front of you and then brew it with a French press transcends the actual details of the coffee though. When we were ready to continue on, it was time for a 10-mile / 16 km climb and a bit of warm rain.

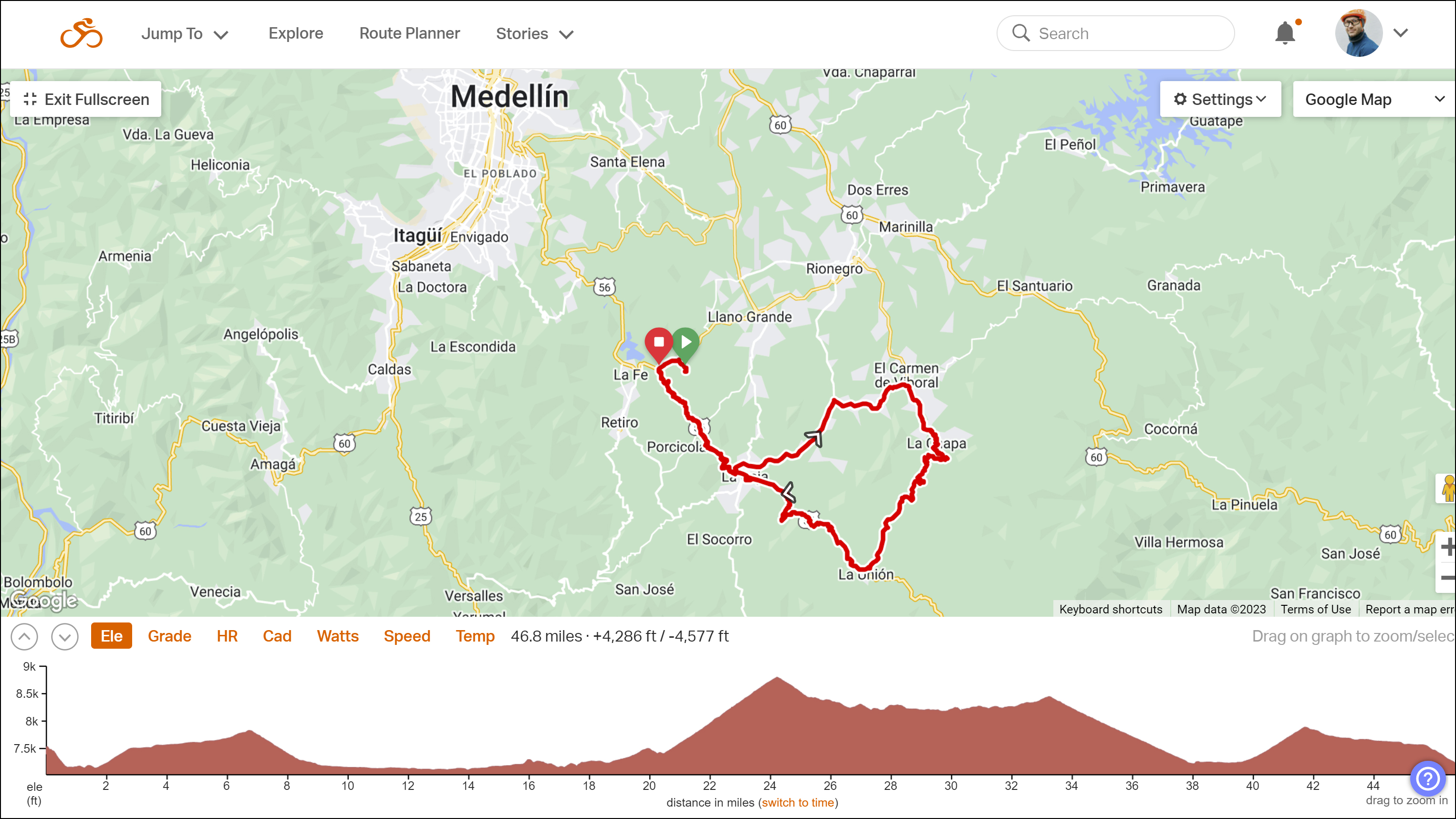

The last ride of the trip was the best match for the all-road Apuna I was on. Almost the entire ride was still either climbing or descending but a good portion of it had pavement. The off-road section was far less rough too. As usual, I found myself alone on the long gravel climb somewhere between the fast group and the slow group. This time though, it wasn't the mid-ride orange soda that stands out as memorable but the Belgium beer at the end.

Next to the Scarab factory is TorreAlta Cervecería. This "Belgian Inspired Craft Brewery in El Retiro, Colombia" is an excellent place for a post-ride beverage. There's outdoor seating, good food, and a Belgian Double in the late afternoon sun near the equator is a perfect way to end multiple days of hard riding.

At that moment, I never wanted to leave.

Josh hails from the Pacific Northwest of the United States but would prefer riding through the desert than the rain. He will happily talk for hours about the minutiae of cycling tech but also has an understanding that most people just want things to work. He is a road cyclist at heart and doesn't care much if those roads are paved, dirt, or digital. Although he rarely races, if you ask him to ride from sunrise to sunset the answer will be yes. Height: 5'9" Weight: 140 lb. Rides: Salsa Warbird, Cannondale CAAD9, Enve Melee, Look 795 Blade RS, Priority Continuum Onyx