Bondone brutality: Bahamontes, Gaul, and the 1956 Giro d'Italia's wildest day

Extract from 'The Eagle of Toledo' on a day that 'surpassed anything seen before in terms of pain, suffering and difficulty'

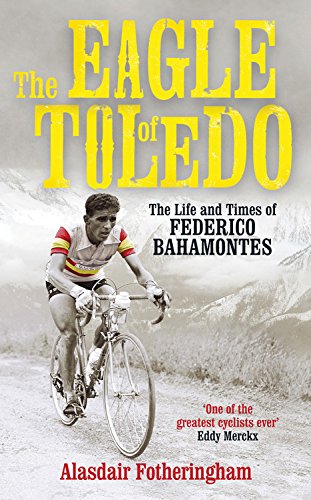

The following is an extract from 'The Eagle of Toledo: The Life and Times of Federico Bahamontes' by Alasdair Fotheringham, published by Aurum Press.

Stage 18 of the 2020 Giro d'Italia, were it to be taking place as planned on Wednesday, would be taking the riders up the mighty Monte Bondone ahead of the finish at Madonna di Campiglio.

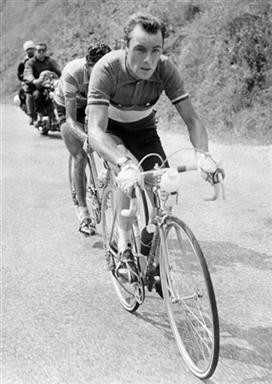

Bondone was immortalised at the 1956 Giro d'Italia as Charly Gaul ploughed through the most extreme of conditions to win alone and take the maglia rosa from further back than anyone else before or since. Bahamontes was a big rival of Gaul's back then, and this extract explores their relationship before delving into 'a day that surpassed anything seen before in terms of pain, suffering and difficulty'.

As a racer, Gaul was the complete opposite to Bahamontes in many ways: while Bahamontes was most effective in warm weather, Gaul seemed to come alive whenever the temperature dropped and the heavens opened. It was his ability to blast away in the coldest, most miserable of conditions that enabled Gaul to win both the 1956 Giro d’Italia and the 1958 Tour.

He is most famous in France for the attack in a rainstorm across the Chartreuse mountains that regained 14 minutes on race leader Geminiani. Only the national team system, which put the rider from little Luxembourg at a distinct disadvantage, probably prevented him from winning more.

There could be no doubting Gaul’s genius at breaking away whenever the roads steepened. Geminiani called the former abattoir worker ‘a murderous climber’. French writer Antoine Blondin, perhaps the greatest of cycling journalists, described him as ‘Mozart on two wheels’.

"When we raced we were irreconcilable," Bahamontes told me when Gaul died in 2005. "Going uphill even he admitted I was better, but when it rained he was impossible to beat."

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

But for all his affinity to Gaul, Bahamontes was kept at a distance like everybody else. "Charly was friendly enough," recalls Robinson, "but you could never get close to him, never really get to know him." And where Bahamontes was outspoken and fiery, Gaul was gloomy and withdrawn.

"He gives the impression that an evil deity has forced him into a cursed profession," commented one writer.

Teammates had the same problem with trying to get to know Bahamontes, which meant he received scant sympathy when things went wrong as they so often did in 1950s stage racing. It was a risky policy on Bahamontes’ part. As his knee injury proved the year before, nobody could be sure they would not need a helping hand. In Bahamontes’ case, his physiognomy meant he had to depend on teammates.

According to Ruiz: "Bahamontes always had one or two days where he’d have a sudden physical crisis, and depending on the terrain, he’d either be able to get over that crisis or not."

Known as ‘the bonk’ in British cycling circles, this sudden loss of energy is due to a rapid depletion of glycogen stores in the muscles. In Spanish it was called una crisis, or, more poetically, una visita del hombre del mazo, a visit by the man with a mace.

"On the stage to Vitoria [in the 1965 Vuelta] he started to claim his brakes weren’t working properly and he had punctures," says Ruiz. "That was why he had to stop on La Herrera, not for punctures. I had to stay with him to help him get there, using whatever means necessary, but I’m not going to tell you how."

Another member of Bahamontes’ team is not so reticent on how this was probably achieved. "He’d jam his arm between your elbow and you’d drag him alongside you," says Jimenez Quiles.

Like so many climbers, Bahamontes lacked the technical skills for weaving his way through the bunch and relied on a ‘sherpa’ to guide him. He would also need help regaining time lose on the downhill sections.

"He and Charly Gaul had this thing in their legs so that whenever we got to the mountains it was ‘goodbye boys, we’re off now’," says Robinson. "But Bahamontes was a bad descender, even worse than Gaul. And they’d both trail around the back quite a lot. I can’t remember Bahamontes doing a turn on the front. That’s not the way to race and that limited the damage both could do."

That legendary Giro stage

Eighty-three riders started stage 18 of the Giro d’Italia in 1956; forty-two finished.

One photograph sums up what they had to endure that day. It shows the previous year’s winner, the Italian Fiorenzo Magni, halfway up one of the stage’s five major cols. At that point, it is snowing lightly. But in weather conditions still rated as the most extreme in the race’s history, Magni will also have to battle through hailstorms, torrential rain and blizzards for nine hours and 242 kilometres.

With behaviour that seems to border on the lunatic, Magni – who has been riding with a broken collarbone since stage 12 – has the end of one length of inner tube from his tyres clenched between his teeth and the other wrapped around his handlebars. He is trying to use the minuscule additional leverage he receives by pulling with the inner tube both to keep the front half of his bike as high out of the snow as possible and reduce the pain in his shoulder to a minimum.

For Magni to have reached the point where he is reduced to such painful measures just to keep going epitomises the extremes to which the participants were pushed on this stage. The exit of Nino de Filippis, the provisional leader, was one of the most memorable: with his fingers glued around the handlebars with cold, and having ridden himself to a standstill, he and his bike simply keeled over in unison.

Magni, however, made it through. He finished third just 12 minutes down on stage winner Charly Gaul, who also moved into the race lead. Bahamontes would have moved into top spot overall had he stayed with Magni. But around 50 kilometres from the finish, and the final ascent to the Bondone, Bahamontes abandoned. He then had to make his way through snow and freezing fog to the nearest farmhouse to seek shelter.

"It was impossible to race. There had been landslides and stones as big as a cupboard were all over the road,” Bahamontes recalls. "Charly Gaul ended up partially deformed by the cold and I had frostbite in my hands and feet. I couldn’t use them properly for a month."

As winds reached speeds of 70kph, riders plunged their hands into bowls of warm water supplied by nearby inhabitants or downed glass after glass of brandy to try and regain some energy. Gaul was reduced to descending at a snail’s pace because his fingers could not pull on the brakes. When he reached the finish he was trembling so violently his clothes had to be cut from him.

"I’d never known such bad weather. It was really frightening," Bahamontes continues. "We just stopped wherever we could, two here, six there, wherever you were you abandoned."

Bahamontes asserts that "nobody got to the top on a bike", which is untrue of Gaul. However, his claims that a large number of the ‘finishers’ that day reached the line by car, has been corroborated.

“Me and [fellow Spaniard] Jesus Galdeano sneaked into somebody’s house and put on some pajamas we saw lying about," he says. "Finally we were picked up by a lorry. We all quit. Anybody who says the opposite is lying because then they came by the hotels the next day asking who wanted to finish the Giro. But I hadn’t reached the finish line so I wasn’t starting."

While he now says it was the extreme cold that caused him to abandon, in a profile of Bahamontes’ career cycling historian Javier Bodegas claims that was not the case.

Rather, Bahamontes roundly blamed his sports director at the Giradengo-ICEP team for his race’s premature end, saying he had sold out to Gaul and had deliberately driven ahead of Bahamontes in his team car on the ascent of the Bondone. There were also reports that when Bahamontes saw what had happened to De Filippis, falling like a deadweight on to the road, he was so frightened he stopped instantly.

Whatever really happened, Bahamontes would surely have led the Giro had he finished the stage, and then gone on to become the first Spanish winner.

He had started just six minutes down on the leader and 10 minutes ahead of Gaul. Instead, Gaul, his face wrinkled with cold, his hands and feet blue, gained a seven-minute advantage on his nearest pursuer, Alessandro Fantini.

"Charly has the skin of a hippo," remarked Geminiani; El Mundo Deportivo called the stage ‘a hecatomb’, slaughter on a large scale.

Gaul’s epic ride also brought him the record for overturning the largest overall disadvantage in the Giro to take the leader’s jersey. It is a feat that, more than half a century on, no one has matched. Meanwhile, Spain’s first winner of the Giro was not Federico Bahamontes in 1956, but Miguel Indurain in 1992.

'The Eagle of Toledo: The Life and Times of Federico Bahamontes' by Alasdair Fotheringham is available to purchase here.

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.