Biological Passport: Have dopers found ways to beat it?

Procycling investigates the cracks that have appeared in the tool credited with cleaning up cycling

The Athlete Biological Passport is more than 10 years old, and credited for cleaning up cycling. But the Aderlass scandal suggests athletes have found ways to beat it. Procycling investigates…

This article first appeared in Procycling magazine issue 258, August 2019

"We are dealing with one of the world's biggest doping scandals. There will come new insights. We have not reached the end yet."

These are the words of Lars Mortsiefer, a member of Germany's anti-doping agency, at his country's recent anti-doping conference in Berlin.

Mortsiefer's warning arose from questions about Operation Aderlass ('bloodletting' in English) – the Austrian Federal Criminal Police Office's eight-year undercover doping investigation that became public in February this year when investigators raided sites in Austria and Germany.

Aderlass led to the online outing of Austrian skier Max Hauke, filmed with a blood bag connected to his arm at the cross-country skiing world championships in Seefeld, Austria, and the arrest in Erfurt, Germany, of the physician Mark Schmidt, formerly a team doctor for the Gerolsteiner and Milram cycling teams.

The subsequent confessions of Stefan Denifl and Georg Preidler, plus the provisional suspensions of Kristijan Koren and Kristijan Ðurasek, and former riders Alessandro Petacchi and Borut Bozic, suggest Mortsiefer's proclamations aren't hyperbole. Aderlass looks set to be cycling's biggest scandal since Operación Puerto in 2006.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

It raised a crucial question: where was anti-doping's lauded weapon, the biological blood passport, in all of this?

An indirect jury

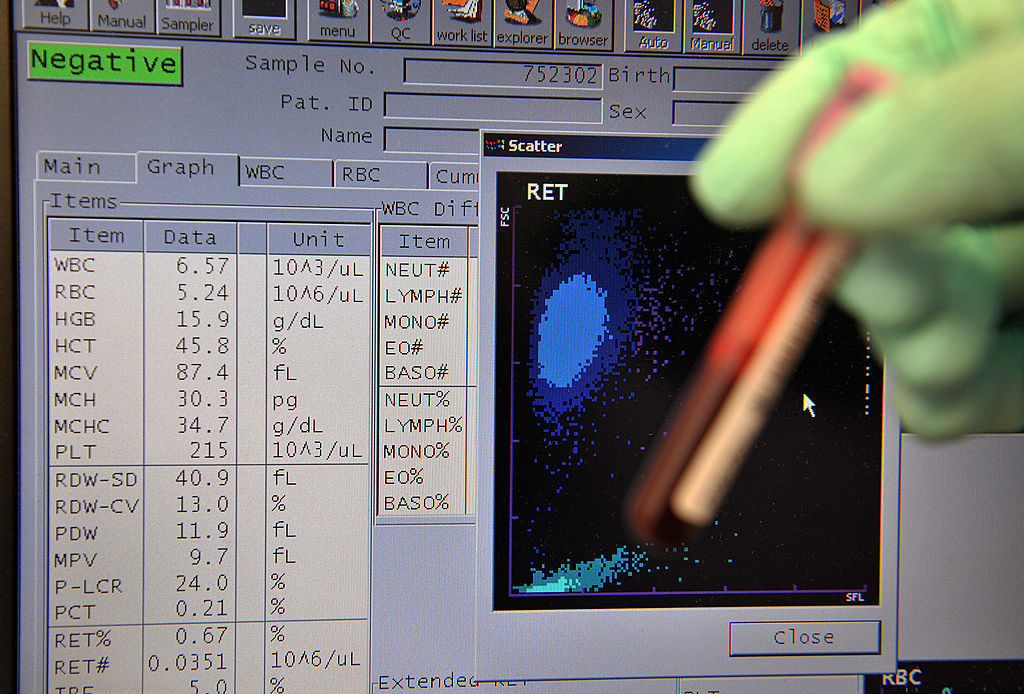

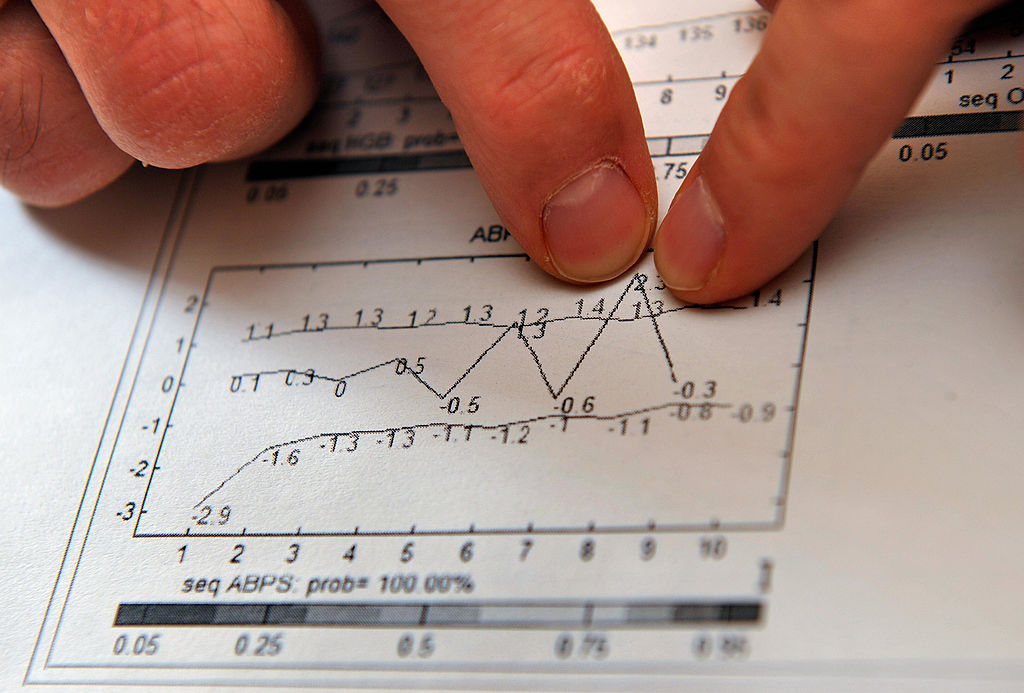

Cycling was the first sport to introduce the Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) in 2008. The previous system focused on banned substances: the level and type of drugs like erythropoietin (EPO) in urine, for instance. But the passport focused on fluctuations in indirect markers of drug abuse over time, the idea being that anomalies and trends would identify and catch cheats.

The WADA-funded ABP monitors myriad urine and blood biological variables, including reticulocyte and haemoglobin levels. A reticulocyte is a new red blood cell. Injecting EPO stimulates the body to produce more reticulocytes, increasing their total percentage.

The other primary method of doping, blood transfusion, requires the removal of blood before re-infusion. That initial drop stimulates the body to compensate by making more red blood cells, again leading to a higher-than-normal percentage of reticulocytes.

This is where things become complicated and where the ABP comes in.

"While reticulocytes skew upwards after doping, when you re-infuse your blood [with the blood you stored in the fridge], your actual percentage of reticulocytes then drops because the 'older' blood effectively dilutes the new blood," says Professor Chris Cooper, the biochemist author of the book Run, Swim, Throw, Cheat. "So the ABP picks up if there are unusually high and low reticulocyte levels."

Haemoglobin, on the other hand, plummets when you first extract blood but increases on re-infusion. Comparing the ratio of haemoglobin to reticulocytes gives something called the OFF-score, which picks up both the withdrawal of blood (a rise in reticulocytes and drop in haemoglobin levels), as well as the re-infusion of blood (a fall in reticulocytes and rise in haemoglobin levels).

Haematological scientists have observed that most people have reticulocyte percentages in their blood of between 0.5 and 1.5 per cent. Some are naturally higher or lower, but it's the spikes or drops that the testers are looking for. Though not 100 per cent proof, it's created a more stringent system.

"In the past it was far too easy to mask abuse," says Cooper. "I'd say it's much more difficult now."

The stats don't stack up

Or is it?

In 2017, research by University of Tübingen professor Rolf Ulrich found that 34 per cent of 1,800 elite competitors who completed an anonymous survey admitted to doping in the previous 12 months.

Ulrich quizzed athletes at the 2011 Athletics World Championships and the Pan-Arab Games, but the research – commissioned and funded by WADA – took six years to be published. What caused the delay? WADA cited issues with the author’s methodologies; Ulrich countered that the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), stakeholders of WADA, had blocked it.

Either way, this doesn't align with 2018's unpublished test statistics from the Cycling Anti-Doping Foundation (CADF), the independent body that manages the UCI's anti-doping programme. The CADF performed 10,405 tests, of which 4,701 were part of the biological passport with the remaining urine and blood samples direct tests for performance-enhancing drugs.

From those figures, 22 riders were sanctioned based on abnormalities detected in their ABP. That's significantly less than the 34 per cent cited by Ulrich. Yes, it's athletics not cycling, but elite endurance athletes are arguably constructed from the same DNA, both mentally and physically.

WADA defended the efficacy of the ABP in catching cheats, either directly or via subsequent target testing when values looked suspicious.

"For EPO targeting, the haematological module is estimated to have led to more than 350 positives [in all sports] above the rate prior to the introduction of the ABP," explains WADA's media relations manager, Maggie Durand.

"As regards the athletes implicated in the Aderlass investigation, of all those who had ABP blood tests – four did not – all but one were flagged by the ABP as atypical. The one who was not flagged had only four tests over the last six years. The ABP provides longitudinal information. However, it's important to understand that this information is not continuous. We only see when we test."

That, according to Sunweb manager Iwan Spekenbrink, is a flaw of the ABP.

"It's worrying that the police discovered this problem. It's why we must increase the number of ABP and direct tests, and it must be funded by the stakeholders of our sport," the Dutchman tells Procycling.

"We must influence a rider's behaviour. I'll give you an example: someone who drives at 100mph on the highway will drive slower if you put a radar every 100m. I know people argue about a rider's privacy but it's a price worth paying."

Current levels of testing vary by rider and role in the team.

"I'm hardly ever tested – maybe six to eight times a year, max," says Lotto Soudal's domestique, Adam Hansen.

It was a different story for Greg Henderson, the former sprinter and lead-out man, who also rode for the Belgian team between 2012-16.

"I'd be tested 26 times a year, minimum. Leading into big races, I was tested twice weekly."

The discrepancy in testing frequency is because the UCI targets the top three on a stage, plus three other riders picked at random. GC challengers are also targeted, although every rider must be tested just once per quarter. The ABP is reliant on long-term trends, meaning statistical accuracy. It demands data, and lots of it. Testing some riders four times a year simply becomes a needle in a haematological haystack.

Out-of-competition hotspots

It's noteworthy that CADF's latest figures show out-of-competition, both for the ABP and direct tests, is over twice the number of in-competition tests – 7,015 to 3,390. That's important, and why is highlighted by a landmark 2012 anti-doping study by Carsten Lundby of Zurich University. Lundby examined rider confessions and diaries to detail a common blood-doping strategy implemented by a rider aiming to peak at Paris-Nice in March, a spring Classic in late April and the Tour in July.

He wrote: "EPO would be abused in December to February to increase red blood cell mass. Once sufficient red blood cells had been synthesised, one to three bags of 450ml blood were withdrawn and stored for later use.

"One to two days before Paris-Nice, two blood bags would be infused and there'll be likely no trace of EPO in blood or urine at this point. Once the race is completed, the two blood bags will be withdrawn, stored and re-infused one to two days before the spring Classic and stored upon completion of the race.

"EPO injections are likely to occur in May when no competitions are planned. Following two to three weeks of treatment, the gained blood is withdrawn and stored for later use. For the Tour de France in July, two blood bags are infused one to two days before the start, and then one blood bag is re-infused on the two rest days. Since there is no direct doping test for autologous blood doping, this makes the doper very difficult to detect during competition."

You might think this looks dated, but Aderlass showed that blood bags remain a relevant strategy. As, of course, does EPO, albeit at much lower levels than times gone by.

"Anecdotal evidence suggests that dosages have decreased from 100 international units per kilogram of body mass a decade ago, to 5-10 units," explains Jakob Mørkeberg, senior science manager at Anti Doping Denmark. So around 5-10 per cent of the Armstrong era.

"But administration is performed more frequently now, such as five or six times a week instead of one large dose per week. That's a smaller performance increase but still two per cent. It also reduces the detection period, though that depends on the type of EPO used."

Some experts believe that micro-dosing at 11pm leaves no anti-doping markers by six the next morning. Mørkeberg disputes this time frame but the fact a French lab recently made headlines for creating a test that detected micro-dosing for up to 48 hours instead of the current 24 hours, shows the difficulties WADA face.

The French test requires further validation. Meanwhile, numerous studies question the credibility of the ABP. Take 2011 research by anti-doping expert Michael Ashenden that saw him inject healthy volunteers twice weekly with EPO for up to 12 weeks.

The treatment resulted in a 10 per cent increase in haemoglobin mass, the equivalent of two bags of reinfused blood.

"But the ABP did not flag any suspicions of doping," said the study.

Lundby and his colleagues have seen similar results.

"We've manipulated blood volume via EPO injections and blood transfusions," the Dane told us. "We sent the results to WADA-accredited labs and they failed to detect misuse. WADA then threatened lawsuits and weren't very happy with us publishing the results."

Plasma-volume quagmire

The main aim for blood manipulators is to boost haemoglobin mass while maintaining haemoglobin values and reticulocyte percentages at levels that don’t set off alarm bells. The problem is some of the blood parameters used in the ABP are influenced by the plasma volume (mostly water, but some dissolved proteins, glucose and hormones) of the blood.

"There are many legal factors that affect plasma volume," explains Dr Jeroen Swart, medical director at UAE Team Emirates. "These include heat, illness and a heavy training load, which is what makes in-competition testing, especially stage races, so problematic.

"Altitude has a significant effect on plasma volume, too," Swart adds. "For example, a trip to 3,000m will result in a 15 per cent contraction of plasma volume. This is a significant change, which is why the question of altitude exposure is asked whenever a blood sample is collected.

"While reticulocyte percentage isn't measured against plasma volume, and therefore not affected by plasma volume changes, there are still changes that occur in response to altitude and on return to sea level. All of this makes altitude exposure a problematic factor in the bio passport."

The aim of micro-dosing is to illegally boost haemoglobin levels. The aim of altitude training is to legally boost haemoglobin levels. It's why there are concerns riders head to the latter and adopt the former.

"If you want to cheat, go to high altitude and explain your blood transfusion results as altitude training," Lundby warns. “It's why ABP is not a perfect system."

In Lundby's 2012 paper, he stated that altitude tests weren't taken into account due to how much they can skew figures.

"That’s changed," says Hansen. "Now when you go to altitude, you write it in your Whereabouts notes so WADA can calculate how high you are and observe how readings adapt to time and altitude. When I altitude train at home (tent and mask), I give a very clear explanation on the control forms."

But decoupling the effects of micro-dosing and altitude is difficult, made even harder by those altitude tents.

"You need to spend one month above 3,500m to increase red blood cells by five per cent," Lundby explains.

That's much higher than the likes of Teide and Sierra Nevada. You can see how sleeping low at home but training high is a popular combination for clean riders. You can also see how it would act as a doping mask.

Doping ingenuity

Sadly, that's not the last of the ABP's altitude woes.

Back to Lundby.

"When you're at altitude, you need a master regulator saying you need more EPO. In EPO's case, it's HIF-1 [hypoxia-inducible factor 1]. This degrades at sea level. However, there are drugs called prolyl hydroxylases that stabilise HIF-1. Take these and you can enjoy a constant source of HIF-1.

"It's brilliant for kidney patients, who it was developed for. But from an anti-doping perspective, it's a nightmare because you won't be able to distinguish whether the increase in EPO is artificial or not, unless you analyse for this specific compound. But the list of manufacturers of these is very long. It's an endless problem," said Lundby.

It's why experienced experts like Lundby are, in the words of the Dane, "less enthused than when I started".

Still, the war continues. To that end, all the experts and riders interviewed for this piece stated that the ABP has had a positive impact on the professional peloton, be it through capture or as a deterrent.

They also agree that the ABP should be one part of the anti-doping jigsaw. Whistleblowers, like a key witness in the unfolding Aderlass scandal, cross-country skier Johannes Durr, are also integral. Then there's more targeted testing, via analysis of social media activity and the WADA-funded Athlete Passport Management Unit (APMU) approval process, which will be rolled out next year.

"We're also exploring the use of pattern classification tools (for instance, artificial intelligence) to improve the detection of certain anti-doping violations," adds WADA's Durand.

Then there is a gamut of innovative ideas including the power passport, or a test designed by Yannis Pitsiladis of Brighton University that detects changes in the expression of genes that are triggered by blood doping, such as transfusions or performance-enhancing drugs. The test, Pitsiladis tells us, even detects micro-dosing.

Swart is also playing a part.

"Our research unit at the University of Cape Town is looking at oculomotor deception testing. Effectively this is a lie detector test that measures ocular changes and can be performed by the doping control officer at intervals during the year.

"Overlaying this data on the biological passport may provide clarity on whether changes are related to confounding factors or to doping. This would aid in identifying where to allocate resources and to perform targeted testing."

And despite the dent to his anti-doping enthusiasm, Lundby is also working on two ideas: one that looks at iron metabolism, which is affected by blood manipulation, and by analysing haemoglobin mass itself.

"We've developed a blood-volume analyser, which can detect changes in volume of one per cent. That's good compared to the sensitivity of normal biological tests."

Mørkeberg supports Lundby's test, as haemoglobin mass isn't affected by factors like hydration and training state which influence ABP readings.

"The degree of uncertainty of whether changes are caused by doping or normal variability decreases," he says. If measuring haemoglobin mass becomes an anti-doping tool, it's evolving a past method.

"When I rode for T-Mobile in 2007, we could indirectly measure haemoglobin mass via a carbon monoxide re-breathing test," says Marco Pinotti, now head of performance at CCC Pro Team. "But it was never implemented by WADA."

Why that is might be down to its complex protocol, which requires breathing 100 per cent oxygen, taking blood samples, breathing in pure carbon monoxide and attaching catheters. Studies also suggest it underestimates values. Lundby's refined the idea, techniques and accuracy.

Lundby and his contemporaries have the ideas and the will is there, but the money isn't. There are 31 WADA-accredited laboratories around the world. Any new test requires independent verification, equipment and software for each of those labs, plus the experts to activate those tests. It's why, concludes Spekenbrink, more affordable anti-doping education must begin at youth level.

"But we must find the money for tests, tests, tests. Look at [Georg] Preidler. He raced for us for years [before moving to FDJ and admitting blood withdrawal in 2018]. He seemed like a normal guy. So it was a shock. If guys like him are doing it, it shows the challenge we have."

Anti-doping is much more sophisticated than it was five, 10 or 20 years ago. However, the cheats have also advanced at the same time. It looks like the sport will keep having to develop more methods to fight the dopers. Cycling has led the way, but it must continue to do so.

Procycling’s August 2020 issue is out to buy now, featuring 21 stories from the Tour de France, including interviews with Romain Bardet, Tejay van Gardren, Robbie McEwen, David Millar, Merharwi Kudus, Nicolas Roche, Michael Matthews and more.

Procycling magazine: the best writing and photography from inside the world's toughest sport. Pick up your copy now in all good newsagents and supermarkets, or get a Procycling print or digital subscription, and never miss an issue.

Follow @Procycling_mag on Twitter