Behind the scenes: How Cyclingnews reported on the Genevieve Jeanson story

Looking back on the troubled saga of the former Canadian star for Cyclingnews' 25th anniversary

“Andre always told me that he was going to commit suicide if I left him and that he would kill me and then he would kill himself. When I started taking EPO, he told me, 'If you say that to anyone I’m going to kill you.’” - Genevieve Jeanson - Exclusive Podcast, Cyclingnews, 2015

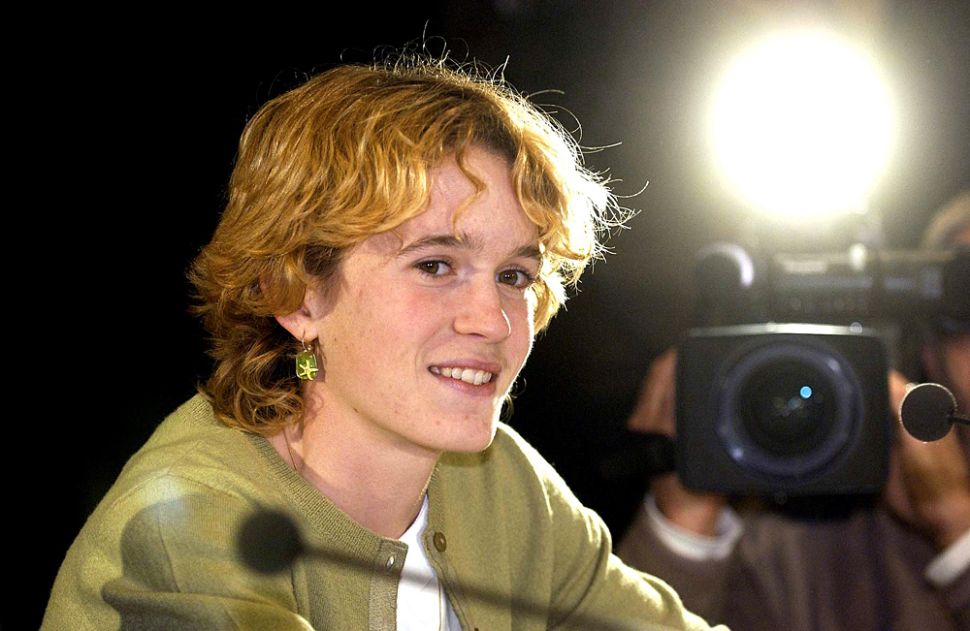

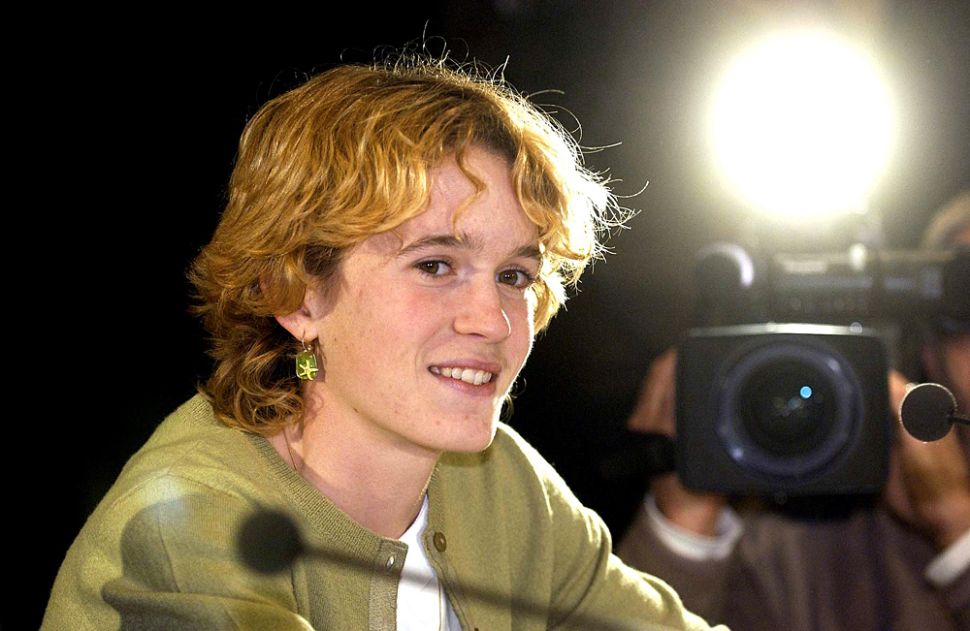

Genevieve Jeanson’s face stood out amongst the crowds of people watching the UCI Road World Championships in Richmond, Virginia, in September. The French Canadian is one of the most controversial figures to have come out of women’s cycling after she confessed in 2007 to using erythropoietin (EPO) during most of her career, beginning as a teenager in 1998 and through her early 20s until 2005. She was subsequently issued a reduced 10-year ban for cooperating with an investigation conducted by the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES) into her allegedly abusive coach Andre Aubut and Montreal-based physician Maurice Duquette.

Jeanson, now 34, sat down for an impromptu podcast discussion with Cyclingnews’ Kirsten Frattini, in what was her first English-speaking interview since her doping revelations. During the interview, Jeanson opened up about her relationship with Aubut and made serious allegations that prompted Cyclingnews to investigate further.

The process of establishing facts involved an extensive amount of research over the course of ten weeks. This included examining the history of Jeanson’s and Aubut’s coach-athlete relationship, their respective doping suspensions, following up with key sources and gathering statements to substantiate Jeanson’s allegations of abuse, which included a series of threats.

After the podcast discussion, Cyclingnews conducted four follow-up interviews with Jeanson, on September 28, October 1, October 31 and November 27, to establish timelines, and to develop a more complete understanding about her claims.

You can listen to and read the Genevieve Jeanson - Exclusive Podcast and feature story along with the Genevieve Jeanson: New questions and answers on Cyclingnews.

A complex abuse story

Jeanson agreed to speak with me in a one-on-one interview at the UCI Road World Championships in Richmond, Virginia, in 2015. I wasn't immediately sure how I would approach the conversation, what I was going to ask, or what parts of her story we would focus on. The interview was set up quickly and I found myself reviewing as much information as I could the night before our discussion. I needed to refresh my memory on the critical aspects of her story. I already had a well-informed understanding of how her professional cycling career rose and then fell between 1999 and 2007. I was either at a lot of these events or remembered reading about them over the years, but it had been more than ten years since I had seen her in person, and I had so many questions.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

I located old articles about her winning the time trial and the road race at the junior world championships in 1999 and how she astounded the cycling world with her victory at Flèche Wallonne the next year. I read about her debut at the 2000 Olympic Games and her national championship titles in 2003 and 2005. I watched her head-turning wins on the American scene at the Tour de Toona twice (2001 and 2005), Redlands Bicycle Classic twice (2001 and 2003) and Tour of the Gila three times (2001-2003), where she would often almost effortlessly ride away from the field. Her three victories at the Montreal World Cup launched her into celebrity status in her home province, Quebec.

I also read about the red flags: the alarmingly high 56 per cent hematocrit following a health check at the 2003 World Championships in Hamilton, the missed doping control at Flèche Wallonne in 2004, and ultimately her positive doping test for EPO at the Tour de Toona in 2005, and her lengthy denials. I watched her defiant confession about cheating while speaking with respected Canadian journalist Alain Gravel in his investigative report that aired on Enquête, a Radio-Canada television show, in September of 2007.

In Richmond, Jeanson and I met in the morning at the World Championships' headquarters and found a quiet place in the lobby next to a window that faced the finish line. We watched parts of the elite men's race as we spoke. It offered us both a chance to pause, reflect, and moments of brief distraction after the heavier aspects of our discussion – the abuse.

She described to me how she met Aubut during the summer of 1994. She was 13 years old, and he was a high school teacher that worked part-time during the summer at her local bike shop. Her parents consented to Aubut designing training plans for her the following year when she was 14 and wanted to take cycling more seriously.

She told me that she first took EPO in 1998 when she was a 16-year-old junior cyclist. She alleged that Aubut and Duquette, a local doctor, gave her the drug at an appointment that she attended with her father. She continued to use the drug for eight years until she tested positive for it in 2005. She said her parents knew about the doping but not about the physical violence.

Jeanson's abuse allegations were not new. After the Enquête interview aired in 2007, Gravel wrote L'affaire Jeanson: l'engrenage, a book that documented his interview process with her, and the steps it took for her to open up about her history with doping. It also detailed the unhealthy relationship between Jeanson and Aubut.

Up until that point, a lot of the conversations surrounding Jeanson's story focused on her doping violations. Those discussions were valid because athletes that choose to use banned substances take away from those who compete clean, and doping does a lot of damage to the sport.

In Jeanson's case, doping was a part of a bigger and more complex story of abuse. Jeanson wanted to tell her story, and I had questions; how did she get involved with an allegedly abusive coach at such a young age? How and why did a registered physician provide a minor with a potentially-dangerous banned substance? What was her parents' involvement? Did anyone try to intervene? These were individuals who were in a position of authority and trust concerning Jeanson.

This story dug deep into the fundamentals of ethics in sport concerning doping, abuse, and a disturbing coach-athlete relationship, along with the broader systems in place to protect athletes. It was a story that needed to be told in the English-language media and to the cycling world.

A lot happens behind the scenes with this type of journalism; it can be expensive and time-consuming and involves a lot of background work and questioning, re-questioning, and fact-checking. Stories of this nature are challenging to report on because abuse often happens behind closed doors, and it sometimes ends up being one person's word against another. Journalists have a responsibility to thoroughly, objectively and accurately question and investigate claims of abuse to get as close to the truth as possible. We have an equal responsibility not to publish baseless allegations. We also have an ethical responsibility to everyone involved in the story.

Investigative journalism also requires a certain level of support from the publishers. I was fortunate to have the approval to investigate Jeanson's claims from our Editor-in-Chief Daniel Benson, along with a tremendous amount of support and guidance from Katherine Conlon, who is the Director of Legal Affairs at Immediate Media, the publishing company that owned Cyclingnews in 2015.

Behind the scenes

Legal risks

There are legal risks involved in covering abuse stories, and the main one is defamation, the publishing of false statements about a person that harms or lowers their good reputation. Jeanson's allegations of verbal, physical and emotional abuse at the hands of Aubut could have crossed the threshold of defamation if not shown to be true. Katherine Conlon, Director of Legal Affairs at Immediate Media, helped us navigate the legal intricacies of reporting on Jeanson's story before publishing it in 2015. She said that judges in defamation claims would look for evidence that the publication and the journalist did the necessary, and often painstaking, background work to make sure the story was true well before publication.

"Under English law, in a criminal trial, if I believe that you have committed a theft, I have to prove that you did it beyond reasonable doubt. In a defamation claim, the burden of proof is reversed, and it's for the defendant [the publisher - ed.] to prove that the thing that they published was not defamatory on a balance of probabilities. There are various ways that you can do that, and the strongest, of course, is to prove that what you've said is true - things can't be defamatory if true."

One of the challenging aspects of covering Jeanson's story was that we needed to run a series of checks that satisfied defamation laws in three separate jurisdictions; the UK where Cyclingnews is published, Canada where Jeanson and the journalist (myself) resided, and the United States where Aubut lives. In doing so, we used defamation specialists in all three jurisdictions to ensure we properly reported Jeanson's allegations in a way that was legally compliant in the UK, Canada and the US.

"We decided that the best and safest way to make sure that this was done thoroughly and well was to layer into our English approach the additional measures required to be compliant with Canadian and US law," Conlon said. "There were distinct things that we were having to do to satisfy one jurisdiction or another."

The unavoidable fact, however, is that abuse often happens privately and there are limited witnesses to corroborate these kinds of allegations. It usually comes down to one person's word against another, making it challenging for journalists to report and law enforcement to prosecute. According to Conlon, our reporting of Jeanson's story needed to build a factual structure to support her allegations, and to some degree, her opinion, to show that it was honestly held and without malice.

"If you're making an abuse allegation it helps to show that they fit within a framework of behaviour, and that's what we were able to do," Conlon said. "There were allegations that she made about things that happened between [herself and Aubut] that neither we nor anyone else was privy to. We could pick out other facts that she told us, such as, a threat Aubut made to burn down her restaurant in front of a witness, teammates who had seen him throw things at her, and people who had heard him shout terrible things at her. We gathered together statements from those people because it drew a picture that meant the story didn't hang only on the allegations about what happened behind closed doors. The things that he had done to her in public were bad enough."

Public importance

There's the term "public interest" that journalists and publications often use to justify our coverage of abuse stories in sport, but what does that mean? The Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO) code defines public interest as including but not confined to "detecting and exposing crime, or the threat of crime, or serious impropriety; protecting public health or safety; protecting the public from being misled by an action or statement of an individual or organisation; disclosing a person or organisation's failure or likely failure to comply with any obligation to which they are subject; disclosing a miscarriage of justice; raising or contributing to a matter of public debate, including serious cases of impropriety, unethical conduct or incompetence concerning the public; disclosing concealment, or likely concealment, of any of the above."

However, the phrase can be misleading, and Conlon rightly pointed out that it doesn't mean "anything the public is interested in". When she addresses this concept with her editorial teams, she prefers to use the term "public importance".

"In the story that we reported, Genevieve was making allegations that touched on issues of criminality, potential abuse of medical qualifications and registration, a lack of safeguarding measures put in place by sport governing bodies, and the protection of young people in sport, and so it was undoubtedly of public importance."

There is a history of bullying and abuse in sports being treated as justifiable if it produced the right results, and Conlon hopes the tide is turning. Jeanson's story highlighted how the sporting system's treatment of young athletes was often unchecked and almost normalised, not just 20 years ago, when she began racing, but even today.

"However fit and bright and confident they might be, young sportspeople who move away from home during adolescence when most children would still be under the protection of their family, are unusually vulnerable to being swept into systems where the priority isn't necessarily their well-being but the results they can achieve," Conlon said.

Responsibility

There are many responsibilities to consider when covering abuse stories in sport, ethically, morally and legally, and juggling them can turn into a real balancing act.

Journalists are responsible for telling the most accurate story we can while our publication's legal team must protect the business from financial or reputational harm. There is also a legal responsibility not to put defamatory allegations into the public domain unless defensible, and so when navigating Jeanson's story, there were a number of ethical and legal considerations.

"Even the most appealing interviewee in the world may not be telling the truth," Conlon said. "The last thing you want to do is perpetuate a falsehood. So, there was a constant interplay here between what we felt the legal requirements were to tell this story properly and the kind of ethical responsibilities that we felt we had to have for everybody involved. We don't want to deepen someone's trauma by doubting them, but journalists need to thoroughly investigate serious allegations before we publish them."

After the initial one-on-one podcast interview with Jeanson at the World Championships, we scheduled four additional follow-up interviews over the phone because we needed to be thorough in our questioning her allegations. We had a responsibility to Jeanson to tell her story fairly and objectively. We also had to be transparent with her about our reporting process and a separate responsibility to give Aubut his 'right of reply' to the allegations.

"As an organisation we want to safeguard vulnerable people – vulnerability comes in different forms – and could include victims of abuse recounting their experiences. I think there's real importance in allowing people who have been victims of abuse to tell their story while also being even-handed and making sure that we're not printing baseless allegations," Conlon said.

The worst-case scenario

Defamation claims can lead to severe and expensive consequences for both the journalist and the publication. Therefore, when handling a story that includes allegations as serious as Jeanson's, it's essential to consider the worst-case scenario and work backwards. If this went to court – what would a judge think? Is our conduct when preparing the story for publication thorough, proper, and beyond reproach?

"My job is to figure out what the worst-case scenario is and prepare for it," Conlon said. "It's always better to do it from the beginning. In defamation claims, judges want to be sure that you did the thinking and the hard work of proving the story before you began to publish. Things travel so fast now on social media, and once you've made these allegations, there's no taking them back."

Conlon said that in her role as a media lawyer, she has to strike the right balance between considering the legal risks and protecting the business, while also allowing journalists to cover important stories, which the company pays them to do.

"I've always seen my role as being to try to empower journalists to do what they want to do but do it in a way that is ethical and with a measured amount of risk," Conlon said. "My decision is almost always shaped by; How risky is this? How can we manage the risk? After we've managed the risk, is there still a story worth telling?

"I strongly felt that if we did a good enough job, then [Jeanson’s story] would be a story worth telling. We put together a story that told her truth, but which at the same time, was told in such a way that wouldn't leave her or us further exposed."

Covering Jeanson's story meant conducting an investigation into her allegations, and investigative journalism is more costly than any other form of journalism. The work is also time-consuming, and according to Conlon, had to be justifiable internally, as not just the right thing to do morally but also not likely to ruin the business or its journalists' professional reputation.

"'Standing up' the story allowed senior stakeholders within the business to stand behind the reporting team with confidence," Conlon said. "We transcribed the interviews to make sure we all knew what material we were dealing with and engaged a French-English translator to work through the book about Jeanson, written by Alain Gravel, to check for discrepancies in her allegations."

Conlon added that we also received important support from the Board of Directors level.

Witness statements

A key aspect of reporting on Jeanson's story revolved around locating, interviewing and collecting witness statements. These statements came from individuals who could corroborate her abuse claims or provide evidence that allowed us to paint a picture and add context concerning Aubut's abusive, unpredictable, and angry behaviours in public.

"She was able to tell us about people who had witnessed the events which helped us to underpin her allegations. They had seen her shouted at, assaulted, they'd seen him throw things at her, so asking those contacts for their recollection helped to provide roots to support Jeanson's story and add credibility for her sake and ours," Conlon said.

We spoke with her former teammates Catherine Marsal and Amy Moore, along with Aubut's former co-director at the Rona cycling team, Jim Williams. All three witnessed Aubut's verbal abuse toward Jeanson and saw him throw objects at her. We conducted two additional interviews with individuals who wished to remain anonymous: a person who lived in proximity to Jeanson, who frequently saw bruises on her body, and a witness in the restaurant when Aubut threatened to burn it down.

We then asked the individuals we interviewed for this story to provide us with witness statements. These signed documents served several purposes. Conlon explained that they helped our witnesses understand the seriousness of our reporting. They provided a paper trail and confirmed we had not misunderstood their meaning and made it clear to them that this could have legal ramifications for them and us. The fact that they were content to sign these witness statements gave us additional confidence in our reporting of Jeanson's story.

"I didn't want the interviewees to think that this was trivial or something that we were taking lightly," Conlon said. "I wanted them to understand that we were telling this with true seriousness because that's only fair to Genevieve and Aubut. Asking someone to sign their name to a piece of paper giving a clear legal statement saying they believe they have given their most accurate recollections, and that their facts were true, meant that I had confidence in these people to stand by the things they had said.

"It's also another way of proving to an imaginary future judge that we did everything in the most rigorous way that was available to us."

Right of reply

An essential step in reporting on Jeanson's story was providing Aubut with his right to defend himself against her allegations. According to IPSO 1 (iii), "A fair opportunity to reply to significant inaccuracies should be given, when reasonably called for."

Journalists must consider offering the subject of criticism and allegations an interview and reflect their response fairly in the report, provide respondents with enough detail about the allegations to understand them, give an informed response, along with an adequate amount of time to respond.

"It's helpful from a legal perspective and gives us the best chance of making sure that what we're publishing is truthful, fair, objective and thorough," Conlon said.

Once we had located Aubut's contact information, we called and left several messages on his phone that outlined our purpose for calling and detailed Jeanson's allegations. When he did not respond to my messages, Daniel Benson called his phone and he answered, but only giving Benson enough time to state who he was and why he was calling, before Aubut hung up. We then used FedEx to send him a personal letter and had it tracked to be sure that it was received. We also built in additional time before publishing to give Aubut an adequate amount of time to understand the allegations thoroughly, seek legal advice (if he wanted), and provide his response. We also needed time to reconsider the story completely if his response gave us doubts. In the end, Aubut chose not to respond.

"We had to be able to give his side of the story, if he chose to share it with us, a proper airing, to potentially revisit the allegations and to provide his perspective. He chose not to provide it, " Conlon said.

"We can't read anything into that, but from our perspective, we knew that we were doing everything required of us by a court if this, at some point, went further. It showed that we were acting in the public interest and that this was a story of importance. We were allowing everyone involved to share their recollections and provide a truly balanced picture of what had happened."

Athletes operate within a system, not a vacuum

Jeanson's story has shown that there were limited systems to handle abuses in sport 20 years ago. It wasn't until recently as five years ago that sport governing bodies began implementing dedicated reporting pathways, creating harassment and abuse policy, and changing codes of ethics. Many now encompass not just the athlete but also sports personnel, staff, and anyone working with athletes.

Sport governing bodies are now taking a more proactive approach and are beginning to prioritize education and prevention. They are also moving toward conducting independent investigations upon receipt of an abuse complaint.

"Genevieve's story is horrific, but I also think about what may have allowed it to happen," said Kelsey Erickson (PhD), Executive Director of Athlete Health & Well-Being at USA Cycling. "I always find it interesting how shocked people are when they hear about these types of situations happening in sports. Sport is part of the world, and so we are not immune to misconduct. We have an obligation to educate athletes from a very young age about their rights and where they can report things and what they should be reporting. These situations rarely go from a super-healthy and appropriate coach-athlete relationship to something much worse overnight - there's usually stuff that happens inbetween. It's on us as organisations to educate athletes, parents and every other person involved in and around sport about what abuse looks like and misconduct in general.

"Her story continues through adulthood, and part of that is likely because she was young when the coach-athlete relationship began. Small questionable things probably occurred overtime and eventually evolved into her being a victim of horrific abuse. You justify and rationalise something here and there, and over time it often escalates. Plus, there is a significant level of trust that has developed at this point. Why question it? And it's important to recognise that it's not just young athletes who are abused – we also need to help our adult athletes recognise when they're being taken advantage of and when power imbalances are at play.

"One thing I've noticed in my role is that many people want to believe it's the odd bad apple, but it's more prevalent than people want to believe. Again though, that isn't unique to sports. It is more common in day to day life than people often recognize, and it also happens in sport. We don't have the luxury of playing naive, anyone involved in this space has to open their eyes and recognise that bad stuff happens, and we have to take responsibility to address that. We're involved in this space, and therefore, we have to educate ourselves and play a role in prevention."

Jeanson's account was very much a precursor to an ongoing wave of testimonies from women's cycling in the last five years. More and more athletes feel empowered to report and go on the record about the abuses and harassment they have experienced in the sport.

Two years ago, Volkrankt published allegations made by former riders against the owner of the women's team Cervelo-Bigla, Thomas Campana, accusing him of abusing his power as the head of the team in 2015. The alleged offenses included bullying, fat-shaming, intimidating riders, and ignoring medical concerns. According to that report, half the riders withdrew their formal complaints at the UCI Ethics Commission when they found out that their names would be public knowledge. The report noted that all the events in the indictment happened during an older version of the UCI Code of Ethics, that didn't include team managers. Therefore, he could not be held liable. Campana denied all accusations, and his team subsequently implemented athlete welfare measures, including an anonymous conflict resolution service from a qualified lawyer.

The UCI has made improvements and changes to the code, and, as of 2016, it now covers team management and staff. There is now 'anonymity of the plaintiff' to better protect the victim's privacy. There are dedicated reporting channels for filing complaints. Teams are now encouraged to identify a person of contact who has the right to collect information relating to situations of sexual harassment and abuse and take action with the UCI Ethics Commission on behalf of a team or rider.

Given her professional background, Erickson naturally compared the systems in place for anti-doping at the World-Anti Doping Agency (WADA) with those currently in place for abuse in sport. She said the latter has a lot of work to do to catch up.

"It's critical for policy to cover everyone in the sport, not just athletes," Erickson said. "I commonly compare the SafeSport landscape with that of anti-doping. Global anti-doping efforts have, thankfully, moved from recognising doping as an athlete-centred problem to understanding that athletes operate within a system. This same recognition is critically important within the SafeSport movement too. Not until we account for the system, will we be able to address doping or abuse effectively.

"We need to understand that athletes don't operate in a vacuum; many people and systems influence them from a very early age who have control and influence over what they think, do and, often, whether their career progresses."

Erickson said the current WADA code has changed to include more sanctions for sports personnel.

"Six out of the current ten anti-doping violations are relevant to athlete-sports personnel. We see that within the SafeSport context, we have to be able to account for those around athletes, including a broad range of people. Without that, we can't really change anything."

There has been testimony involving sexism and discrimination within cycling. In 2016, Jess Varnish, Nicole Cooke, Emma Pooley and Victoria Pendleton, all spoke out about a culture of discrimination and sexism at British Cycling. After an internal investigation, the sport governing body upheld one of the eight allegations that Varnish made against former technical director Shane Sutton.

There has also been an alarming number of riders who have given public testimonies specifically involving sexual abuse within cycling. Dutch cyclist Marijn de Vries detailed her experience with sexual assault by a soigneur in a blog post. Missy Erickson wrote about the abuse that she experienced as a junior athlete by an adult affiliated with her cycling club in Bicycling Magazine in 2017.

In the past year alone, the UCI Ethics Commission has opened new investigations into two Belgian women's teams: Health Mate-Cyclelive and Doltcini-Van Eyck. Riders from both teams filed formal complaints of abuses against their respective team owners, Patrick Van Gansen and Marc Bracke.

We first reported in June of 2019 that Health Mate-Cyclelive riders – Esther Meisels, Sara Mustonen and the father of Chloë Turblin – separately filed abuse complaints against Van Gansen with the Ethics Commission. All complaints centred around the UCI Code of Ethics: Appendix 1 that covers protection of physical and mental integrity – sexual harassment and abuse. In the wake of those reports, six more riders came forward to corroborate the allegations, in the Belgian press. A tenth rider wrote to us detailing an unsettling environment during her time with the team. An eleventh rider, who wished to remain anonymous, filed a fourth formal complaint with the Ethics Commission. Van Gansen denied all allegations. It took over a year for an independent investigation led by UK-based Sport Resolutions to come to an end and for the UCI to announce that Van Gansen had violated its Code of Ethics.

In March, the Ethics Commission opened its investigation into Doltcini-Van Eyck and Bracke after two riders – Sara Youmans and Marion Sicot – alleged Bracke requested photos of them in their "panties and bra" and "bikini". The UCI's investigation concerning these complaints is ongoing. Bracke denied the allegations and said that he requested images of riders' legs for professional reasons only.

In a separate case, a third rider from the same team, Maggie Coles-Lyster, described sexual assault she experienced by the team's soigneur/team assistant that happened on multiple occasions during her first time racing in Europe in 2017.

Erickson says that sexual abuse cases reported to USA Cycling are immediately reported to the US Center for SafeSport, who has exclusive authority to respond to reports of allegations of sexual abuse and sexual misconduct within the United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee and their recognized National Governing Bodies. The Center was established in 2017 and soon after became federally-authorized under the Protecting Young Victims from Sexual Abuse and Safe Sport Authorization Act of 2017.

"I think that's huge in that we aren't just putting policies in place, but we're putting in systems that can uphold those policies, and they are reviewed regularly," Erickson said.

Erickson believes that more and more athletes are speaking out against abuses in cycling because they are becoming educated about the different types of abuse, what they look like and how to recognise it if they witness it happen to a teammate or if it happens to themselves.

Athletes are also becoming more aware of their rights, codes of conduct and reporting channels, and feel empowered to speak out against abuse to make a change for future athletes. They are also seeing action being taken by organisations in response to abuse reports, which is critical.

"The biggest change is that athletes are starting to have the confidence, ability and reason to speak out," Erickson said. "We are hearing a lot more about this, even in just the last year that has prompted many people to come out and say, 'Here's stuff that we experienced as well.' A big thing is that athletes have recognised that they have power and that their voices matter, and thankfully the organisations around them are starting to be held accountable to take action when they hear those stories."

Progress in this space is happening, but there are still gaping holes within the system, and one of the major problems is that there isn't one international governing body that covers SafeSport. Athletes have to navigate the various SafeSport-like rules in each country. For a global sport like cycling, it can be challenging to stay on top of the abuse reporting channels, regulations and policies around the world.

In that sense, monitoring abuses in sport has also significantly lagged behind the fight against anti-doping. WADA was created in 1999 to promote, coordinate and monitor the fight against drugs in sports across international borders. Its World Anti-doping Code has been adopted by more than 600 sports organizations and has given the anti-doping movement consistency and continuity across sports and countries. Outside of the UCI Ethics Commission, SafeSport-like programming is all over the map.

"There isn't something like WADA, an international body designed to provide consistency across national borders for SafeSport," Erickson said. "I hope there becomes one and that we follow the same example the anti-doping community did when we begin to create an international SafeSport organisation to implement the same rules and policies across national borders.

"The conversations are happening internationally, and so I think it's a good start, but until we gain consistency across international federations, it's going to be difficult to create significant change in this space."

For now, the US Center for SafeSport is leading the way of protecting and educating athletes, sports personnel, and parents about abuse in sport, which is empowered by US Congress to design and implement misconduct-related education and policy.

It designed online education that every applicable adult in the Olympic Movement has to take every 12 months. Education covers the content of the SafeSport Code, which includes policies covering sexual misconduct, physical misconduct, emotional misconduct, bullying, hazing and harassment. The core training outlines each type of abuse, provides examples of them, and information about what to do if you suspect or know of or have been victim to any of them.

Erickson said that USA Cycling is also working on educating parents and athletes as well. The Center also provides training targeting high-school athletes and middle-school athletes; grades 3-5, 1-3 grade and kindergarten and preschool that are designed to be taken online with their parents. USA Cycling is increasingly encouraging everyone in the community to become informed and play an active role in ensuring a safe sport for all.

"There's a greater recognition and acceptance that bad things happen," Erickson said. "We are starting to get people around athletes, and the athletes, to educate themselves so that they can recognise red flags and know where to go with that information. That's a space where we still have a lot of work to do, empowering anyone and everyone involved in the sport, no matter how periphery or immediately involved they are, to be advocates and allies in this space.

"Everyone has an obligation and an opportunity to be on the lookout and be alert to red flags and know who to go to if and when they have suspicions. They don't have to have all the evidence or to do the investigations themselves. If something seems off, report it. Embrace the opportunity to be an advocate for positive change in sport."

Kirsten Frattini is the Deputy Editor of Cyclingnews, overseeing the global racing content plan.

Kirsten has a background in Kinesiology and Health Science. She has been involved in cycling from the community and grassroots level to professional cycling's biggest races, reporting on the WorldTour, Spring Classics, Tours de France, World Championships and Olympic Games.

She began her sports journalism career with Cyclingnews as a North American Correspondent in 2006. In 2018, Kirsten became Women's Editor – overseeing the content strategy, race coverage and growth of women's professional cycling – before becoming Deputy Editor in 2023.