Beating the cheaters

Anti-doping labs search for test for EPO masking agent

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Recent news reports reveal that scientists from the Lausanne anti-doping laboratory think they've detected attempts by athletes to mask the presence of the blood-boosting drug erythropoietin (EPO). They hypothesize that a protease enzyme was introduced into the urine while the athlete was giving the sample to destroy traces of the drug. Is this possible, and can the scientists develop a test to detect this method? Laura Weislo reports.

When EPO was introduced as a therapeutic agent for anemia in the late 1980's, it was a miracle drug for many patients suffering from chronic renal failure or those in chemotherapy. But the drug's darker side, the abuse by endurance athletes to boost the oxygen-carrying capacity of their blood, has led to many sporting scandals in recent years.

EPO is so effective at improving performance that athletes have continued to risk scandal, sanctions or even death to gain its benefits. The introduction of an EPO urine test in 2001 should have reduced the prevalence of the abuse of the drug, but methods for avoiding positive tests have always stayed ahead of the anti-doping laboratories.

When the test was first introduced, it could only detect EPO within a few days of its administration. Since the drug's effects are strongest several weeks after the dose, the drug was used well in advance of races where the athletes would be subjected to anti-doping controls, and undetectable by that time.

As the test was made more sensitive, athletes switched from using the normal therapeutic doses to "micro-dosing." Using this method, the drug is only detectable within a day of its use. But as the test continues to be refined, several high-profile EPO positives may be inspiring athletes to find new ways to continue to use the drug without being caught.

Scientists in Switzerland suspect that the latest method to elude the test involves the use of a powder that destroys all traces of EPO, natural or synthetic. Martial Saugy, head of the Swiss anti-doping laboratory said, "There has been a significant increase in the number of samples in which there is no EPO detected at all, leading us to believe they are being manipulated. We have no proof so far, but there are indications that a powder exists."

Matthias Kamber, of the Swiss Federal sports office, was reportedly the first to detect the problem, and helped put forth the theory that the powder was a protease, an enzyme that destroys other proteins. "It's possible that the absence of EPO in the probes have a natural cause, but it also feeds the suspicion of manipulation."

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Proteases are widely available as stain removers, meat tenderisers, or dietary supplements, and would be needed only in small amounts to destroy all of the protein in a urine sample. It has been speculated that riders put a bit on their fingers and then urinated across the powder to add it to their sample. The use of such a product seems fairly obvious, so why hasn't this been detected before?

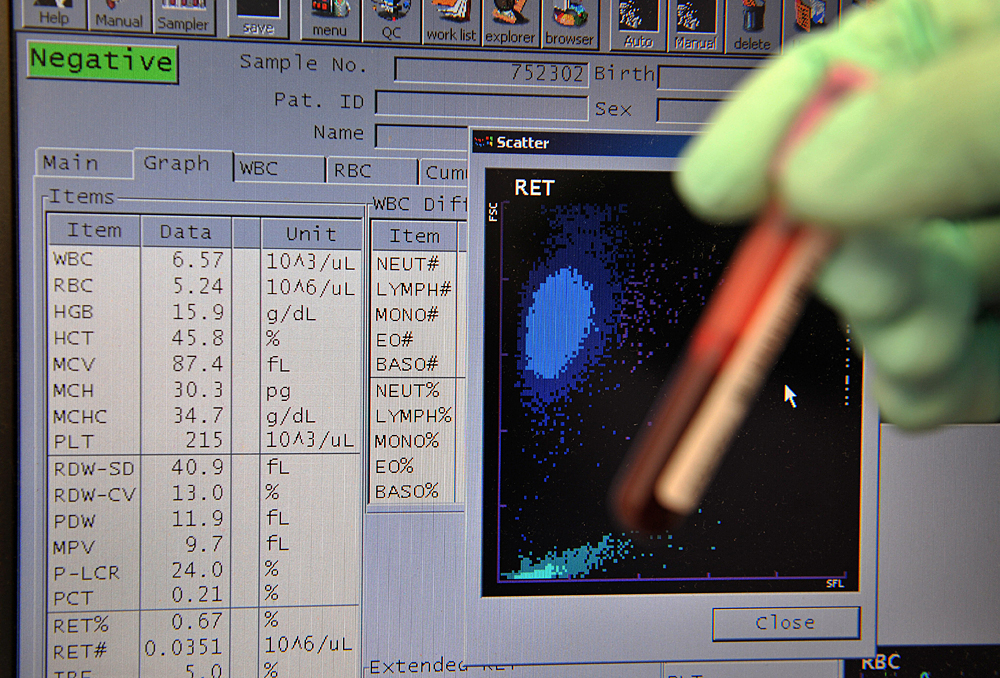

Dr. Don Catlin, director of the UCLA Olympic Analytical Laboratory in Los Angeles, California, tells Cyclingnews that they've been on the lookout for proteases in urine samples since 2002. His lab, like the Swiss lab, has seen a number of samples since 2002 that have no detectable EPO. But Catlin says, "It is not a total absence of proteins," indicating that whatever the masking agent is, it is more specific than the proteases that exist in products such as stain removers, as these enzymes would break down all the proteins in a sample.

Both the UCLA and Swiss laboratories say that the search for the protease is not simple because the enzyme breaks down very quickly, making detection difficult. Until the scientists can come up with a way to definitively identify the masking agent if it exists, it is unlikely that riders can be sanctioned as a result of a blank EPO test. There are some medical conditions that can result in the lack of EPO production naturally, so it is possible that the blank results are not the result of an attempt to cheat the test. A blank test can also be the result of a lab error, so prosecution of an athlete over a blank test would be difficult.

So the race is on to come up with a test to detect this suspected method of cheating the EPO test. USADA lawyer Travis Tygart said that the agency is "aware of the efforts [of the laboratories]" and that under the WADA code, "masking agents are prohibited," indicating that once a method of detecting the substance is developed, the anti-doping authorities will have legal recourse to sanction riders based on a masking agent-positive result. Until then, one strategy for anti-doping efforts is to simply reduce the opportunity for athletes to get the substance into their urine. Tygart says, "USADA already requires athletes to wash their hands" before giving their urine samples.

Laura Weislo has been with Cyclingnews since 2006 after making a switch from a career in science. As Managing Editor, she coordinates coverage for North American events and global news. As former elite-level road racer who dabbled in cyclo-cross and track, Laura has a passion for all three disciplines. When not working she likes to go camping and explore lesser traveled roads, paths and gravel tracks. Laura specialises in covering doping, anti-doping, UCI governance and performing data analysis.