American invasion of the Tour de France

So, when Team 7-Eleven toed the line at the start of the 1986 Tour, its impact was a total unknown...

Tales from the peloton, July 13, 2008

With Americans winning 10 of the last 21 editions of the Tour de France, it is a bit hard to believe that 1986 marked the first year an American team participated in cycling's greatest race. Coincidently, 1986 also marked the first overall win by an American; Greg Lemond rode for the highly successful La Vie Claire team composed mostly of French riders including five-time Tour winner Bernard Hinault. In fact, at that time, American riders had only been making an impact on the European pro peloton for a handful of years - largely due to Lemond. Bruce Hildebrand takes a look at the participation of the first American team in the Tour de France.

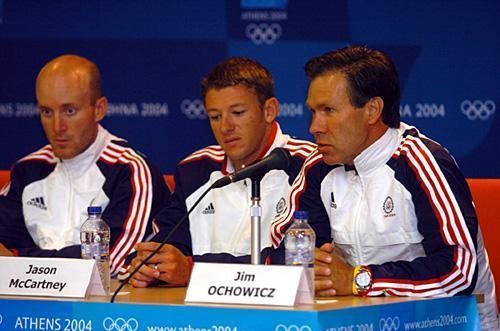

So, when Team 7-Eleven toed the line at the start of the 1986 Tour, its impact was a total unknown and many fans and teams questioned their invitation. Just as was the case this year, back in 1986, the Tour organizers personally selected every team for the race. The UCI was just a sanctioning organization and had virtually no input into the decision on who should race. Team Director Jim "Och" Ochowicz had several meetings with the Tour bosses and the crafty "Och" somehow convinced the organization that his boys could ride.

But just getting to the starting line proved difficult for team. Early that spring, President Ronald Reagan launched a pre-emptive air strike against Libya hoping to cripple a potential nuclear threat. Fearing reprisals if they came to the continent, Team 7-Eleven canceled their entire European spring racing campaign including the distinction of being the first American team to ride the Vuelta a España, which was held in April back then.

The team had to look for the most difficult races in the States, and even those events failed to produce adequate preparation for the 100+ mile day-after-day efforts demanded by the Tour. So, the men in green, red and white hatched a plan to ride 25-30 miles to their US races and then ride back the same distance thereby adding 50-60 miles/day to their efforts.

Selecting a team was a bit easier than getting in racing miles. Team 7-Eleven was heads and shoulders the best team in America and in its stable of riders included most of America's most talented racers. The team had ridden the Giro d'Italia the previous year so Och had a pretty good idea of who could survive three weeks in the saddle. Gone was Andy Hampsten, the team's best bet for a good overall finish, who had signed a short-term contract with the team for the 1985 Giro, but had ended up on Lemond's and Hinault's La Vie Claire team as a super-domestique for the mountains where he excelled.

Ron Kiefel and Davis Phinney, two members of the team since it was an all-amateur affair, were obvious choices. Davis was America's fastest sprinter who could hopefully light it up with the Eurppeans. Kiefel was the consummate all-arounder who could ride tempo on the front all day long, but was also dangerous in a sprint involving a small group.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Alexi Grewal was the 1984 Olympic gold medalist in the road race and had spent a season on the Dutch Panasonic team the year before. Doug Shapiro had won the 1984 Coors Classic, turned pro the following year for the Dutch Kwantum team and after Jonathan Boyer and Greg Lemond had become the third American to ride the Tour finishing a respectable 74th in 1985.

Eric Heiden was a five-time Olympic gold medalist in speed skating from the 1980 winter Olympics and the first ever US Professional Champion winning the inaugural Philly race in 1985. Eric had deferred entry to Stanford Medical School to take a shot at riding the Tour. This was his cycling swan song. Chris Carmichael, who would go on to coach a seven-time Tour winner, was from the flatlands of Florida, but had shown promise in the mountains as well and was a worthy addition to the team.

Bob Roll was not exactly an unknown commodity. His journeyman career with a host of teams wasn't exactly the optimal resume for the Tour, but his scrappy attitude and ability to tackle any task given to him the team director Och would hopefully pay dividends in France. Canadian Alex Steida, a cagey competitor, was capable of winning races in North American on both the road and the track.

Jeff Pierce was a climber with very few equals in the States. He had shown well against the vaunted Colombians in the Coors Classic and could hopefully be at the front in the mountains of the Tour as well. Little was known of the diminutive Mexican Raul Alcala. Och and Director Sportif, Mike Neel, had seen him at races such as the Tour of Baja, and they were hoping that he could be also effective in a three week race.

The previous year at the Giro, Team 7-Eleven's goals had been modest: one stage win and a top 20 in the overall classification. As it turned out, they won two stages, one by Keifel, the other by Hampsten and Andy also finished 20th overall. The team's goals were similar to the Giro the year before, at least a stage win and a high overall placing, but given the lack of bonafide European experience, just making it to Paris in one piece seemed to be a reasonable outcome.

The rise and fall of Steida in yelllow

The prologue start proved uneventful for the Americans. Several riders finished in the top 30, but there was nothing to raise anyone's eyeballs. That all changed the following day on stage one when Steida embarked on what appeared to be a suicide move by a rider who's day in the sun would be measured in minutes if not seconds. But Och and Mike Neel had a huge trick up their sleeve. With enough time bonuses taken en route and with Steida only 12 seconds behind the yellow jersey of Thierry Marie, Steida could claim, with a well-orchestrated breakaway, enough precious seconds to lead the race, even if he didn't win the stage!

That's exactly what happened. The Candian won every time bonus sprint then gritted his teeth to finish with the leaders and the yellow jersey read Team 7-Eleven! Europeans were in shock that the maillot jaune had fallen on a foreigner's shoulders and with such a cheeky move. Steida became the first North American to ever wear the yellow jersey, and he stayed out long enough during his attack to take the sprint and mountain jerseys as well.

It would have been a monumental day for Team 7-Eleven if not for the fact that there were two stages on the day and the afternoon's team time trial proved that Cinderella stories don't always end up with marriage to a handsome prince. Maybe it was the pressure of being the team with the yellow jersey or just plain inexperience, but not only did the team crash hard after misjudging a downhill left hand turn, they also dropped the yellow-clad Steida and came within a hair's breath of eliminating their own rider.

To be sure, back then the rules for how the Team Time Trial was scored resembled the plans for the A-bomb and several other teams almost eliminated several of their riders as well because they were unable to decipher the complex timing formula. What was painfully clear was that Steida was totally cooked from his audacious solo that morning and it was all he could do to drag his corpse to the finish. By the end of the stage and a very long day, Steida was still in the race, but the yellow jersey was no longer sitting on his shoulders.

Phinney captures first American road stage win

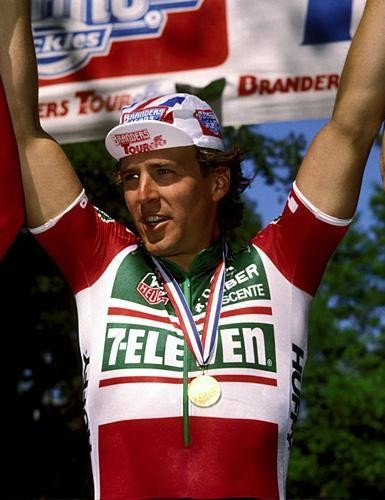

The embarrassment suffered by Team 7-Eleven's meltdown in the team time trial was all but forgotten the next day when Davis Phinney got in a small breakway and won the sprint to record the first ever road stage win by an American. Probably the most surprised rider in the whole peloton was Phinney who thought his group had failed to catch a solo rider ahead of them and the sprint he had won was the consolation prize for second place.

Actually, there were two Americans on the podium stage that day. Steida still held the lead in the king of the mountains competition, and with a few more flat stages until the Pyrenees, he was guaranteed several more days of kisses, bouquets of flowers and polka-dot jerseys.

Unfortunately, all the excitement and successes of the team in the first few days were to be the high water mark for the American team. When the race hit the first mountains in Pyrenees, both Shapiro and Carmichael, weakened by a stomach virus, dropped out. Alexi Grewal shone brightly on the tough stage to Superbagneres, but his spitting on a CBS TV camera is the memory most American fans have of the fiery rider's efforts.

On the last mountain stage and with Paris in sight, Eric Heiden crashed on the descent of the Col du Galibier and was forced to retire. By that time, the team was all but invisible in the peloton, hanging on each day hoping to survive just to start the next stage. But, while it might sound like these guys didn't deserve to be racing in France in July, nothing could be farther from the truth. Just like Team Slipstream at the 2008 Giro, Och, Neel and their riders played the cards they had to almost perfection and got maximum results from their efforts.

Roll (63rd), Pierce (80th), Kiefel (96th), Alcala (114th) and Steida (120th) all made it to the Champs Elysees and their lap of honor was both well-deserved and well-received. The "American Invasion" had been a qualified success. With an American rider winning and an American team participating, all that remained was for the two to come together and bring a yellow jersey back to the States. Lance Armstrong and his US Postal squad would do just that thirteen years later, standing on the shoulders of Phinney, Kiefel, Roll, etc.